Treatment of maxillofacial trauma has evolved in the past 50 years as a result of technologic advances in diagnostic capabilities, improved rigid fixation techniques, and more specialized approaches to surgical training. Nonetheless, even in the hands of the most experienced surgeons, there is still the potential for the development of secondary morbidity, such as malunion, malocclusion, and temporomandibular joint (TMJ) dysfunction. Therefore, management of patients with facial trauma requires that the clinician not only address the acute injuries but also be prepared to address any secondary morbidities should they arise. An understanding of the causes and management of post-traumatic deformities will allow the surgeon to reduce the likelihood of the development of these deformities.

The primary objective of this chapter is to address the initial assessment, treatment planning, and subsequent surgical correction of post-traumatic maxillomandibular skeletal deformities, particularly secondary (late) reconstruction of maxillofacial skeletal trauma.

Etiopathogenesis/Causative Factors

Few reconstructive procedures are more challenging than the surgical repair of facial deformities secondary to trauma, and patients who suffer severe facial trauma may never function or appear as they did before the traumatic incident. This is in contrast to what is observed with congenital deformities, where any surgical intervention will result in major improvement and patient satisfaction. Nonetheless, although a plethora of literature exists on the epidemiology of facial trauma, unfortunately, very little is known about the epidemiology of post-traumatic maxillomandibular deformities caused by a myriad of local and systemic variables that contribute to these deformities. Even though the incidence of post-traumatic maxillomandibular deformities is unknown, they are assumed to be relatively uncommon. Therefore, the best method for the prevention of most secondary post-traumatic maxillomandibular deformities is to perform appropriate treatment as soon as possible after injury.

As stated previously, the most common causes of post-traumatic maxillomandibular deformities include malunion, malposition, and nonunion of fractures because of an inadequate postoperative interocclusal relationship or bony reduction and fixation. In addition, secondary repair may be required in critically injured patients too unstable to undergo general anesthesia for primary repair of their facial injuries (neurologic instability, for example). Manson attributes malunion to poor visualization, telescoping of bone fragments, and in patients with mandibular fractures, rotation of the mandible in a lingual direction. Ellis’ group reviewed 33 cases of delayed treatment of pan-facial fractures in which most patients required delayed treatment because of severe brain injury (60% of patients); the others had associated injuries such as limb fractures. Interestingly, all 33 patients had malocclusion and facial deformities, 20 (60%) had mouth opening limited to less than 30 mm, and 5 (15%) had ankylosis of the TMJ. The challenge in treating delayed cases is that it is believed that after a 3-week period, bone healing enters what is termed the “gray stage,” during which the edges of bone fragments are undergoing resorption and remodeling, which can make achieving ideal bone reduction very difficult and can lead to malunion, nonunion, or even a bone defect.

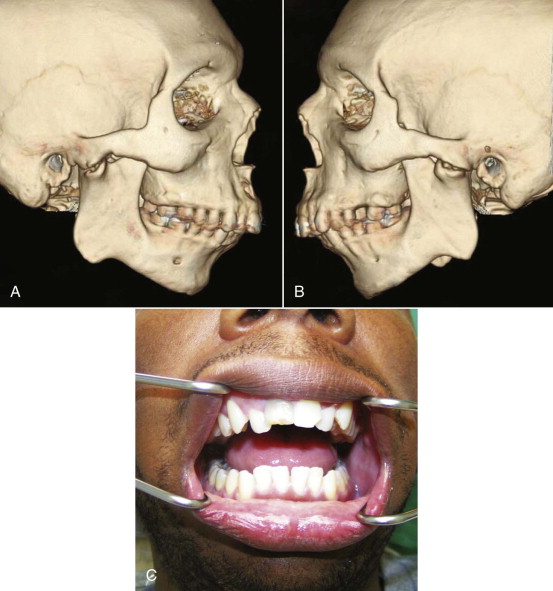

Other common causes of post-traumatic maxillomandibular malunion include the ever-controversial condylar fracture. This is a fracture whose management should be considered seriously, especially in the pediatric population and adults with a condylar head fracture, since the most commonly encountered hard tissue complication after sustaining facial trauma is TMJ dysfunction. One such example is a bilateral condylar fracture, which when inadequately diagnosed or treated, can result in an open bite, trismus, or hypoplasia of the mandible, especially if it occurs in a pediatric patient ( Fig. 46-1 ).

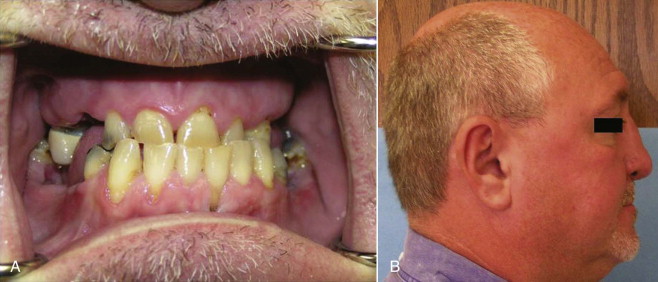

With regard to mid-face trauma, the most common cause of postoperative malocclusion after the treatment of mid-face trauma is maxillary widening or impaction when the transverse or anteroposterior dimensions (or both) were altered intraoperatively ( Fig. 46-2 ). In a patient with an impacted maxilla, the most common complaint is impaction of the nose. Additionally, in the management of comminuted mid-face fractures, an oblique or tilted occlusal plane can easily develop.

Pathologic Anatomy

Most post-traumatic facial deformities tend to involve either the maxilla or the mandible. Additionally, the mandible has been classically described as the esthetic and functional foundation of the lower part of the face. The ultimate goals of secondary reconstruction of the anatomic regions of the mandible are aimed at reconstituting its three-dimensional shape while achieving excellent orofacial rehabilitation.

The goals of post-traumatic maxillary reconstruction are nearly the same as those for post-traumatic mandibular reconstruction but with additional anatomic structures such as the maxillary sinus and the horizontal and vertical facial buttresses. The maxilla is made up of six walls, with the superior, anterior, and inferior walls being the most significant in maxillary reconstruction. The inferior wall makes up the alveolus and is required for prosthodontic rehabilitation, the superior wall is part of the orbit and is required for orbital support, and the anterior wall determines cheek projection and makes a significant contribution to facial dimension in the sagittal plane. Facial disfigurement can result from lack of mid-face bony support because of a deficiency in maxillary buttress vertical support or a maxillary sagittal plane deficiency.

Pathologic Anatomy

Most post-traumatic facial deformities tend to involve either the maxilla or the mandible. Additionally, the mandible has been classically described as the esthetic and functional foundation of the lower part of the face. The ultimate goals of secondary reconstruction of the anatomic regions of the mandible are aimed at reconstituting its three-dimensional shape while achieving excellent orofacial rehabilitation.

The goals of post-traumatic maxillary reconstruction are nearly the same as those for post-traumatic mandibular reconstruction but with additional anatomic structures such as the maxillary sinus and the horizontal and vertical facial buttresses. The maxilla is made up of six walls, with the superior, anterior, and inferior walls being the most significant in maxillary reconstruction. The inferior wall makes up the alveolus and is required for prosthodontic rehabilitation, the superior wall is part of the orbit and is required for orbital support, and the anterior wall determines cheek projection and makes a significant contribution to facial dimension in the sagittal plane. Facial disfigurement can result from lack of mid-face bony support because of a deficiency in maxillary buttress vertical support or a maxillary sagittal plane deficiency.

Diagnostic Studies

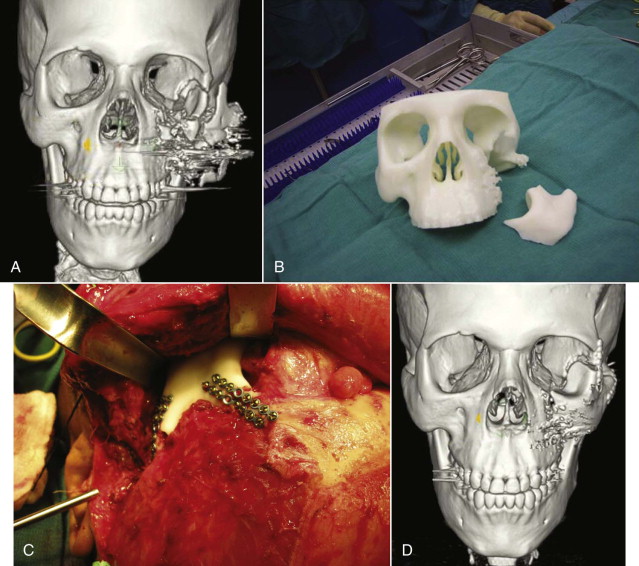

A thorough history and physical examination are critical for proper assessment of patients with post-traumatic deformities. The following data should be ascertained first: date of injury, mechanism of injury, and any associated injuries. The surgeon must rule out any associated intracranial, cervical spine, abdominal, or thoracic injuries, as well as any injury that would contraindicate the use of maxillomandibular fixation (MMF). Additionally, an assessment of trigeminal neurosensory function and visual function should always be carried out and documented because of the risk for compromise of these structures during traumatic incidents affecting the maxillofacial region. More focused diagnostics should consist of an analysis of facial esthetics, as well as more quantitative measurements (i.e., cephalometric image analysis). Similarly, mounted dental anatomic casts and study models are also another important component of a proper work-up of these patients. In addition, three-dimensional computed tomography (CT) and at times stereolithographic skull models can be quite useful in patients with more severe deformity, especially in providing an appreciation of the displaced skeletal structures ( Fig. 46-3 ). Both have been shown to be useful in minimizing surgical approaches, saving operating time, providing a better understanding of the planes of the deformity, and even improving postoperative results in major facial reconstructive cases. Three-dimensional CT and stereolithographic models can also be useful in planning surgery in patients with severe trauma when radiographic examination and cast analysis are impossible to obtain. Plain films are indicated only for cephalometric evaluation; aside from this, they provide minimal significant information.

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses