Large maxillofacial defects secondary to trauma or cancer ablation frequently pose a challenge for the reconstructive surgeon. These defects often cannot be closed without excessive tension and obliteration of normal anatomy. Various surgical methods have been developed to restore soft tissue bulk and recreate form and function. One of the earliest methods described involved development of the pectoralis major (PM) myocutaneous flap, which was first used by Dr. Stephan Ariyan in the late 1970s for reconstruction of ablative surgical defects in patients with head and neck cancer. Since then, it has been extensively used in the context of head and neck reconstructive surgery to reliably repair large soft tissue deficits associated with continuity defects in the mandible, floor of the mouth, and related orofacial structures. The design of this axial-pattern flap is versatile in that it can be used to provide coverage of both mucosal and cutaneous defects simultaneously. The flap provides protection for neurovascular structures in the neck and reinforces tissue with compromised vascularity or at increased risk for dehiscence and breakdown (e.g., irradiated tissue, diabetic patients). A variation of the flap, the myofascial flap, lacks the associated skin paddle and can be used to effectively close smaller mucosal defects and provide soft tissue bulk.

With recent advances in microvascular surgery, free flap procedures have assumed a more dominant role in the reconstruction of head and neck defects. Free fibula grafts are now used frequently for the reconstruction of large mandibular continuity defects. However, these procedures require great expertise and extensive time to perform, whereas the PM flap is easy to develop and can be performed quickly. One of the many variants of the originally described PM myocutaneous flap incorporates an osseous component (e.g., rib) that remains pedicled to the flap. Thus, more than 30 years after its inception, the PM flap continues to be a robust, versatile flap design used extensively in head and neck reconstructive surgery.

Treatment/Reconstructive Goals

Indications

The PM myocutaneous flap should be considered in any patient with a soft tissue defect involving the oral cavity or associated cutaneous structures. This flap is ideally used to reconstruct defects involving the mandible, floor of the mouth, upper part of the neck, and lower third of the face. The flap also provides undamaged, well-vascularized tissue for defects secondary to osteoradionecrosis. For surgeons who perform non-vascularized secondary bone grafts, the flap provides a generous soft tissue envelope. Advantages of the PM flap are numerous. They include the capability of customizing the skin paddle to the size of the defect, a reliable vascular supply, the ability to easily close the donor site, and technical ease in elevating the flap. While evaluating the patient, it is important to assess the extent of the defect and determine the amount of mucosal or cutaneous soft tissue coverage needed. Whether this is a viable option is dependent on a number of factors, including the patient’s anatomy and flap design and inset. In general, the superior “absolute” limits for flap rotation extraorally and intraorally are the zygomatic arch and the superior aspect of the tonsillar pillar, respectively. If a smaller defect is anticipated, a myofascial flap may be used without the associated skin paddle.

Contraindications

There are relatively few contraindications to reconstruction with the PM flap. That being said, the reconstructive surgeon must consider the following situations. If the dimension of the defect is too large or the defect extends outside the reach of the flap, other techniques for reconstruction should be considered. This technique should also be used with caution in patients who have previously sustained trauma to the chest wall or undergone chest surgery (e.g., mastectomy, implants, pacemakers, compromising scars, burns, previous subclavian puncture, or MEDport use) because the anatomy of the approach to the PM is likely to be altered and the muscle itself may have a compromised vascular supply and exhibit fibrosis and contracture. In patients with the Poland anomaly, a congenital condition with an incidence of 1 in 10,000 to 100,000, this procedure is an absolute contraindication since the PM muscle is underdeveloped or absent.

Preoperative Considerations

Rotation of the flap from the chest to the orofacial defect will result in an asymmetric chest deformity and, in females, breast asymmetry and may cause excessive bulking at the site of the defect and the ipsilateral neck. Use of this flap will inherently weaken the patent’s shoulder and arm on the ipsilateral side, thereby potentially resulting in disability during the postoperative period, although this is normally well tolerated in most patients. As with many surgical procedures in this region, use of the PM flap carries with it a risk for infection, hematoma formation, seroma formation, hemothorax, and pneumothorax. Other disadvantages inherent in using the PM flap for reconstruction include skin color mismatch at the recipient site, limited range of rotation when used for maxillary defects, hair growth when the flap is placed intraorally because the adnexal structures in the skin are left intact, and altered external chest morphology and breast asymmetry in females. If the patient experiences complications in the postoperative period, extensive wound care may be necessary. Furthermore, additional surgical procedures may be necessary to salvage the flap or to provide adequate wound closure.

Preoperative Considerations

Rotation of the flap from the chest to the orofacial defect will result in an asymmetric chest deformity and, in females, breast asymmetry and may cause excessive bulking at the site of the defect and the ipsilateral neck. Use of this flap will inherently weaken the patent’s shoulder and arm on the ipsilateral side, thereby potentially resulting in disability during the postoperative period, although this is normally well tolerated in most patients. As with many surgical procedures in this region, use of the PM flap carries with it a risk for infection, hematoma formation, seroma formation, hemothorax, and pneumothorax. Other disadvantages inherent in using the PM flap for reconstruction include skin color mismatch at the recipient site, limited range of rotation when used for maxillary defects, hair growth when the flap is placed intraorally because the adnexal structures in the skin are left intact, and altered external chest morphology and breast asymmetry in females. If the patient experiences complications in the postoperative period, extensive wound care may be necessary. Furthermore, additional surgical procedures may be necessary to salvage the flap or to provide adequate wound closure.

Surgical Anatomy

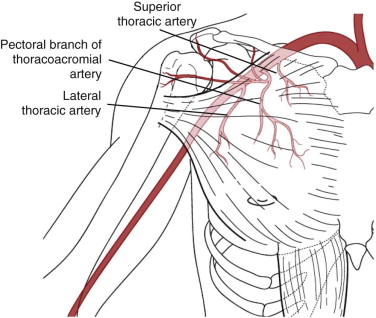

The fan-shaped PM muscle is situated deep to the subcutaneous connective tissue in the anterior chest wall ( Fig. 68-1 ). In female patients, the breast and associated glandular tissue overlie the majority of the muscle. The muscle itself has two heads, the clavicular and sternocostal. These heads are recognized as the origins of the PM muscle. The clavicular head attaches superomedially to the medial half of the anterior aspect of the clavicle. The sternocostal head attaches inferomedially to the anterior surface of the sternum and the superior aspect of the costal cartilages of the first six ribs. Inferiorly, the muscle originates from the aponeurosis of the external oblique muscle. In addition, the pectoralis muscle fascia inferiorly is confluent with the rectus abdominis muscle fascia. Superolaterally, the PM muscle inserts onto the head of the proximal end of the humerus at the intertubercular groove. The PM muscle is a major structural component of the anterior wall of the axilla and contributes to the formation of the anterior axillary fold. The summative action of the two heads of the PM muscle is to adduct and medially rotate the humerus. Once the muscle flap has been elevated, arm function is typically compensated by the latissimus dorsi muscle. Deep to the PM muscle are the pectoralis minor muscle, the subclavius muscle, the serratus anterior muscle, and the intercostal muscles. The PM muscle is surrounded by a layer of fascia, which facilitates dissection.

Vascular Supply of the Pectoralis Major

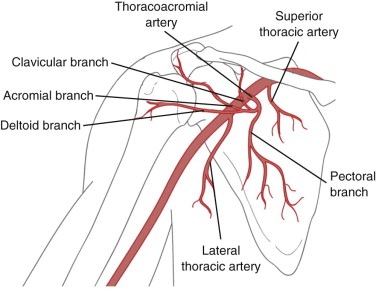

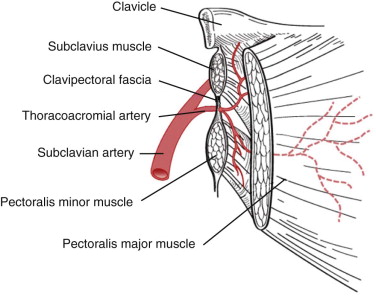

The pectoral branch of the thoracoacromial artery provides the main vascular supply to the PM muscle once elevated (see Fig. 68-1 ). The pectoral branch of the artery courses obliquely and parallel to a line between the acromion process and xiphoid process. The thoracoacromial artery is the first branch of the axillary artery. It arises from the axillary artery deep to the clavicle. The pectoral branch of the thoracoacromial artery is one of four main branches (the others include the deltoid, acromial, and clavicular branches) ( Fig. 68-2 ). As the thoracoacromial artery branches off the axillary artery, it penetrates the clavipectoral fascia ( Fig. 68-3 ) and courses deep to the pectoralis muscle, at which point it enters the muscle from its deep surface and branches intramuscularly (see Fig. 68-2 ). Vascular supply to the elevated PM muscle flap is also provided by the lateral thoracic artery, albeit to a lesser extent. Maintenance of the integrity of this vessel improves viability. The superior thoracic artery also contributes a negligible amount. The aforementioned arteries are accompanied by their venae comitantes.

Parasternal perforators from the internal mammary artery provide vascularity to the medial aspect of the PM muscle while the muscle is in situ. During elevation of the flap, these vessels are often transected. However, care should be taken to maintain the integrity of the first and second perforators because they supply the skin used in the deltopectoral flap. Maintenance of this blood supply is important should a salvage procedure be required, although the deltopectoral flap is rarely used today.

Innervation of the Pectoralis Major

Both the lateral and medial pectoral nerves, nerves that are branches of the brachial plexus, provide motor innervation to the PM muscle. The lateral pectoral nerve arises from the lateral cord of the brachial plexus and is composed of branches of C5, C6, and C7. It provides control of the clavicular head and cross-innervates the sternocostal head of the muscle. The medial pectoral nerve arises from the medial cord of the brachial plexus and is composed of branches of C8 and T1. A few branches transect the pectoralis minor muscle and enter the PM to provide motor control of the sternocostal head of the muscle. These nerves are transected as they are encountered in the surgical dissection. The benefit of doing so is two-fold: it improves the arc of rotation of the flap, and denervation of the flap causes the muscle to atrophy, thereby debulking the flap over time.

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses