The Trial

Except when a case settles or is dismissed, everything culminates in the trial. A successful trial outcome requires that each phase of the trial be carefully executed. One of the most important phases involves the presentation of expert testimony.

Fees

Fees associated with an expert’s trial appearance have already been reviewed in detail. Most experts establish court appearance rates on a flat fee basis for either a half- or full-day appearance. Some experts charge hourly fees consistent with the schedule established for deposition testimony. In addition to time spent in court, and regardless of what the court appearance fee arrangement is, fees associated with trial preparation (including document review and conferences with retaining counsel) are typically charged on an hourly basis.

Pretrial Preparation

It bears repeating that success as an expert requires adequate preparation. A quality expert report and strong deposition testimony are both based in large part on sufficient preparation. A successful trial presentation is no exception and, in fact, depends largely on the degree to which you prepare. In the long run, finesse and style will take you just so far as a trial witness. Whether a jury accepts your opinion depends on how well you articulate it, support it, and defend it. To do those things, you must master the facts, issues, and arguments. You must be prepared for the attacks on your position that will be made during cross-examination, often by a skilled, experienced lawyer who is being assisted by his or her own expert. Without preparation, you stand little chance of succeeding at trial.

Preparation requires a willingness to devote significant time to rereading the relevant materials supplied to you when you rendered your initial opinion. It requires that you read or reread all relevant documents supplied to you after you furnished your initial opinion, including written discovery such as interrogatory answers and the deposition testimony of party and nonparty witnesses. You must also read the reports and deposition testimony of all other experts. If professional journals or textbook excerpts have been identified, reread them and generally know their content. Make certain that you know the factual details of the case, and be ready to discuss them in court. Should your preparation be lacking in this regard, you will likely falter, as will the defense you were retained to bolster.

If you have authored reports, reread them. If you have been deposed, reread the transcript of your deposition. If an opinion you have offered is not supported by newly discovered facts, alert retaining counsel and discuss the manner in which the potential adverse impact of these facts can be softened.

The failure to adequately prepare for trial is best exemplified by the less-than-compelling testimony offered by a plaintiff’s expert at a dental malpractice trial. During cross-examination, defense counsel asked some rather basic questions about the defendant’s office radiographs, which defense counsel knew the plaintiff’s expert had reviewed at his deposition. For some unexplained reason, the witness insisted that he had never examined the films, even though his deposition transcript unequivocally indicated otherwise. Had the plaintiff’s expert adequately reviewed the relevant documents prior to his court appearance, he would not have debated his previous access to and review of the films. As a result of the expert’s refusal to acknowledge that review, his credibility was impaired.

As previously discussed, you should bring file materials to the trial and have them in court in an organized fashion. Not only will you benefit by being able to identify and use crucial documents in your file, but also the mere appearance of the underlying documents in an organized manner, such as in two- or three-ring binders, will impress the jury.

Pretrial and pretestimony conferences with retaining counsel are absolutely essential. Many defense attorneys prefer that experts meet with them before the trial begins. At that time, counsel generally reviews the expert’s opinions, identifies and examines key documents, discusses potential pitfalls, addresses the opinions of adverse experts, reviews areas of anticipated direct examination and cross-examination, discusses the creation and use of trial aids, and arranges the order of evidence presentation. You can expect that retaining counsel will initiate this meeting. At a minimum, the expert and counsel should speak about the case on the telephone before the trial begins.

In addition to the pretrial meeting, a pretestimony conference that can be conducted by telephone is useful. Most defense attorneys prefer this second preparation session to occur on the day or evening before the expert is scheduled to testify. By this point, the plaintiff’s case has been fully presented, including the testimony of the plaintiff’s expert or experts. The issues have been honed, and the documents used by the plaintiff at trial are now a matter of record. Counsel then can focus the expert’s attention on that which has already occurred at trial and advise him or her as to counsel’s assessment of the relative strengths and weaknesses of the plaintiff’s case. Defense counsel also is able to discuss the opinions of the plaintiff’s expert as offered in court and critique the jury’s outward reaction to those opinions. A review of specific questions counsel intends to pose at trial during direct examination and those counsel expects will be asked by adverse counsel during cross-examination often is also part of this conference.

Understanding Your Environment

To the novice expert, the courtroom usually is foreign territory. As a tangible symbol of the law, the courtroom’s trappings are largely based on tradition and are reflective of a palpable melding of custom and purpose.

Your effectiveness as an expert requires that you understand the environment in which you have been asked to perform. You must be comfortable in the courtroom, and you must appear comfortable to the jury. An expert who seems ill at ease on the witness stand will be poorly received by jurors. Even the most solid expert opinion will seem less credible and less persuasive if the person delivering the opinion is unable to comfortably function in court.

In order to achieve some degree of comfort, you must understand the physical environment and the roles of the typical trial participants. Because you likely spend most of your time in an examining, treatment, or operating room where your comfort level is high, the courtroom will present a new challenge. Even if you do a fair amount of public speaking at conferences and lecture colleagues, you still will be out of your element in court.

One recommended and highly effective way by which an inexperienced expert can combat this problem is to spend time in the courtroom before testifying. If you are not the first witness of the trial day, you should arrive at least 30 to 60 minutes early. If the trial judge permits, sit in court and watch the proceedings. Learn the behavioral tendencies of the various “players” in the trial. Appreciate the dynamics of the relationship between and among the human components of the trial— the judge (sometimes referred to as “the court”), the jury, the plaintiff’s attorney, the defense attorney, the plaintiff, the defendant, the court stenographer (except where the proceedings are tape-recorded), the court officer (or bailiff), the court clerk, and occasionally the judge’s law clerk. Watch the jurors and their reaction to trial events— attorney questions, witness answers, objections by counsel, the judge’s rulings, physical movement by attorneys and witnesses, and the use of trial aids and exhibits. If you are offered this opportunity, seize it. You will be amazed at how your anxiety level will decrease.

In some cases, the trial judge will not permit expert witnesses to sit in court and observe the testimony of other witnesses. At times, the trial judge, prompted by a request from adverse counsel, will direct that an expert witness remain outside the courtroom until the expert actually testifies. Therefore, if you plan to appear early, ask retaining counsel if you will be permitted to sit in court prior to testifying.

Trial Sequence

In addition to appreciating the physical characteristics of the courtroom and the role of each participant, you should also understand how a trial proceeds and some of the more general rules of behavior in court.

The trial generally begins with a brief statement by the judge to the group of prospective jurors about the nature of the case, the allegations, and the defenses. The attorneys are then introduced, and in some states, each attorney introduces his or her client and identifies the anticipated trial witnesses. The prospective jurors provide information about themselves in open court in response to questions posed by the judge and/or counsel. The trial judge will excuse certain individuals from service “for cause,” ie, due to personal experiences; familiarity with the parties, attorneys, or witnesses; financial hardship; medical reasons; language difficulties; vacation schedule; work requirements; or personal/family obligations. The court can excuse an infinite number of jurors “for cause.” Each of the attorneys may also excuse from service certain of the jurors. Generally, an attorney can exercise a peremptory challenge and excuse a prospective juror for an undisclosed reason consistent with prevailing law without articulating the “cause.” However, the presumption is that the juror has identified something in his or her personal background or has displayed a characteristic that the attorney believes might reasonably suggest a bias either against his client or in favor of the adverse party. Unless there are exceptional circumstances, each attorney is given a fixed number of peremptory juror challenges. Once those challenges are exhausted, counsel cannot eliminate any further prospective jurors without cause.

Typically, after jury selection and preliminary remarks or instructions by the trial judge, the substantive trial begins with an opening statement by the plaintiff’s attorney (whose seat at counsel table frequently is closest to the jury box) followed by the opening statement of the defendant’s counsel (whose seat at counsel table frequently is furthest from the jury box). If the trial involves multiple defendants, the sequence of defense opening statements often will follow the order in which the various defendants have been named in the Complaint. Witnesses and evidence will then be presented by the plaintiff’s attorney, at the conclusion of which the plaintiff will “rest.” The defense case is then presented with witnesses and other evidence. Again, if there are multiple defendants, each defendant generally presents his or her case in the same order as opening statements. Each defendant will “rest” at the conclusion of that defendant’s presentation of witnesses and evidence. In some instances, the plaintiff may present rebuttal evidence in response to unanticipated critical evidence offered by the defense.

After presentation of all evidence, a summation or closing argument will be offered by each attorney. The sequence may be the opposite of the opening statements. Opening and closing remarks by the lawyers are not evidence, and the jury is so advised by the trial judge. The court then instructs the jurors as to the law that applies to the case, called the Jury Charge. The jury is obligated during deliberations to apply the law recited by the trial judge during the Jury Charge to the facts as it finds based on the evidence. Following deliberations in the jury room (which may take minutes or days), the jury records its decision on a Jury Verdict Sheet and then returns to the courtroom to verbally announce its verdict in open court to the judge, the parties, and their counsel.

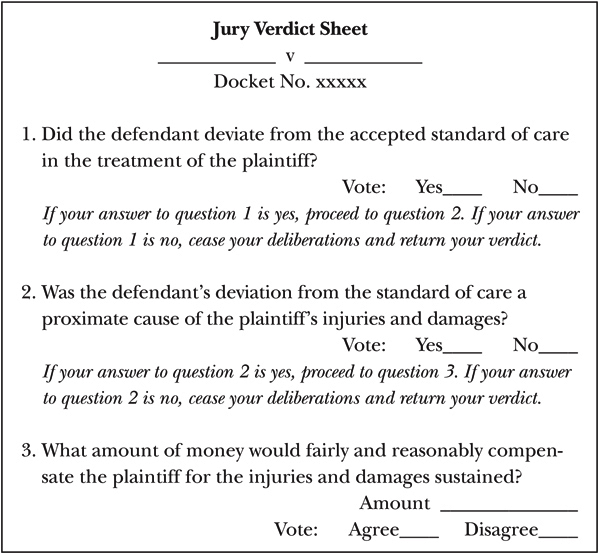

A Jury Verdict Sheet in a very basic malpractice case with issues of liability, causation, and damages may look like this sample:

Affirmative answers to both the first and second questions establish that the defendant was negligent and that such negligence was a substantial cause of the injuries and damages alleged. The jury must then decide the amount of money to which the plaintiff is entitled. A negative response to either the first or second question will result in a verdict in favor of the defendant. A positive response to the first question alone is insufficient to return a verdict for the plaintiff. In order for the defendant to be liable, the jury must determine that the defendant acted negligently and that the negligent conduct was a proximate cause of the plaintiff’s alleged injuries and damages. A proximate cause is often defined as a cause that set other causes in motion and was a substantial factor in bringing about the alleged injury. It is an event that naturally and probably led to and might have been expected to produce the alleged result.

Of course, a more complex case involving additional issues such as informed consent, aggravation of a preexisting condition, comparative negligence, or mitigation of damages, or one that includes a plaintiff’s spouse or multiple defendants, will complicate the proofs at trial and increase the number of questions on the Jury Verdict Sheet.

Upon announcement of the jury’s verdict in open court, barring any successfully argued verdict-related motions, a judgment generally is entered in favor of the prevailing party, and the trial phase is formally over. Motions may thereafter follow (often by the losing party), and an appeal may be filed. Usually, however, the end of the trial is the end of the malpractice lawsuit.

Intratrial Events

During trial, counsel will often address the court using rather formal language intended to convey a sense of respect properly due the trial judge. It is expected that counsel also will be addressed by the court with appropriate respect. Witnesses are to be treated with respect by examining counsel, and the jury is deserving of the respect of all trial participants.

When it is necessary, address the trial judge as Your Honor. Although you may invoke the more casual term Judge, use it less frequently than Your Honor. Refer to retaining and examining counsel as Mr ______ or Ms ______. Unless instructed otherwise by retaining counsel, parties should be referred to as Mr ______, Ms______, or Dr ______.

The trial judge may interrupt your response to a question at any time. If this should happen, stop talking and defer to the court and its need to comment. If your testimony is interrupted by a remark from either counsel (typically an objection), stop and allow counsel to complete his or her statement and await instruction from the court or examining counsel as to if or how you may proceed.

A typical and repeated occurrence during a trial is the sidebar conference. Over time, it serves as a source of annoyance and frustration to witnesses and jurors alike. A sidebar conference is a short meeting between the trial judge and counsel. It generally takes place alongside the judge’s bench opposite the witness stand and may be convened at the direction of the trial judge or at the request of one of the attorneys. The remarks by the trial judge and counsel are not intended for witness or jury consumption. Consequently, voices must be kept in low tones so as to minimize the possibility that a witness or a juror may overhear the discussion. A sidebar often occurs in response to an objection by one of the lawyers to a question or as a result of testimony elicited from a witness. In such instance, the topic of discussion is one that involves issues of law or evidence. Procedural or scheduling matters may also be addressed at sidebar.

Although exceptions exist, most sidebars are brief, usually lasting from 30 seconds to 5 minutes. If, after the sidebar begins, it appears to the trial judge that the conference will consume significantly more time, the court may excuse the jury from the courtroom, and the witness may be asked by the judge to temporarily leave the courtroom as well. Excusing the jurors and the witness protects them from overhearing the sidebar. Possibly prejudicial comments by counsel, which jurors and perhaps witnesses overhear, may be the basis for a mistrial and the subsequent need to start the trial process anew at a later date with a new jury.

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses