Behavior guidance is a continuum of techniques, basic and advanced, fundamental to the provision of quality dental care for pediatric patients. This practice must be individualized, pairing the correct method of behavior guidance with each child. To select the appropriate technique, the clinician must have a thorough understanding of each aspect of the continuum and anticipate parental expectations, child temperament, and the technical procedures necessary to complete care. By effectively using techniques within the continuum of behavior guidance, a healing relationship with the family is maintained while addressing dental disease and empowering the child to receive dental treatment throughout their lifetime.

Key Points

- •

Behavior guidance is a continuum of skills spanning from basic to advanced techniques. Providing care to children requires understanding of the full continuum.

- •

Patient assessment includes anticipation of parental expectations, child temperament, and technical procedures. It dictates the appropriate behavior guidance technique for each child.

- •

Basic behavior guidance encompasses communicative behavior guidance, audiovisual distraction, nitrous oxide/oxygen inhalation, and delayed or alternative restorative treatment.

- •

Advanced behavior guidance encompasses protective stabilization, sedation, and general anesthesia. Its use should be restricted to those who have advanced training.

- •

By implementing the appropriate behavior guidance strategy, a healing relationship is maintained and the child is equipped to receive dental treatment throughout their lifetime.

Introduction

Most treatments provided within the comprehensive dental care of children are relatively simple, yet many practitioners find that delivering high-quality care to young children is challenging, which is not because of the technical procedures that must be rendered, but because they are performed on a child. The provision of dental care to children presents unique challenges and opportunities. To effectively treat children, providers must be prepared to address child behavior and leverage appropriate behavior guidance techniques.

Behavior guidance eases fear and anxiety and promotes an understanding of the need for good oral health. This two-way therapeutic relationship is fundamental to the strategies presented within this article. These strategies, known as the discipline of behavior guidance, are presented here as a continuum. Thoughtful and individualized selection of the appropriate approach within this continuum determines the successful practice of pediatric dentistry.

Introduction

Most treatments provided within the comprehensive dental care of children are relatively simple, yet many practitioners find that delivering high-quality care to young children is challenging, which is not because of the technical procedures that must be rendered, but because they are performed on a child. The provision of dental care to children presents unique challenges and opportunities. To effectively treat children, providers must be prepared to address child behavior and leverage appropriate behavior guidance techniques.

Behavior guidance eases fear and anxiety and promotes an understanding of the need for good oral health. This two-way therapeutic relationship is fundamental to the strategies presented within this article. These strategies, known as the discipline of behavior guidance, are presented here as a continuum. Thoughtful and individualized selection of the appropriate approach within this continuum determines the successful practice of pediatric dentistry.

An overview of behavior guidance

The American Academy of Pediatric Dentistry (AAPD) defines behavior guidance as:

“A continuum of interaction involving the dentist and dental team, the patient, and the parent directed toward communication and education.”

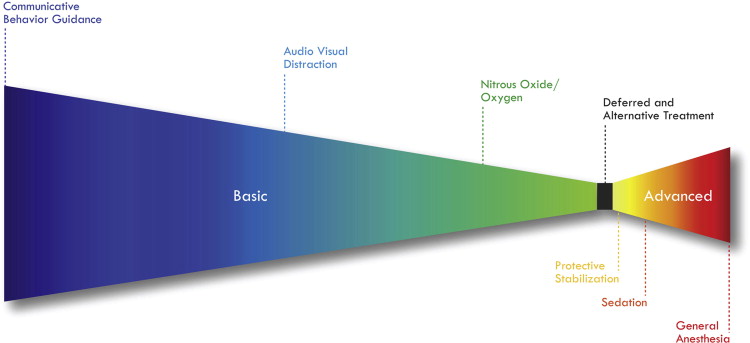

The individual techniques in behavior guidance are categorized as basic behavior guidance and advanced behavior guidance ( Table 1 ). This article does not discuss each element of behavior guidance in detail, but enables the reader to visualize each technique within the conceptual framework of a continuum ( Fig. 1 ).

| Behavior Guidance | |

|---|---|

| Basic | Advanced |

|

Protective stabilization |

| Sedation | |

| General anesthesia | |

|

|

|

|

The continuum of behavior guidance: principles of practice

With time, each practitioner develops his or her own unique style of behavior guidance. This skill set is developed through perspective gained in training and clinical experience. A unique practice style is what distinguishes the provider as an individual and allows them to practice from a place of conviction and authenticity . Although each style of behavior guidance may vary, there are certain fundamental principles of practice that should not. For example,

- •

A positive, healing, therapeutic relationship is maintained between the child, the parent, and the dentist. This healing relationship is predicated on trust, effective communication, empathy for the patient, and provider reliability.

- •

There is one diagnosis for a given condition, yet there are typically multiple acceptable treatment options. Child behavior may require variation in the treatment provided.

- •

Child behavior may dictate variation in the methods used to deliver care.

- •

Treatment that is not definitive may be performed to effectively treat the disease while preserving the therapeutic relationship.

These principles are the basis of patient-centered care. This approach requires that the practitioner address not only the disease but also the patient’s experience of the illness. In pediatric dentistry, this means that special precautions are taken to ensure that the diseased teeth are not just treated but cared for in a manner that is considerate of each child’s individual needs-child centered care. In 1895, McElroy recognized that “although the operative dentistry may be perfect, the appointment is a failure if the child departs in tears.” If the tooth is saved but the patient’s developing psyche is damaged in the process, child centered care was not provided.

The AAPD states that behavior guidance “is not an application of individual techniques created to deal with children, but rather a comprehensive, continuous method meant to develop and nurture the relationship between patient and doctor, which ultimately builds trust and allays fear and anxiety.” The aim should be not only to eliminate the immediate dental problem but also to equip the patient with the coping skills necessary to maintain optimal oral health throughout their lifetime.

Patient assessment

To effectively provide pediatric dental care, a behavior guidance approach that is appropriate to each child is selected. The process of choosing the approach is as much an art as it is a science. A well-balanced practitioner should possess a diverse skill set that can accommodate the wide variety of children who present to them for care. Thus, perhaps the most important skill that the clinician must master is anticipation . For example, it is imperative that the clinician anticipate:

- •

Parenting style and expectations for dental care . Some parents may refuse advanced behavior guidance such as sedation and general anesthesia (GA) for their child, whereas others demand it.

- •

Child temperament and coping ability . Some young children are not capable of coping with dental care in the clinic setting, whereas others sit peacefully during the operative procedures.

- •

Technical procedures necessary to complete care . The provider should anticipate those teeth that will require pulp therapy so that the materials will be on hand and the child is not made to wait for an excessively long period for the procedure to be completed.

An understanding of each of these elements will enable the dentist to select the treatment and behavior guidance method most appropriate to the child. It will also enable he or she to predict the potential behavioral complications before they arise, making accommodations to ensure a successful outcome.

The pretreatment patient assessment

Age-Appropriate Behavior

Children become more capable of accepting dental procedures as they grow older. Young children develop rapidly, and within six months, the child may be capable of tolerating procedures that they could not cope with earlier. This rapid development is the basis for the concept of deferred treatment. A 5-year-old child is often much more capable of receiving dental treatment than they were at age 3.5 or 4 years. However, if the treatment cannot be withheld without complications sedation or GA may be required ( Table 2 ).

| Age | Traits |

|---|---|

| Two | Likes to see and touch Very attached to parent Limited vocabulary with early sentence formation |

| Three | Less egocentric; likes to please Active imagination; likes stories Remains closely attached to parent |

| Four | Tries to impose powers Reaches out-expansive period Knows “thank you” and “please” |

| Five | Undergoes a period of consolidation, is deliberate Relinquishes comfort objects, such as a blanket or thumb |

Medical History

Critical review of the medical history will enable the practitioner not only to avoid treatments which could be unsafe for the patient but also will provide them with information on the child’s behavior. Particular emphasis should be placed on the psychological aspect of the history. Patients with autism, attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder, or developmental delay present unique behavioral challenges. Items such as school performance, the ability to socialize, and the ability to tolerate haircuts and medical procedures can be predictive of a child’s ability to cooperate in the dental office.

Presentation of Oral Disease

The presentation of oral disease can be a critical factor in selecting the behavior guidance approach. Factors to consider include, among others, the urgency of the condition, location (ie, anterior vs posterior teeth), and the time to tooth exfoliation. Treatment may deferred on an asymptomatic primary anterior tooth of a 7-year-old because it is nearing exfoliation, but it may be advisable to treat the same lesion on a 3-year-old.

Temperament

Temperament is defined as the behavioral style of a child or the manner in which the child interacts with the environment. Temperament affects a child’s behavior in a given situation. The clinician must match the temperament or behavioral style of the child with the environmental expectations and demands placed on them for a successful treatment. This concept is called goodness of fit. The implication is that those children who have an easy or adaptable temperament will often readily accept dental treatment. Likewise, those have more difficult temperament may have more difficulty tolerating dental treatment. Thus, the environmental expectations placed on them should be adjusted to fit their circumstances (ie, a different behavior guidance approach may be necessary for these children). The more experience the clinician has working with children, the more capable he or she will become at evaluating child temperament. As the dentist’s skill at evaluating child temperament improves, so does his or her ability to predict how well an individual child will cope with dental treatment. A brief evaluation should include:

- •

Child temperament (negative emotionality, activity, shyness, and impulsivity)

- •

Behavioral problems (externalizing and internalizing)

- •

Attention or concentration problems

- •

Verbal and behavioral interaction with the dentist

- •

Level of cooperation

- •

Level of attachment to parent

Parent/Caregiver Preferences

Although the focus in pediatric dentistry is the child, the practitioner must also address the caregiver when providing treatment. Caregiver factors to consider include:

- •

His/her own anxiety regarding dental care and/or the child’s appointment. Anxious parents may inadvertently transmit their emotions to the child, making it more difficult to complete care.

- •

Opinion on behavior-guidance techniques. Some parents of children with special health care needs refuse advanced behavior guidance such as immobilization, whereas others request that it be used for care.

- •

Preference of restorative materials. It may not be possible to use materials such as stainless steel crowns if they are thought by parents to be unacceptable for cosmetic reasons.

- •

Willingness to delay treatment versus desire for immediate definitive care. If the parent does not believe that he/she can return for the multiple follow-up preventive visits that are required in deferred treatment, comprehensive treatment using advanced behavior guidance may be preferable.

- •

Attitude toward oral health. The parent who has a fatalistic view of oral health does not believe that they have control over the disease outcome. Thus, their child may not be a good candidate for delayed treatment.

Basic behavior guidance strategies

Communicative Behavior Guidance

Most children who present for dental care can be treated using basic behavior guidance. The most fundamental of the basic strategies is communicative behavior guidance . This domain encompasses tell-show-do, voice control, nonverbal communication, positive reinforcement, and distraction. Tell-show-do is a technique formalized over 5 decades ago. It is the cornerstone of behavior management: a series of successive approximations. By explaining and demonstrating procedures before doing them, the dentist gains the child’s confidence. Voice control is a communicative technique that focuses on the delivery of the message the child receives. It is defined “modulation in voice volume, tone, or pace to influence and direct a patient’s behavior.” The modulation need not be in the direction of increased volume or a stern tone. In many cases lowering volume to a whisper is an effective way to gain the patient’s attention and extinguish negative behavior. Positive reinforcement is the practice of shaping a patient’s behavior through appropriately timed feedback and is used to reinforce helpful behaviors. Tangible reinforcements, such as prizes that a child receives at the completion of the dental visit, may also reinforce positive behavior and leave the child with a pleasant reminder of the dental appointment.

In appropriately applying communicative behavior guidance, it is imperative that the dentist interacts with the child at their developmental level. The delivery of the message plays a critical role in each of the communicative behavior guidance strategies. More than 50% of communication is expressed nonverbally in movement, gesture, and timing. Thus, the dentist’s self-confidence, posture, and poise are as critical as the words he/she speaks. This effect has been described elsewhere as calm-assertive energy . Often children misbehave because they are nervous or uncertain about being in the dental office. By adopting a calm-assertive approach, the dentist assures the child and maximizes the nonverbal aspects of communicative behavior guidance.

Audiovisual Distraction

Pain may be a cause for negative behavior in the dental chair. Therefore, the clinician may attempt to distract the patient to decrease the discomfort they experience during the procedure. A growing body of evidence shows that audiovisual (AV) distraction (eg, movies, music, and video games) can be very effective in decreasing pain experience for medical procedures. AV distraction has also been cited as a technological adjunct to traditional distraction techniques in the dental office. Specific advantages of AV distraction are:

- •

The patient can choose their preferred distraction (movie/game)

- •

Concentration on the screen image distracts from the view of dental treatment

- •

Sound of the program may decrease or eliminate dental handpiece noise

Despite its effectiveness in improving child behavior, AV distraction can also become problematic if the child is so immersed in the program that they cease to interact with the dentist. To minimize problems, the dentist must pay attention to appropriate program volume, continue to maintain communication with the child throughout the procedure, and reserve the right to remove the AV distraction should the child cease to follow instructions. AV distraction should be used in the same way as parental presence in the operatory; that is, if the child is cooperating and behaving appropriately the AV distraction is kept in place. If the child’s behavior begins to deteriorate, the dentist should tell her that to continue viewing the monitor, she needs to be cooperative (eg, be quiet, open her mouth, and be still). This regulation sets appropriate boundaries and extinguishes inappropriate behavior.

Parental Presence/Absence

Historically in Pediatric Dentistry, children were commonly separated from their parents in the waiting area. As society has changed and as dentists have begun seeing younger and younger children, the number of parents who accompany children in the treatment area has also increased. For some children separation from their parent may be emotionally challenging because they perceive their parent to be a source of comfort and protection. This is the basis for the technique of parental presence/absence. As with all behavior guidance techniques, both the parent and practitioner must agree on this technique before it is put into practice. When used, the parent agrees to leave the treatment area if requested by the practitioner. The dentist offers the child that the parent can remain in the operatory as long as they exhibit good behavior. If the child displays negative behavior, the parent is asked to leave. This technique has proven to be an effective way to extinguish negative behaviors for some children.

Nitrous Oxide/Oxygen Inhalation

Although it falls within the pharmacologic domain, nitrous oxide/oxygen inhalation (N 2 O/O 2 ) is still considered basic behavior guidance. Nitrous oxide is an excellent and safe anxiolytic with analgesic properties, which provides the patient a pleasurable sensation of relaxation with possible symptoms of body warmth, tingling of the hands and feet, circumoral numbness, auditory effects, and euphoria. At levels of 40% N 2 O it is suggested that it may produce good hard and soft tissue analgesia. Although it is not typically a substitute for effective local anesthesia, when the provider anticipates that injection of local anesthetic may be the primary behavioral trigger, N 2 O/O 2 can be effectively used in lieu of local anesthetic. One technique is to increase the relative percentage of nitrous oxide administered during components of the procedure, which could be more uncomfortable or which the child may have difficulty with, such as local anesthetic administration. In addition, for many patients N 2 O/O 2 decreases the gag reflex. Thus, although N 2 O/O 2 does not replace other behavior guidance techniques, it may be a helpful adjunct for decreasing discomfort and anxiety.

Alternative Restorative Treatments

When working with children, barriers to treatment must be anticipated, and the approach should also be flexible. In some circumstances, given the age, extent of disease, parental preference, time to tooth exfoliation, or clinician’s preference, conventional restorative treatment may not be possible or desirable. Alternative approaches may be considered in such circumstances. Alternative restorative treatments are not a specific behavior guidance technique; however, their use does fall within behavior guidance. In the continuum addressed here, alternative restorative treatments are positioned along with deferred treatment, immediately before the advanced behavior guidance techniques.

The interim therapeutic restoration (ITR) is a treatment that has been used in contemporary clinical practice because of such constraints. According to the AAPD,

“ITR may be used to restore and prevent further decalcification in young patients, uncooperative patients, or patients with special health care needs, or when traditional cavity preparation and/or placement of traditional dental restorations are not feasible or need to be postponed.”

As stated previously, deferring treatment for even 6 months may in some cases allow a child to mature to the point where he/she is capable of receiving care. Furthermore, some ITR restorations may function adequately until natural exfoliation, never requiring re-treatment with traditional restorative techniques.

ITR is most typically done with fluoride-containing glass ionomer materials. Local anesthetic is often not used, and minimal tooth structure is removed. Decay often remains after tooth preparation. ITR has its greatest success when applied to single surface or small 2 surface restorations. A meta-analysis showed survival rates for single-surface ITR-type restorations in primary teeth to be 95% at 2 years. Multi-surface restorations had 62% survival at 2 years, and sealants placed using the technique showed 1% new lesion incidence in the first 3 years. ITR should be used with informed consent in combination with a caries preventive program, which should include dietary and oral hygiene counseling, increased frequency of dental recall, monitoring of adequate fluoride exposure, and application of antimicrobial agents (eg, povidone iodine, xylitol, and chlorhexidine).

A novel alternative restorative approach called the Hall Technique has been discussed recently in the dental literature. It uses preformed stainless steel crowns cemented with glass ionomer cement onto carious primary teeth-without local anesthesia, tooth preparation, or decay removal. A well-designed randomized clinical trial shows that when used by general dentists in the United Kingdom, this technique produced outcomes superior to those of the conventional restorations placed. Parent, patient, and dentist satisfaction was also reported to be higher with this minimally invasive approach.

Within weeks after placement, the restorations equilibrate and occlusion is acceptable to the child. In a randomized trial, placement of 118 Hall crowns (89%) was rated as causing no apparent discomfort to the child. Seventy seven percent of children, 83% of caregivers, and 81% of dentists surveyed expressed a preference for the technique over the conventional restorative treatment. At 60 months, 92% of the restorations showed successful survival.

The Hall Technique is a relatively new restorative concept, and currently there is only a small body of research supporting its use. Therefore, more well-designed studies are needed to reach a conclusion regarding its effectiveness. Although it is uncertain whether this technique produces results similar to those of stainless steel crowns placed in the conventional fashion, the 2- and 5-year randomized clinical trial findings do suggest that it may become an attractive alternative to traditional techniques, particularly with children for whom the delivery of treatment under local anesthesia is not possible or desirable.

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses