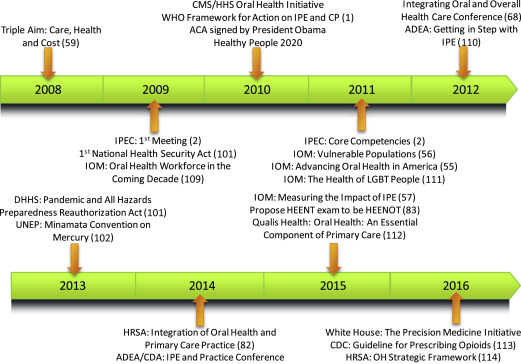

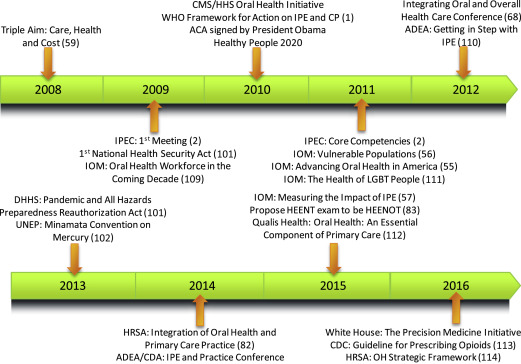

In 2009, the Interprofessional Education Collaborative (IPEC) was initiated. Its release of interprofessional collaborative practice (ICP) core competencies in 2011 was pivotal for the engagement of health care professionals, including dentistry; in patient-centered, collaborative efforts for interprofessional education (IPE); and ICP. Thereby, IPEC is helping to put into application, in North America, the 2010 World Health Organization (WHO) Framework for Action on Interprofessional Education and Collaborative Practice. This article introduces IPE/ICP in 5 phases of evolution, emphasizing dental influence and inclusion, from historical perspectives through current applications that are expanded on in the accompanying articles elsewhere in this issue.

Key points

- •

Interprofessional collaborative practice related to oral health has existed across dentistry’s history and is recently reinforced by changes in the US health care system.

- •

The Interprofessional Education Collaborative and its core competencies facilitate dental awareness and participation in collaborative practice, particularly for North America.

- •

The World Health Organization supports interprofessional education and collaborative practice as means toward solving health care workforce shortages.

- •

The ongoing development of interprofessional education and collaborative practice, with academic and clinical applications, contributes to the creation of concepts and support designed to achieve optimal health status for individuals and populations.

- •

Topics selected for this issue review interprofessional history, models, education, clinical practices, emerging applications, and resources.

Introduction

The historical influences by oral health care providers on nonoral health care and by nonoral health care providers on oral health care, deserve attention in consideration of the routes of how clinicians in dentistry have got to where they are and how they move forward. In current advancements of interprofessional education (IPE) and interprofessional collaborative practice (ICP), the inclusion and influences of dentistry seem logical, but this may not have always been the case.

The fundamental definitions of IPE and ICP come from the World Health Organization (WHO). Interprofessional Education is “When students from two or more professions learn about, from and with each other to enable effective collaboration and improve health outcomes.” Interprofessional Collaborative Practice is “When multiple health workers from different professional backgrounds work together with patients, families, careers, and communities to deliver the highest quality of care.”

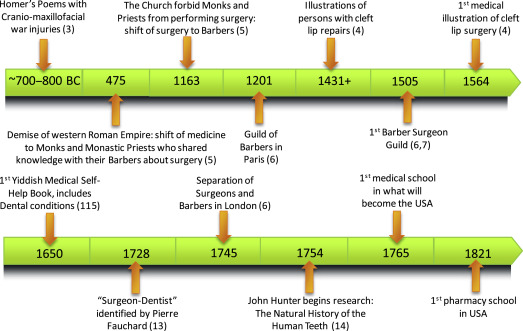

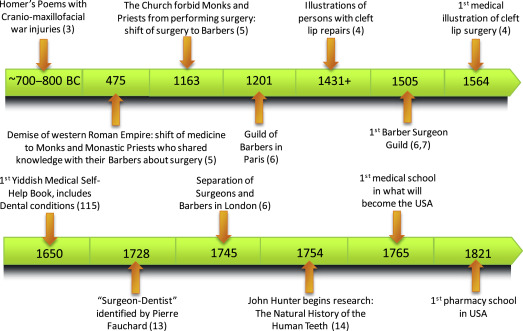

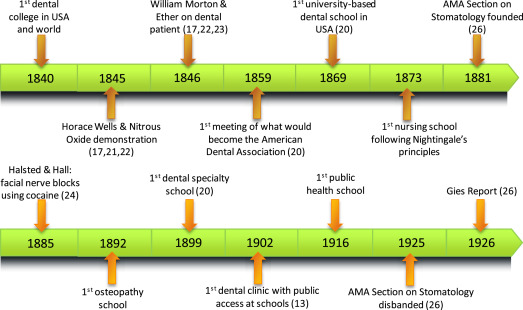

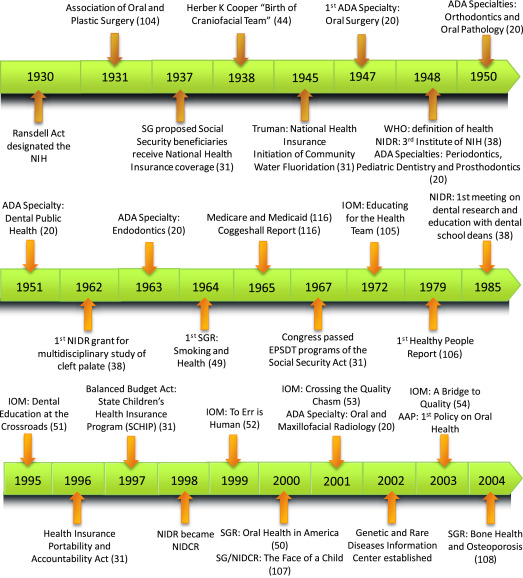

The evolution of IPE and ICP incorporates an extensive number of events and details. Hence, this article and the accompanying articles in this issue are selective. The aims are on positive aspects of collaborations, centered on dentistry and focus on the Interprofessional Education Collaborative (IPEC) health professional partners of dentistry, medicine, nursing, pharmacy, public health, and osteopathic medicine. The structure of this article is on 5 phases of IPE/ICP history that emerged during the course of our study spanning from Predentistry to Interprofessional Education/Interprofessional Collaborative Practice with Dentistry . The reader is referred to the accompanying Figs. 1–5 as a timeline through this evolution of the respective phases for the topics discussed in the text as well as with a few additional items which were added to help with historical context.

Introduction

The historical influences by oral health care providers on nonoral health care and by nonoral health care providers on oral health care, deserve attention in consideration of the routes of how clinicians in dentistry have got to where they are and how they move forward. In current advancements of interprofessional education (IPE) and interprofessional collaborative practice (ICP), the inclusion and influences of dentistry seem logical, but this may not have always been the case.

The fundamental definitions of IPE and ICP come from the World Health Organization (WHO). Interprofessional Education is “When students from two or more professions learn about, from and with each other to enable effective collaboration and improve health outcomes.” Interprofessional Collaborative Practice is “When multiple health workers from different professional backgrounds work together with patients, families, careers, and communities to deliver the highest quality of care.”

The evolution of IPE and ICP incorporates an extensive number of events and details. Hence, this article and the accompanying articles in this issue are selective. The aims are on positive aspects of collaborations, centered on dentistry and focus on the Interprofessional Education Collaborative (IPEC) health professional partners of dentistry, medicine, nursing, pharmacy, public health, and osteopathic medicine. The structure of this article is on 5 phases of IPE/ICP history that emerged during the course of our study spanning from Predentistry to Interprofessional Education/Interprofessional Collaborative Practice with Dentistry . The reader is referred to the accompanying Figs. 1–5 as a timeline through this evolution of the respective phases for the topics discussed in the text as well as with a few additional items which were added to help with historical context.

Phase 1. Predentistry

Reports of craniomaxillofacial abnormalities and the human desires to have them corrected have existed for a long time. These conditions earned attention in epic poetry, such as in Homer’s Iliad , recounting craniomaxillofacial war injuries thousands of years ago and in Gothic and Renaissance paintings depicting cleft lip repairs such as by Paré.

Sometime between the actions of Homer and Paré, an interprofessional practice (albeit by an individual rather than within a team) occurred, as seen via accounts of barber surgeons. The barber surgeon seems to have gained status as the unanticipated consequence of the church removing the surgical roles of priests and monks in 1163. Records of the first Guild of Barber Surgeons show its establishment in 1505, an event that may represent the creation of the first professional health care providers, building on the founding of the Guild of Barbers in Paris in 1210. Subsequently, physicians were recommended to not provide extractions but to leave such procedures laden with “unpleasant accidents” to the barbers, hence contributing to the separation of barbers and surgeons, which might have raised expectations of defining scope of practice for health care professions. Concrete evidence of this occurrence can be seen in 1745, when a Great Britain Parliament bill called for the separation of the surgeons and barbers of London.

Although it is perhaps commonly thought that the barber surgeon profession mainly existed outside the Americas, advertising by barber surgeons to have “teeth drawn, and old broken Stumps taken out very safely” have been found in North America. Fascinating details have been captured about these self-contained practitioners of integrated care, including the advertising of their work via the barber pole, which might even “suspend a string of extracted teeth.” From the perspective of the barbers, an interesting synopsis exists from 1904 by William Andrews. Andrews includes discussion of the derivation of the barber versus surgeon, and provides reports of barber surgeon performance conducted by both men and women. A validation exists for the importance of this group because PubMed ( http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/ ) retains a MeSH (Medical Subject Headings of the National Library of Medicine) term of “Barber Surgeon” with the following definition:

In the late Middle Ages barbers who also let blood, sold unguents, pulled teeth, applied cups, and gave enemas. They generally had the right to practice surgery. By the 18th century barbers continued to practice minor surgery and dentistry and many famous surgeons acquired their skill in the shops of barbers.

However, progress in scientific approaches, at least via published dissemination, to health care provision circa the mouth moved slowly. More than 200 years after the first establishment of a barber surgeons guild, John Hunter ( http://library.uthscsa.edu/2015/03/the-natural-history-of-human-teeth-john-hunter/ ) in 1754 began assessing “the natural history of the human teeth,” which led to publication in 1771 of “The Natural History of the Human Teeth: Explaining Their Structure, Use, Formation, Growth, and Diseases,” which was republished with additional information in 1778. His work contributed greatly to the understanding of the dentition and bone, including his allotransplant of teeth from one person to another. There could be some debate about whether he was a surgeon or a dentist, which may be a moot point because he seems to have been on-the-job trained in an academic anatomy laboratory and in military service. His interest in teeth included the relationship of teeth to the digestive system. Much of his original work and specimen collection remains at the Hunterian Museum in London ( http://www.hunterianmuseum.org/ ).

During Hunter’s life, the first Medical School, in what was to become the United States of America, was opened in Philadelphia at the University of Pennsylvania (1765) ( http://www.archives.upenn.edu/histy/features/1700s/medsch.html ). Subsequently, the first pharmacy school was also placed in Philadelphia, at the Philadelphia College of Pharmacy (1821), now part of the University of Sciences in Philadelphia ( http://www.usciences.edu/academics/collegesdepts/pcp ). Continuance of accounting of the first of health professions schools is discussed later, starting with the opening of the first dental school.

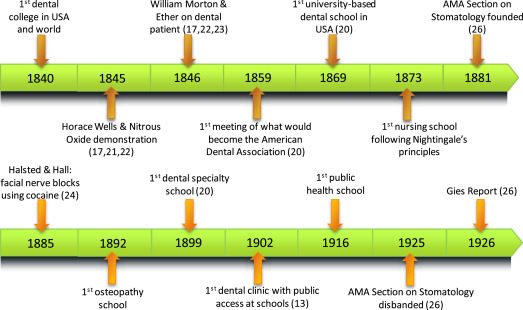

Phase 2. Establishing dental education

A notable unintended consequence happened when Chapin Harris’ repeated attempts, in 1837 and 1838, to have the University of Maryland Medical College include dental studies were denied. Hence, Harris organized the first dental school granting the Doctor of Dental Surgery (DDS) in the United States and the world, which was chartered in 1840 as the Baltimore College of Dental Surgery (BCDS), which later merged with the University of Maryland ( http://www.dental.umaryland.edu/museum/index.html/about-us/ ). Also in 1840, the first dental organization and the first dental journal came to be, thus dentistry became a true profession based on the tripod of organization, education, and literature. The first dental school associated with a university was at Harvard University, where, in choosing to keep with the Harvard tradition of awarding degrees in Latin, the granting of the Dentariae Mediciniae Doctoris (DMD) started in 1869. The first US nursing school adhering to Florence Nightingale’s nursing principles opened in 1873 as the Bellevue Hospital School of Nursing in New York City ( https://archives.med.nyu.edu/collections/bellevue-school-nursing ). The American School of Osteopathy in Kirksville, Missouri, opened in 1892 as the first school of osteopathy ( https://www.atsu.edu/museum/ ). The first dental specialty school was opened in 1899: the Angle School of Orthodontia, in St Louis, Missouri. The first school of public health did not open until 1916, when the Johns Hopkins School of Hygiene and Public Health was started in Baltimore, Maryland, with funding from the Rockefeller Foundation ( http://rockefeller100.org/exhibits/show/education/medical-education/public-health-at-johns-hopkins ). Given the 141-year spread of the creation of these first health professional educational institutions, it is reasonable to wonder whether the initiation of IPE would have been facilitated by simultaneous development of education for these and other health care professions.

Dentistry was involved, sometimes as the leader, with developments for the management and diagnosis of conditions of patients seen by multiple health care professionals. Several notable examples from the 1800s include the introduction of nitrous oxide in 1845, ether in 1846 (by BCDS graduate William T.G. Morton), nerve blocks in 1885, and dental applications of radiographs in 1896. However, these are select examples, and their histories show an often bumpy road to the development of dentistry with diversions into and from ICP.

During this period, organized dentistry was raised in America from several roots. The American Dental Convention, founded in 1855, encountered discontent that led to another effort to establish a dental association. In 1859, dentists from the American Dental Convention joined others, including dentists who had been members of the former American Society of Dental Surgeons (1840–1856), at a meeting in Niagara Falls, New York. This meeting of 26 dentists, from as far away as Illinois, Missouri, and Wisconsin, led to the formation of the American Dental Association (ADA).

Notable diversity was added among the dental profession in the United States via the accomplishment of dental school graduation for individuals who were not white, European men. Examples of such diversity are the dental school graduation in 1866 of Lucy Hobbs Taylor, the first woman; in 1869 of Robert Tanner Freeman, the first African American man; and in 1890 of Ida Gray Nelson, the first African American woman.

The Gies Report, which is the familiar name for the Dental Education in the United States and Canada: A report to the Carnegie Foundation for the Advancement of Teaching by William J. Gies, released in 1926, provides insight into interprofessional attitudes of the era, which amounted to clearer separation of the professions of medicine and dentistry. His summary of medical reaction is presented as:

As a result of these unfounded assumptions and of such misapprehensions of the import of dental disorders, by physicians for centuries, medicine gave little attention to the health of the teeth. Although the advance of civilization has been accompanied by accentuation of dental abnormalities, medicine persistently ignored the great desirability of careful observation in this field; and, sharing the popular belief that decay of teeth was unpreventable and loss of teeth unavoidable, physicians helped to bring about universal resignation to the supposedly inevitable incidence of dental imperfection and distress. Until recently, medicine viewed this situation with about as much concern as that excited by loss of hair from the scalp, and did little more to understand or to control the influences responsible for the one than for the other.

Gies went on in this report to provide evidence that dentistry merits a standing equivalent to a medical specialty. He recognized that local infections associated with oral disease may have consequences for other areas/systems of the body and recommended that both dentists and physicians need to be able to perform diagnosis and control “of numerous conditions of local or general disease.” Hence, “dentistry should no longer be ignored in medical schools, and its main health-service features should be given suitable attention in the training of general practitioners of medicine.” However, at the time of the report, the United States and Canada had statutes that would have required dental laws to be repealed if dentistry were to be moved into medicine as a specialty area, which was not welcomed by either medicine or dentistry. The Gies Report, which took 5 years to compile, has more than 600 pages and includes data on the US and Canadian dental schools, and the current (as of 1926) level of understanding of dental diseases, which suggested the need for research. Gies made other major contributions to dentistry, including being the founder of the International Association for Dental Research (including the American Division, which subsequently became the American Association for Dental Research [AADR]) and the Journal of Dental Research.

Also during this phase, the education of other health professionals went through initiation, evaluation, and modification. Abraham Flexner produced a report on medical education, published in 1910, calling for reorganization of medical education to ensure its science base. The education of public health workers was proposed in 1915 to be conducted separately but in close proximity to medical education, in a report that came to be known as the Welch-Rose Report. Nursing education was scrutinized by the Committee for the Study of Nursing Education, which yielded what was commonly called the Goldmark Report in 1923 and advocated the inclusion of university-level training for nursing.

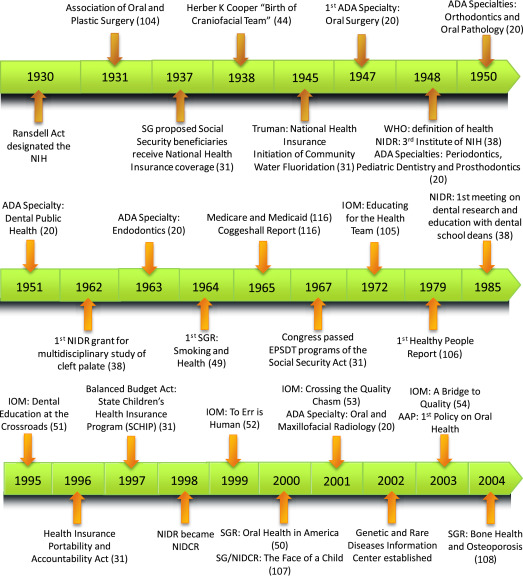

Phase 3. Mature dental education

Castiglioni in his 1941 A History of Medicine , provided medical insight into the development of dentistry. He expressed his opinion that “The bonds between dentistry and medicine are steadily becoming closer and closer.” Moreover, he saw a major contribution from dentistry in the establishment of dental clinics in schools, a significant public health achievement, made by Ernest Jessen in 1902.

During this phase, efforts to initiate National Health Insurance occurred, and selected highlights are presented here from the Medicare & Medicaid Milestones: 1937-2015 report. In 1937, the US Surgeon General proposed that Social Security beneficiaries receive National Health Insurance coverage. President Harry Truman lent support to National Health Insurance in 1945. Twenty years later, Medicare (Title XVIII) and Medicaid (Title XIX) were enacted as part of the Social Security Act in 1965. Medicare and Medicaid provided specific health services to all Americans more than 65 years of age and options for states to gain federal funds for select population groups: low-income children, their caretaker relatives, the blind, and individuals with disabilities. In 1967, Early and Periodic Screening, Diagnosis, and Treatment (EPSDT) was provided for all children on Medicaid. Fine tuning of these acts continues but the major involvement of dentistry remains with children who are Medicaid eligible. Although Federally Qualified Health Center (FQHC) became a term in 1986, clarification of this title was made with the Health Centers Consolidation Act of 1996 under Section 330 of the Public Health Service Act. The child-specific focus was present again in the Balanced Budget Act of 1997, which created the Children’s Health Insurance Program. Of these, the most clear, consistent, and comprehensive collaborative inclusion of dentistry/oral health has been through Medicaid/EPSDT. The 2013 Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) report “Keep Kids Smiling: Promoting Oral Health Through the Medicaid Benefit for Children & Adolescents,” including resources from the American Academy of Pediatrics, showed a solid ICP effort.

The first community water fluoridation (CWF) project started in 1945 and CWF became recognized among the 10 great public health achievements of the century. Perhaps an incentive for community-level prevention that had started before and was continuing during both World Wars, a leading cause of disqualification for entry to military service was failure to pass the entrance physical because of the poor condition of teeth. World War II taught the United States much about its people’s oral health status, which was poor. Missing teeth (attributed to dental caries) was the predominant reason for unfitness and rejection of entrance for military service. Hence, in 1948, the National Institute of Dental Research (NIDR) was created as the third institute of the US National Institutes of Health.

The impact of oral and general health status during times of armed conflict has been shown to be significant, for concerns ranging from the ability to consume sufficient nutrients (as simple as assurance of being able to chew rations of hard bread ) to having sufficient opposing teeth to be capable of tearing open and pulling closed weapon materials. These accounts are clearly documented from the US Civil War for the purposes of recruitment and ability to function. Statistics kept in the Civil War provided descriptive epidemiology of loss of teeth such as to prevent proper mastication, showing tooth loss variation by age, geographic location, occupation, and county of origin, and an overall 3.1% dental disqualification rate. More recent engagements showed the need to measure and address oral health status differently, such as during the Vietnam War with the implementation of the Dental Combat Effectiveness Program to reduce rates of dental emergencies, and the Army Oral Health Maintenance Program to control caries risk attributable to military life.

An orthodontist who practiced in Lancaster, Pennsylvania, studied the practice of dentistry and noted that, “in 1840 we separated the training of the dental student from that of the medical student. It seems we now try to separate the body because of that confusion in our thinking.” This thought seems to have arisen from the challenges of obtaining comprehensive care for “crippled children,” as in his expression of “the realization that although orthopedics and orthodontics are so closely related, yet in the practical application of treatment of the deformities, orthodontics and orthopedics are completely severed.” Thus, Herbert Cooper, DDS, FACD, advocated for and used in his own practice the craniofacial team. This team evolved to include surgeon, dentist, orthodontist, prosthodontist, speech therapist, pediatrician, psychologist, and social worker. He postulated that, “a team can succeed only with smooth cooperation and men who, while feeling free and independent, are willing to fit or fill a position without friction. The team needs men who can be guided without force and prompted to go ahead in the greatest interest of the patient. The only way in my opinion to have this approach work satisfactorily lies in the three c’s: communication, cooperation, and coordination of effort.” Henceforth, Dr Cooper and his work have been identified to “provide ‘best practices’ for the future of interprofessional education.”

Formal specialization in dentistry, as recognized by the ADA, started in 1947 with oral surgery. This event was followed by periodontics, pediatric dentistry, and prosthodontics in 1948; orthodontics and oral pathology in 1950; dental public health in 1951; endodontics in 1963; and oral and maxillofacial radiology in 2001.

President John F. Kennedy signed the Health Professions Educational Assistance Act of 1963, which aided both dental and medical education. The President relayed in his remarks about signing the Act: “The construction of urgently needed facilities for training physicians, dentists, nurses, and other professional health personnel can now begin. More talented but needy students will now be able to undertake the long and expensive training for careers in medicine, dentistry, and osteopathy.”

The first Surgeon General’s report (SGR) was released in 1964 and focused on smoking and health, Smoking and Health: Report of the Advisory Committee to the Surgeon General of the Public Health Service . Numerous SGRs, many focused on the ills of tobacco (more than two-thirds of the SGRs concern tobacco), have been published since ( http://www.surgeongeneral.gov/library/reports/ ). However, not until 2000 was there an SGR specifically on oral health: Oral Health in America: A Report of the Surgeon General . This SGR was compiled to convey why oral health is essential to general health and well-being.

The 1995 Institute of Medicine (IOM) report Dental Education at the Crossroads: Challenges and Change was developed in reaction to challenges in dental education, often manifested in the closing and vulnerability to closure of multiple dental schools. The committee that generated the report acknowledged 8 policy and strategic principles that give insight into perceptions of dental education at the end of the twentieth century, and these are presented in Box 1 . The committee, led by Dr. Marilyn Field, generated 22 recommendations to provide guidance for dentistry to efficiently participate in the restructuring of health care. Numerous IOM reports reflect components of the need for restructuring of health care.

- 1.

Oral health is an integral part of total health, and oral health care is an integral part of comprehensive health care, including primary care.

- 2.

The long-standing commitment of dentists and dental hygienists to prevention and primary care should remain vigorous.

- 3.

A focus on health outcomes is essential for dental professionals and dental schools.

- 4.

Dental education must be scientifically based and undertaken in an environment in which the creation and acquisition of new scientific and clinical knowledge are valued and actively pursued.

- 5.

Learning is a lifelong enterprise for dental professionals that cannot stop with the awarding of a degree or the completion of a residency program.

- 6.

A qualified dental workforce is a valuable national resource, and support for the education of this workforce must continue to come from both public and private sources.

- 7.

In recruiting students and faculty, designing and implementing the curriculum, conducting research, and providing clinical services, dental schools have a responsibility to serve all Americans, not just those who are economically advantaged and in good health.

- 8.

Efforts to reduce the wide disparities in oral health status and access to care should be a high priority for policymakers, practitioners, and educators.

Phase 4. Establishing interprofessional education for interprofessional collaborative practice

A major recent motivator for IPE/ICP has been the health care system’s changes around the drive of outcomes assessment with the Triple Aim. Box 2 provides the components and outcomes of the Triple Aim.