Treatment of sleep apnea with mandibular advancement devices (MADs) may be associated with the development of symptoms of temporomandibular disorder (TMD). This article discusses the different types of TMD and orofacial pain problems that may occur during treatment of obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) with a MAD. It is critical that the general dentist who is providing dental devices for OSA perform a thorough physical and neurologic assessment of the temporomandibular joint and associated structures before providing such a device so that preexisting problems are identified and discussed with the patient.

Temporomandibular disorder and orofacial pain

Occasionally, treatment of sleep apnea with mandibular advancement devices (MADs) may be associated with the development of symptoms of temporomandibular disorder (TMD). The clinician needs to determine whether the problem was caused by the MAD or if the problem occurred coincidentally with use of the device. The use of the MAD may cause transient TMD symptoms when the device is first worn, but usually these symptoms resolve within a few days. For those problems that become persistent, treatment of the symptoms should be focused. This article discusses the different types of TMD/orofacial pain (OFP) problems that may occur during treatment of obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) with a MAD. It is critical that the general dentist who is providing dental devices for OSA perform a thorough physical and neurologic assessment of the temporomandibular joint (TMJ) and associated structures before providing such a device so that preexisting problems are identified and discussed with the patient.

Adverse effects of MAD s

Muscle and Joint Tenderness

Use of MADs may be associated with problems such as muscle pain or joint tenderness. Jaw tenderness is one of the most common complaints after patients start using the device. It is important to document the presence of muscle or joint tenderness before the delivery of the device. Pain problems including a headache history should be explored in the face-to-face history. The physical examination should include a neurologic examination, evaluation of jaw function, and a palpation examination of the TMJs and cervical and masticatory muscles. A common complaint of patients with OSA is morning headache. However, muscle pain and most particularly myofascial pain (MFP) are frequently associated with or cause headache. A careful palpation examination, performed as part of the initial examination, helps to document preexisting muscle pain and associated headache.

TMJ tenderness can occur with use of MADs. When an appliance holds the jaw in a protrusive position during the night, the joint may become inflamed and tender to palpation. The general term for this condition is capsulitis. Preexisting capsulitis should have been identified before delivery of the appliance, and a definitive diagnosis made at that time. Joint tenderness can be caused by macrotrauma (a sudden injury from a major force) or microtrauma (small repetitive injury) to the joint. Most frequently microtrauma is caused by excessive parafunction both during the day and while sleeping.

Joint Sounds

The presence of joint noises such as clicking or crepitus should also have been determined, diagnosed, and noted in the chart before MAD therapy. Clicking sounds may indicate anterior disk displacement with reduction, whereas crepitus indicates degenerative changes of the condyles. Anterior repositioning is often used to reduce or eliminate clicking. Using a MAD for sleep apnea or snoring may eliminate the TMJ clicking during the night, but the appliance cannot be used in the daytime and the clicking usually returns. Using repositioning appliances 24 hours per day to control or eliminate clicking causes permanent occlusal changes and should not be practiced. Longitudinal studies following clicking over extended periods of time have all shown similar outcomes (ie, the clicks do not get worse and become less of a problem or resolve completely with time). Nonpainful clicking does not need to be treated.

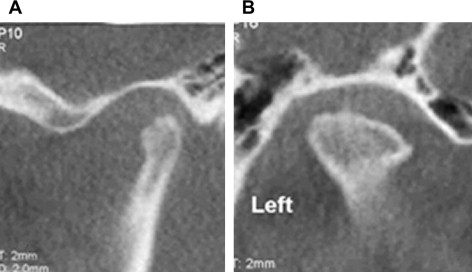

Joint crepitus (the rubbing sound heard during jaw opening and closing) is often an indication of articular surface remodeling. If the joint is tender to palpation, joint imaging, preferably cone-beam computed tomography (CBCT), should be obtained to determine if degenerative changes have occurred. The combination of crepitus, joint tenderness, and degenerative changes seen on the images is diagnostic of osteoarthritis. If the TMJs are painful at the time of the intake examination, the joint condition should be treated before placement of a MAD because the sleep appliance can aggravate the condition. The clinician should have the patient sign an informed consent form that discusses the current status of the joints and changes that can occur with the use of a MAD. A MAD should be delivered only if the condyles are stable as determined on examination and by palpation and radiographs. Areas of active condylar resorption with pain (eg, osteoarthritis) countermand use of a MAD until the joint inflammation is resolved.

Bite Changes

Bite changes have been reported in patients using MADs. Commonly, temporary occlusal changes are observed in the morning when the device is removed, requiring the patient to perform some exercises to bring the posterior teeth back together. However, evidence is mounting that long-term use of MADs causes permanent changes in the occlusal relationship. Although patients are given instructions regarding the necessity of performing exercises to bring the posterior teeth back into contact, patients may not perform the exercises as directed and the bite changes can become permanent. Changes in the relationship of the maxilla to the mandible have also been documented. These changes represent a gross shift in the jaw relationship in patients with initial class II malocclusions involving a maxillary overjet, or in class III malocclusions in which the anterior incisors are in an edge-to-edge relationship with no maxillary teeth interference with protrusion beyond the edge-to-edge relationship. Although dentofacial and occlusal changes can be attributed to use of an MAD, a recent report shows that long-term use of the CPAP (continuous positive airway pressure) mask without a MAD can also cause dentofacial changes.

Epidemiology of TMD Symptoms and Bite Changes Associated with MAD Use

Increased occurrences of TMD symptoms are not generally associated with use of MADs in the treatment of OSA. However, Clark and colleagues reported a prevalence estimate of between 10% and 13% of patients using a MAD who developed TMD symptoms that prevented use of the appliance. In addition, it has been reported that the changes became irreversible in 10% of patients using a MAD.

Classification of TMD/OFP

Dentists treating snoring and OSA should be familiar with the classification of TMDs and know how to diagnose and treat these problems when they occur. TMDs are broken down into 3 general categories: masticatory muscle disorders, TMJ articular disorders, and inflammatory disorders. The status of the TMJs and musculature must be determined before treatment of OSA with a MAD. The following sections describe the evaluation, diagnosis, and treatment of these disorders.

Masticatory Muscle Disorders

Myalgia

Myalgia is described as a dull, aching, and continuous pain associated with muscle function. The subjective description of the disorder is then confirmed by palpation of the muscles and looking for replication of the pain complaint. If the palpation-induced pain spreads to sites remote from the normal neurosensory distribution of the muscle area, this indicates MFP and not simply myalgia.

MFP

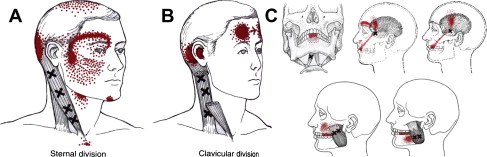

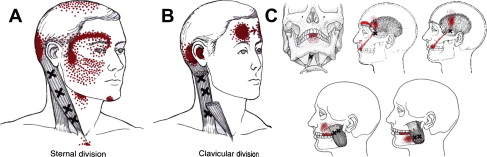

Orofacial MFP has been described in the literature. MFP is defined as muscle pain associated with active or latent trigger points that radiate pain to remote sites such as adjacent muscle groups or nonmuscle structures such as the TMJs, sinuses, or teeth. In performing a differential diagnosis for OFP of unclear origin, the clinician should palpate all of the muscle groups that can potentially refer into the area of the pain complaint to see if the source of the pain is coming from the active or latent trigger point. MFP is the great imitator of other painful conditions. The MFP trigger points may also be associated with autonomic features that could confuse and mislead the unwary clinician into thinking the pain was caused by another problem such as neuropathy, dental pain, or a neurovascular disorder when the source of the pain was muscle. Fig. 1 shows known trigger points in the orofacial and cervical regions that refer pain into the teeth and head.

A clinical examination is accomplished by a thorough muscle palpation of the masticatory and cervical muscle to evaluate for muscle pain. If the patient has muscle pain, finger pressure on the individual muscles causes pain (myalgia) and may generate a referral of pain, as shown in Fig. 1 . MFP is typically described as continuous, aching, and variable in intensity. MFP can be confirmed by injecting 0.5% procaine or lidocaine without epinephrine into the trigger point or by using ethyl chloride spray while stretching the involved muscle. The pain should decrease by at least 50% to confirm the diagnosis of MFP. Myalgia does not refer remotely.

Muscle trismus

Muscle trismus or splinting is a protective mechanism that occurs when the muscle fibers shorten and become painful as a protective mechanism limiting movement, or because of trauma. The pain and shortening of the muscle generally avoid repeated trauma. Masticatory muscle splinting is associated with limitation of range of motion and rigidity of the jaw when manipulated. Trismus may be induced as a hysterical reaction caused by psychological distress associated with the pain. Protective splinting is not associated with muscle contraction and increased electromyographic activity when the affected muscle is at rest; consequently, the muscle becomes painful only with function, and splinting increases with stretching of the muscle.

Myositis

Myositis is an inflammatory disorder of muscle caused by infection or trauma within the muscle tissue or by a noninfectious process induced by systemic disease such as polymyositis. Affected pain fibers in the muscles release inflammatory mediators (eg, substance P and calcitonin gene-related peptide [CGRP]), causing the classic signs of inflammation (ie, rubor, dolor, calor, tumor). Characteristically, the myositic muscle is tender to light touch (allodynia), palpation, and functional movement, and, in addition, signs of classic inflammation such as redness and swelling are evident. By comparison, myalgia and MFP are not usually associated with swelling and redness, although pain is induced by palpation and jaw function. Furthermore, in myositis, the inflammation is generalized and the entire muscle is usually affected. In myositis, an increased sedimentation rate is expected, but not in myalgia.

TMJ Articular Disorders

Disk derangements are common in the general population, with prevalence estimates ranging from 40% to 75% of the population. Major trauma also may damage the disk or ligaments (eg, fight, fall, sports injury, oral surgery, or motor vehicle accident), causing the disk to become displaced. Excessive parafunctional activity, such as gum chewing, bruxism, bracing, or clenching, can cause condylar remodeling due to the microtrauma from these parafunctional activities. These behaviors are believed to produce repetitive strain of the joint tissues. In addition, generalized disk ligament laxity may allow the disk to slip forward, leading to disk clicking. Furthermore, disk noises may be an early manifestation of the changes seen in a developing systemic arthritic disease process, altering the condylar form and allowing disk slippage.

The TMD mechanical problems are subcategorized as follows:

- 1.

Disk displacement with reduction: the joint clicks

- 2.

Disk displacement without reduction (close lock): the joint used to click but is now silent

- 3.

Open dislocation

- 4.

Open lock

- 5.

Posterior disk displacement

- 6.

Ankylosis.

Clicking joints

Historically, TMJ clicking was treated with full-time use of an anterior repositioning appliance in an attempt to reduce the anteriorly displaced disk. Although this treatment is still advocated, more recent longitudinal studies suggest that the clicking eventually returns. Further, studies have thrown into doubt the theory that the disk was recaptured. However, a subsequent magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) study showed that the displaced disk was not reduced, although the clicking was eliminated. Another study comparing repositioning appliances with flat-plane stabilization appliances for treatment of disk displacements concluded that the repositioning appliance was no better than the stabilization appliances as a treatment option for disk displacement. Treatment of clicking joints is not advocated unless severe pain and dysfunction are associated with the dislocation. In painful clicking and joint dysfunction, the clinician may need to consider fabricating an anterior advancement splint for nighttime use until joint inflammation subsides and the joint adapts to the mechanical dysfunction. Use of a MAD sleep appliance can provide this kind of stabilization. Most anteriorly displaced disks do not cause pain and do not need to be treated. We do not fully understand why disk slippage occurs but condylar remodeling or stress-induced alterations of the fibrocartilage lining of the joint may predispose the disk to slip forward and occasionally cause pain. In addition, clicks in the joint may not indicate displacement but can be caused by tears or injury to the disk. Joint noises may also be caused by a stick-slip phenomenon, in which the articular surface of the joint is inadequately lubricated, causing the disk to briefly stick to the anterior surface of the eminence. Evidence has accumulated showing that most clicks do not progress to locking, so MRI is not necessary since it would not substantially alter the treatment approach used. In the presence of pain and increased sticking of the disk, CT imaging of the joints should be obtained as part of the diagnostic workup before initiating any joint procedures such as steroid injections or mandibular repositioning.

Locking joints

If the joint is locking and painful, the patient should be referred to a specialist for treatment. The locked joint may need to be manipulated under local anesthetic or an arthrocentesis or lysis and lavage performed to relieve the condition. Stabilization or repositioning appliances may be used after the joint has been unlocked, but these devices cannot be expected to change the status of the lock without some type of joint procedure to remobilize the joint. After a joint procedure, a repositioning appliance may need to be used full time for 1 to 2 weeks to stabilize the joint, allow the inflammation to subside, and discourage the disk from slipping and relocking. This is a short-term expedient and long-term 24-hour-per-day use of this type of splint should be limited because it may cause permanent bite changes.

Inflammatory Joint Disorders

Although several monoarthritic and polyarthritic conditions can affect the TMJs, this article focuses only on the most likely conditions to be confronted by a general dentist who is treating OSA (ie, capsulitis, osteoarthritis, and rheumatoid arthritis). TMJ arthritis is not a unified disorder. Several inflammatory conditions can affect the TMJ but many are obscure and not often seen; however, most show overlapping clinical symptoms. The diagnosis of many inflammatory joint disorders is made based on the clinical signs and radiological and laboratory findings. However, most TMJ arthritis seen in a clinical setting is degenerative or osteoarthritic in nature and is not reflective of systemic disease. The diagnosis of osteoarthritis is made from the history, clinical signs, and symptoms rather than from laboratory findings. The TMJ apparatus, including disk function, is susceptible to arthritic changes, and pain may precede the degenerative changes.

Arthralgia/capsulitis

Inflammatory conditions of the TMJs are categorized as localized arthralgia (capsulitis), localized arthritis, and polyarthritis involving the TMJs. Localized and specific joint pain or tenderness is called arthralgia or capsulitis. These terms are used after tenderness has been confirmed with palpation. Arthralgia is used to describe palpable joint pain with no evidence of crepitus or osseous changes on the radiographs. The terms retrodiscitis or synovitis are occasionally used when the dorsal aspect of the TMJ capsule is tender to palpation, but these terms imply a diagnosis that can be made only through biopsy evaluation of the tissue.

The most important cause of arthralgia is trauma, either from external injury or traumatic parafunction. Trauma induces a local inflammation in the joint that is associated with inflammatory mediators released into the joint space. The mediators cause sensitization of the joint nociceptors, joint swelling, warmth, and pain. The inflammatory response causes alterations of the soft and hard tissues in the joint, leading to bony remodeling. Other causes of joint pain may be infection or a localized manifestation of a polyarthritic disorder.

Trauma may induce arthritis when the intra-articular soft tissues are compressed from trauma. The mandible may deviate to the side of the injury in the intercuspal position as a result of damage to the joint structure, muscle guarding, or swelling of the involved joint. The opening is restricted by inflammation in the joint and by guarding and trismus of the masticatory muscles. This situation often causes a shift in muscle-guided closing and opening positions of the jaw. If the joint is edematous, there may be no tooth-to-tooth contacts on the ipsilateral side.

The pain is described as aching in the preauricular area and often in the ear itself. It is aggravated by jaw function such as chewing, talking, opening wide, and lateral movements of the jaw. Palpation of the lateral and dorsal capsules of the joints replicates the pain. In addition, pain is caused by manually loading the joint, pushing the condyle up and back in the fossa, or by having the patient bite on a tongue blade placed between the posterior teeth on the opposite side. Wearing a MAD may cause capsulitis in some patients, particularly when the appliance is removed in the morning and the patient clenches the jaw to bring the posterior teeth into contact. Because capsulitis represents a localized inflammation of the capsule and retrodiscal tissues, the condition needs to be treated to lessen the likelihood that the continuation of joint inflammation leads to degenerative joint changes. Capsulitis is not seen with radiographic examination unless it is severe and associated with inflammatory mediated joint effusion. Excessive loading of the joints is associated with free radical production and release of inflammatory neuropeptides such as substance P and CGRP, which cause neurogenic inflammation and swelling in the joints. This process leads to breakdown of the TMJ and osteoarthritis.

Osteoarthritis

As mentioned earlier, TMJ osteoarthritis is one of the most common joint problems seen in the population that is being treated for OSA with a dental device. The prevalence of osteoarthritis increases with age, and this is the same age group in which the prevalence of OSA is more likely to occur. Osteoarthritis of the TMJ may be limited to 1 joint (monoarticular) or both (diarticular). The monoarticular form is more likely a result of trauma to the joint, whereas bilateral changes are more often caused by systemic factors or traumatic parafunctional activity. In addition, a previous nonreducing disk displacement may lead to degenerative changes in the affected joint.

The criteria for making a diagnosis of osteoarthritis are (1) palpable joint pain, (2) crepitus, and (3) radiological evidence of joint degeneration. Most arthritic TMJs have crepitant noises with joint movement. The presence of osteoarthritis needs to be ascertained in the initial examination. In addition, degenerative changes and crepitus may be present without pain. The degenerative changes could make the TMJ more susceptible to abnormal stresses with the use of a MAD.

If no pain is found on palpation of the joints but crepitus is present, or if the joint is palpably tender and crepitant, further evaluation with joint radiographs is warranted. Usually, TMJ osteoarthritis does not manifest swelling or redness because the magnitude of any inflammation is small when compared with the systemic autoimmune inflammatory disorders. Nevertheless, an acute inflammation of an arthritic joint may be associated with swelling and subsequent loss of posterior occlusal contacts on the side of the swelling. Once the joint has been treated appropriately, the occlusal contacts normalize.

There are 2 major types of traumatic injuries that induce local osteoarthritis: macrotrauma, which is caused by an external sharp force against the jaw and microtrauma as a result of repeated parafunctional activity. Another less recognized form of trauma leading to TMJ osteoarthritis under conditions of normal function occurs when a patient has had a previous disk derangement (displacement without reduction), causing joint degeneration probably as a result of loss of the disk, the shock absorber of the joint. As discussed earlier for capsulitis, the neurogenic inflammatory process related to pain and swelling in the TMJ also leads to both soft tissue and bony degeneration of the TMJs.

There are no biologic markers for osteoarthritis that can be determined in laboratory tests, so, as noted earlier, the diagnosis relies on palpation to confirm the pain is of joint origin, auscultation of joint noises, and radiographs (CBCT) ( Fig. 2 ) of the TMJ and other joints to confirm if the arthritic remodeling process is present.

Rheumatoid arthritis

Rheumatoid arthritis is an autoimmune disorder that causes the destruction of the patient’s own tissues. It starts as an inflammatory soft tissue disease, which may not show radiographic evidence of bony degeneration until the later stages of the disease. This form of arthritis is not as common as osteoarthritis but is seen frequently in older patients, who also may have OSA. The antigenic trigger of rheumatoid arthritis is the synovial tissues and not the articular surface of joint, but as the destruction of the synovia progresses, the entire joint is affected. Typically, rheumatoid arthritis in the TMJ is also accompanied by pain in other joints, and the older patient may present with joint disfigurement. Rheumatoid patients present with restricted opening and a progressive anterior open bite. The patient should be under the care of a rheumatologist and a referral should be made if the disease is suspected. Use of a MAD for sleep apnea is problematic because the forces of the appliance could adversely affect the joint. Laboratory tests are performed to look for positive rheumatoid factor (RF) or anti-CCP (anticyclic citrullinated peptide antibody). These tests are positive in 70% of rheumatoid patients but if the RF factor is positive, the anti-CCP test does not give any additional useful information.

Adverse effects of MAD s

Muscle and Joint Tenderness

Use of MADs may be associated with problems such as muscle pain or joint tenderness. Jaw tenderness is one of the most common complaints after patients start using the device. It is important to document the presence of muscle or joint tenderness before the delivery of the device. Pain problems including a headache history should be explored in the face-to-face history. The physical examination should include a neurologic examination, evaluation of jaw function, and a palpation examination of the TMJs and cervical and masticatory muscles. A common complaint of patients with OSA is morning headache. However, muscle pain and most particularly myofascial pain (MFP) are frequently associated with or cause headache. A careful palpation examination, performed as part of the initial examination, helps to document preexisting muscle pain and associated headache.

TMJ tenderness can occur with use of MADs. When an appliance holds the jaw in a protrusive position during the night, the joint may become inflamed and tender to palpation. The general term for this condition is capsulitis. Preexisting capsulitis should have been identified before delivery of the appliance, and a definitive diagnosis made at that time. Joint tenderness can be caused by macrotrauma (a sudden injury from a major force) or microtrauma (small repetitive injury) to the joint. Most frequently microtrauma is caused by excessive parafunction both during the day and while sleeping.

Joint Sounds

The presence of joint noises such as clicking or crepitus should also have been determined, diagnosed, and noted in the chart before MAD therapy. Clicking sounds may indicate anterior disk displacement with reduction, whereas crepitus indicates degenerative changes of the condyles. Anterior repositioning is often used to reduce or eliminate clicking. Using a MAD for sleep apnea or snoring may eliminate the TMJ clicking during the night, but the appliance cannot be used in the daytime and the clicking usually returns. Using repositioning appliances 24 hours per day to control or eliminate clicking causes permanent occlusal changes and should not be practiced. Longitudinal studies following clicking over extended periods of time have all shown similar outcomes (ie, the clicks do not get worse and become less of a problem or resolve completely with time). Nonpainful clicking does not need to be treated.

Joint crepitus (the rubbing sound heard during jaw opening and closing) is often an indication of articular surface remodeling. If the joint is tender to palpation, joint imaging, preferably cone-beam computed tomography (CBCT), should be obtained to determine if degenerative changes have occurred. The combination of crepitus, joint tenderness, and degenerative changes seen on the images is diagnostic of osteoarthritis. If the TMJs are painful at the time of the intake examination, the joint condition should be treated before placement of a MAD because the sleep appliance can aggravate the condition. The clinician should have the patient sign an informed consent form that discusses the current status of the joints and changes that can occur with the use of a MAD. A MAD should be delivered only if the condyles are stable as determined on examination and by palpation and radiographs. Areas of active condylar resorption with pain (eg, osteoarthritis) countermand use of a MAD until the joint inflammation is resolved.

Bite Changes

Bite changes have been reported in patients using MADs. Commonly, temporary occlusal changes are observed in the morning when the device is removed, requiring the patient to perform some exercises to bring the posterior teeth back together. However, evidence is mounting that long-term use of MADs causes permanent changes in the occlusal relationship. Although patients are given instructions regarding the necessity of performing exercises to bring the posterior teeth back into contact, patients may not perform the exercises as directed and the bite changes can become permanent. Changes in the relationship of the maxilla to the mandible have also been documented. These changes represent a gross shift in the jaw relationship in patients with initial class II malocclusions involving a maxillary overjet, or in class III malocclusions in which the anterior incisors are in an edge-to-edge relationship with no maxillary teeth interference with protrusion beyond the edge-to-edge relationship. Although dentofacial and occlusal changes can be attributed to use of an MAD, a recent report shows that long-term use of the CPAP (continuous positive airway pressure) mask without a MAD can also cause dentofacial changes.

Epidemiology of TMD Symptoms and Bite Changes Associated with MAD Use

Increased occurrences of TMD symptoms are not generally associated with use of MADs in the treatment of OSA. However, Clark and colleagues reported a prevalence estimate of between 10% and 13% of patients using a MAD who developed TMD symptoms that prevented use of the appliance. In addition, it has been reported that the changes became irreversible in 10% of patients using a MAD.

Classification of TMD/OFP

Dentists treating snoring and OSA should be familiar with the classification of TMDs and know how to diagnose and treat these problems when they occur. TMDs are broken down into 3 general categories: masticatory muscle disorders, TMJ articular disorders, and inflammatory disorders. The status of the TMJs and musculature must be determined before treatment of OSA with a MAD. The following sections describe the evaluation, diagnosis, and treatment of these disorders.

Masticatory Muscle Disorders

Myalgia

Myalgia is described as a dull, aching, and continuous pain associated with muscle function. The subjective description of the disorder is then confirmed by palpation of the muscles and looking for replication of the pain complaint. If the palpation-induced pain spreads to sites remote from the normal neurosensory distribution of the muscle area, this indicates MFP and not simply myalgia.

MFP

Orofacial MFP has been described in the literature. MFP is defined as muscle pain associated with active or latent trigger points that radiate pain to remote sites such as adjacent muscle groups or nonmuscle structures such as the TMJs, sinuses, or teeth. In performing a differential diagnosis for OFP of unclear origin, the clinician should palpate all of the muscle groups that can potentially refer into the area of the pain complaint to see if the source of the pain is coming from the active or latent trigger point. MFP is the great imitator of other painful conditions. The MFP trigger points may also be associated with autonomic features that could confuse and mislead the unwary clinician into thinking the pain was caused by another problem such as neuropathy, dental pain, or a neurovascular disorder when the source of the pain was muscle. Fig. 1 shows known trigger points in the orofacial and cervical regions that refer pain into the teeth and head.