Placement of dental implants in the maxillofacial region is routine and considered safe. However, as with any surgical procedure, complications occur. Many issues that arise at surgery can be traced to the preoperative evaluation of the patient and assessment of the underlying anatomy. In this article, the authors review some common and uncommon complications that can occur during and shortly after implant placement. The emphasis of each section is on the management and prevention of complications that may occur during implant placement.

Key points

- •

Many of the issues that arise at surgery can be traced to the preoperative evaluation of the patient and assessment of the underlying anatomy.

- •

Prevention of all surgical complications is impossible; however, many can be minimized with proper planning.

- •

Failure to recognize variations in the regional anatomy of the maxilla and mandible can be the cause of major bleeding during implant placement.

- •

Consultation with restorative colleagues, computed tomography when the anatomy is in question, and a thorough review of the patient’s medical history will help.

Introduction

Any number of complications can occur during or after the placement of dental implants. Most are immediately apparent; however, some can occur much later. Most complications can be traced to treatment planning and execution and are therefore preventable. Christman and colleagues recommended the use of a safety checklist before the placement of implants; this checklist includes a review of the patient’s medical and dental history, a diagnostic workup, a determination of the periodontal stability of adjacent teeth, and effective communication with restorative partners. We agree that a thorough review of all of the patient’s records before the procedure will help to prevent some of the common complications seen during implant placement. This article reviews some of the more common and a few of the more severe surgical complications associated with the placement of implants. Additionally, we discuss short-term surgical complications, those seen either at the time of placement or during the weeks or months thereafter, with an emphasis on their management and prevention. In a few cases, the discussion also includes longer term complications related to the surgical procedure. When the material overlaps with that presented in other articles in this issue, the reader is referred to those works.

Introduction

Any number of complications can occur during or after the placement of dental implants. Most are immediately apparent; however, some can occur much later. Most complications can be traced to treatment planning and execution and are therefore preventable. Christman and colleagues recommended the use of a safety checklist before the placement of implants; this checklist includes a review of the patient’s medical and dental history, a diagnostic workup, a determination of the periodontal stability of adjacent teeth, and effective communication with restorative partners. We agree that a thorough review of all of the patient’s records before the procedure will help to prevent some of the common complications seen during implant placement. This article reviews some of the more common and a few of the more severe surgical complications associated with the placement of implants. Additionally, we discuss short-term surgical complications, those seen either at the time of placement or during the weeks or months thereafter, with an emphasis on their management and prevention. In a few cases, the discussion also includes longer term complications related to the surgical procedure. When the material overlaps with that presented in other articles in this issue, the reader is referred to those works.

Common and uncommon complications with implant placement

Bleeding

Minor bleeding is inherent during the placement of dental implants, as with any surgical procedure. However, major bleeding is uncommon and can be life threatening. The causes of major bleeding may be related to systemic issues or regional anatomy. A wide variety of systemic issues can increase bleeding in a given patient. They may be broadly divided into those related to medications and those related to an underlying bleeding coagulopathy. Although a complete discussion of the management of every type of congenital or developmental bleeding disorder is beyond the scope of this discussion, it is worth noting that many patients with coagulopathies can undergo routine dentoalveolar surgery either in an office or in a hospital environment. Perhaps the most common potential bleeding issue seen in an office setting occurs with patients who are taking warfarin. These patients can undergo implant dentistry according to the protocols developed for dentoalveolar surgery. Most guidelines suggest that patients with an International Normalized Ratio of less than 3.5 can have a simple single extraction without any adjustment in anticoagulation. For patients taking warfarin, the overall frequency of persistent bleeding (2%) is low when all dental procedures are considered. However, when extractions are combined with placement of an implant, the incidence of persistent bleeding increases to 4.8%. This suggests that patients taking warfarin are at a higher risk of postoperative bleeding after simultaneous extraction and implant placement are combined if coagulation levels are not adjusted before the procedure. When such adjustments are not possible, the extraction and implant placement can be performed as a staged procedure.

It is important to understand that many patients who require anticoagulation but do not have prosthetic heart valves may be taking a newer class of anticoagulant drugs. The mechanism of action of these newer medications is different from that of warfarin: they directly inhibit either thrombin (dabigatran) or factor Xa (apixaban and rivaroxaban). The half-life of the drugs currently on the market ranges from 9 to 28 hours. The number of patients using these medications is increasing, and bleeding in association with dentoalveolar surgery is a distinct possibility. A systematic literature review concluded that the evidence and the recommendations of published guidelines all point to the same conclusion: Oral antithrombotic medication, including dual antiplatelet therapy, should not be interrupted for simple dental procedures. Currently, there are no established protocols for managing patients taking these drugs who are undergoing dentoalveolar surgery, and the reversal of these newer medications is difficult. For these reasons, we suggest a consultation with the patient’s physician so that perioperative anticoagulation scenarios can be discussed.

Anatomic concerns

Failure to recognize variations in the regional anatomy of the maxilla and mandible can be the cause of major bleeding during implant placement. In some cases, the bleeding may have life-threatening consequences. The primary focus of the rest of this section is to review the specific anatomy of the maxilla and mandible and its relationship to cases of bleeding during and after surgery.

Maxilla

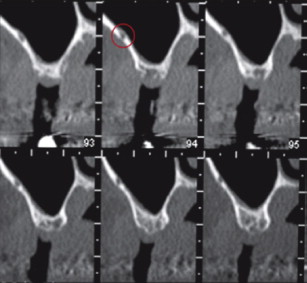

Bleeding with the placement of maxillary implants is rare. Moderate or severe maxillary bleeding may result from injury to intraosseous vessels lying within the walls of the maxilla. The vessels can be seen on computed tomography (CT), but not on plain radiographic films ( Fig. 1 ). Anterior or posterior nasal bleeding, which may be profuse, and rapid swelling of the gingiva are common signs associated with an injury to one of these vessels. Aggressive surgery is necessary when the bleeding cannot be controlled by local means. Cauterization of the bleeding site using a nasal endoscope is the most common operative technique, but if an endoscope is not available, a Caldwell-Luc procedure can be used to identify and coagulate the injured vessel. Careful evaluation of a CT of the maxilla in the areas of interest can prevent this type of maxillary bleeding during implant placement or sinus lifts.

Mandible

Multiple publications have reported bleeding, in some cases life-threatening hemorrhage, after the placement of implants in the anterior mandible. Dubois and colleagues reviewed 18 reported cases of life-threatening hemorrhage after implant surgery, most of which occurred when implants were placed in the region between the canines. Eight patients required intubation and 7 needed tracheostomies to ensure patency of the airway. Three of the 18 cases were managed by observation.

The cause of bleeding during implant placement in the anterior mandible is perforation of the lingual cortex, resulting in injury to the terminal branches of the sublingual or submental artery. The risk of perforation is high when the lingual fossa is very deep and is even higher when no flap is elevated during the procedure. One study involving 100 participants found that in 80% the depth of the submandibular fossa was more than 2 mm.

Several techniques are available for assessing potential implant sites in both the anterior and posterior regions of the mandible, including both clinical assessment and radiographic evaluation of the intended site. The results of palpation of the ridge are variable; however, during the procedure, dissection of the lingual aspect of the mandible can determine its curvature and help to prevent perforation. Examining a facial CT with attention to the lingual aspect of the mandible also alerts the surgeon to possible risks of perforation in this region.

Management of bleeding once perforation has occurred requires both control of the hemorrhage and protection of the airway. In the early stages, when hemorrhage is seen in the floor of the mouth, basic measures should be taken, including immediate bimanual compression at the suspected perforation site and control of the patient’s blood pressure if it is elevated. The injection of local anesthesia with a vasoconstrictor through the perforation may be helpful. If there is any doubt about control of bleeding, the airway should be secured in the dental office or the patient should be transported to the nearest hospital by emergency medical services so that the airway can be secured without delay. Once the airway has been secured, then isolation of the vessel(s) that has been injured can be identified. It is mandatory that the surgeon be alert for delayed hematomas on the floor of the mouth when patients complain of a protruding tongue, hemorrhage, or respiratory distress. If hemorrhage is severe, it is almost impossible to visualize the anatomy in the affected area. Retraction of the artery after laceration makes ligation difficult or impossible. If operative intervention is necessary for controlling the hemorrhage, an extraoral approach for ligation procedures is preferred. The facial and submental arteries can easily be accessed and should be ligated first. Surgical intervention for ligation of vessels is usually not necessary, but the patient may need to be intubated for several days for protection of the airway. Antibiotics should be used to prevent infection when hematomas are extensive, especially if intraoral communication is present. Administration of steroids for reducing swelling should also be considered.

Although published reports show that severe bleeding with hematoma formation is a very rare complication, the consequences of such a complication for the patient can be tremendous when the lingual cortex is perforated. We suggest that, if there is any question regarding the mandibular anatomy, a CT should be included in the planning stages for implant placement in the anterior region of the mandible.

Infection

Postoperative infections can occur after implant placement with or without grafting of the site. A variety of local and systemic factors may play a role in the development of such infection. Our review of the literature suggests an inconsistency in the definition of postoperative infection. In this section, we define postoperative infection as the presence of purulent drainage (either spontaneously or by incision) or fistula in the operative region, together with pain or tenderness, localized swelling, redness, or fever (>38°C). Early infection is defined as infection occurring within 1 week postoperatively, and late infection, as infection occurring from 1 week postoperatively to the time of abutment connection (3–8 months postoperatively).

It is believed that bacterial contamination during implant insertion can cause early failure of the dental implant. Contamination of the implant surface by bacterial biofilms during operative procedures can lead to an inflammatory process in the hard and soft tissues, thus decreasing the implant success rate. Infections around biomaterials are very difficult to treat and nearly all infected implants may fail at some time after placement.

Although massive infection after the placement of dental implants is possible, most early infections occur when grafts are used, and most of these occur with a sinus lift. We refer the reader to the article by Drs Fugazzotto and Kenney elsewhere in this issue for additional details regarding the management and prevention of infections associated with sinus lifts.

Prophylactic antibiotics

Prophylactic antibiotics may prevent postoperative infections and thus decrease implant failure. The benefit of antibiotic prophylaxis for healthy patients undergoing routine placement of dental implants is controversial. For an otherwise healthy patient, intraoperative tissue manipulation and clinical technique seem to be the most important factors in determining whether the implant site becomes infected after surgery.

Some studies have found that the use of prophylactic antibiotics of little or no benefit, whereas others have found the opposite. Those opposed to the routine use of antibiotics note that such drugs are associated with risks, including diarrhea, anaphylaxis, and antibiotic resistance with the development of resistant strains. Even those published reports that advocates the use of antibiotics do not discuss a standard regimen or protocol for their use during implant placement. A number of regimens have been suggested including preoperative single or multiple doses, postoperative single or multiple doses for several days, or a preoperative dose followed by a postoperative dose. Conceptually, when antibiotic prophylaxis is indicated an appropriate-spectrum antibiotic should be administered preoperatively as a single dose. The drug must be present at an adequate concentration in the blood stream before the incision is made, and its use should be discontinued postoperatively. A recent report illustrated this point by comparing 2 antibiotic protocols (a single dose before surgery and a 3-day course of antibiotic). The outcome assessed was the reduction of early failure of dental implant. A several-day course of antibiotics after implant placement was not shown to have an advantage over a single preoperative dose. Although the authors suggested the need for a larger sample size, they concluded that a single dose of antibiotics before implant placement is sufficient to prevent infection and implant failure.

Another study compared 4 antibiotic protocols: A single dose of amoxicillin administered preoperatively, 3 days postoperatively, 5 days postoperatively, 7 days postoperatively, and a placebo. The outcome assessed was the success of osseointegration of the dental implant in an animal model. The results of the study suggested that prolonged use of antibiotics may have a negative effect on bone formation around implants. The authors recommended a single preoperative dose of amoxicillin because it has minimal adverse effects on the host and on osseointegration.

Late infection

Actinomycosis has been implicated in a number of cases of implant failures. Actinomyces odontolyticus was present in 84% of Actinomyces -positive failed implants. Oral actinomycosis is uncommon, but it can cause infection and in some instances massive bone destruction. A published report described an implant that failed 1.5 years after placement and 3 years after tooth extraction. Radiographs revealed a large radiolucency on the mesial aspect of the implant, which was placed in the lower second bicuspid region. The implant was surgically removed, and the lesion thoroughly debrided. A course of antibiotics was prescribed. Histologic examination noted sulfur granules, which were confirmed to be actinomycotic colonies. The authors reported no recurrence of the infection 1 year after the procedure.

Fungal infection

Fungal infections after implant surgery are also rare. However, the incidence of fungal infection of the paranasal sinuses is increasing. More than 10% of all patients with chronic sinusitis have an aspergilloma, the most common type of chronic noninvasive fungal sinusitis. An unusual case of Aspergillus infection associated with dental implants and sinus bone grafting has been reported.

Successful treatment of patients with noninvasive fungal sinusitis requires surgical curettage with removal of the mycotic masses. Both a Caldwell-Luc procedure and endoscopic techniques have been used for this purpose. In general, fungal infections do not tend to recur after successful removal of mycotic masses. Systemic antifungal therapy may be required if the patient continues to exhibit symptoms after surgical treatment. Invasive and fulminant fungal sinusitis is the rarest form of fungal sinusitis and occurs primarily in immunosuppressed patients. Because fulminant fungal sinusitis may be fatal, an invasive infection requires not only aggressive surgical debridement of abnormal bone and soft tissue, but also prolonged antifungal chemotherapy.

Nerve Injury

Injuries to the inferior alveolar nerve and, less frequently, the lingual nerve have been reported and are of concern when posterior mandibular implants are placed. Management of these injuries is predicated on the degree of nerve injury. Prevention can be simplified to careful preoperative planning. The readers are referred to the article by Drs Al-Sabbagh, Okeson, Khalaf and Bertolli elsewhere in this issue for more details about the management and prevention of these injuries.

Malpositioning of Implants

Malpositioning of implants can occur during implant surgery and may be the result of a number of factors, such as the quantity or quality of residual available bone, dental inclinations adjacent to the surgical implant site, and lack of previous prosthodontic planning. Managing an implant that is poorly positioned may require a modified prosthetic attachment or surgical removal. The choice of treatment depends on the degree to which the poorly positioned implant will compromise the restorative plan. The reader is referred to the articles by Drs Kim, Sadid-Zadeh and Kutkut elsewhere in this issue.

Injury to Adjacent Teeth

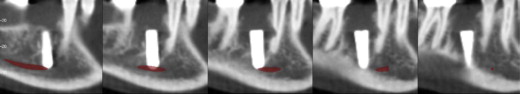

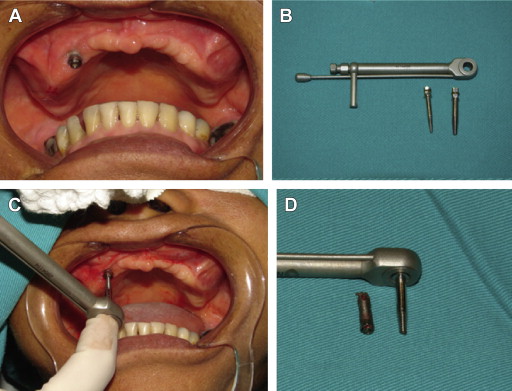

When partially edentulous patients are treated, there is a risk of direct or indirect (thermal) injury to the roots of the adjacent teeth ( Fig. 2 ). Depending on the severity of the injury, the tooth may be sensitive to cold and tender to percussion, and may cause mild discomfort when the patient is eating, although the injured tooth may respond normally to vitality tests. Treatment may involve extraction or endodontic treatment. When an implant is in direct contact with an adjacent tooth, immediate removal of the implant may avoid major complications to the tooth. In some instances, implant removal may be accomplished with counterclockwise movement. In other instances, an internal device (Implant Retrieval Tool, Nobel Biocare, Kloten, Switzerland) can be used to unscrew the implant ( Fig. 3 ).

Several published reports have described the histologic response of the periodontium, cementum, and pulp after intentional root injury created with titanium orthodontic screws. Unlike implant surgery, this protocol required insertion of the screws without the use of drills. However, the injuries were similar to those occur when implants are placed. The authors concluded that permanent damage to the pulp and supporting tissues does not routinely occur when miniscrews abrade or even enter the root surface. Immediate removal of the mini-implant leads to cementum repair, but leaving the mini-implant in place leads to either a delay in repair or no repair. Placing mini-implants less than 1 mm from the surface of the root causes root–surface resorption. Another study found that, when titanium screws penetrated cementum or dentin, no pulpal necrosis or inflammation was observed after 12 weeks. Cementum regenerated at every injury site, but ankylosis was possible when root fragmentation was present. Woven bone was seen at the screw–bone interface, even when root contact suggested osteointegration. Increased resistance is an indicator of possible root contact during implant placement.

Although these studies are interesting, prevention of injury to adjacent teeth starts with the preoperative assessment and planning of the procedure and the assessment of the amount of space available for implant placement. Surgical guides are helpful if they are well designed.

Fracture of the Mandible

Rehabilitation of a severely resorbed mandible (greatest height <7 mm) with implants is a surgical and prosthetic challenge because of the minimal amount of residual bone. Fractures can occur in less dense or poorly mineralized bone when stress or strain develops as implants are placed. Excess tightening of a screw-type implant can result in microfractures in the surrounding bone caused by the strain generated by placing the implant in unhealthy bone. Additionally, unfavorable biomechanics can also increase the risk of a mandibular fracture. Although the exact mechanism by which such fractures occur is not known, the most likely cause is the concentration of stress at the implant site. Before osseointegration occurs, the implant site acts as a region of tensile stress concentration and ultimately an area of weakness. Consequently, this area of weakness is more prone than others to applied functional forces. Repeated submaximal functional forces may lead to a spontaneous fracture with no associated macrotrauma. With these factors in mind, several extra precautions should be taken when implants are placed in thin or weak mandibles.

Before the use of implant restorations become routine, various surgical techniques were used to augment the severely atrophic mandible, prevent fractures, and facilitate prosthetic usage. These procedures included onlay grafts, sandwich osteotomy, visor osteotomy, and grafts to the border of the lower mandible. Although most of these techniques are no longer used, some can increase the stability and longevity of implants placed in atrophic mandibles. Newer strategies include short implants, autogenous bone grafts or implants, and distraction osteogenesis for augmenting mandibles 10 mm or less in height. The use of short implants is an attractive treatment option because it requires a simple surgical procedure with limited morbidity. The disadvantages of placing short implants in an atrophic mandible include long vertical lever arms and, often, the need for a tissue-borne prosthesis. Both of these mechanical issues are problematic for the patient with an atrophic mandible in which the inferior alveolar nerve is often very superficial.

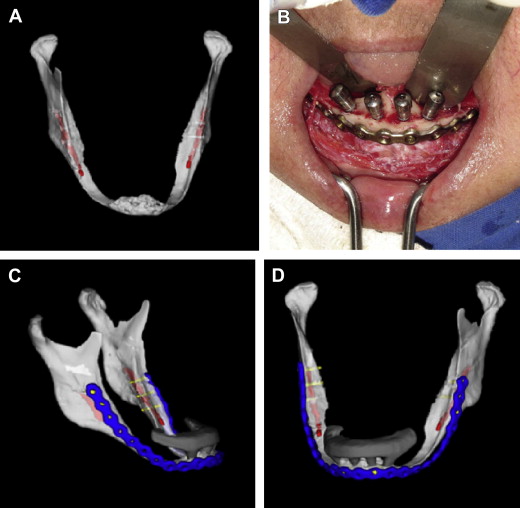

Treatment

Several published reports describe fracture of the mandible after placement of implants. The incidence of fracture is approximately 0.2%, but when it occurs it can lead to osteomyelitis, paresthesia, malunion, nonunion, and prolonged functional and nutritional disturbances. Our experience is that fractures most frequently occur on 1 side or the other of the most distal implant. When a fracture is well aligned, an effective treatment is to discontinue the use dentures and keep the patient on a soft diet. Although this treatment may be successful, our experience is that these fractures frequently require open reduction with the application of a large bone plate placed through an extraoral approach ( Fig. 4 ). When a fracture occurs between implants, an alternative treatment is to use a wire-reinforced acrylic splint over the implants to the abutments on either side spanning and connecting each side of the mandibular fracture (external intraoral splint).

A final option is an intraoral open reduction and internal fixation using a locking reconstruction plate. Although this type of reconstruction is more challenging to place, it is associated with a lower risk of injury to the marginal mandibular branch of the facial nerve, and it also avoids a facial scar. We believe that larger plates with low profiles are necessary with both the extraoral and intraoral approaches because of diminished bone stock and the loss of internal buttressing.

Prevention

A number of alternative techniques can be used to prevent a fracture in patients with atrophic mandibles. In 2009 and again in 2012, Lopes and co-workers described novel approaches to the prevention of fracture of the mandible with a 2-mm locking reconstruction bone plate. The plate was placed to reinforce the atrophic mandible before the placement of implants ( Fig. 5 ). Korpi and associates described the use of a reconstruction plate combined with the “tent pole technique” (implants stabilized in the basilar bone, leaving exposed threads above the bone covered with autogenous bone graft). These authors achieved good results by treating patients with atrophic mandible fractures with either simultaneous or delayed implant placement.

Displacement or Infringement on Adjacent Spaces

Numerous cases of displacement or migration of implants into adjacent spaces have been published, generally as case reports.

Maxilla

Displacement of an implant can occur intraoperatively or shortly thereafter because of surgical technique or anatomic variances. In contrast, migration involves the relatively long-term movement of an implant. In either case, the quantity and quality of bone is usually poor. Mechanisms that have been proposed to explain implant migration into the sinus include changes in sinus and nasal pressure, autoimmune reactions to the implant, and poor distribution of occlusal forces. Intraoperative and early displacement of dental implants has been attributed to low bone density, thin cortical bone, anatomic variances, previous infection, osteopenia or osteoporosis, and poor surgical technique. Displacement and migration of dental implants have been reported to occur in the maxillary sinus, sphenoid sinus, and ethmoid sinus. They have also been reported to perforate the nasal floor and, in 1 case, the anterior cranial fossa. In general, these types of complications result from planning errors or surgical inexperience.

When implants migrate into the sinuses, there may or may not be signs or symptoms of infection, but there will likely be an oral–antral communication. If infection occurs, it may involve the adjacent sinuses. We recommend the removal of displaced implants ( Fig. 6 ). Implants that are displaced into the maxillary sinus can be removed by a Caudwell-Luc procedure ( Fig. 7 ) or by a transnasal approach with functional endoscopic sinus surgery. An intraoral approach (Caldwell-Luc) can also be used to close an oral–antral communications. The disadvantage of a Caldwell-Luc procedure is that it gives the infection adequate access to an obstructed maxillary sinus ostium and may result in concomitant sinusitis of other paranasal sinuses. A multicenter clinical report compared 3 methods of managing implants displaced into the maxillary sinus. They concluded that functional endoscopic sinus surgery in combination with an intraoral approach can be used to safely treat complications associated with the displacement or migration of grafting materials or oral implants into the paranasal sinuses. An alternative approach is the use of intraoral videolaparoscopic trocars for removing implants form the maxillary sinus. This technique is called the double barrier approach because it uses 2 trocars. One trocar is rotated parallel to the sagittal plane to penetrate the anterior wall of the maxillary sinus. This trocar is removed from the sheath, and diagnostic endoscopy of the sinus is performed using a 45° endoscope. A second trocar is inserted through the anterior wall in close proximity to the first. Under visual control, a biopsy forceps is introduced through the second sheath. The implant is grasped under endoscopic control and extracted by removing the forceps and the cannula of the trocar.