Salivary gland abnormalities and salivary dysfunction are important orofacial disorders. Patients with such problems are usually seen in the dental office for evaluation and therapy, and the dental practitioner is required to make a diagnosis and institute care. Therefore, it is necessary for the dentist to be knowledgeable regarding the more common pathologic entities that involve the salivary apparatus, and also be familiar with the diagnostic and therapeutic tools that are available. Successful diagnosis is dependent on the organized integration of the information derived from past history, clinical examination, salivary volume study, imaging, serology, and histopathologic examination. This article discusses the most common disorders seen in the Salivary Gland Center and indicates the current approaches to diagnosis. Improvement in diagnostic skills will avoid serious complications and lead to specific and effective therapy.

Salivary gland disease

Salivary gland abnormalities and salivary dysfunction are important orofacial disorders. Because of their anatomic location and subjective oral complaints, patients with such problems are usually seen in the dental office for evaluation and therapy. Inevitably, the dental practitioner will be required to make a diagnosis and institute care. Therefore, it is necessary for the dentist to be knowledgeable regarding the more common pathologic entities that involve the salivary apparatus, and also be familiar with the diagnostic and therapeutic tools that are available.

Since its establishment, the Salivary Gland Center (SGC) at Columbia University College of Dental Medicine has had the opportunity to examine more than 8000 patients with salivary gland disorders, ranging in age from infancy to the aged. Successful diagnosis has proved to be dependent on the organized integration of the information derived from the available diagnostic modalities: past history, clinical examination, salivary volume study, imaging, serology, and histopathologic examination. With the attainment of a complete work-up, an accurate diagnosis can be made and a meaningful therapeutic approach can be achieved.

Numerous salivary gland and/or secretory dysfunctions exist. This article highlights and defines the most common disorders seen in the SGC and indicates the current approaches to diagnosis. Improvement in diagnostic skills will avoid serious complications and lead to specific and effective therapy.

False-positives

False-positive patients represent the largest group of individuals seen in the SGC. These patients feature a variety of subjective complaints and/or objective conditions mimicking a salivary problem. Because of their multiplicity, only the more commonly seen entities are discussed in this article.

Somatoform Disease

The SGC has observed that, despite their complaints, many of its patients do not have problems associated with their salivary glands and/or saliva. Instead, these patients have somatoform disease (SD), which can be defined as a psychological disorder manifesting as a subjective complaint with no organic basis. These patients have many bizarre and objectively nonsubstantiated concerns related to their saliva. Thick saliva, granular or gritty saliva, foamy saliva (a normal condition that results when accumulated saliva is aerated by tongue movement), slimy saliva, a need to constantly expectorate or swallow, and with the problem often limited to a specific area of the mouth, all frequently represent the impetus for consultation. Patients often state that they have too little or too much saliva, but this is not borne out by volume studies.

The history of these patients is a significant aspect in diagnosis. They frequently have histories of anxiety or depression and are being treated with psychotherapeutic drugs. Other common denominators include a burning mouth and altered taste sensation, often reported as metallic in nature. The psychotherapeutics, along with many other medications, are anticholinergic and cause hyposalivation when the glands are at rest. However, salivary stimulation produces normal volumes because stimulation overcomes the effect of the drug. Conversely, salivary volume in salivary gland disease is diminished in both at rest and in stimulated volume studies. This difference is the key to differentiating true hyposalivation from perceived hyposalivation. In determining salivary volume, the SGC uses the established criteria for measuring stimulated flow rates with a Carlsen-Crittenden collector (normal 0.4–1 mL/min per parotid gland). The clinician should also be aware that some medications, as well as some systemic diseases, can alter taste.

There are other common factors shared by the patient with SD. Questioning may indicate that some oral event or dental procedure was the precipitating factor for the problem. Concurrently, many patients exhibit other abnormal oral conditions, such as bruxing/clenching or unusual facial pain patterns, that may have a psychogenic origin. Stressful work environments or problematic social relationships can be contributing factors.

With no demonstrable organic basis for the complaint, treatment requires reassurance and/or psychiatric consultation. Patients often resist this suggestion for help.

Masseteric Hypertrophy

Masseteric hypertrophy can be caused by constant bruxing, clenching, or continuous gum chewing. With enlargement of the masseteric muscle, the face develops a rectangular configuration ( Fig. 1 ). Confusion occurs when these patients are misdiagnosed with parotid hypertrophy (PH). Clinical differentiation is possible because accentuation of facial ovality occurs with PH. In addition, when the palm of the hand is placed on the facial swelling and the patient clenches, the previously enlarged muscle becomes even larger and displaces the hand laterally. The condition is usually seen in young individuals. Elderly patients with dental deterioration develop discomfort when activated masseters stress their dentition. Radiographically, bony hyperplasia, scalloping, and the development of an exostosis may be noted in the mandibular gonial angle region, and result from the stimulatory effect on bone from increased masseter tension at its insertion ( Fig. 2 ).

For cosmetic reasons, botulinum toxin injections have been used to inactivate the muscle and cause muscle atrophy. Muscle relaxants, behavioral modification, occlusal guards, and surgical muscle reduction are additional options for decreasing the masseter’s bulk.

Lymphadenopathy

An understanding of the anatomic location of cervicofacial lymph nodes, plus a knowledge of the pathologic entities that cause lymphadenopathy, differentiate lymphadenopathy from sialadenopathy. Bacterial lymphadenitis, originating from a tooth or mucosal infection, is the most common cause of an enlarged lymph node in the SGC. Granulomatous and autoimmune diseases, metastatic malignancies, and lymphomas can also cause salivary gland area lymphadenopathies and complicate the diagnostic process.

The history, physical examination, and clinical findings, along with knowledge of lymphatic anatomy and drainage patterns, are mandatory for diagnosis. The sudden onset of a painful, circumscribed, movable nodule suggests a lymphadenitis. Neoplastic nodes tend to be persistent, painless, movable, but can be fixed when malignant, and enlarge over time. A simple method to differentiate a lymphadenitis from a sialadenitis is to observe expressed saliva from the suspected salivary gland. A cloudy saliva suggests the presence of pus from an infected gland (sialadenitis), whereas clear saliva implies an extraglandular process.

Imaging (computed tomography [CT] scan or magnetic resonance imaging [MRI]) is helpful to identify the presence of a lymphadenopathy. Biopsy, whether by fine-needle aspiration or tissue biopsy, affords the opportunity for definitive histopathologic study and diagnosis, and guides the therapeutic choice.

Neuromuscular Dysfunction

Drooling patients have an inability to manage their normal salivary volume, whereas patients with hypersalivation produce a true excessive salivary volume. The drooling problem originates from the neuromuscular dysfunction seen in patients with Parkinson disease, amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, demyelinating diseases, poliomyelitis, or a muscular dystrophy. Patients who have received cervical radiation or who are developmentally disabled also drool. Saliva accumulating in the anterior floor of the mouth, combined with a tendency for the head to lean forward, result in the propensity of these patients to drool. Salivary volume studies testify that excessive saliva is not produced.

Relief can be attained with the use of antisialogogic medications (atropine, scopalamine, antihistamines), low-dosage radiation, botulinum toxin injections, salivary duct repositioning, and even surgical interruption of the nerve supply to the salivary glands.

Dental Conditions

Saliva has a protective effect in preventing dental disease. Patients with extensive dental caries are often referred to the SGC. An assumed deficiency in salivary volume or quality is the impetus for the referral. Patients with decreased saliva and caries related to Sjögren syndrome (SS) or who have received head/neck radiation are readily recognized. However, hyposalivation induced by medications does not seem to be severe enough to cause rampant caries. Patients with reflux disease regurgitate gastric acids and develop dental erosions.

Once caries initiated by SS or radiation have been ruled out, suspicion should be directed toward an exogenous cause such as diet. Patients with an extremely high sucrose intake originating from soft drinks, sugared juices, candy, mints, or bubble gum have all been referred to the SGC. Despite the presence of extensive decay in these patients, salivary flow is normal. Their diagnosis is dependent on a thorough dietary history, which can suggest the cause of the rampant caries.

Treatment requires diet modification, good oral hygiene, fluoride therapy, and dental rehabilitation.

Paraglandular Opacities

Calcifications, when they occur in the region of a salivary gland, can be falsely interpreted as salivary stones. Differentiation is based on the absence of the pain and swelling associated with obstructive sialadenitis. Problems in diagnosis occur because asymptomatic stones exist.

Many lymph nodes are anatomically situated in close proximity to the salivary glands. Healing of such an inflamed node can result in calcification that mimics a salivary stone. Other causes of lymph node calcification include parasitic diseases, tuberculosis, sarcoid, metabolic diseases, and lymphoma. The key to diagnosis rests in anatomic knowledge and the absence of the signs and symptoms of sialadenitis.

A panoramic film can show spherical calcifications, varied in number and size, superimposed on the mandibular ramus ( Fig. 3 ). A diagnosis of parotid stones is often made. However, the opacities are frequently tonsilloliths. The CT scan’s axial view reveals these tonsilloliths to be medial to the ramus and associated with the pharyngeal space.

Other opacities noted in the area of the salivary glands must also be considered in differential diagnosis. They include aortic vessel calcifications, calcified thrombi (phleboliths) seen in cervicofacial vascular conditions, acne calcifications, and foreign bodies.

False-positives

False-positive patients represent the largest group of individuals seen in the SGC. These patients feature a variety of subjective complaints and/or objective conditions mimicking a salivary problem. Because of their multiplicity, only the more commonly seen entities are discussed in this article.

Somatoform Disease

The SGC has observed that, despite their complaints, many of its patients do not have problems associated with their salivary glands and/or saliva. Instead, these patients have somatoform disease (SD), which can be defined as a psychological disorder manifesting as a subjective complaint with no organic basis. These patients have many bizarre and objectively nonsubstantiated concerns related to their saliva. Thick saliva, granular or gritty saliva, foamy saliva (a normal condition that results when accumulated saliva is aerated by tongue movement), slimy saliva, a need to constantly expectorate or swallow, and with the problem often limited to a specific area of the mouth, all frequently represent the impetus for consultation. Patients often state that they have too little or too much saliva, but this is not borne out by volume studies.

The history of these patients is a significant aspect in diagnosis. They frequently have histories of anxiety or depression and are being treated with psychotherapeutic drugs. Other common denominators include a burning mouth and altered taste sensation, often reported as metallic in nature. The psychotherapeutics, along with many other medications, are anticholinergic and cause hyposalivation when the glands are at rest. However, salivary stimulation produces normal volumes because stimulation overcomes the effect of the drug. Conversely, salivary volume in salivary gland disease is diminished in both at rest and in stimulated volume studies. This difference is the key to differentiating true hyposalivation from perceived hyposalivation. In determining salivary volume, the SGC uses the established criteria for measuring stimulated flow rates with a Carlsen-Crittenden collector (normal 0.4–1 mL/min per parotid gland). The clinician should also be aware that some medications, as well as some systemic diseases, can alter taste.

There are other common factors shared by the patient with SD. Questioning may indicate that some oral event or dental procedure was the precipitating factor for the problem. Concurrently, many patients exhibit other abnormal oral conditions, such as bruxing/clenching or unusual facial pain patterns, that may have a psychogenic origin. Stressful work environments or problematic social relationships can be contributing factors.

With no demonstrable organic basis for the complaint, treatment requires reassurance and/or psychiatric consultation. Patients often resist this suggestion for help.

Masseteric Hypertrophy

Masseteric hypertrophy can be caused by constant bruxing, clenching, or continuous gum chewing. With enlargement of the masseteric muscle, the face develops a rectangular configuration ( Fig. 1 ). Confusion occurs when these patients are misdiagnosed with parotid hypertrophy (PH). Clinical differentiation is possible because accentuation of facial ovality occurs with PH. In addition, when the palm of the hand is placed on the facial swelling and the patient clenches, the previously enlarged muscle becomes even larger and displaces the hand laterally. The condition is usually seen in young individuals. Elderly patients with dental deterioration develop discomfort when activated masseters stress their dentition. Radiographically, bony hyperplasia, scalloping, and the development of an exostosis may be noted in the mandibular gonial angle region, and result from the stimulatory effect on bone from increased masseter tension at its insertion ( Fig. 2 ).

For cosmetic reasons, botulinum toxin injections have been used to inactivate the muscle and cause muscle atrophy. Muscle relaxants, behavioral modification, occlusal guards, and surgical muscle reduction are additional options for decreasing the masseter’s bulk.

Lymphadenopathy

An understanding of the anatomic location of cervicofacial lymph nodes, plus a knowledge of the pathologic entities that cause lymphadenopathy, differentiate lymphadenopathy from sialadenopathy. Bacterial lymphadenitis, originating from a tooth or mucosal infection, is the most common cause of an enlarged lymph node in the SGC. Granulomatous and autoimmune diseases, metastatic malignancies, and lymphomas can also cause salivary gland area lymphadenopathies and complicate the diagnostic process.

The history, physical examination, and clinical findings, along with knowledge of lymphatic anatomy and drainage patterns, are mandatory for diagnosis. The sudden onset of a painful, circumscribed, movable nodule suggests a lymphadenitis. Neoplastic nodes tend to be persistent, painless, movable, but can be fixed when malignant, and enlarge over time. A simple method to differentiate a lymphadenitis from a sialadenitis is to observe expressed saliva from the suspected salivary gland. A cloudy saliva suggests the presence of pus from an infected gland (sialadenitis), whereas clear saliva implies an extraglandular process.

Imaging (computed tomography [CT] scan or magnetic resonance imaging [MRI]) is helpful to identify the presence of a lymphadenopathy. Biopsy, whether by fine-needle aspiration or tissue biopsy, affords the opportunity for definitive histopathologic study and diagnosis, and guides the therapeutic choice.

Neuromuscular Dysfunction

Drooling patients have an inability to manage their normal salivary volume, whereas patients with hypersalivation produce a true excessive salivary volume. The drooling problem originates from the neuromuscular dysfunction seen in patients with Parkinson disease, amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, demyelinating diseases, poliomyelitis, or a muscular dystrophy. Patients who have received cervical radiation or who are developmentally disabled also drool. Saliva accumulating in the anterior floor of the mouth, combined with a tendency for the head to lean forward, result in the propensity of these patients to drool. Salivary volume studies testify that excessive saliva is not produced.

Relief can be attained with the use of antisialogogic medications (atropine, scopalamine, antihistamines), low-dosage radiation, botulinum toxin injections, salivary duct repositioning, and even surgical interruption of the nerve supply to the salivary glands.

Dental Conditions

Saliva has a protective effect in preventing dental disease. Patients with extensive dental caries are often referred to the SGC. An assumed deficiency in salivary volume or quality is the impetus for the referral. Patients with decreased saliva and caries related to Sjögren syndrome (SS) or who have received head/neck radiation are readily recognized. However, hyposalivation induced by medications does not seem to be severe enough to cause rampant caries. Patients with reflux disease regurgitate gastric acids and develop dental erosions.

Once caries initiated by SS or radiation have been ruled out, suspicion should be directed toward an exogenous cause such as diet. Patients with an extremely high sucrose intake originating from soft drinks, sugared juices, candy, mints, or bubble gum have all been referred to the SGC. Despite the presence of extensive decay in these patients, salivary flow is normal. Their diagnosis is dependent on a thorough dietary history, which can suggest the cause of the rampant caries.

Treatment requires diet modification, good oral hygiene, fluoride therapy, and dental rehabilitation.

Paraglandular Opacities

Calcifications, when they occur in the region of a salivary gland, can be falsely interpreted as salivary stones. Differentiation is based on the absence of the pain and swelling associated with obstructive sialadenitis. Problems in diagnosis occur because asymptomatic stones exist.

Many lymph nodes are anatomically situated in close proximity to the salivary glands. Healing of such an inflamed node can result in calcification that mimics a salivary stone. Other causes of lymph node calcification include parasitic diseases, tuberculosis, sarcoid, metabolic diseases, and lymphoma. The key to diagnosis rests in anatomic knowledge and the absence of the signs and symptoms of sialadenitis.

A panoramic film can show spherical calcifications, varied in number and size, superimposed on the mandibular ramus ( Fig. 3 ). A diagnosis of parotid stones is often made. However, the opacities are frequently tonsilloliths. The CT scan’s axial view reveals these tonsilloliths to be medial to the ramus and associated with the pharyngeal space.

Other opacities noted in the area of the salivary glands must also be considered in differential diagnosis. They include aortic vessel calcifications, calcified thrombi (phleboliths) seen in cervicofacial vascular conditions, acne calcifications, and foreign bodies.

Gastroesophageal reflux disease

Interference with the function of the lower esophageal sphincter (LES), which normally guards against retrograde movement of gastric acids, is a major factor in the development of gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD). In pregnancy, an increase in circulating hormones seems to decrease LES contractility, whereas anatomic changes associated with a hiatal hernia may physically impair LES function and/or clearance of acid from the esophagus.

With gastric acid intrusion into the esophagus, esophageal irritation follows and the subjective symptoms of heartburn develop (midline retrosternal burning sensations). Esophageal peristalsis may not be sufficient to rapidly clear the gastric acid and prevent esophageal damage. Limitation of the acid’s effect seems to occur when the esophageal salivary reflex (ESR), mediated through vagal afferents, comes into play. Stimulation of the ESR causes episodic hypersalivation (water brash). With the inevitable swallow, the salivary hypersecretion lavages the esophageal wall and the buffering system neutralizes any residual gastric acid. Significant esophageal wall damage (Barrett esophagitis) from chronic exposure to the contents of gastric acid reflux is discouraged when the increased salivary flow flushes the esophageal wall and buffers the acid.

Many patients simultaneously develop episodic hypersalivation and heartburn. The precipitating factor (hypersalivation) for their visit to the SGC occurs when heartburn activates the ESR. A complaint of nocturnal drooling, causing maceration in the lip commissure area, can develop ( Fig. 4 ). The supine sleeping position favors retrograde movement of stomach contents into the esophagus and saliva is stimulated. The regurgitation of gastric acids may extend beyond the esophagus and cause vocal cord damage and dental erosions. During an episode of heartburn, salivary volume measurements substantiate the existence of increased salivation and serve as a diagnostic tool.

Water brash can be ameliorated by treating the GERD, thus inhibiting ESR excitation. Prescribed medications for GERD include metoclopramide, cimetidine, and other antacids. Avoidance of spicy foods, alcohol, chocolate, and large meals, and elevation of the head during sleep have proved to be helpful in treating heartburn and the associated hypersalivation.

Sialosis (sialadenosis)

Sialosis is characterized by a persistent, painless, bilateral parotid gland swelling with occasional involvement of the submandibular salivary gland. The parotid swellings are soft in tone, noninflammatory, non-neoplastic, usually symmetric, do not fluctuate in size, and often become a cosmetic issue. It occurs most commonly in alcoholism, but it can develop in diabetes, malnutrition, and even idiopathically.

Autonomic neuropathy, manifesting as a demyelinating polyneuropathy, seems to be the common causal denominator uniting these disparate systemic conditions. The sympathetic innervation to individual secreting acinar cells is disturbed. This neuropathy results in excessive acinar protein synthesis and/or inhibition of its secretion. Cellular enlargement then results from intracytoplasmic engorgement by zymogen granules and causes the clinically visible PH.

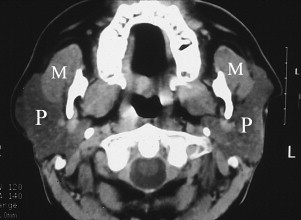

Diagnosis is best attained by integrating the medical history and signs and symptoms obtained from the physical examination with data derived from varied investigative clinical modalities. Sialographic imaging shows a normal pattern of duct distribution and normal duct calibers. However, the ducts are distributed over an extremely large area, reflecting the clinically evident glandular hypertrophy. A CT scan of the parotid glands clearly shows glandular hypertrophy as the cause of the increased facial bulk ( Fig. 5 ). In addition, the enlarged parenchymal cells replace the normally present lucent intraparotid fat and result in an increased gland density. Conversely, on occasion, a marked fatty infiltration of the parotid is seen. It is thought that, in the acute stage of sialosis, cellular hypertrophy is present, whereas the chronic stage is represented by a marked fatty infiltration.