People with complex medical, physical, and psychological conditions are among the most underserved groups in receiving dental care and consequently have the most significant oral health disparities of any group. The traditional dental care delivery system is not able to deliver adequate services to these people with “special needs” for a variety of reasons. New systems of care are evolving that better serve the needs of these groups by using interprofessional teams to reach these individuals and integrate oral health services into social, educational, and general health systems.

Key points

- •

People with special needs are the most underserved and have the most significant oral health disparities of any group.

- •

The traditional office- and clinic-based dental care delivery system does not adequately address the oral health needs of people with special needs.

- •

There is increasing emphasis in US general health and oral health care systems on achieving the triple aim: better experiences receiving care, better health outcomes, and lower cost per capita.

- •

New delivery systems are evolving that better serve people with special needs using telehealth-connected interprofessional health care teams and creating Virtual Dental Homes.

- •

New delivery systems, with a focus on health outcomes, require and lead to integration of oral health services with social, educational, and general health systems.

Oral health and people with special needs

In proposing an expanded role for interprofessional collaborations to improve oral health for people with “special needs” it is useful to consider the definition of the phrase “people with special needs.” There are many similar terms in use in the literature. These include “people with special needs,” “children with special health care needs,” “people with disabilities,” “people with complex needs,” among others. Some of these terms, such as “children with special health care needs” or people with “developmental disabilities,” have definitions that are found in federal laws or regulations and are used for standardized data collection and reporting or for funding purposes. Other terms, such as “people with special needs,” “people with disabilities,” or “people with complex needs,” do not have generally agreed on definitions, although they are widely used and useful in describing populations who experience challenges in obtaining oral health services. For the purpose of this article the term “people with special needs” is used interchangeably with the phrases listed previously. A broad definition of this terms is people who have difficulty accessing dental treatment services because of complicated medical, physical, or psychological conditions.

People with complex medical, physical, and psychological conditions are among the most underserved groups in receiving dental care and consequently have the most significant oral health disparities of any group. In the 2000 US Surgeon General’s report Oral Health in America it was noted that although there have been gains in oral health status for the population as a whole, they have not been evenly distributed across subpopulations. That report noted that profound health disparities exist among populations including racial and ethnic minorities, individuals with disabilities, elderly individuals, individuals with complicated medical and social conditions and situations, low income populations, and those living in rural areas. These conclusions were reaffirmed in the 2011 report of the Institute of Medicine (IOM) Improving Access to Oral Health Care for Vulnerable and Underserved Populations . The IOM report noted that people with disabilities are less likely to have seen a dentist in the past year than people without disabilities; that people with intellectual disabilities are more likely to have poor oral hygiene and periodontal disease and more likely to have caries than people without intellectual disabilities; that people with special needs face systematic barriers to oral health care, such as transportation barriers (especially for those with physical disabilities) and cost; that health care professionals are not trained to work with these individuals; and that dental offices are not physically suited for them to receive care. Many other reports confirm that people with chronic medical illnesses, developmental disabilities, physical and psychosocial conditions, and the aging population in America experience more oral health care problems than others who do not have these conditions.

The Population of People with Special Needs Is Increasing Dramatically

Not only do people with special needs experience greater difficulty obtaining dental care and consequent oral health disparities, but individuals with special needs are also becoming a larger part of the population. Advances in medicine have increased the likelihood that people today live longer with comorbidities that would previously have shortened their lifespan. Forty years ago, for example, the typical person with Down syndrome would have a life expectancy of roughly 12 years compared with 60 years now. Because of these advances, the number of people with special needs who need oral health services is growing dramatically. According to the 2010 US Census, roughly 50 million people, or almost 20% of the US population, have a long standing health condition or disability. This phenomenon is increasing as the US population ages.

Challenges in Providing Oral Health Care for People with Special Needs

There are numerous challenges in providing oral health services for people with special needs that go beyond normal considerations for other populations. These challenges often require oral health professionals to have advanced training, and personal characteristics, such as empathy, patience, and desire, to be successful. There are several areas where providing oral health services for these populations presents unique challenges for dental professionals.

First there is a need to understand and to be prepared to work with people with a wide variety of general health conditions. Although oral health professionals do not need to have complete knowledge about every general health condition that their patients present with, it is essential that they have the knowledge and experience to know what information is needed, and the ability to gather and apply that information to provide appropriate services. This implies the need for training and ability to function in interprofessional health care teams and get consultations from and work with physicians, nurses, social workers, and other general and social service professionals.

There is also a need for oral health professionals to understand the social service systems that operate in their community and the social context in which oral health services take place. An understanding of the system and how to work with community living facilities, social service agencies, and advocacy organizations operating in their community is essential to success. The use of appropriate language when interacting with individuals with special needs and their caregivers is also important. There is a growing movement advocating for the use of “people first” language. This language emphasizes that disability is a part of the human condition and all people want to be described by their abilities rather than labeled by their disabilities. An oral health professional who does not understand this language and refers to people he or she treats by saying “I treat the handicapped in my practice” risks alienating the individual, their caregiver, and those advocating for full inclusion in society.

Oral health professionals also need to understand the extraordinary vulnerability of people with special needs to abuse and neglect in society. An essential skill is the ability to recognize abuse and neglect and their role as mandated reporters. Oral health providers are health professionals and as a part of the health care team they may find that their patients are depressed or struggling to cope with various living challenges. As critical members of the health care team, there is an obligation to intervene, provide basic diagnosis and counseling, and make appropriate referrals for follow-up in these situations. As integrated care becomes the norm, it is likely that these referral systems will become stronger and more readily accessible.

Oral health professionals also need to understand how to help people with special needs prevent oral diseases. There are special challenges presented by working with someone where communication and even procedures need to be performed by a third person, a caregiver. Some people have limited physical ability to perform oral hygiene procedures and “partial participation” programs need to be designed and carried out. This term refers to having the individual do as much as they are able to, and having a caregiver ensure that needed prevention procedures are completed either through additional physical aids, reminders, or direct procedures performed by the caregiver. There are numerous informational, physical, and behavioral obstacles to be addressed in preventing dental disease in special needs populations. These are described in detail in a caregiver training package titled “Overcoming Obstacles to Dental Health: A Training Package for Caregivers of Adults with Disabilities and Frail Elders.” In addition to this package, there is a large body of literature that describes the challenges and techniques for helping people with special needs prevent oral diseases.

Oral health and people with special needs

In proposing an expanded role for interprofessional collaborations to improve oral health for people with “special needs” it is useful to consider the definition of the phrase “people with special needs.” There are many similar terms in use in the literature. These include “people with special needs,” “children with special health care needs,” “people with disabilities,” “people with complex needs,” among others. Some of these terms, such as “children with special health care needs” or people with “developmental disabilities,” have definitions that are found in federal laws or regulations and are used for standardized data collection and reporting or for funding purposes. Other terms, such as “people with special needs,” “people with disabilities,” or “people with complex needs,” do not have generally agreed on definitions, although they are widely used and useful in describing populations who experience challenges in obtaining oral health services. For the purpose of this article the term “people with special needs” is used interchangeably with the phrases listed previously. A broad definition of this terms is people who have difficulty accessing dental treatment services because of complicated medical, physical, or psychological conditions.

People with complex medical, physical, and psychological conditions are among the most underserved groups in receiving dental care and consequently have the most significant oral health disparities of any group. In the 2000 US Surgeon General’s report Oral Health in America it was noted that although there have been gains in oral health status for the population as a whole, they have not been evenly distributed across subpopulations. That report noted that profound health disparities exist among populations including racial and ethnic minorities, individuals with disabilities, elderly individuals, individuals with complicated medical and social conditions and situations, low income populations, and those living in rural areas. These conclusions were reaffirmed in the 2011 report of the Institute of Medicine (IOM) Improving Access to Oral Health Care for Vulnerable and Underserved Populations . The IOM report noted that people with disabilities are less likely to have seen a dentist in the past year than people without disabilities; that people with intellectual disabilities are more likely to have poor oral hygiene and periodontal disease and more likely to have caries than people without intellectual disabilities; that people with special needs face systematic barriers to oral health care, such as transportation barriers (especially for those with physical disabilities) and cost; that health care professionals are not trained to work with these individuals; and that dental offices are not physically suited for them to receive care. Many other reports confirm that people with chronic medical illnesses, developmental disabilities, physical and psychosocial conditions, and the aging population in America experience more oral health care problems than others who do not have these conditions.

The Population of People with Special Needs Is Increasing Dramatically

Not only do people with special needs experience greater difficulty obtaining dental care and consequent oral health disparities, but individuals with special needs are also becoming a larger part of the population. Advances in medicine have increased the likelihood that people today live longer with comorbidities that would previously have shortened their lifespan. Forty years ago, for example, the typical person with Down syndrome would have a life expectancy of roughly 12 years compared with 60 years now. Because of these advances, the number of people with special needs who need oral health services is growing dramatically. According to the 2010 US Census, roughly 50 million people, or almost 20% of the US population, have a long standing health condition or disability. This phenomenon is increasing as the US population ages.

Challenges in Providing Oral Health Care for People with Special Needs

There are numerous challenges in providing oral health services for people with special needs that go beyond normal considerations for other populations. These challenges often require oral health professionals to have advanced training, and personal characteristics, such as empathy, patience, and desire, to be successful. There are several areas where providing oral health services for these populations presents unique challenges for dental professionals.

First there is a need to understand and to be prepared to work with people with a wide variety of general health conditions. Although oral health professionals do not need to have complete knowledge about every general health condition that their patients present with, it is essential that they have the knowledge and experience to know what information is needed, and the ability to gather and apply that information to provide appropriate services. This implies the need for training and ability to function in interprofessional health care teams and get consultations from and work with physicians, nurses, social workers, and other general and social service professionals.

There is also a need for oral health professionals to understand the social service systems that operate in their community and the social context in which oral health services take place. An understanding of the system and how to work with community living facilities, social service agencies, and advocacy organizations operating in their community is essential to success. The use of appropriate language when interacting with individuals with special needs and their caregivers is also important. There is a growing movement advocating for the use of “people first” language. This language emphasizes that disability is a part of the human condition and all people want to be described by their abilities rather than labeled by their disabilities. An oral health professional who does not understand this language and refers to people he or she treats by saying “I treat the handicapped in my practice” risks alienating the individual, their caregiver, and those advocating for full inclusion in society.

Oral health professionals also need to understand the extraordinary vulnerability of people with special needs to abuse and neglect in society. An essential skill is the ability to recognize abuse and neglect and their role as mandated reporters. Oral health providers are health professionals and as a part of the health care team they may find that their patients are depressed or struggling to cope with various living challenges. As critical members of the health care team, there is an obligation to intervene, provide basic diagnosis and counseling, and make appropriate referrals for follow-up in these situations. As integrated care becomes the norm, it is likely that these referral systems will become stronger and more readily accessible.

Oral health professionals also need to understand how to help people with special needs prevent oral diseases. There are special challenges presented by working with someone where communication and even procedures need to be performed by a third person, a caregiver. Some people have limited physical ability to perform oral hygiene procedures and “partial participation” programs need to be designed and carried out. This term refers to having the individual do as much as they are able to, and having a caregiver ensure that needed prevention procedures are completed either through additional physical aids, reminders, or direct procedures performed by the caregiver. There are numerous informational, physical, and behavioral obstacles to be addressed in preventing dental disease in special needs populations. These are described in detail in a caregiver training package titled “Overcoming Obstacles to Dental Health: A Training Package for Caregivers of Adults with Disabilities and Frail Elders.” In addition to this package, there is a large body of literature that describes the challenges and techniques for helping people with special needs prevent oral diseases.

The evolving dental care landscape

The US oral health industry is facing tremendous pressure to change. A large and increasing segment of the population does not access the traditional oral health care system until they have advanced disease, pain and infection. As illustrated in Table 1 , Medical Expenditures Panel Survey data indicate that most (52%) dental care in the United States is purchased by those with the top family incomes, whereas those in the bottom one-third purchase only 19% of dental services. Unfortunately, those groups in the bottom income strata, along with people with special needs as described previously, have most of the dental disease. This means that dentists are increasingly treating the wealthiest and healthiest segments of the population, whereas those with the highest rates of disease go largely untreated until they have advanced disease, pain, and infection.

| Family Income | Number (000,000) | % of Population | % with Expenses | Expenditures (000,000) | % of Expenditures |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Poor | 46.3 | 15 | 27 | $6266 | 7 |

| Near poor | 15.0 | 5 | 28 | $2321 | 3 |

| Low | 45.7 | 14 | 32 | $8333 | 9 |

| Middle | 93.4 | 30 | 39 | $27,073 | 29 |

| High | 115.2 | 37 | 54 | $47,837 | 52 |

One result of these dramatic shifts in the dental care landscape is that visits to dental offices and dentist’s incomes are decreasing. Visits to general dental offices have steadily declined, by 10% starting in 2003, well before the recent recession, and continuing well into the recovery. The American Dental Association Health Policy Resources Center has cautioned the profession not to expect a return to previous periods of increasing growth and described these declines as “the new normal.”

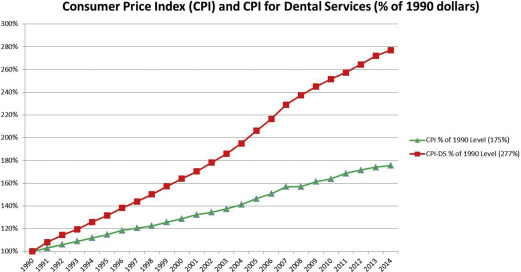

Despite decreasing demand over the last several decades, the price of dental care continues to rise during that time period. As illustrated in Fig. 1 , the Consumer Price Index for Dental Services, a marker of the average price of dental care for the average person, rose at twice the rate of the Consumer Price Index, the general rate of inflation, between 1990 and 2014. This is unfortunate because dental care is far more price sensitive than general health services. As depicted in Fig. 2 , individuals pay for dental services out-of-pocket more than they pay for any other health service except prescription drugs. High out-of-pocket costs, and increasing prices in the face of falling demand, help explain why dental care is the health service most likely to be put off by people who believe that they need care but do not obtain the care because of cost as a barrier. In addition to price, people with special needs face all the other barriers described previously.