The previous chapter emphasized pathophysiologic mechanisms leading to chronic orofacial head pain. The important role of acute trauma and repeated noxious stimuli to the oral and maxillofacial structures has been well documented as major etiologic factors that lead to chronic orofacial pain conditions. It is clear that recurrent noxious stimulation of the peripheral branches of the trigeminal nerve lead to peripheral and central sensitization of ascending nerve pathways, ultimately leading to chronic orofacial pain. Stimulation of these ascending pathways reach the cerebral cortex resulting in the patient’s awareness of pain at a site localized peripherally in the oral and maxillofacial region. A major challenge for the oral and maxillofacial surgeon as a clinician is to realize that the patient’s perception of the site and source of pain is peripheral, and the patient will frequently request localized treatment at this peripheral site. If the pain is neuropathic in origin, with central sensitization, multiple localized treatments not only will fail to alleviate the pain, but will further stimulate the ascending pathways creating more localized tissue injury, further exacerbating chronic orofacial pain.

A thorough knowledge of the principles of diagnosis, management, causation, and prevention of chronic orofacial pain is essential for every oral and maxillofacial surgeon, regardless of whether the clinician chooses to actively diagnose and treat these challenging patients or decides to refer them to other specialists. The reason for this is that the oral and maxillofacial surgeon is in a key position to prevent the progression from acute pain to a chronic pain condition. Conversely, failure to properly diagnose and manage patients who have pain may lead to multiple surgeries, failed treatments, and create the physiologic environment for progression to chronic pain.

The previous chapter reviewed the diagnosis and treatment of the major types of chronic orofacial pain conditions that have been classified as being neurologic, musculoskeletal, and vascular in origin. This chapter will focus on the most practical clinical aspects of chronic orofacial pain that every oral and maxillofacial surgeon should know regardless of whether he or she will be the primary treating clinician for the chronic pain condition or the one who refers the patient for further specialty care. The major sections of this chapter include:

- •

Principles of diagnosis and management

- •

The essential role of the oral and maxillofacial surgeon in the prevention of progression to chronic orofacial pain

- •

Diagnosis and treatment of the most common inflammatory and degenerative temporomandibular joint conditions

▪

PRINCIPLES OF DIAGNOSIS AND MANAGEMENT OF PATIENTS WITH CHRONIC OROFACIAL PAIN

THE INITIAL VISIT

Patients with chronic orofacial pain conditions have complex histories frequently including misdiagnoses, multiple dental and surgical procedures, and multiple failed treatments. The frustration of these patients and their family members is immense. The chronic pain condition often creates intense physical and emotional suffering and is frequently associated with anxiety and depression. The main point here is that the initial consultation visit requires a significant amount of time for the patient and the clinician. The patient needs time to adequately express their chief complaint(s) and recount the history. The clinician needs time to properly assimilate the extensive information presented, perform a head and neck examination, obtain appropriate diagnostic images, review previous records and diagnostic images, process the information, develop differential diagnoses, and provide treatment recommendations with proper sequencing. Additionally, there needs to be time set aside for the patient to assimilate the information provided by the clinician and ask questions. The time that is required for this initial consultation appointment will vary with different patients and clinicians. However, it is rare for the initial appointment to take less than 1 hour, and in most instances, the time allotment should be 1½ hours.

It is important for the clinician to obtain an appropriate history without excessive amounts of superfluous information from the patient. Patients who suffer from chronic orofacial pain often have extensive histories, and the anxious patient believes that it is necessary to provide the clinician every detailed piece of information in the quest for a diagnosis and successful treatment. Unfortunately, excessive amounts of superfluous information can often be counterproductive in assisting the clinician in making the correct diagnosis. Therefore, a clinician-guided interview is necessary. At the start of the interview, the clinician should lay down the ground rules of the interview and ask the patient to respond only to the question that is asked. However, the clinician must also inform the patient that after this guided interview is complete, the patient will be free to provide the clinician with any other information that he or she believes is helpful. The key components of the clinician guided history are as follows:

- 1.

Chief complaint(s) listed in order with the most severe symptoms being first

- 2.

History of present illness—in chronologic order so that a timeline of events can be constructed. The patient should provide a chronologic list of treating clinicians that includes their specialty, the diagnosis rendered, the treatment recommended, actual treatment provided, and the patient’s response to that treatment .

- 3.

Pain history 1 :

- a.

Location(s)—one finger with pointing to those spots that are most painful in descending order to those that are less severe

- b.

Duration—continuous or intermittent

- c.

Quality of the pain

- i.

Shocklike

- ii.

Aching

- iii.

Burning

- iv.

Numbing

- v.

Other descriptions

- i.

- d.

Precipitating factors (e.g., light touch, opening jaw, chewing, drinking hot or cold liquids, stress, exercise, spontaneous)

- e.

Temporal predisposition (early AM, progression throughout course of day, early evening before sleep, awakens patient from sleep)

- f.

Factors that reduce pain (effective medications, moist heat, ice, massage)

- a.

Following the completion of a careful clinician-guided history, the oral and maxillofacial surgeon will be in a better position to establish a more accurate differential diagnosis. Additionally the examination that follows this history may become more focused toward establishing the correct diagnosis.

The consultation rarely ends at the first visit because the diagnosis and therapeutic approaches will frequently change based on the response to treatment and the results of further diagnostic information as the work-up progresses. The impact of having a new chronic orofacial pain patient in the middle of a busy day in an oral and maxillofacial surgeon’s office can be quite disruptive to the schedule. Therefore, if the clinician is unable to allocate the appropriate time and energy in the management of these patients, it is often better to be prepared to refer the patient to a specialist or a group of specialists who have demonstrated expertise in the diagnosis and management of chronic pain.

Assuming the oral and maxillofacial surgeon is willing to have the responsibility of diagnosis and treatment of the chronic orofacial pain patient, then the following are some of the key principles in managing these patients:

FLEXIBLE DIAGNOSES-MANAGEMENT CONCEPT

It is common, even for the experienced clinician, to be uncertain of the diagnosis and treatment of a chronic orofacial pain patient. This is unlike the more common situation in which a patient in acute pain has an abscess that is generally easy to diagnose, treat, and cure. Because this is not the case with chronic pain patients, it is important for the clinician to have a different mindset with the development of differential diagnoses that remain flexible. The concept here is that the clinician develops an initial differential diagnoses and treats the patient according to the most likely condition(s) causing the chronic pain. Based on the response to treatment, there is a continual reevaluation of the diagnoses and treatment.

The following clinical scenario is an example of the flexible diagnoses-treatment concept in action. A hypothetical patient is referred to the oral and maxillofacial surgeon who reports having brief episodes (1 to 5 seconds) of well-localized unilateral facial pain, followed by a dull aching pain that is ipsilateral and poorly localized. The patient has some of the features of trigeminal neuralgia, but the clinical presentation is not classic. Patients who have this and similar scenarios will frequently seek a dental evaluation that either fails to reveal any dental pathologic condition or results in dental treatment that fails to alleviate the symptoms. When this hypothetical patient is referred to the oral and maxillofacial surgeon, the clinical examination is often unremarkable. In this scenario, the head and neck examination is negative except for tenderness to palpation of the muscles of mastication, particularly the masseter and temporalis. However, the history of short episodes of sharp pain suggests trigeminal neuralgia. The initial differential diagnoses would include trigeminal neuralgia and masticatory muscle spasm. After the initial evaluation, the patient may be placed on a course of anticonvulsant medication therapy (e.g., gabapentin 300 mg t.i.d. or carbamazepine 200 mg b.i.d.). At the follow-up visit, if the patient reports a significant reduction in symptoms, the primary diagnosis of trigeminal neuralgia becomes more likely. The response to treatment and the diagnosis of trigeminal neuralgia warrant further investigation with a brain MRI to rule out an intracranial tumor or lesion. If the patient had no response to the anticonvulsant medication, the clinician may proceed to increase the medication dosage or change the primary diagnosis to masticatory muscle spasm and treat the patient with muscle relaxants and physical therapy. The flexible diagnosis-treatment concept emphasizes the continual reevaluation of the diagnoses and therapeutic efficacy, with alterations in the diagnosis and treatment according to the patient’s response. The clinician must also be aware that patients frequently have multiple concomitant diagnoses that require diagnosis-specific treatment for each condition. Therefore, the example provided previously may require treatment of masticatory myospasm and trigeminal neuralgia once the primary diagnosis is established.

USE LOCAL ANESTHETIC INJECTIONS TO ENHANCE DIAGNOSTIC ACCURACY AND PROVIDE PAIN RELIEF

At the initial visit, the chronic facial pain patient who has seen multiple clinicians has often lost hope of having pain relief and is often frustrated about the failure to have an accurate diagnosis to explain the cause of their pain. They will often believe that the failure of clinicians to provide a specific diagnosis and cause for their pain means that their health care providers believe that their pain is psychogenic in origin and has no physiologic basis. Thus, the patient will often cling to the belief that the pain is coming from a specific tooth. Their hope is that removal of that specific tooth, regardless of how many other teeth have been removed or treated, will relieve them of their pain, end their suffering, and thus, disprove the psychogenic cause concept. The clinician will often be unable to detect any signs of pathologic condition on the clinical and radiographic examination. However, these patients will often have pain to percussion or palpation of a specific tooth, and the clinician may consider the diagnosis of a tooth fracture, pericementitis, or a nonspecific pulpitis. Diagnostic local anesthetic injections are extremely valuable at the time of the initial visit of the chronic orofacial pain patient for the following reasons:

- 1.

Local anesthetic injections are helpful in differentiating peripheral pain of dental or musculoskeletal cause versus central mediated pain.

- 2.

Local anesthetic injections that result in pain relief provide hope for the patient that there is something that can “turn off” or reduce the pain. Local anesthetic injections that provide pain reduction provide a significant psychological lift and further corroborates for the patient that the cause of the pain is not psychogenic, but based on excessive activity of specific neural pain pathways.

- 3.

Local anesthetic injections that successfully reduce pain provide the patient and clinician an important therapeutic adjunct by blocking the pain. This helps to reduce the repeated stimulation of central ascending nerve pathways, which contribute to exacerbation of neuropathic pain.

- 4.

The results of the local anesthetic injections provide further direction for the clinician concerning treatment.

The patient who has pain localized to a specific tooth, who responds favorably with pain reduction from a local anesthetic block or infiltration may provide the clinician further justification for local dental treatment. However, if there is a history of multiple episodes of localized tooth pain with failed dental treatments (e.g., extraction, apicoectomy, endodontic therapy), the clinician should be very cautious about drawing the conclusion that the pain is solely dental in origin. It is important for the oral and maxillofacial surgeon to realize that many central mediated pain conditions, such as trigeminal neuralgia or atypical facial neuralgia, have a peripherally located trigger zone, which when stimulated with light touch, pressure, or other sensory stimuli, can lead to a triggering of central neuropathic pain. It is not unusual for occlusal pressure on a specific tooth to be the source of a trigger of central mediated pain with local anesthetic blocks resulting in pain reduction. Therefore in the absence of objective signs of local dental pathologic conditions, the clinician should be very cautious in providing localized dental treatment in the patient with chronic facial pain, even if the patient responds favorably to local anesthetics. As discussed previously, further surgical trauma can provide additional stimulation of ascending central neural pathways, leading to a further exacerbation of chronic pain. The corollary to this is that repeated blocking of the peripheral stimulus leading to stimulation of ascending central neural pathways is extremely valuable in treating the patient with chronic neuropathic pain by reducing central sensitization.

A regular schedule of local anesthetic blocks can be an important therapeutic intervention provided by the oral and maxillofacial surgeon for the chronic facial pain patient. The initial injections should be as well localized as possible and use short-acting local anesthetics. Therefore, if the pain is localized to a maxillary tooth, a small amount of local infiltration at the apex of the tooth (often without the use of topical anesthetic, which may obscure the results) would be performed with 3% mepivacaine. In the mandible, the bicuspid teeth and all teeth anterior to the bicuspids are amenable to a local anesthetic infiltration. Mandibular molars may require local infiltration along with a periodontal ligament injection. Alternatively, an inferior alveolar nerve block can be given for the mandibular molars, but the diagnostic results of this injection are less specific because of the broader anatomic area of anesthesia obtained. If the local anesthetic injection adjacent to the suspected tooth fails to provide any pain relief, it is often helpful to give an injection into the adjacent muscle of mastication (usually the masseter, temporalis, or lateral pterygoid) because masticatory muscle spasm is a common source of referred dental pain ( Figure 8-1 ).

The local anesthetic injection is often delivered following the clinical and radiographic examination but before the discussion with the patient concerning the diagnosis and treatment recommendations. This gives the local anesthetic time to take effect before discharging the patient. Because the patient has provided the clinician with a preinjection subjective assessment of their pain intensity using he visual analog scale (0 = no pain, 10 = the most severe pain), the patient is then asked to provide a number on the visual analog scale, 5 minutes following the administration of the injection. If the initial response does not provide at least a 50% reduction in the pain, then the clinician may consider providing additional local anesthetic injections in an attempt to identify the peripheral source (or trigger) of the pain. The reason for the initial use of a short-acting local anesthetic, such as 3% mepivacaine is that certain patients may find that the local anesthetic sensation provides a dysesthesia with further exacerbation of the pain. Although this is rare, it does occur in some chronic orofacial pain patients. Individuals who have had trigeminal nerve injuries (from surgery or trauma) seem to be more susceptible to exacerbation of pain with trials of local anesthetics.

If the short-acting local anesthetic provides a significant reduction in pain (greater than 50%), then the oral and maxillofacial surgeon may consider administration of a long-acting local anesthetic, such as 0.5% bupivacaine with epinephrine 1 : 200,000 at the same site of the initial injection. This may be performed at the first visit, or at times it can be saved for a subsequent visit, to provide a stepwise approach for the patient to gradually treat and improve their pain condition. Giving the patient hope, confidence, and pain relief plays an important role in reversing the deleterious effects of chronic pain.

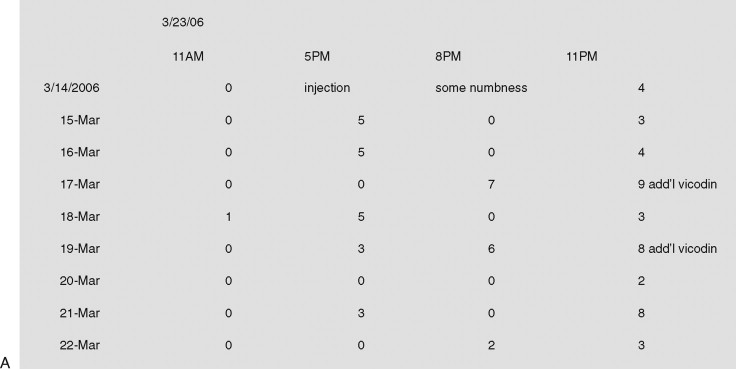

The time, site, dose, and response to the injections are recorded carefully in the chart, and the patient is also given the task of keeping a log of their pain level following the initial injection. This log provides very important diagnostic and potentially therapeutic information ( Figure 8-2 ).

The log includes the following information:

- •

Preinjection pain level on the VAS

- •

Time of injection

- •

Location of injection

- •

Local anesthetic agent(s) used and dosage

- •

Patient response after 5 minutes on the VAS

- •

Patient response after 15 minutes on the VAS

- •

Patient VAS every hour following the injection (patient takes the log home)

- •

Time when the local anesthetic effect has worn off

- •

Pain VAS every hour following this for 24 hours

If the log demonstrates that the pain returns to preinjection levels following the local anesthetic injection, this provides additional evidence that the primary pain source is local or there is a trigger that is local. If the log demonstrates further effective pain relief following the cessation of the local anesthetic effect, this provides evidence that there is a central neuropathic component of the pain that is being exacerbated by peripheral impulses. These peripheral impulses may be scar tissue or neuromas from previous trauma. However, regardless of the exact mechanism for the pain, the response of continued pain relief following a wearing off of the local anesthetic effect is an indication that the central nervous system has had a chance to temporarily recover from the barrage of ascending impulses from peripheral nerve pathways. This then provides the clinician with a therapeutic intervention, which has potential to reduce the central mediated component of the pain by blocking peripheral painful sensory impulses.

The results of diagnostic local anesthetic injections in chronic facial pain patients are often equivocal. There are some patients who have no benefit and others who have varying responses at different times. In this scenario, it is not necessarily recommended to completely abandon the use of local anesthetics. If the results of the injections are equivocal, the clinician may then proceed to try to block the pain farther proximally. Therefore, the patient who had an equivocal response to a local infiltration in the maxillary anterior region may need a trial of infraorbital nerve blocks. Those who had an equivocal response to posterior maxillary molar infiltrations may benefit from a posterior superior alveolar nerve block or a V2 division block administered through the pterygopalatine fissure or the greater palatine canal. Individuals who have equivocal responses to injection of mandibular teeth may benefit from a mental nerve block, lingual nerve block, buccal nerve block, and/or an inferior alveolar nerve block. Each trial of local anesthetic injections is assessed using the aforementioned local anesthetic log. These logs provide very useful information even when the response to the local anesthetic does not provide pain relief. A review of the temporal tendencies of the pain will provide useful information on factors that exacerbate the pain and may also enable the clinician to more effectively time and dose medications to reduce or prevent the onset of the pain (see Figure 8-2 ).

RULE OUT PATHOLOGIC CONDITIONS LOCALIZED TO THE SURROUNDING ANATOMIC STRUCTURES

The complex regional anatomy of the oral and maxillofacial region makes diagnosis and treatment of pathologic conditions in this region difficult. Pain is the most common reason for a patient to seek treatment. The trigeminal nerve is responsible for transmitting sensory impulses from the head and neck region to the central nervous system. The variable anatomy of the branches of the trigeminal nerve along with the complex branching and crossover of nerve fibers makes the head and neck region very susceptible to referred pain patterns, where the site and source of pain are different. One of the goals of the initial visit is to rule out any local pathologic condition that is amenable to routine treatment by the oral and maxillofacial surgeon. Therefore, anatomic regions adjacent to the oral cavity, maxilla, and mandible may have a localized pathologic condition that can cause referred pain. Failure to diagnose pathologic conditions from surrounding structures can contribute to the onset of chronic orofacial pain.

A common example of this is the patient with maxillary sinusitis. These patients will often come to their dentist complaining of multiple painful posterior maxillary teeth. If the patient undergoes several dental treatments that fail to reduce the pain (endodontic therapy, apicoectomy, extraction therapy), not only is the source of the pain still present, but the repeated tissue damage from invasive treatment can set up the environment for the onset of chronic orofacial pain. If the correct diagnosis of maxillary sinusitis is made too late, appropriate sinus treatment may alleviate the pain from the sinusitis, but may have no effect on the chronic central mediated pain that was created by multiple failed dental treatments.

Another commonly misdiagnosed condition involving surrounding structures is temporal arteritis. These patients have severe pain associated with chewing. The pain tends to be localized to the temporal region, but can also be referred to the temporomandibular joint, and thus, is frequently misdiagnosed. An additional factor that contributes to this misdiagnosis is that the patient population with temporal arteritis is often significantly older than those with typical inflammatory temporomandibular joint pathologic conditions. Therefore on clinical examination, chronic osteoarthritis is often discovered with crepitus of the temporomandibular joints on auscultation and evidence of degenerative changes of the mandibular condyles seen on panoramic radiographs. Thus, these patients often undergo treatment for temporomandibular joint osteoarthritis that fails to alleviate the symptoms. The use of nonsteroidal antiinflammatory medications (NSAIDs), a softer diet, physical therapy, and night guard appliances will not alleviate the symptoms of temporal arteritis. In fact the delay in making a correct diagnosis can lead to permanent impairment of vision. There are several ways of preventing misdiagnosis of temporal arteritis. Patients with temporal arteritis will frequently have pain to palpation of the temporal artery. An elevation in the serum erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) is a nonspecific laboratory finding in patients with temporal arteritis. A definitive diagnosis requires a temporal artery biopsy. Elderly patients who do not fit the typical profile of the younger patients who are susceptible to inflammatory temporomandibular joint disease should all be suspected of having temporal arteritis until it is ruled out.

PERFORM A CRANIAL NERVE EXAMINATION AS A ROUTINE PART OF THE CLINICAL EXAMINATION OF THE CHRONIC OROFACIAL PAIN PATIENT

The cranial nerve examination is an essential part of any thorough head and neck examination. For patients with chronic orofacial pain conditions, a thorough cranial nerve examination is essential and should be performed frequently at follow-up visits. The cranial nerve examination takes very little time, and if there are no abnormalities, it may seem to the clinician that the information was not very helpful. However, this is not the case because an abnormal cranial nerve examination usually represents a significant pathologic condition. The following is a very brief gross cranial nerve examination that potentially can yield very important information:

- •

Cranial Nerve I: Have the patient close his or her eyes, close one nostril, and ask them to identify a smell (e.g., alcohol).

- •

Cranial Nerves II, III, IV, VI: Check papillary reflexes to light and accommodation. Check extraocular eye movements in three planes.

- •

Cranial Nerve V: Test sensory branches of V1, V2, V3 with a cotton swab and look for differences between left and right. Check motor division of V by looking for deviation of the mandible upon opening, representing unopposed action of the lateral pterygoid muscle. Ask the patient to clench and check for masseter and temporalis tone bilaterally.

- •

Cranial Nerve VII: Ask patient to demonstrate facial movements by raising the eyebrows, shutting the eyes, moving the nose, smiling, and pursing lips.

- •

Cranial Nerve VIII: The examiner rubs his or her fingers together in front of each ear, and differences between the right and left sides are noted.

- •

Cranial Nerves IX and X: Test the gag reflex. IX is sensory, and X is motor.

- •

Cranial Nerve XI: Have patient elevate shoulders and look for asymmetry.

- •

Cranial Nerve XII: Ask patient to protrude their tongue and look for deviation to one side. Unopposed action of the right or left genioglossus muscle will cause deviation to the side that is impaired.

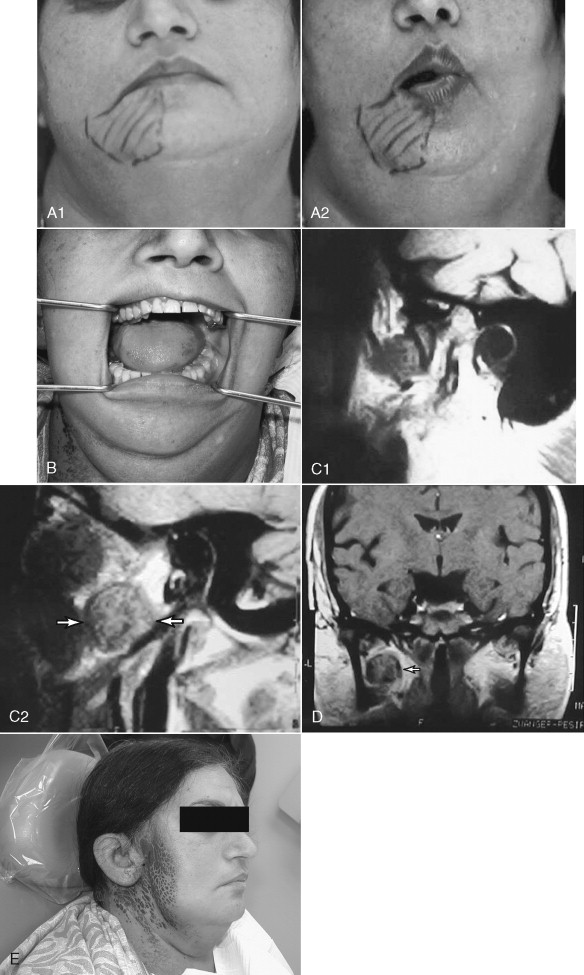

When checking the facial nerve, an abnormal finding may be complete paralysis of the muscles of one side of the face or may only involve the lower half of the face. The distinction between these two types of facial nerve dysfunction is very important. The temporal branches of the facial nerve on one side receive input from upper motor neurons bilaterally as a result of decussation of these nerve fibers in the brain. The lower peripheral branches of the facial nerve receive upper motor neuron input from the ipsilateral side only. Thus, a centrally located lesion that affects the facial nerve will cause paralysis of only the lower half of the face. A peripherally located lesion that affects the facial nerve, such as a parotid tumor, is likely to cause paralysis of all of the branches of the facial nerve on the side of the tumor ( Figure 8-3 , A).

Deviation of the mandible upon opening is a sign that is common in chronic facial pain patients who have a temporomandibular joint disorder. The clinician will often assume that the facial pain and deviation of mandibular opening is due to failed translation of a pathologic ipsilateral temporomandibular joint. However, it is extremely important for the clinician to also check the motor function of the trigeminal nerve because deviation of the mandible can also be caused by a pathologic condition impinging on this nerve. Failure to check for the presence of motor function of the trigeminal nerve can lead to a significant misdiagnosis, with treatment of a temporomandibular joint condition when in fact the patient has a tumor or lesion causing impingement of the cranial nerve V ( Figures. 8-3, B-E ).

Patients with chronic orofacial pain often complain of the symptom of numbness. A careful history will reveal if there is any evidence of trauma or surgery that may have caused damage to the sensory nerves that innervate the oral and maxillofacial region. There are some chronic pain patients, with no history of acute trauma to the branches of the trigeminal nerve, who complain of facial numbness. Individuals who complain of sensory disturbances require a careful sensory examination. The simplest form of this examination is to ask the patient to close their eyes while the examiner tests for normal sensation to touch, using a cotton applicator. The cotton applicator goes from the area where the sensation is normal toward the area that is abnormal, asking the patient to identify when the change in sensation has taken place. The examiner draws a mark at that site (make up pencil) and repeats the examination from different locations, going from normal to abnormal. The examiner then draws a map of the area with altered or reduced sensation and photographs of this area are taken. If the area of altered sensation follows the distribution of one of the sensory nerves, then this is highly suggestive of a pathologic condition or trauma that is altering normal sensory activity ( Figure 8-4, A,B ). Further investigation of both peripheral and central causes of altered sensory activity are required. Local trauma, surgical trauma, and pathologic conditions can often be diagnosed with radiographs and diagnostic images (CT or MRI). Pathologic conditions of the central nervous system that alter sensation require an MRI and/or CT of the brain. Demyelinating diseases, such as multiple sclerosis and intracranial tumors, such as acoustic neuroma, are common central causes of altered sensation of the oral and maxillofacial region. If the map of the area of altered sensation does not follow the anatomic distribution of one of the branches of the trigeminal nerve, it is more likely that the altered sensation is due to a musculoskeletal disorder. Patients suffering from masticatory muscle spasm often have intermittent areas of altered sensation that do not follow an anatomic distribution. This is most likely due to the effect of increased muscle activity causing intermittent impingement of terminal sensory fibers.

CONSIDER SYSTEMIC PATHOLOGIC CONDITIONS THAT CAN CAUSE FACIAL PAIN

The key to diagnosing systemic pathologic conditions that can cause pain is taking a careful history. Systemic musculoskeletal disorders, such as fibromyalgia, rheumatoid arthritis, and osteoarthritis, commonly affect the temporomandibular joint and surrounding structures. The pattern of the pain and the quality of the pain often provide significant clues to a systemic cause. Unilateral shocklike facial pain is characteristic of trigeminal neuralgia. If this type of pain is accompanied with a history of severe fatigue and patches of sensory alterations in other areas of the body in a young adult, this would be highly suggestive of multiple sclerosis, which is associated with a higher frequency of trigeminal neuralgia. A history of herpes zoster would be more suggestive of postherpetic neuralgia.

A recent study of patients experiencing significant cardiac ischemia revealed that craniofacial pain was the only complaint in 6% of individuals. In this study of cardiac ischemia symptoms, an additional 32% of patients had craniofacial pain along with concomitant pain in other regions. The most common craniofacial pain locations were the throat, mandible, temporomandibular joint, and teeth. Overall the study concluded that in patients with cardiac ischemia who did not have chest pain, craniofacial pain was the most dominant symptom. Patients who have risk factors for coronary artery disease, with atypical orofacial pain should be suspected of having cardiac ischemia. In particular if the pain history reveals physical activity to be a precipitating cause of the pain, the clinician should be highly suspicious of cardiac ischemia. The implications for the dentist and oral and maxillofacial surgeon are significant because cardiac ischemia and acute myocardial infarction require immediate referral and management.

RECOGNIZE AND TREAT BOTH PERIPHERAL AND CENTRAL MEDIATED PAIN

An important principal in the management of the patient with chronic orofacial pain is to establish accurate diagnoses. However, the process of performing an appropriate work-up is frequently lengthy and may yield negative or equivocal results. During this process, it is important for the clinician to provide therapies that reduce the pain. A key principal in the treatment of orofacial pain is to block the peripheral input of noxious stimuli from reaching the central nervous system to prevent sensitization of ascending pathways in the central nervous system. Interventions that successfully reduce the pain by reducing peripheral noxious stimuli are not only temporarily beneficial, but have important therapeutic effects because they reduce stimulation of the central nervous system. Thus a local anesthetic that blocks peripheral sensory nerves also reduces the volley of impulses reaching the subnucleus caudalis of the brainstem. This in turn reduces the stimulation of the ascending spinothalamic tract of the spinal cord that eventually reaches the cerebral cortex and is recognized as pain. Because central neuropathic pain is characterized by excessive excitability of the ascending nerve pathways, the local anesthetic block reduces this excitability. This helps to explain the phenomenon experienced by many chronic orofacial pain patients of obtaining significant pain relief beyond the duration of the local anesthetic.

There are numerous modalities that the clinician can use to reduce peripherally mediated pain. Medications that provide antiinflammatory effects (both steroidal and nonsteroidal) have the capacity to reduce the noxious stimuli by reducing stimulation of the peripheral nociceptors caused by tissue injury. Muscle relaxant medications can be helpful indirectly by reducing painful muscle contraction that often occurs as a response to injury. This is particularly true in individuals who have painful musculoskeletal disorders of the head, such as temporomandibular joint synovitis or masticatory muscle spasm. As described previously, a series of local anesthetic injections designed to block the peripheral pain impulses can have important therapeutic effects.

The reduction of central mediated pain simultaneously with the reduction of the peripheral mediated pain offers the chronic orofacial pain patient the best chance of effective pain relief. Central mediated pain can be reduced with a variety of medications. Anticonvulsant mediations (gabapentin, pregabalin, carbamazepine) are helpful, but these medications require careful titration to eventually achieve a therapeutic dose. Some patients are not able to tolerate the side effects of these medications as the dosage is increased. The use of narcotic analgesics in patients with chronic orofacial pain is controversial. The opioid class of medications acts centrally to reduce pain. However, the potential for tolerance, abuse, and addiction are possible with narcotic analgesics when their use is not carefully supervised and documented by the treating clinician. Short-acting narcotic analgesics are not indicated in the treatment of chronic orofacial pain. The short duration of pain relief with medications, such as Tylenol with codeine, hydrocodone, and oxycodone, result in a brief period of reduced pain often followed several hours later by a return of severe pain, resulting in a cycle characterized by an increasing frequency and dose of narcotic medication. In spite of our knowledge about the negative effects of short-acting narcotics in the chronic orofacial pain patient, many patients arrive at the oral and maxillofacial surgeon’s office with a long history of dependence on short-acting narcotics. In certain select patients, long-acting narcotic analgesics are indicated and are usually prescribed in a pain management center. If the oral and maxillofacial surgeon decides to manage patients with long-acting narcotic analgesics, it is especially important to have a signed contract with the patient to provide ground rules for their use. It is extremely important to avoid having multiple clinicians prescribing medications for pain management, and thus communication and coordination with all of the patient’s physicians is very important. In general it is best for only one treating clinician to be in charge of prescribing pain medications.

SUBSEQUENT VISITS OF THE CHRONIC OROFACIAL PAIN PATIENT

Regularly scheduled follow-up visits are a necessary part of management of the chronic orofacial pain patient. Each subsequent visit requires that the clinician follow an organized protocol which should include the following:

- 1.

Review of the diagnoses and treatment recommendations from the previous appointment

- 2.

Subjective assessment by the patient as to whether the pain is the same, better, or worse than the previous appointment

- 3.

Detailed assessment of the pain to determine if it has changed with respect to:

- a.

Location

- b.

Intensity (visual analog scale)

- c.

Frequency

- d.

Character

- e.

Temporal pattern

- f.

Reevaluation of factors that increase and decrease the pain

- a.

- 4.

Assessment concerning patient compliance with the treatment recommendations from the previous visit

- 5.

Assessment of any side effects or complications from the treatment recommendations of the previous visit

- 6.

Review of any changes in the medical history

- 7.

Review of all current medications and compliance with these medications

- 8.

Patient assessment of the efficacy of each of the treatment recommendations from the previous visit

- 9.

Thorough head and neck examination including cranial nerve examination

- 10.

Review of all new diagnostic images and laboratory test results ordered

- 11.

Reassessment of the differential diagnoses

- 12.

Treatment plan with the inclusion of the date required for follow-up

- 13.

Projected plan for the next step in treatment should the patient not improve or if the symptoms increase

REEVALUATE DIAGNOSES CONTINUALLY

The follow-up appointments for chronic orofacial pain patients can vary in length, but usually 30 minutes is an adequate amount of time for this reevaluation process. It is very important for the clinician not to evaluate the patient with a preconceived notion of the diagnoses. Rather it is better for the clinician to view each subsequent visit with a fresh viewpoint, challenging the accuracy of the working differential diagnoses based on the patient’s response to treatment and changes in the history and clinical examination.

MINIMIZE VARIABLES WHEN INSTITUTING CHANGES IN TREATMENT

The first consultation visit should ultimately result in a differential diagnoses and treatment based on the diagnoses. Initially, this will involve multiple treatment modalities frequently involving multiple medications. At subsequent visits, the diagnoses should become clearer as the patient responds or fails to respond to treatment. Another key principle in the subsequent evaluation and management of the chronic orofacial pain patient is when providing changes in treatment, it is preferable to make only one change (or the fewest number of changes) at a time . This concept of management helps to reduce multiple variables in treatment changes that may further confuse evaluation and management of the chronic orofacial pain patient. For example, if a medication that has been prescribed at the previous appointment was not effective or created an untoward side effect, it is generally best to replace one medication with another single medication. In this way, the effect of this medication change can be assessed accurately at the next appointment. If two or more medications are added to the treatment regimen, then any improvement or untoward effect cannot be attributed with certainty to either of the medications that were tried. An example of this would be the patient with chronic orofacial pain in whom the differential diagnosis includes both atypical facial neuralgia and a chronic infection. If the clinician decides to treat the patient with both a course of an anticonvulsant (e.g., gabapentin) and an antibiotic, then a favorable response to this treatment may further confuse the diagnosis and appropriate treatment regimen.

There are many exceptions to the one treatment change principle that rely on the judgment of the clinician and the multiplicity of diagnoses being managed. The initial visit basically maps out a plan and provides treatment for each individual diagnosis, so initial management with multiple therapies and medications are common. However, once the diagnoses become more firmly established, providing one treatment change is very helpful to the clinician in providing appropriate and successful management of these complex patients. At the end of each follow-up appointment, it is important for the clinician to have a plan, should the patient not respond favorably to the treatment recommended at the previous appointment. For example, if the patient with masticatory muscle spasm has been unsuccessfully treated with a muscle relaxant, then the clinician may opt to try a different medication. The clinician may note in the chart that at the follow-up appointment if the second muscle relaxant was unsuccessful in reducing symptoms, a series of muscle trigger injections may be the next course of action. The key principle here is for the clinician to have a plan in advance based on the patient’s response to treatment.

AVOID CHANGES IN TREATMENT IF PAIN LEVELS ARE IMPROVING

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses