Material and methods

Articles regarding corticotomy-facilitated orthodontics or dental distraction in healthy adolescent or adult patients without craniofacial anomalies or periodontal disease were considered. Randomized controlled trials (RCT), controlled clinical trials (CCT), and case series (CS) with sample sizes of 5 or more patients were eligible for inclusion in this review. Publications on segmental osteotomies and surgically assisted rapid maxillary expansion were not taken into account. Studies needed to focus on the velocity of tooth movement or treatment time reduction, tissue health or complications, or comparisons between different surgical techniques to be included. Mere descriptions of techniques or protocols were rejected. Only full-length articles were considered. There were no predetermined restrictions on language, publication year, publication status, initial malocclusion, or indication for treatment.

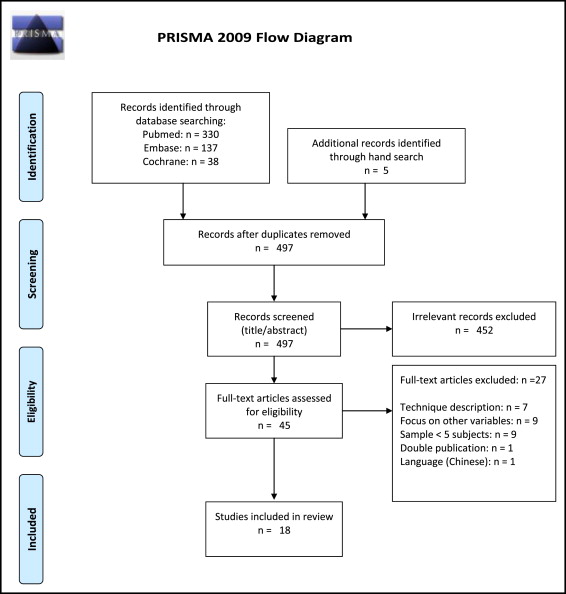

The PubMed, Embase, and Cochrane databases were searched for literature published until April 2013 using the following keywords in all fields: surg* assisted tooth movement, rapid tooth movement, corticotomy AND orthodontics, corticotomy-facilitated orthodontics, accelerated tooth movement, (piezosurgery OR piezocision) AND orthodontics, regional accelerated phenomenon AND orthodontics, RAP AND orthodontics, accelerated osteogenic orthodontics. The results were limited to human studies. To complete the search, reference lists of the included studies were manually checked.

The studies were assessed for eligibility and graded by 2 observers (E.J.H. and Y.R.). First, the hits by the search engines were screened for relevance based on title and abstract. Publications that were not related to our topic or clearly did not meet the required research designs were excluded. All relevant publications and all studies with abstracts providing insufficient information to justify a decision on exclusion were obtained in full text. If electronic articles were unavailable, the authors were contacted. The 2 observers applied the inclusion criteria separately. In case of disagreement, a consensus decision was made. Data extraction tables were used to collect and present findings from the included studies. The type of surgical intervention, the number of subjects, the tooth type, internal or external control group, the orthodontic force system used and the frequency of adjustments, the latency between surgery and orthodontic activation, the rate of tooth movement and the reduction in treatment time (if stated), and the incidence of complications (tooth vitality loss, periodontal problems, or root resorption) were extracted.

A 3-point grading system, as described by the Swedish Council on Technology Assessment in Health Care and the Centre for Reviews and Disseminations (York), was used to rate the methodologic quality of the articles ( Table I ). This tool was also used to assess the level of evidence for the conclusions of this review. Furthermore, for RCTs and CCTs (potentially producing moderate-to-strong levels of evidence), the Cochrane Collaboration’s tool for assessing risk of bias was used. Case series without controls were not assessed with this tool because the risk of bias is inherently high with such study designs.

Results

The search results are depicted in a flowchart ( Fig 2 ); 505 studies were identified in the electronic databases, and 5 additional ones were found by hand searching of the reference lists. After exclusion of irrelevant titles and abstracts, 45 full-text articles were assessed for eligibility. One study on PDL retraction published in Chinese was excluded based on language. Application of the inclusion criteria resulted in 19 eligible publications. Two studies appeared to contain overlapping data ; only the study with a control group was selected. Finally, 18 studies were included in the review.

There was complete interrater consensus on the literature selection process and grading of the publications. The design and grading of the publications are presented in Table II . The data extracted from the studies are presented in Table III . Four RCTs (3 with a split-mouth design) and 3 CCTs could be included. These studies were graded as having a moderate value of evidence (B) because reliability and reproducibility of the diagnostic tools were not described, and outcome assessment was not blinded in 6 of the 7. All other studies were case series without a control group and were therefore graded as having a low value of evidence (C). All clinical trials were judged to have certain risks of bias, as specified in Table IV . The combined number of patients treated with surgically facilitated orthodontics in the included studies was 286 (distraction procedures, n = 203; corticotomy procedures, n = 83). In only 1 article, bone augmentation was incorporated in the corticotomy procedure (n = 10).

| Grade of publication | Criteria |

|---|---|

| A: High value of evidence | All criteria should be met: |

| RCT or prospective study with a well-defined control group | |

| Defined diagnosis and end points | |

| Diagnostic reliability tests and reproducibility tests described | |

| Blinded outcome assessment | |

| B: Moderate value of evidence | All criteria should be met: |

| Clinical trial, cohort study, or case series | |

| Defined control or reference group | |

| Defined diagnosis and end points | |

| C: Low value of evidence | One or more of the following conditions: |

| Lack of a control group | |

| Large attrition of the sample | |

| Unclear diagnosis and end points | |

| Poorly defined patient material |

| Level of scientific support | Definition |

|---|---|

| Strong | At least 2 studies with high value of evidence |

| Moderate | One study with high and at least 2 with moderate value of evidence |

| Limited | At least 2 studies with moderate value of evidence |

| Inconclusive | Fewer than 2 studies with moderate value of evidence |

| Study | Design | Defined diagnosis and endpoints | Diagnostic reliability/reproducibility tests described | Blind | Grade | Duration of experiment/follow-up |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Shoreiba et al 2012 | RCT | Yes; mean grey value of alveolar bone, measured on periapical x-rays with special software, was used to quantify bone density. Root length measured on periapical x-rays from cementoenamel junction to apex to assess root resorption. Periodontal health assessed by probing depth. Data recorded at pretreatment, at debracketing, and 6 months into retention. End point: finished orthodontic treatment. | No | No | B | 3.5-5 months treatment duration/6 months retention |

| Mowafy and Zaher 2012 | RCT, split mouth | Yes; displacement of canines and first molars related to palatal rugae, digitally measured (twice) on scanned images of the plaster models. Tipping of teeth measured on panoramic x-rays, using a horizontal line through the orbital fossae as reference. End point: full canine retraction. | Partially | No | B | 1-11 months canine retraction/not specified |

| Aboul-Ela et al 2011 | RCT, split mouth | Yes; periodontal health assessed by plaque index, gingival index, probing depth, attachment level, and gingival recession pretreatment, and after 4 months of canine retraction. Tooth displacement measured monthly on plaster models. End point: 4 months of canine retraction. | No | No | B | 4 months of canine retraction/not specified |

| Fischer 2007 | RCT, split mouth | Yes; distance from tip of impacted canine to its final position in the arch was measured on plaster casts 2 weeks after surgical exposure. Time required to bring the canine tip to its correct position was recorded (in weeks), and velocity of tooth movement was calculated. Periodontal health was assessed by probing once canines were in their final resting positions. Periapical x-rays taken 1 year posttreatment to compare bone levels. End points: tips of both canines in proper position, 12 months of retention. | No | Yes, single | B | 10-20 months to align canines/12 months retention |

| Shoreiba et al 2012 | CCT | Yes; mean grey value of alveolar bone, measured on periapical x-rays using special software, was used to quantify bone density. Root length measured on periapical x-rays from cementoenamel junction to apex to assess root resorption. Periodontal health assessed by probing depth. Data recorded at pretreatment, at debracketing, and 6 months into retention. End point: finished orthodontic treatment. | No | No | B | 4-12 months treatment duration/6 months retention |

| Kharkar et al 2010 | CCT, split mouth | Yes; root resorption assessed on periapical x-rays after 6 days, full canine retraction, 1, 3, and 6 months. Displacement and tipping of canines and molars measured on lateral cephalograms after canine retraction and after 3 months. Electric pulp test pretreatment, after removal of distractors, 6 and 12 months. End points: end of canine retraction, 3, 6, and 12 months after distraction. | No | No | B | 2-3 weeks canine retraction/12 months after distraction |

| Gantes et al 1990 | CCT | Yes; periodontal health assessed by plaque scores, probing depth, probing attachment level (electronic probe, measured to the nearest 0.5 mm). Measurements for vitality/root resorption unclear or not stated. End point: finished orthodontic treatment. | No | No | B | 15-28 months treatment duration/not specified |

| Hernandez-Alfaro and Guijarro-Martinez 2012 | CS | Unclear: pulp vitality and probing depth evaluated at least once per month. Bone levels and root resorption assessed radiographically during 12-month follow-up. Methods not stated. End points unclear. | No | No | C | Unclear/12 months |

| Kisnisci and Iseri 2011 | CS | Yes; root resorption assessed on periapical and panoramic x-rays using scale (4 categories). Thermal and electric pulp tests. Timing of data collection not clearly stated. End points unclear, retrospective case selection. | No | No | C | 1-2 weeks distraction/6 months after distraction |

| Bertossi et al 2011 | CS | Unclear diagnosis and methods. Postoperative follow-up examinations at 3, 4, 7, and 30 days, and then every 2 weeks for 2 months. Pain, edema, and pocket depth assessed. Tooth sensitivity evaluated by thermal test (ice). End point: finished orthodontic treatment. | No | No | C | 1-5 months treatment duration/not specified |

| Akay et al 2009 | CS | Intrusion of premolars and molars measured on lateral cephalograms. Root resorption assessed on panoramic x-rays, but method unclear. End points not clearly stated (intrusion took 12-15 weeks). | No | No | C | 12-15 weeks intrusion, total treatment duration unclear/not specified |

| Kumar et al 2009 | CS | Yes; displacement and tipping of canines and molars measured on lateral cephalograms and panoramic x-rays before and after complete canine retraction. Apical and lateral root resorption assessed on periapical x-rays directly, 1 and 6 months after canine retraction using scale (4 categories). Electric pulp test immediately after distraction, and after 1 and 6 months. End points: complete canine retraction, 6 months after distraction. | No | No | C | 3 weeks canine retraction/6 months after distraction |

| Sukurica et al 2007 | CS | Yes; displacement of canines and molars measured on predistraction and postdistraction plaster models using a reference grid. Tipping of canines and molars measured on panoramic x-rays using reference lines. Periodontal health assessed by probing depth (3 sites per tooth), vitality checked with electric pulp tests, and root resorption evaluated on periapical x-rays predistraction and postdistraction, and 6 months after distraction. End points: end of distraction phase, 6 months after distraction. | No | No | C | 2-4 weeks canine retraction/6 months after distraction |

| Gürgan et al 2005 | CS | Yes; periodontal health evaluated by plaque index, gingival index, pocket depth (4 sites per tooth), and width of keratinized gingiva pretreatment, directly and 1, 6, and 12 months postdistraction. Assessment of vitality and root resorption unclear. End points: 1, 6, and 12 months after canine distraction. | No | No | C | 1-2 weeks canine retraction/12 months after distraction |

| Iseri et al 2005 | CS | Yes; root resorption assessed on periapical and panoramic x-rays using scale (4 categories) predistraction and postdistraction. Vitality checked by electric pulp test. Displacement and tipping of canines and molars measured on lateral cephalograms. End point: end of canine distraction phase. | Partially | No | C | 1-2 weeks canine retraction/not specified |

| Sayin et al 2004 | CS | Yes; root resorption and bone levels were assessed on periapical x-rays pretreatment and weekly during distraction. Tooth displacement measured (caliper) intraorally, on plaster models and lateral cephalograms predistraction and postdistraction. Measurement of periodontal parameters unclear. End point: end of canine distraction phase. |

No | No | C | 3 weeks canine retraction/unclear |

| Kisnisci et al 2002 | CS | Unclear diagnosis and end points; root resorption evaluated on periapical and panoramic x-rays, vitality tests not specified. | No | No | C | 1-2 weeks canine retraction/4-11 months after distraction |

| Liou and Huang 1998 | CS | Yes; distance between canine and lateral incisor recorded intraorally with caliper every week until canine retraction was completed. Anchorage loss (molar) measured on lateral cephalograms predistraction and postdistraction. Apical and lateral root resorption assessed on periapical x-rays predistraction and postdistraction using scale (4 categories). Vitality checked with electric pulp test before and at least 1 month after distraction. End point: 3 months after canine distraction phase. | No | No | C | 3 weeks canine retraction/3 months after distraction |

| Publications on surgically facilitated dental distraction procedures | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Author/year | Intervention | #S | Tooth type | C | Force (cN) | Latency | Activation | Rate of tooth movement | Reduct | Vit loss/Perio/RR |

| Mowafy and Zaher 2012 | Periodontal ligament distraction | 30 | U3 | 1 | JS | 0 d | 1 turn/d | 5.9 ± 1.4 mm retraction in 37 ± 10 d, 10° tipping, 2.5 ± 0.9 mm AL | – | ?/?/? |

| Canine retraction with nickel-titanium coil | 30 | U3 | 1 | CS (½ of JS force) | 0 d | Continuous | 4.7 ± 1.6 mm retraction in 195 ± 47 d, 0.3° tip, 2.8 ± 1.5 mm AL | – | ?/?/? | |

| Kisnisci and Iseri 2011 | Dentoalveolar distraction | 73 | U3 | 0 | JS | 1-2 d | 0.8 mm/d | ±5 mm retraction* in 10 d (9-14 d) | 50% | No/no/no |

| Kharkar et al 2010 | Dentoalveolar distraction | 6 | U3 | 1 | JS | 2 d | 0.5 mm/d | ±5 mm retraction* in 12.5 d; 10° tipping, minimal AL | – | No/?/no |

| Periodontal ligament distraction | 6 | U3 | 1 | JS | 0 d | 0.5 mm/d | ±5 mm retraction* in 19.5 d, 15° tipping, minimal AL | – | No/?/1canine minimal RR | |

| Kumar et al 2009 | Periodontal ligament distraction | 8 | U3 | 0 | JS | 0 d | 0.5 mm/d | 5.2 mm retraction in 20 d; 15° tipping, minimal AL | – | No/?/NS |

| Sukurica et al 2007 | Dentoalveolar distraction | 8 | U3, L3 | 0 | JS | 3 d | 0.5 mm/d | 5.4 ± 1.2 mm retraction in 14.7 ± 3.5 d, 9° tipping, 1.2 ± 0.8 mm AL | – | 13canines no pulpal response/NS/NS |

| Gürgan et al 2005 | Dentoalveolar distraction | 18 | U3 | 0 | JS | 1-3 d | 0.8 mm/d | ±5 mm retraction* in 10.4 d (8-14 d), no AL | 6-9 mo/ 50% | No/no/no |

| Iseri et al 2005 | Dentoalveolar distraction | 10 | U3 | 0 | JS | 1-3 d | 0.8 mm/d | ±5 mm retraction* in 10.0 d (8-14 d), 13° tipping, minimal AL | 50% | Allc anines: no pulpal response/ ?/no |

| Sayin et al 2004 | Periodontal ligament distraction | 18 | U3, L3 | 0 | JS | 0 d | 0.75 mm/d | 5.8 mm retraction in 21 d, 12° tipping, minimal AL | 3-4 mo | ?/no/NS |

| Kisnisci et al 2002 | Dentoalveolar distraction | 11 | U3, L3 | 0 | JS | 0 d | 0.8 mm/d | ±5 mm retraction* in 8-14 d | – | No/?/no |

| Liou and Huang 1998 | Periodontal ligament distraction | 15 | U3, L3 | 0 | JS | 0 d | 0.5-1.0 mm/d | 6.5 mm retraction in 21 d, minimal tipping and AL | – | 17canines no pulpal response/?/no |

| Publications on corticotomy-facilitated orthodontics | ||||||||||

| Shoreiba et al 2012 | Buccal vertical interradicular corticotomies | 10 | L1-L3 | 2 | FA | 0 d | once/2 w | Mean treatment duration 17.5 w | 66% | ?/NS/less RR |

| Orthodontic treatment only | 10 | 2 | FA | – | Mean treatment duration 49 w | |||||

| Shoreiba et al 2012 | Buccal vertical interradicular corticotomies | 10 | L1-L3 | 2 | FA | 0 d | once/2 w | Mean treatment duration 17 w (14-20) | – | ?/NS/NS |

| Buccal interradicular corticotomies + bone augmentation | 10 | L1-L3 | 2 | FA | 0d | once/2 w | Mean treatment duration 16.7 w (14-20) | – | ?/NS/NS 26% increased bone density |

|

| Hernandez-Alfaro and Guijarro-Martinez 2012 | 3 buccal vertical interradicular corticotomies per arch with tunnel approach/piezosurgery | 9 | Full arches | 0 | FA | 1 d | – | – | – | No/no/no |

| Aboul-Ela et al 2011 | Buccal corticotomies (perforations) in the U2-U4 region and extraction of U4 | 13 | U3 | 1 | CS 150 (+FA) | 0 d | – | 1.9 mm in 30 d, 3.7 mm in 60 d, 4.8 mm in 90 d, 5.7 mm in 120 d | – | ?/NS/? |

| Extraction U4 + conventional orthodontics | 13 | U3 | 1 | CS 150 (+FA) | 0 d | – | 0.8 mm in 30 d, 1.6 mm in 60 d, 2.5 mm in 90 d, 3.4 mm in 120 d | |||

| Bertossi et al 2011 | Buccal interradicular + subapical corticotomies to extrude ankylosed teeth or accommodate arch expansion | 10 | Various | 0 | FA | 1-7 d | – | 4-5 mm extrusion of ankylosed premolars in 18-25 d; 6-8 mm maxillary expansion in 68-150 d |

65%-70% | No/no/? |

| Akay et al 2009 | Buccal and palatal vertical + subapical corticotomies to facilitate intrusion of posterior teeth to close anterior open bite | 10 | U4-7 | 0 | CS 200-300/molar 100-150/premolar + FA (segmented) |

7 d | once/3 w | 3-3.5 mm intrusion in 84-105 d | – | ?/?/NS |

| Fischer 2007 | Canine exposure + multiple cortical perforations at canine level | 6 | U3 | 1 | FA, 60 | 2 w | once/2-6 w | 10-14 mm canine movement in 266-378 d, mean 0.3 mm/w | 28%-33% | ?/NS/? |

| Conventional canine exposure | 6 | U3 | 1 | FA, 60 | 2 w | once/2-6 w | 11-15 mm canine movement in 406-546 d, mean 0.2 mm/w | |||

| Gantes et al 1990 | Buccal + lingual interradicular + subapical corticotomies | 5 | Full arches | 2 | FA | 0 d | – | Mean treatment time 14.8 mo (11-20 mo) | 50% | No/NS/NS |

| Orthodontic treatment only | 4 | Full arches | 2 | FA | – | Mean treatment time 28.3 mo (24-35 mo) | ||||

| Publication | Selection bias | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Random | Allocation | Performance | Detection | Attrition | Reporting | Other | |

| Shoreiba et al 2012 | ? | ? | ? | Low | High, 3 dropouts | ? | ? |

| Mowafy and Zaher 2012 | Low | ? | Low | High | Low | Low | ? |

| Aboul-Ela et al 2011 | Low (coin toss) | ? | Low | ? | Low (split-mouth design), 2 dropouts | ? | ? |

| Fischer 2007 | ? | ? | Low | Low | Low | ? | ? |

| Shoreiba et al 2012 | ? | ? | High | High | Low | ? | ? |

| Kharkar et al 2010 | High | ? | ? | High | Low | High | ? |

| Gantes et al 1990 | High | High | High | High | Low | Low | ? |

In general, orthodontic appliances were placed before surgery, activated immediately or shortly after surgery, and adjusted at short intervals (at least every 2 weeks with corticotomy, once or twice daily with distraction) to optimally take advantage of the temporarily (3-4 months) increased bone turnover. The amount of tooth movement was directly compared with a control group in 2 studies on corticotomy. Shortly after surgery, the rate of tooth movement was doubled; after 3 months, the acceleratory effect ceased. In both studies, the measurements were made on dental casts; Aboul-Ela et al used the palatal rugae as a reference to measure canine retraction. Fischer measured the linear distance of the palatally exposed canine tips to their planned position in the arch when orthodontic traction was started (2 weeks after surgery). The mean velocity of tooth movement was calculated once the canine crowns reached their proper position. Two other studies compared treatment duration in the corticotomy group with a control group, matched by the amount of crowding or the malocclusion. In the first study, the average time needed to finish treatment was reduced to 17.5 weeks, compared with 49 weeks in the control group. In the second study, the average treatment duration was reduced to 14.8 months, compared with 28.3 months in the control group. However, the treatment goals were not specified, and both studies lacked outcome assessments. In general, the reported reductions in total treatment time ranged from 30% to 70% among the publications on corticotomy ( Table III ).

In the premolar extraction patients, canine retraction was fully accomplished within 2 weeks with dentoalveolar distraction and within 3 to 5 weeks with PDL distraction. One study on PDLs showed that tooth movement was only significantly enhanced if a jackscrew type of appliance was used; the coil spring used in the control group resulted in much slower, but more bodily retraction. Distal tipping of the canines averaged 10° to 15° with the distraction protocols and obviously needed correction in the next phase of treatment with fixed appliances. Sayin et al estimated that the reduction in total treatment duration was 3 to 4 months with PDL distraction. Studies on dentoalveolar distraction reported 6 to 9 months or even a 50% reduction in overall treatment duration. However, no control groups were used in these studies, leaving it unclear what these calculations were based on.

All publications claimed enhanced tooth movement after surgery, but only 4 studies (all of moderate value of evidence, grade B) used a control group having conventional orthodontic treatment. Therefore, there is only a limited level of evidence supporting that surgically facilitated orthodontic treatment significantly reduces treatment duration compared with conventional orthodontic treatment.

As for complications, no clinical signs of tooth vitality loss were reported in any studies. Three studies on corticotomy-facilitated orthodontics stated that “all teeth remained vital,” but the diagnostic tools were not specified, nor were data provided. No changes in tooth sensibility were detected in 5 of the studies on dental distraction. Only 3 of these mentioned the diagnostic tool (electronic or thermal pulp test). However, in 3 other studies, several canines did not show a positive response to electronic pulp tests. The validity of this test during active orthodontic treatment was questioned because untreated neighboring teeth also tested negative in some patients. Based on these findings, the evidence regarding tooth vitality after surgically facilitated orthodontics is inconclusive.

Periodontal problems were assessed in 4 studies on distraction and in 7 studies on corticotomy-facilitated orthodontics; these studies comprised various surgical protocols with different incisions and flaps. In general, none of them resulted in detrimental effects (increased probing depth, recession, attachment loss, or bleeding on probing) on the periodontium, compared with baseline values or a control group. A small mean decrease in pocket depth after treatment (0.2-1.5 mm) was recorded in some publications. Five grade B and 2 grade C studies provide limited levels of evidence that surgically facilitated orthodontic treatment is safe for the periodontal tissues.

Root resorption was assessed in all studies on distraction and in 5 studies on corticotomy. None reported significant root shortening when compared with the control group or the pretreatment root length. In some studies, even less root resorption was observed in the corticotomy group than in the controls. Again, limited evidence supports that root resorption after surgically facilitated orthodontics does not exceed the resorption observed with conventional orthodontic treatment.

We considered the effect of the surgical protocol on the efficiency of tooth movement and complications. One study compared corticotomy with bone augmentation with corticotomy alone. Treatment duration was not influenced by the augmentation, but posttreatment bone density was significantly enhanced. Another study showed that dentoalveolar distraction facilitated slightly faster canine retraction, with less tipping than the more conservative PDL distraction. In the dentoalveolar distraction group, no root resorption was observed, and in the PDL distraction group, 1 canine had minimal root resorption. No complications that would significantly favor one technique over the other were reported in these studies.

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses