Surgery of the temporomandibular joint (TMJ) plays a small, but important, role in the management of patients who have temporomandibular disorders (TMDs). The literature has shown that about 5% of the patients who undergo treatment for TMDs require surgical intervention . There is a spectrum of surgical procedures for the treatment of TMDs that ranges from simple arthrocentesis and lavage to more complex open joint surgical procedures. Although each surgical procedure has its enthusiastic supporters, the specific criteria for which cases are most appropriate are lacking. Unfortunately, the literature is based more on observation than on scientifically controlled studies. The success of surgery seems to be based on experience of the surgeon and appropriate case selection. It also is important to recognize that surgical treatment rarely is performed alone; generally, it is supported by nonsurgical treatment before and after surgery. In other words, surgical success is dependent on a total treatment plan that involves nonsurgical and surgical treatment. Surgery performed alone rarely has long-term success.

Each surgical procedure should have strict criteria for which cases are most appropriate. Recognizing that scientifically proven criteria are lacking, this article discusses the criteria for each procedure, ranging from arthrocentesis to complex open joint surgery. The discussion includes indications, brief descriptions of techniques, outcomes, and complications for each procedure.

Temporomandibular joint arthrocentesis

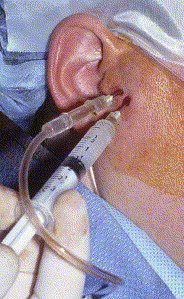

TMJ arthrocentesis is the simplest and least invasive procedure that is performed in the TMJ . Technically, arthrocentesis is not a surgical procedure; however, because it usually is discussed with surgical procedures, it is included in this article. Arthrocentesis consists of TMJ lavage, placement of medications into the joint, and examination under anesthesia. It usually is performed as an office-based procedure under local anesthesia assisted with conscious intravenous sedation, although it can be performed with local anesthesia alone ( Fig. 1 ).

The technique involves the insertion of two 18-gauge needles into the superior joint space of the TMJ under local anesthesia. Through one needle, 100 to 300 mL of Ringer’s lactate solution is injected into the superior joint space; the second needle acts as an outflow portal, which allows lavage of the joint cavity. Lysis of adhesions is achieved by intermittent distention of the joint space by momentarily blocking the outflow needle and injecting under pressure during the lavage. Steroids or sodium hyaluronate may be injected at the end of the lavage to alleviate intracapsular inflammation. Immediately upon completion of the lavage, the needles are removed and the TMJ is examined to determine freedom of movement. After recovery from the sedation, the patient is discharged. The patient is placed on a nonchew soft diet for a few days. Range of motion exercises are started immediately and continued for several days. Analgesics are prescribed as necessary for pain control.

Multiple studies have reported 70% to 90% success rates for arthrocentesis for the management of patients who have painful limited mouth opening . Arthrocentesis does seem to reduce pain and improve opening in most patients. Although its primary indication is for painful limited mouth opening, it also may be useful for other conditions that involve inflammation in the joint. The benefit of injecting medications into the joint is unclear, and yet to be proven. There have been no significant complications reported with arthrocentesis. Patients may experience temporary swelling and soreness over the joint area and a slight posterior open bite malocclusion for 12 to 24 hours after the procedure.

Arthrocentesis has become popular and may be the most common procedure that is performed in the TMJ. The advantages of arthrocentesis are that it is a simple, cost-effective, minimally invasive procedure with little morbidity that can be performed in the office.

Indications for temporomandibular joint surgery

Indications for surgery of the TMJ may be divided into relative and absolute . Absolute indications are reserved for those in which surgery has an undisputed role, such as tumors, growth anomalies, and ankylosis of the TMJ.

Because there are no objective criteria for performing TMJ surgery for the more common pain and dysfunction disorders, the decision to perform surgery should be made only after thorough evaluation of the patient. Patient selection seems to be the best determinant of surgical success. The general indications for TMJ surgery for the most common disorder—internal derangement and osteoarthrosis—are significant TMJ pain and dysfunction that are refractory to nonsurgical treatment and there is imaging evidence of disease.

Although the indications for surgery may seem to be clear, they are not specific. The first criterion, significant TMJ pain and dysfunction, may be the most important. What distinguishes the surgical candidate from patients who are not surgical candidates is localization of the pain and dysfunction to the TMJ. The more localized the pain and dysfunction to the TMJ, the better is the prognosis for a successful surgical outcome. Conversely, the more diffuse the pain and dysfunction, the less likely it is that surgical intervention will be successful. Surgical candidates should have localized continuous TMJ pain that is moderate to severe and becomes worse during jaw functions, such as chewing or talking. The pain usually is at its lowest intensity in the morning and worsens as the day progresses. Dysfunction may include painful clicking, crepitus, or locking of the TMJ. Usually, but not always, limited mouth opening is preceded by a period of painful clicking and intermittent locking.

The second criterion, refractory to nonsurgical treatment, also is nonspecific. Although nonsurgical treatment is not specified, most clinicians understand what it implies. Nonsurgical therapy should include some combination of patient education, medications, physical therapy, an occlusal appliance, and possibly, counseling. Most patients respond successfully to this treatment; therefore, surgical consideration is reserved only for patients who fail to respond successfully. The problem is that not all patients who fail nonsurgical treatment are surgical candidates. Surgical treatment is limited to those who have pain and dysfunction that arises from within the TMJ. Patients who have pain and dysfunction that arise from the masticatory muscles or other non-TMJ sources are not surgical candidates and they will be made worse by surgical intervention.

The third criterion, imaging evidence of disease, seems to be the most objective; however, imaging findings should not be interpreted in isolation. The correlation of imaging findings of disk derangement and osteoarthrosis with pain are poor . Therefore, imaging evidence should be used to confirm and support the clinical findings. The decision for surgical intervention should be made based on the clinical findings in conjunction with the impact of the pain and dysfunction on the well-being of the patient and the prognosis if no treatment is provided.

Surgical interventions include arthroscopy, condylotomy, and open joint procedures, such as disk repositioning and diskectomy. Randomized clinical trials that compare these procedures do not exist, so the surgical procedure selected is based mostly on the surgeon’s experience. Each procedure does have specific benefits as well as risks. Therefore, the procedure that has the highest potential for success with the lowest risks and most cost-effectiveness should be chosen for the patient’s specific problem. Based on the author’s experience, TMJ arthrocentesis and arthroscopy should be used for painful, limited opening; condylotomy should be used for TMJ pain with little or no restriction of opening; and open TMJ surgery should be reserved for advanced cases of TMJ internal derangement and osteoarthrosis.

Indications for temporomandibular joint surgery

Indications for surgery of the TMJ may be divided into relative and absolute . Absolute indications are reserved for those in which surgery has an undisputed role, such as tumors, growth anomalies, and ankylosis of the TMJ.

Because there are no objective criteria for performing TMJ surgery for the more common pain and dysfunction disorders, the decision to perform surgery should be made only after thorough evaluation of the patient. Patient selection seems to be the best determinant of surgical success. The general indications for TMJ surgery for the most common disorder—internal derangement and osteoarthrosis—are significant TMJ pain and dysfunction that are refractory to nonsurgical treatment and there is imaging evidence of disease.

Although the indications for surgery may seem to be clear, they are not specific. The first criterion, significant TMJ pain and dysfunction, may be the most important. What distinguishes the surgical candidate from patients who are not surgical candidates is localization of the pain and dysfunction to the TMJ. The more localized the pain and dysfunction to the TMJ, the better is the prognosis for a successful surgical outcome. Conversely, the more diffuse the pain and dysfunction, the less likely it is that surgical intervention will be successful. Surgical candidates should have localized continuous TMJ pain that is moderate to severe and becomes worse during jaw functions, such as chewing or talking. The pain usually is at its lowest intensity in the morning and worsens as the day progresses. Dysfunction may include painful clicking, crepitus, or locking of the TMJ. Usually, but not always, limited mouth opening is preceded by a period of painful clicking and intermittent locking.

The second criterion, refractory to nonsurgical treatment, also is nonspecific. Although nonsurgical treatment is not specified, most clinicians understand what it implies. Nonsurgical therapy should include some combination of patient education, medications, physical therapy, an occlusal appliance, and possibly, counseling. Most patients respond successfully to this treatment; therefore, surgical consideration is reserved only for patients who fail to respond successfully. The problem is that not all patients who fail nonsurgical treatment are surgical candidates. Surgical treatment is limited to those who have pain and dysfunction that arises from within the TMJ. Patients who have pain and dysfunction that arise from the masticatory muscles or other non-TMJ sources are not surgical candidates and they will be made worse by surgical intervention.

The third criterion, imaging evidence of disease, seems to be the most objective; however, imaging findings should not be interpreted in isolation. The correlation of imaging findings of disk derangement and osteoarthrosis with pain are poor . Therefore, imaging evidence should be used to confirm and support the clinical findings. The decision for surgical intervention should be made based on the clinical findings in conjunction with the impact of the pain and dysfunction on the well-being of the patient and the prognosis if no treatment is provided.

Surgical interventions include arthroscopy, condylotomy, and open joint procedures, such as disk repositioning and diskectomy. Randomized clinical trials that compare these procedures do not exist, so the surgical procedure selected is based mostly on the surgeon’s experience. Each procedure does have specific benefits as well as risks. Therefore, the procedure that has the highest potential for success with the lowest risks and most cost-effectiveness should be chosen for the patient’s specific problem. Based on the author’s experience, TMJ arthrocentesis and arthroscopy should be used for painful, limited opening; condylotomy should be used for TMJ pain with little or no restriction of opening; and open TMJ surgery should be reserved for advanced cases of TMJ internal derangement and osteoarthrosis.

Temporomandibular joint arthroscopy

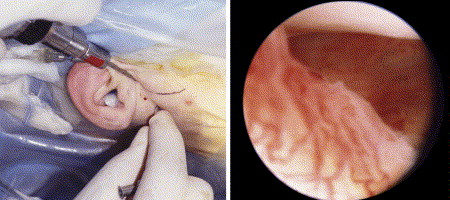

TMJ arthroscopy is a minimally invasive procedure that generally is performed under general anesthesia in the operating room. It is an equipment-dependent procedure that requires considerable manual dexterity on the part of the surgeon. TMJ arthroscopy plays a major role in the surgical management of TMJ internal derangement and osteoarthrosis.

TMJ arthroscopy involves the placement of an arthroscopic telescope (1.8–2.6 mm in diameter) into the upper joint space (UJS) of the TMJ. A camera is attached to the arthroscope to project the image onto a television monitor. The surgeon must conceptualize a three-dimensional space on a two-dimensional image. A second access instrument is placed approximately 10 to 15 mm in front of the arthroscope. The purposes of this instrument are to provide an outflow portal for irrigation and access for instrumentation of the joint space. The UJS is examined systematically starting from the posterior aspect and continuing to the anterior aspect. The examination is started posteriorly by identifying the posterior attachment tissue. The synovial lining is inspected for the presence of inflammation, such as increased capillary hyperemia. The junction of the posterior band of the disk and posterior attachment tissues can be identified ( Fig. 2 ). Movement of the joint allows for the identification of clicking or restriction in movement of the disk. As the arthroscope is moved through the UJS, the articular cartilage is inspected for the presence of degenerative changes (eg, softness, fibrillation, tears). The joint space also is inspected for the presence of adhesions, loose bodies, or other pathology. The integrity of the disk also is determined as the arthroscope is moved throughout the UJS. Perforations of the disk or posterior attachment tissues can be identified. Although the lower joint space (LJS) usually is not examined, the presence of a perforation in the disk or posterior attachment may allow limited examination of the LJS and condyle. Although sophisticated operative techniques, which range from ablation of adhesions with lasers to plication of the disk, have been developed, most surgeons limit the use of arthroscopy to lysis of adhesions and lavage of the UJS. Lysis of adhesions is accomplished most often by sweeping the arthroscope or the irrigation cannula through the adhesion and breaking it. After completion of the examination, the joint space is irrigated thoroughly to remove debris and small blood clots. Usually, the patient is discharged the same day after recovering from the anesthesia. The patient is placed on a nonchew soft diet for a few days. Range of motion exercises are started immediately and continued for several days. Analgesics are prescribed as necessary for pain control.

Multiple studies report an 80% to 90% success rate with arthroscopic lysis and lavage for the management of patients who have painful limited mouth opening . Most patients have decreased pain and improved mouth opening. Murakami and colleagues showed in studies with 5- and 10-year follow-up that arthroscopic lysis and lavage are successful for all stages of internal derangement, and that results are comparable to those obtained with open surgery procedures. Data from surgical arthroscopic techniques, such as disk repositioning, are difficult to interpret, and it is unclear that the outcomes are better than those obtained with simple lysis and lavage .

The advantages of TMJ arthroscopy are that it is minimally invasive and causes less surgical trauma to the joint. Surgical complications are rare and mostly are limited to reversible effects. Patient recovery is rapid and healing time is shorter than with open surgical procedures. The disadvantages include the surgical limitations and the necessity for sophisticated equipment.

Modified condylotomy

The modified TMJ condylotomy is the only TMJ surgical procedure that does not invade the joint structures. It is a modification of the transoral vertical ramus osteotomy that is used in orthognathic surgery. Although some investigators recommend modified condylotomy as the surgical treatment of choice for all stages of TMJ internal derangement, it seems to be most successful when used to treat painful TMJ internal derangement without reduced mouth opening . The objective of the procedure is to surgically reposition the condyle anteriorly and inferiorly beneath the displaced disk effectively by increasing the joint space between the condyle and the fossa.

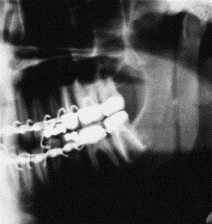

The modified condylotomy is performed under general anesthesia usually as an outpatient procedure; however, it may require an overnight stay in the hospital. An incision is made intraorally along the anterior border of the mandibular ramus. After exposure of the lateral aspect of the mandibular ramus, a vertical cut is made posteriorly to the lingula from the sigmoid notch to the mandibular angle. After mobilization of the condylar segment the medial pterygoid muscle is stripped from the segment. The mandible is immobilized using maxillomandibular fixation (MMF). Although the surgery is simple, there is a period of postoperative rehabilitation that involves 2 to 3 weeks of MMF followed by training elastics so that the occlusion is maintained ( Fig. 3 ).