Because of its unique blood supply, the temporal area provides a tripartite system of flaps for reconstruction. Two of these, the temporoparietal (TP) fascia and temporalis flaps, are most commonly used for reconstructing defects in the head and neck because of their proximity, reliability, and adaptability. Both are described here, including their indications, anatomy, and flap-harvesting technique, along with contraindications and potential complications.

Etiopathogenesis/Causative Factors

Composite defects of the maxillofacial region requiring regional tissue transfer most commonly result from oncologic resection. The resultant defects often lead to communication between the oral, nasal, sinus, and rarely, cranial contents. In addition, avulsive traumatic injuries can result in defects too large for coverage with local advancement flaps. Finally, recalcitrant oral-antral and oral-nasal communications from previous cleft palate or dentoalveolar misadventures that have failed previous attempts at closure may require regional flaps for closure. Although obturation with a prosthesis is possible, patients are often unwilling or unable to accept management with a prosthesis. Even if prosthetic obturation is planned, flaps may be indicated. For example, flaps may be used to offer support to the globe in cases of loss of the orbital floor, to cover the bone of the orbit following orbital exenteration, or to seal off communication with the cranial vault. See further discussion later under specific indications and contraindications.

Anatomy

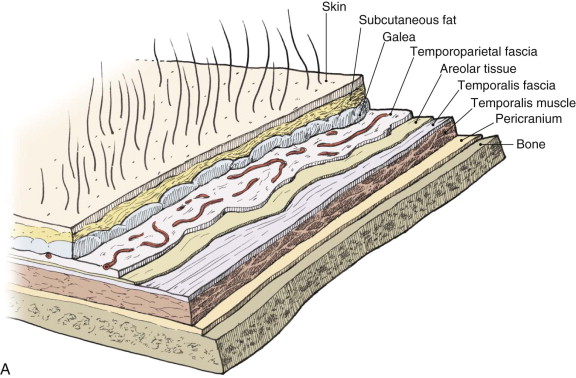

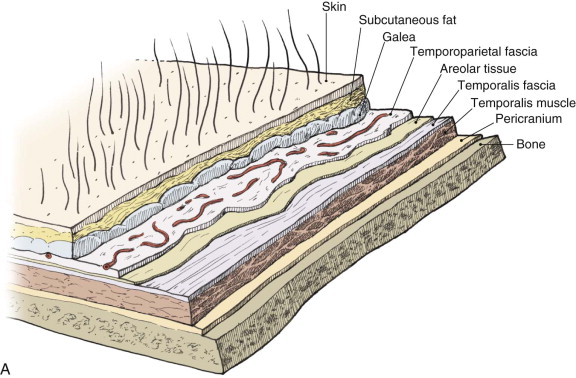

An understanding of the anatomic layers of the temporal area is critical for proper flap development. The nomenclature describing the various fascial layers in this area is often confusing because of inconsistencies in use. For example, some authors refer to the temporalis muscle fascia as the deep temporal fascia and the TP fascia as the superficial temporal fascia. For consistency, the terminology used here to describe the five layers of the scalp in the temporal area from superficial to deep include skin and subcutaneous fat, TP fascia, loose areolar tissue, temporalis muscular fascia, and temporalis muscle ( Fig. 64-1 ). Beneath the temporalis muscle lies the pericranium.

The TP fascia is the continuation of the superficial musculoaponeurotic system (SMAS) above the zygoma. Superiorly, it becomes the galea aponeurotica at the temporal line. Superficial to the TP fascia is subcutaneous tissue, which varies in thickness. In addition, above the temporal line, dense fibrous connections exist between the dermis and the TP fascia. Beneath the TP fascia is a loose areolar tissue plane that separates it from the firm, glistening temporalis muscular fascia. This areolar tissue plane is avascular and allows mobility of the scalp over the deeper layers.

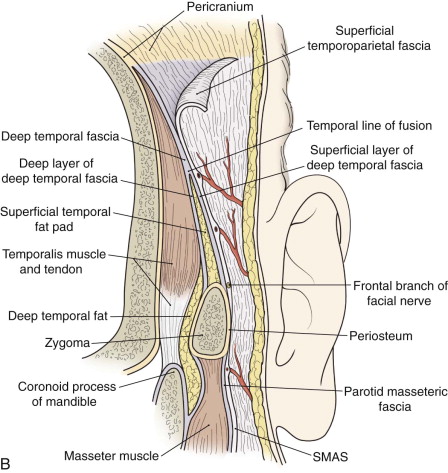

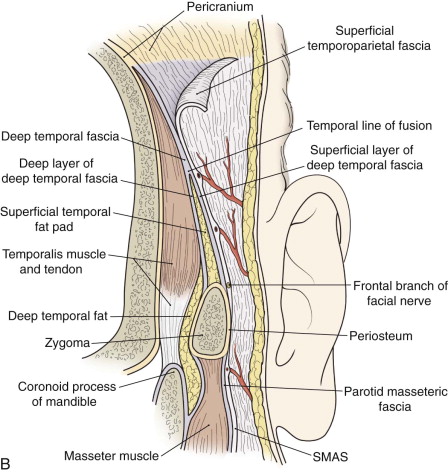

The temporalis fascia attaches superiorly along the superior temporal line and covers the temporalis muscle. Approximately 2 cm above the zygomatic arch at the line of fusion the temporalis muscle fascia divides into the superficial layer of the temporal fascia and the deep layer of the temporalis fascia, between which lies the temporal fat pad. Inferiorly, the deep layer of the temporalis fascia blends with the periosteum of the zygomatic arch and extends inferiorly as the fascia overlying the masseter muscle. The temporalis fascia fuses to the pericranium above the temporal line.

Of critical importance to raising of flaps in the temporal region is the relationship of the facial nerve, specifically the frontal branches, which are at risk during flap development and inset. The frontal branch courses on the undersurface of the TP fascia approximately 1.5 cm lateral to the orbital rim. It crosses the zygomatic arch an average of 2 cm (range, 0.8 to 3.5 cm) anterior to the external auditory canal.

The vascular pedicle of the TP fascia flap is the superficial temporal artery arising from the external carotid system and the associated superficial temporal vein. The TP fascia also receives contributions from the occipital, postauricular, supraorbital, and supratrochlear vessels via multiple anastomotic connections. Division of these vessels during development of the flap, however, does not compromise it. The superficial temporal artery tends to run within the fascia, whereas the vein usually lies more superficially on the outer surface of the fascia and posterior to the artery. The artery typically divides into anterior and posterior branches approximately 3 cm above the tragus or 1 cm above the superior helix. The auriculotemporal nerve lies posterior to the vessels and is usually easily preserved during flap harvest.

The temporalis fascia is supplied primarily by the middle temporal artery, which branches from the superficial temporal artery just superior to the zygomatic arch. Preservation of this branch allows the development of a separate layer of fascia. This attribute is most commonly exploited along with the TP fascial flap to sandwich cartilage grafts.

The temporalis muscle is supplied by two dominant pedicles, the anterior and posterior deep temporal arteries, which arise from the internal maxillary artery and their associated veins. In addition, the most posterior aspect of the muscle receives its blood supply from the middle temporal artery. The two dominant pedicles allow development of a bilobed flap. Because of the small contribution of the middle temporal artery to the posterior aspect of the muscle, the muscle is generally divided in a one-third anterior and two-thirds posterior design. This allows the posterior limb to be supplied by the posterior temporal artery. The anterior and posterior temporal arteries enter on the deep, inferior surface and course between the muscle and periosteum, thus making their preservation easier when approached from a superior direction (see the later discussion on surgical technique). Though superficial to the periosteum, from a practical standpoint the vessels are intimate with the bone and may actually groove it. For this reason it is critical to raise the muscle from the bone in a subperiosteal plane.

Anatomy

An understanding of the anatomic layers of the temporal area is critical for proper flap development. The nomenclature describing the various fascial layers in this area is often confusing because of inconsistencies in use. For example, some authors refer to the temporalis muscle fascia as the deep temporal fascia and the TP fascia as the superficial temporal fascia. For consistency, the terminology used here to describe the five layers of the scalp in the temporal area from superficial to deep include skin and subcutaneous fat, TP fascia, loose areolar tissue, temporalis muscular fascia, and temporalis muscle ( Fig. 64-1 ). Beneath the temporalis muscle lies the pericranium.

The TP fascia is the continuation of the superficial musculoaponeurotic system (SMAS) above the zygoma. Superiorly, it becomes the galea aponeurotica at the temporal line. Superficial to the TP fascia is subcutaneous tissue, which varies in thickness. In addition, above the temporal line, dense fibrous connections exist between the dermis and the TP fascia. Beneath the TP fascia is a loose areolar tissue plane that separates it from the firm, glistening temporalis muscular fascia. This areolar tissue plane is avascular and allows mobility of the scalp over the deeper layers.

The temporalis fascia attaches superiorly along the superior temporal line and covers the temporalis muscle. Approximately 2 cm above the zygomatic arch at the line of fusion the temporalis muscle fascia divides into the superficial layer of the temporal fascia and the deep layer of the temporalis fascia, between which lies the temporal fat pad. Inferiorly, the deep layer of the temporalis fascia blends with the periosteum of the zygomatic arch and extends inferiorly as the fascia overlying the masseter muscle. The temporalis fascia fuses to the pericranium above the temporal line.

Of critical importance to raising of flaps in the temporal region is the relationship of the facial nerve, specifically the frontal branches, which are at risk during flap development and inset. The frontal branch courses on the undersurface of the TP fascia approximately 1.5 cm lateral to the orbital rim. It crosses the zygomatic arch an average of 2 cm (range, 0.8 to 3.5 cm) anterior to the external auditory canal.

The vascular pedicle of the TP fascia flap is the superficial temporal artery arising from the external carotid system and the associated superficial temporal vein. The TP fascia also receives contributions from the occipital, postauricular, supraorbital, and supratrochlear vessels via multiple anastomotic connections. Division of these vessels during development of the flap, however, does not compromise it. The superficial temporal artery tends to run within the fascia, whereas the vein usually lies more superficially on the outer surface of the fascia and posterior to the artery. The artery typically divides into anterior and posterior branches approximately 3 cm above the tragus or 1 cm above the superior helix. The auriculotemporal nerve lies posterior to the vessels and is usually easily preserved during flap harvest.

The temporalis fascia is supplied primarily by the middle temporal artery, which branches from the superficial temporal artery just superior to the zygomatic arch. Preservation of this branch allows the development of a separate layer of fascia. This attribute is most commonly exploited along with the TP fascial flap to sandwich cartilage grafts.

The temporalis muscle is supplied by two dominant pedicles, the anterior and posterior deep temporal arteries, which arise from the internal maxillary artery and their associated veins. In addition, the most posterior aspect of the muscle receives its blood supply from the middle temporal artery. The two dominant pedicles allow development of a bilobed flap. Because of the small contribution of the middle temporal artery to the posterior aspect of the muscle, the muscle is generally divided in a one-third anterior and two-thirds posterior design. This allows the posterior limb to be supplied by the posterior temporal artery. The anterior and posterior temporal arteries enter on the deep, inferior surface and course between the muscle and periosteum, thus making their preservation easier when approached from a superior direction (see the later discussion on surgical technique). Though superficial to the periosteum, from a practical standpoint the vessels are intimate with the bone and may actually groove it. For this reason it is critical to raise the muscle from the bone in a subperiosteal plane.

Diagnostic Studies

Temporoparietal Fascia Flap

When considering the TP fascia flap, inspection of the temporal area should be undertaken with attention paid to previous surgical scars in the area that may have interrupted the superficial temporal vessels. A familial history or clinical findings consistent with male pattern baldness should be noted because it is a relative contraindication to use of the TP flap (see later). Doppler can be used to outline the course of the superficial temporal artery preoperatively.

Temporalis Flap

Likewise, when a temporalis flap is considered, the area should be examined for evidence of previous surgery. Since the blood supply to the muscle enters on its deep surface, it is unlikely that it has been compromised unless the patient has previously undergone surgical approaches to the infratemporal fossa or lateral skull base approaches. Evidence of temporal wasting can be a clue to a compromised temporalis. In addition, having patients clench their teeth preoperatively can give some idea regarding the size of the muscle and its viability.

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses