The basis for patient retention is communication that involves the ability to understand and be understood. A patient seldom leaves a dental practice because of dissatisfaction with the margins of his or her composite restoration. However, the patient may leave because a staff member made it difficult to obtain a completed insurance claim form, was too busy to listen to a concern, made frequent errors on financial statements, or did not communicate the treatment plan in advance.

Service is not a result of clinical and cognitive skills but rather of attitudinal skills that evolve into a commitment to the welfare of others. Box 1-1 lists a variety of activities that indicate a service-oriented office.

Cultural Competency

The word culture comes from the Latin root colere, which means “to inhabit, to cultivate, or to honor.” In general, it refers to human activity. Culture is a shared, learned, symbolic system of values, beliefs, and attitudes that shapes and influences perception and behavior as an abstract “mental blueprint.” Cultural competency in dentistry refers to the ability of the system to provide care to patients with diverse values, beliefs, and behaviors, and it includes adapting treatment delivery to meet the patients’ social, cultural, and linguistic needs.

The dental professional’s work in the dental office is affected by culture when working with both patients and staff. People who grew up as part of a certain generation experience different situations during their formative years than do people who grew up in a different generation. Likewise, individuals who grew up in different cultures and with different languages often attach meaning to verbal communication in vastly different ways. Consequently, the dental staff must be aware of how to successfully communicate with members of different generations as well as members of different cultures. Culture makes a significant difference in communication. We learn to speak and give nonverbal cues on the basis of our culture. There are several issues that affect communication in the dental office.

First is the use of nonequivalent words. It is difficult to find a word in one language that is exactly equivalent to a word in an unrelated language. The use of technical dental terms makes this activity even more difficult. A good example of a nonequivalent word is demonstrated by an Eskimo individual, who has several names for snow, whereas a North American individual has only one: snow.

Another factor that affects communication within various cultures is silence. The United States is referred to as a talk or verbal society. For a North American, silence is often uncomfortable, and it is usually not considered appropriate in the American workplace. For example, if an American is criticized in the workplace, the person is allowed to respond verbally to show that the criticism has been understood and to explain how he or she will avoid making the mistake again. In the Philippines, however, the worker more likely would apologize with an action such as extending a favor to the one who has been offended but saying nothing.

Mexico is geographically close to the United States, but culturally it is much different from its northern neighbors. Mexico has a separate history and thus a different culture and different ways of doing and looking at things. The beliefs, expectations, ethics, etiquette, and social conduct of Mexicans are so different from those of Americans that Mexicans may almost seem to be from a different world. Thus, when treating Mexican patients or communicating with a Mexican staff member, one must be aware of the cultural differences and seek to understand how to most appropriately explain the method of practice in the dental office.

Many references are available for translating information into the languages of patients or staff members within the office. For instance, if the office has a significant number of Spanish-speaking patients, all efforts must be made to provide literature, health forms, questionnaires, and other communication in both English and Spanish. Spanish Terminology for the Dental Team is a small book published by Elsevier to help in this scenario. It is worth the effort, too, for the staff to enroll in a short course in the language that the patients or staff may speak.

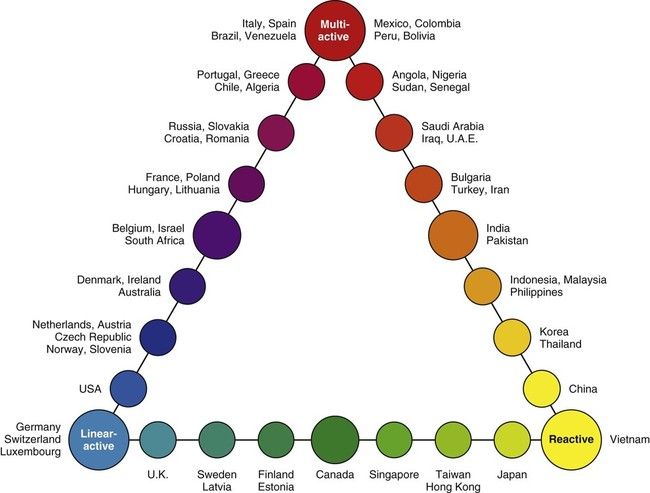

British linguist Richard Lewis plots the culture of different countries as it applies to the following three categories:

Thinking about these categories may be helpful for the dental professional who is presenting proposed treatment to a patient or discussing job tasks with a staff member; it will help him or her to better understand the potential reaction of the person to whom he or she is speaking. Figure 1-2 demonstrates how you may be able to examine the reactions of persons of various ethnic backgrounds using the Lewis model of linear-active, multi-active, and reactive variations (Box 1-2).

Organizational Culture

The term organizational culture has become well known in business. Many authors have defined organizational culture, but, perhaps for the purpose of dental management, it can best be defined as something that an organization or dental practice “is” rather than what it “has.” Organizational culture comprises the attitudes, experiences, beliefs, and values of an organization. It has been defined as the “specific collection of values and norms that are shared by people and groups in an organization and that control the way they interact with each other and with others outside the organization or dental practice.” Some authors even add to this definition the physical location of the organization, its dress codes, and the office arrangement and design.

Organizational culture can become very complex. However, the following list describes common organizational cultures that can be applied to a dental practice:

What does organizational culture mean for a new employee or an interviewee looking at a prospective job? It is not easy to identify the type of culture during an hour-long interview, but, if a working interview is possible, the type of culture may soon be identified. This allows prospective employees to see whether the “hum” is there and whether the ethos of the practice fits with his or her individual values, beliefs, attitudes, and emotions.

Types of Dental Practices

In a solo practice, a dentist practices by himself or herself and is responsible for both the business and clinical components of the practice.

Alternatively, a group practice may be formed by more than one dentist either via a legal agreement with each other and managed by themselves, or it may be formed with a dental management company that manages the business aspect of the practice. In this case, the clinical portion of the group is governed by the dentists themselves. It is also possible for a group practice to be managed by an outside company that controls both the business and clinical components of the practice. However, each state does have responsibility for specifying the limitations of practice under that state’s dental practice act.

One of the primary differences between a large group practice and a traditional dental practice is ownership. Dentists in these settings may have an ownership stake or part of an ownership stake, but many are employees of the practice. The American Dental Association noted that, from 2010 to 2011, the number of large dental group practices had risen 25%.

General Dentistry

A dentist who practices all phases of dentistry is referred to as a general dentist. This person will have completed a specified program of study accredited by the American Dental Association’s Commission on Dental Accreditation. Depending on the school from which the candidate graduates, he or she will receive a DMD degree or a DDS degree. DMD stands for “Doctor of Dental Medicine,” whereas DDS

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses

Practice Note

Practice Note