Even if a clinician possesses basic knowledge in esthetic dentistry and clinical skills, many cases presenting in modern dental practices simply cannot be restored to both the clinician’s and the patient’s expectations without incorporating the perspectives and assistance of several dental disciplines. Besides listening carefully to chief complaints, clinicians must also be able to evaluate the patient’s physical, biologic, and esthetic needs. This article demonstrates the use of a smile evaluation form designed at New York University that assists in developing esthetic treatment plans that might incorporate any and all dental specialties in a simple and organized fashion.

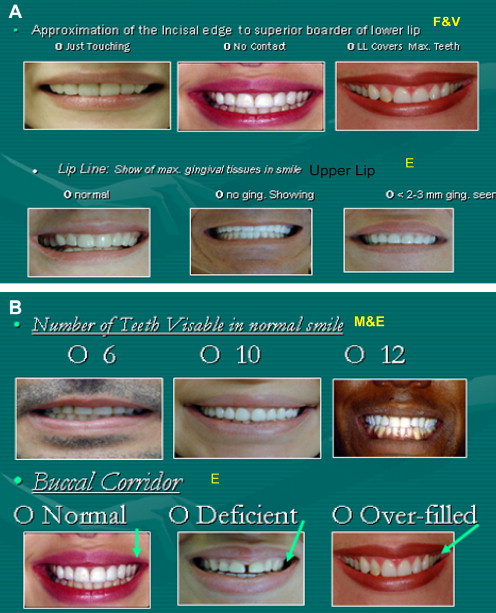

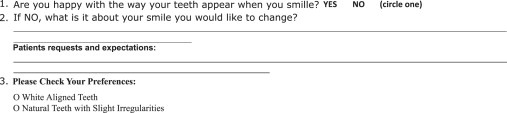

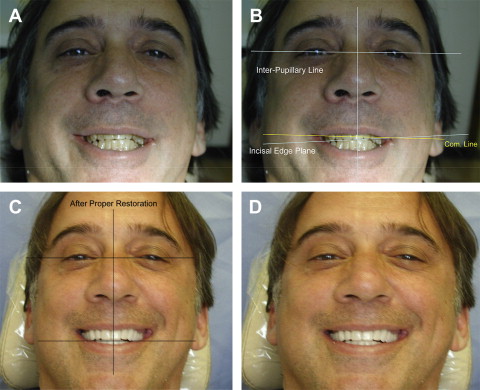

In the modern practice of dentistry, it is no longer acceptable to just repair individual teeth. Increasingly more patients are demanding a final appearance that is not only physiologically and mechanically sound but also esthetically pleasing. In addition to restoring and reconstructing the broken down dentition, bleaching, bonding, and veneering have opened the doors to a wide variety of elective dental treatments to enhance appearance, often reversing the visual signs of aging. Understanding patient expectations is critical for clinicians to develop a treatment plan that is not only sound for the dental tissue but also esthetically pleasing. Often patients may not be able to identify their needs in anything more than short sentences stating their chief complaints. Clinicians must then decide whether the expectations can be met. If these expectations cannot be met, the case will likely fail. Three simple questions, asked at the beginning of the Smile Evaluation Form, usually allow patients to express their needs clearly ( Fig. 1 ).

If clinicians believe they have the experience and ability to meet the expectations, they must then carefully consider the patient in entirety. This thorough evaluation must include a facial analysis, dental–facial analysis, and dental analysis, because each of these components and how they build on one another will provide the lattice structure for the finished case.

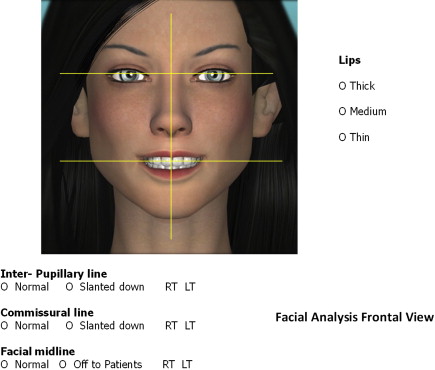

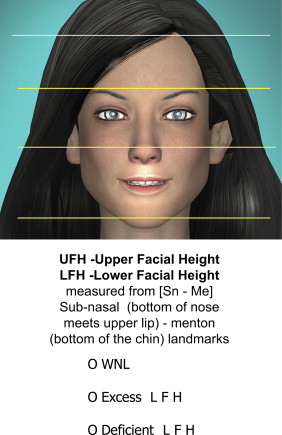

Facial analysis

Frontal View

Facial analysis is checked at a conversational distance. The clinician uses a series of horizontal and vertical lines to determine the size and proportion of the face from chin to hairline and also the relationship of the patient’s face and dentition in space ( Figs. 2–4 ).

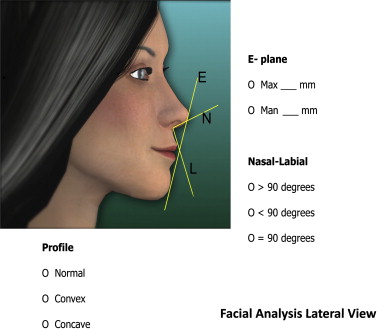

A profile view ( Fig. 5 ) allows clinicians to visualize an important imaginary line called the Rickett’s E-plane . This line drawn from the tip of the nose to the tip of the chin allows the profile of the patient to be evaluated by comparing the distance from this plane to the top and bottom lip. In the normal profile, the maxillary lip is approximately two times the distance (4 mm) as the lower lip to the E-plane. A concave profile may call for a more prominent position of the maxillary anterior teeth with final restoration of the anterior teeth, whereas a more convex profile may require a more retruded position of the final restorations. Other imaginary lines form the nasal/labial line angle. In men the nasal-labial angle is generally 90° to 95°, whereas in women it is generally 100° to 105°.

Incisal and Occlusal Analysis

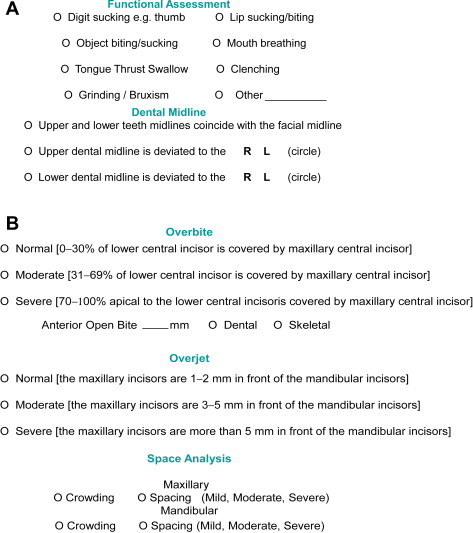

Next on the Smile Evaluation Form, the incisal and occlusal analysis is evaluated. This evaluation involves a good history that allows the clinician to diagnose whether habits have affected the occlusion, angulations, and buccal-lingual positioning of the teeth. If the clinician does not know the cause of an existing malocclusion/malposition, rebuilding the dentition may have short-lived outcomes. Overbite, overjet, space analysis, and classifications of occlusion and malocclusion should be evaluated carefully.

The functional assessment ( Fig. 6 A) occurs when a dental history is taken, and includes observations of the patient’s swallowing and breathing during the initial visit. A thorough intraoral examination may show signs of bruxism and wear that could indicate incisal and occlusal disharmony. This evaluation also provides the best opportunity for clinicians to determine whether the facial and dental midlines are coincidental. If the maxillary or mandibular midlines deviate from the facial midline, this should be noted. Canting (a dental midline that is not parallel to the facial midline) has been shown to be even more discernable to patients and is considered more of a handicap than dental midlines that are not coincidental but are at least parallel. A space analysis should also be categorized and noted.

In Fig. 6 B, a generalized orthodontic evaluation (classification of occlusion or malocclusion) is noted. Orthodontic intervention may be considered a possible treatment adjunct or choice at this time.

Phonetic Analysis

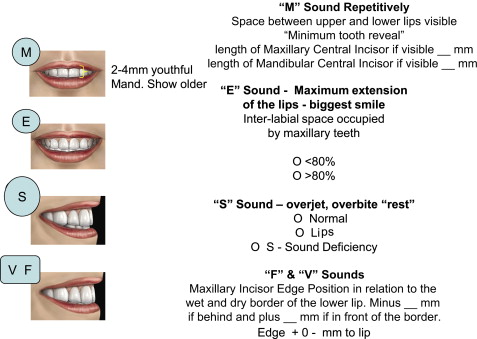

In the 1950s, clinicians realized the importance of phonetics in determining denture teeth setup and appropriate anterior tooth position and length in relation to vertical dimension of occlusion. A patient in physiologic rest position will normally have a 2- to 4-mm space between the upper and lower arch. The minimum facial reveal of anterior teeth in this position for a youthful appearance has been identified as between 2 and 4 mm, depending on the sex of the individual (women generally show more tooth).

The “m” sound allows a view of the rest position and the tooth reveal at this position. One may use this a phonetic guide to help plan the look to be achieved in the initial wax up of a well-planned case ( Fig. 7 ).

The extended pronunciation of the “e” sound is another important phonetic guide. This sound will usually show the widest smile. Thus, the practice of saying the word “cheese” when taking photos. The space between the upper and lower lips should be filled almost completely by the maxillary incisors in pronouncing this sound. The Maxillary incisal edge will be very close to the superior border of the lower lip. However, as aging occurs, the muscles of the mouth lose tone, and increasingly less of the maxillary teeth will be visible during the pronunciation of the long “e” sound.

The “s” sound is created by air passing between the soft surface of the tongue and the hard lingual surface of the maxillary anterior teeth.

Correct pronunciation of the “f” and “v” sounds is accomplished when the incisal edges of the maxillary anterior teeth come in light contact with the lower lip (vermilion border). The incisal edges should be stationed directly over the line of demarcation between the wet and dry boarder of the lower lip. This mild contact allows a buildup of sufficient pressure for correct pronunciation.

Dental Analysis

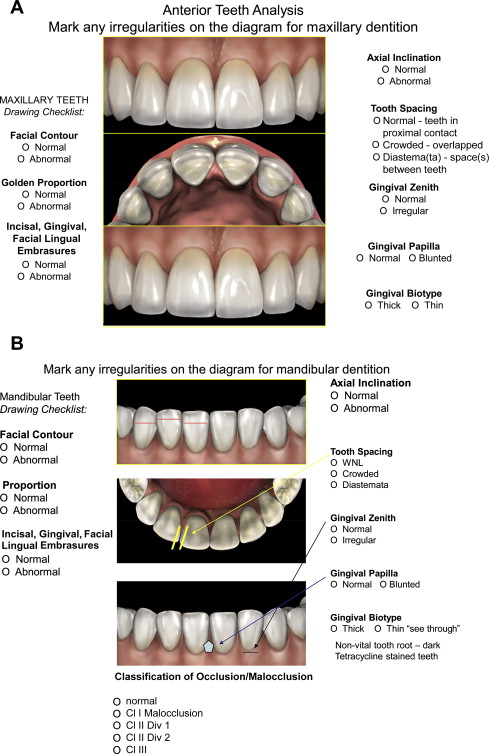

The maxillary and mandibular anterior dental analysis is made directly on the form using direct diagramming on the simple drawings or using the drawing checklist ( Fig. 8 ). Facial contours that are irregular may be best seen in the incisal views, whereas golden proportion, incisal embrasures, axial inclination, tooth spacing, and gingival zeniths can be drawn directly on the facial views. Gingival biotype is also important to note, especially when deciding on the type of restoration to be used, because a thin biotype might require further gingival preparation to cover dark roots.

Dentofacial Analysis

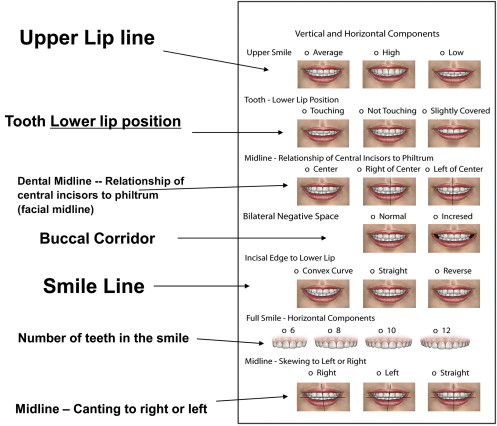

A thorough dentofacial analysis is a critical component in determining the fine details of designing the restorations that will deliver the final esthetics of the case. Identifying the patient’s horizontal and vertical components as either normal or needing improvement will help determine how the case should proceed ( Fig. 9 ). After the Smile Evaluation Form has been used numerous times, the dentofacial analysis allows quick and accurate identification of problems. Any component that may require consultation with another discipline is easily identified and recorded.

Understanding the language of esthetics, a topic covered by Davis in 2007, will help readers understand the diagrams on the Smile Evaluation Form. This article explains the significance of important definitions such as lip line, midline, teeth exposed in physiologic rest position, and bilateral negative space. Fig. 10 shows examples of normal and abnormal smiles. Most variations are present on the form to easily compare with the patient. In summary, the Smile Evaluation Form provides practitioners with a simple method of quickly notating the esthetic needs of the patient, and thereby will identify the disciplines that may need to be involved in a thorough treatment plan. This organized checklist provides clinicians with a goal, thereby allowing treatment sequencing to be planned better. The case presented in the next section was planned using this form and shows its usefulness ( Figs. 11–26 ).