This article discusses the classic autoimmune diseases: pemphigus vulgaris, mucosal pemphigoid, and oral lichen planus. These are generally considered of autoimmune origin or, at a minimum, immune system mediated. Cause, diagnosis, and treatment are discussed. As management of these diseases progresses, continued advances in molecular pathogenesis will allow insight into which strategies can be employed in interfering with the complex cascade of events leading to mucosal impairment and clinical morbidity.

Oral mucosal diseases are frequently encountered in daily practice, with associated degrees of concern and symptomatology on the part of the patient. Whereas most types of primary mucous membrane disease or conditions are commonplace, self-limiting, and episodic—such as recurrent aphthous stomatitis—others often may be difficult to characterize and manage, leading to longer than acceptable periods of discomfort and concern.

The autoimmune-associated diseases are a group of conditions that, although relatively uncommon, may lead to long periods of failed intervention, based on absence of a definitive diagnosis on one hand and unfamiliarity with effective therapeutics on the other. Involvement of areas beyond the oral cavity also may be a factor in overall disease management. The mouth is often the indicator or harbinger of more widespread lesions, with a corresponding opportunity to intervene early, leading to the opportunity for timely consultation with other members of the health care team, and the possible reduction of overall morbidity from these conditions.

Specific conditions discussed in this article include the classic autoimmune diseases pemphigus vulgaris (PV) (benign mucous membrane pemphigoid) and mucosal pemphigoid (MP) (cicatricial pemphigoid); as well as oral lichen planus (OLP), generally considered of autoimmune origin or, at a minimum, immune system mediated in the absence of a defined “lichen planus (LP) antigen.”

PV

PV represents one of several mucocutaneous blistering diseases where oral lesions are commonly observed. It is considered a very rare condition in which an acantholytic process characterizes the skin and oral mucosal lesions. At times the oral lesions may dominate the initial presentation, with one recent study indicating that the oral mucosa is the primary site of 75% of new cases. As is often the case for PV flaccid vesicles involving the keratinized and nonkeratinized lining, structures rapidly evolve into erosions and ulcerations with ill-defined margins and sloughing of the superficial layers of epithelium. The course of this condition is typically chronic and, before the introduction and use of systemic corticosteroids, was often fatal with death usually due to infection, sepsis, or dehydration.

A significant number of cases demonstrate a strong genetic or familial, as well as ethnic relationship, primarily within the Ashkenazi Jewish population and those of Mediterranean descent. In common clinical practice within a multicultural and multiracial setting, many groups are represented with classic PV. This is amplified when studying PV associations with HLA class II alleles (those entities largely responsible for T-lymphocyte recognition of desmogleins [Dsg] 3 peptides) and the country of origin of those studies. In a large retrospective analysis of 159 cases a female/male ratio was approximately 2:1, while the mean age was 53 years.

Cause or Pathophysiology

The pathologic process is mediated by autoantibodies that target the extracellular adhesion components, chiefly within the cadherin group of cell-cell adhesion molecules, particularly Dsg, which in the case of oral PV is mainly Dsg 3 and, to a much lesser extent, Dsg 1. Those individuals with predominantly or exclusively oral lesions only will demonstrate only antibodies to Dsg 3 in the early phases of this disease. However, if untreated, over time the phenomenon of epitope spread may occur with Dsg 1 recognized and attacked as well, producing concomitant skin lesions. These components essentially anchor one epithelial cell to another above the basal cell layer. Resulting from this autoimmune attack is an intraepithelial separation immediately above the intact basal layer of cells that remains adherent to the underlying basement membrane zone (BMZ). More recently Cirillo and Prime used a systems biology approach in studying keratinocyte and desmosomal interactions. In their model the adaptor protein, plakophylin 3 is a crucial molecule in mediating the cell-to-cell detachment or dysadhesion induced by PV IgG. The identification of a noncadherin desmosomal protein, perp , which, following PV autoantibody perturbation at the desmosome, is internalized, leading to a deficiency within the desmosome that, in turn, heightens the degradative effects on keratinocytes at their attachment sites. Additionally, the possible role for antibodies directed against the 9 alpha nicotinic acetaldehyde receptor has been reviewed with a possible role for therapeutic alternatives concerning the addition of cholinergic agonists. An apparent event in the pathogenesis of desmosomal loss is that, subsequent to PV IgG attack at the desmosome, there is Dsg 3 endocytosis, followed by a corresponding retraction of keratin filaments toward the keratinocyte nucleus, followed by cell-cell adhesion compromise or loss, and that Dsg 3 internalization is intimately associated with the pathogenic activity of PV IgG activity.

Drug-induced pemphigus may occur uncommonly. Drug classes involved include thiol group agents or those with a sulfhydryl radical (chiefly captopril and other ACE inhibitors) and penicillamine; as well as non-thiol medications, including rifampin, diclofenac, and phenol-containing drugs.

Clinical Findings

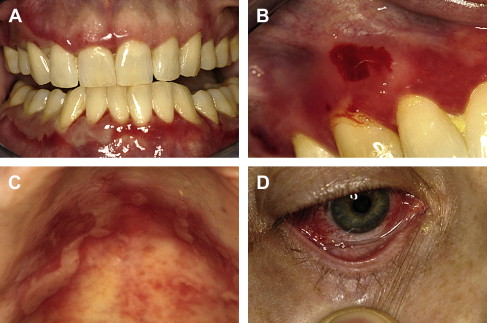

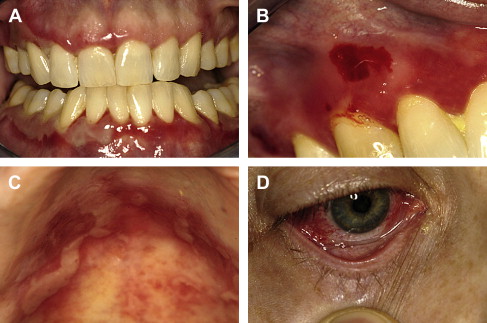

Pemphigus may be seen across a wide age spectrum, though childhood onset is an uncommon event. Most cases are noted to occur in middle-aged to elderly adults. Onset is usually insidious, often masquerading as nonspecific ulcerations that heal within a few weeks with new lesions appearing elsewhere. Lesions are characterized as very short-lived vesicles initially and later, if untreated, bullae. Subsequent to vesicle rupture, tender and painful erosions and ulceration ensue. Palatal, buccal, and labial mucosal sites are favored, though no particular intraoral site is immune from involvement in untreated cases. Gingival involvement is often desquamative or erosive in nature. Oropharyngeal and hypopharyngeal involvement is characterized by odynophagia and hoarseness. Newly ruptured lesions will demonstrate a retracted surface epithelial component immediately adjacent to tender erosions and ulcerations ( Fig. 1 ).

A rare form of pemphigus is paraneoplastic pemphigus, which, as the term implies, is associated with an underlying neoplastic condition, chiefly lymphoreticular in nature, though sarcomas may also be seen as the underlying neoplasm. Lesions may develop before, coincident with, or following the diagnosis of neoplasia. With this condition there is almost always involvement of the labial vermilion surface and skin. Other mucosal sites involved beyond the oral cavity include the trachea and larynx.

Diagnosis

The diagnosis of PV involves routine as well as specific studies designed to characterize tissue alterations as well as to identify pathogenic antibodies, usually in patient tissue obtained by routine mucosal tissue biopsy ( Table 1 ). The necessary step of immunologic verification involves use of a direct immunofluorescence technique in which the patient’s mucosal specimen is paired with labeled or tagged immunoglobulin. Verification of diagnosis or quantification of the degree of antibody concentration or titer is available as indirect immunofluorescence (IIF); patient serum is proportionately diluted and reacted with nonpatient substrate tissue and labeled antihuman immunoglobulin.

| MP | Allergic or hypersensitivity reaction |

| Erosive lichen planus | Lupus erythematosus |

| Erythema multiforme | Epidermolysis bullosa |

| Viral infection | — |

Consideration of the precise site of tissue acquisition is important. Owing to the very friable nature of the oral mucosa in PV and the propensity of the mucosal surface to tear or simply shear away from the surgical blade, it is preferable to sample an area of mucosa that is not obviously involved with PV, but rather at a short distance from clinically evident disease. Therefore, perilesional tissue should be sampled.

Subsequent to obtaining a representative specimen, it must be managed carefully as to preserve the surface integrity. Additionally, the tissue must be placed into 10% neutral buffered formalin, as is routine for standard pathologic assessment, and also must be immersed in Michel’s transport medium or buffer for direct immunofluorescence testing, as formalin-fixed tissue will not preserve the specimen properly for this technique.

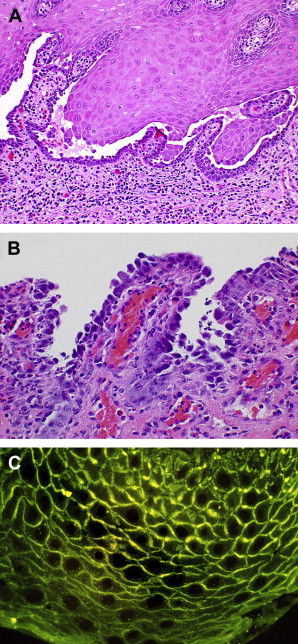

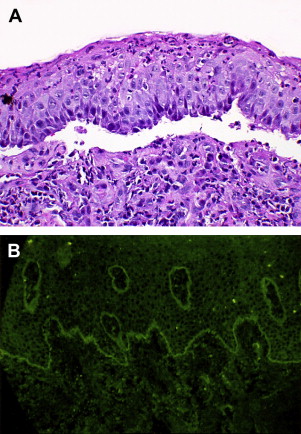

The classic diagnostic light microscopic features of PV include a cleavage or separation of the suprabasal layer of the surface epithelium with the basal layer of cells remaining adherent to the basement region. This layer of cells assumes a so-called “tombstone” quality, while free-floating, acantholytic cells above the basal layer (Tzanck cells) are seen secondary to desmosomal loss and corresponding tonofilament retraction Fig. 2 .

In addition to routine microscopy, direct immunofluorescence (DIF) studies will demonstrate the presence of IgG antibody and activated complement (C-3) along the cell surface within the intercellular space Fig. 2 C. Similarly, IIF studies using the patient’s serum, though less sensitive than DIF, may be used to demonstrate the presence of serum or circulating antibody levels.

An alternative to direct immunofluorescence to demonstrate the presence of intercellular IgG antibodies is through the use of an immunoperoxidase staining technique where the primary antibody is tagged with the peroxidase enzyme that subsequently catalyzes activation of a chromogen at the site of antigen-antibody binding in tissue.

In addition to routine IIF, circulating antibody may also be demonstrated by an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) where great sensitivity has been shown in establishing the diagnosis and response to treatment; although it has been cautioned against as there has been some lack of correlation between disease activity and antibody levels.

Differential Diagnosis

Loss of surface epithelial integrity will also be noted in other conditions that might be similar to PV. These include MP, paraneoplastic pemphigus (PNP), and a rare subset of PV: pemphigus vegetans (Pveg).

In Pveg, skin is predominantly involved with labial vermilion border and oral mucosal lesions, followed later in the course of the disease by an epithelial hyperplasia with corresponding intraepithelial aggregates of large numbers of eosinophils, IgG, and activated complement. MP will demonstrate subepithelial cleavage with IgG and activated complement along the epithelial-connective tissue interface, with the epithelial surface intact. PNP is immunologically and microscopically complex with subepithelial and intraepithelial separations seen on routine microscopy, while a large number of epithelial and basement membrane antigens are targeted.

MP: mucous membrane pemphigoid, cicatricial pemphigoid, and benign mucous membrane pemphigoid

MP represents an additional chronic blistering disease of autoimmune origin, without a particular inciting or triggering stimulus. Clinical involvement may extend to the eye or ocular conjunctival mucosa, or may remain restricted to the oral cavity, with oral disease usually antedating the onset of ocular involvement. A recent study noted a 37% incidence rate of developing ocular disease in cases where oral disease developed initially, with a mean interval of 19.3 months between the diagnosis or oral MP and ocular MP. MP is a member of a group or family of autoimmune subepithelial blistering diseases that includes bullous pemphigoid (BP), gestational pemphigoid, linear IgA disease, epidermolysis bullosa acquisita, and bullous systemic lupus erythematosus; though oral mucosal involvement with those conditions beyond MP is uncommon to rare. MP is considered to be generally heterogeneous in nature with several autoantibodies identified as pathogenic.

Cause and Pathogenesis

The anatomic region of the oral mucosa that is directly affected in terms of cause is the BMZ. This region represents a complex anatomic and macromolecular continuum of proteins derived from the keratinocyte and fibroblast populations of cells that form a functional network of fibrillar proteins and glycoproteins that enable a stable association of surface epithelium and underlying lamina propria and submucosa, across the basement membrane complex. MP represents one such disease state where there is a perturbation of this macromolecular complex by an autoimmune process. As with many autoimmune conditions, the initial or triggering event in producing the disease is unknown, though some drugs may have a role in this process, as is the case with PV. Autoantibodies in MP are predominantly directed against BP 180 and less commonly against laminin 5 (epiligrin), type 7 collagen, or the β4 subunit of α6β4 integrin (a transmembrane keratinocyte-specific integrin), and the a6 integrin subunit. IgG and C3 deposits are usually identified in the basement membrane complex or hemidesmosomes with immunofluorescence techniques, where many distinct antigenic components have been identified overall.

The actual mechanisms of epithelial separation or dysadhesion from the lamina propria may occur in a variety of ways. Subsequent to the binding of autoantibodies to target antigens within the BMZ complement, activation follows with release of chemoattractants and subsequent recruitment of eosinophils and neutrophils. Proteolysis follows, along with further release of chemoattractants and cytokines, with ultimate focal tissue damage and epithelial-subepithelial dysadhesion. A second mechanism by which the same tissue effect will evolve is by direct interference with the function of adhesion of BP 180, laminin 5 (epiligrin), or integrins (chiefly α6β4). There is a secondary disassembly of hemidesmosomes resulting in defective adhesion and separation. Finally, there may be a resultant defect in cell signaling followed by disturbed hemidesmosome assembly and induction of proinflammatory cytokines contributing to epithelial-subepithelial separation or dysadhesion.

Clinical Findings

MP may arise initially at any mucosal site, including oral and conjunctival mucosa most commonly, but also the external genitalia, anus, and upper gastrointestinal tract or esophagus. Of note, however, is that 85% of cases will have oral involvement without concomitant skin involvement, and it may be the only site of disease.

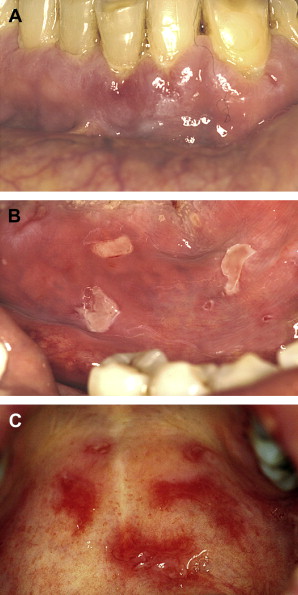

Lesions distribution will chiefly involve the gingiva, palatal mucosa, and buccal mucosa; and less over the tongue, alveolar ridges and lips ( Fig. 3 A–C ). The gingival presentation is typically one of painful erythematous and tender erosions with desquamation, either spontaneously or with very minimal physical trauma, such as with tooth brushing. Often there is an inability to maintain oral care with consequent heavy accumulation of plaque and an additional inflammatory burden from this source. Small vesicles may be observed that rupture easily, but, in comparison to those of PV, are longer-lasting and more well-defined. With rupture of vesicles, tender erosions result along with functional discomfort. Over time, there may be scarring (cicatrization) at sites of repeated vesiculo-erosive lesion development and healing, chiefly over the posterior soft palate, uvula, tonsillar folds, ventral tongue, and floor of the mouth.

Establishment of this diagnosis is often in the dental office, given the frequency of initial oral mucosal presentation. Subsequent to diagnosis and in association with initial treatment of oral lesions, patients must be evaluated by an ophthalmologist, as conjunctival involvement is common and may result in corneal damage and possible blindness if untreated Fig. 3 D. In cases where pharyngeal involvement is present, an evaluation with a gastroenterologist is indicated. Additionally, in cases where there may be epistaxis, nasal crusting, and mucosal adhesions, an otolaryngologist must be consulted.

Diagnosis

Routine microscopic evaluation of either an intact vesicle or perilesional tissue will signal the presence of a clear subepithelial separation in the absence of acantholysis, as the site of antigen-antibody interaction is below the basal epithelial layer Fig. 4 A . Absence of basal cell adhesion to the lamina propria will be noted, as will a monocellular inflammatory infiltrate with lymphocytes and plasma cells in evidence. Ultrastructural examination, although not a routine study, will show a separation within the lamina lucida.

Key to the establishment of the diagnosis of MP and its separation from other vesiculo-erosive conditions is the performance of direct immunofluorescence microscopy, where the patient’s mucosal tissue is treated with fluorescein-labeled antihuman immunoglobulin for demonstration of in vivo-bound immunoglobulin. Most cases (up to 90%) will show the presence of IgG or C3 in a smooth and linear pattern along the basement membrane Fig. 4 B. Less commonly, there may be linear deposits of IgA and IgM in the same pattern.

Other studies to demonstrate the pathognomonic features of MP, although not routine, include immunoelectron microscopy, as well as immunochemical modalities involving immunoprecipitation and immunoblotting. High sensitivity and specificity in searching for circulating autoantibodies are possible with the use of recombinant proteins, such as BP 180, by ELISA testing.

The use of laser canning confocal microscopy has been advocated recently for diagnostic distinction among subepithelial blistering diseases by way of detecting the presence and precise location of in vivo-bound immunoglobulin within the patient’s tissue.

Differential Diagnosis

Distinguishing MP from other subepithelial blistering and erosive diseases that may involve mucosa where there may be immune deposits along the basement membrane region may prove difficult. The wide spectrum of autoimmune blistering diseases that can manifest within the area of the basement membrane include BP, linear IgA disease, and epidermolysis bullosa acquisita. In the oral cavity in particular, MP must be chiefly separated from PV and erosive LP. The presence of scarring may help separate MP from these; however, in the early phases of the disease, scarring may not be easily seen or present.

MP: mucous membrane pemphigoid, cicatricial pemphigoid, and benign mucous membrane pemphigoid

MP represents an additional chronic blistering disease of autoimmune origin, without a particular inciting or triggering stimulus. Clinical involvement may extend to the eye or ocular conjunctival mucosa, or may remain restricted to the oral cavity, with oral disease usually antedating the onset of ocular involvement. A recent study noted a 37% incidence rate of developing ocular disease in cases where oral disease developed initially, with a mean interval of 19.3 months between the diagnosis or oral MP and ocular MP. MP is a member of a group or family of autoimmune subepithelial blistering diseases that includes bullous pemphigoid (BP), gestational pemphigoid, linear IgA disease, epidermolysis bullosa acquisita, and bullous systemic lupus erythematosus; though oral mucosal involvement with those conditions beyond MP is uncommon to rare. MP is considered to be generally heterogeneous in nature with several autoantibodies identified as pathogenic.

Cause and Pathogenesis

The anatomic region of the oral mucosa that is directly affected in terms of cause is the BMZ. This region represents a complex anatomic and macromolecular continuum of proteins derived from the keratinocyte and fibroblast populations of cells that form a functional network of fibrillar proteins and glycoproteins that enable a stable association of surface epithelium and underlying lamina propria and submucosa, across the basement membrane complex. MP represents one such disease state where there is a perturbation of this macromolecular complex by an autoimmune process. As with many autoimmune conditions, the initial or triggering event in producing the disease is unknown, though some drugs may have a role in this process, as is the case with PV. Autoantibodies in MP are predominantly directed against BP 180 and less commonly against laminin 5 (epiligrin), type 7 collagen, or the β4 subunit of α6β4 integrin (a transmembrane keratinocyte-specific integrin), and the a6 integrin subunit. IgG and C3 deposits are usually identified in the basement membrane complex or hemidesmosomes with immunofluorescence techniques, where many distinct antigenic components have been identified overall.

The actual mechanisms of epithelial separation or dysadhesion from the lamina propria may occur in a variety of ways. Subsequent to the binding of autoantibodies to target antigens within the BMZ complement, activation follows with release of chemoattractants and subsequent recruitment of eosinophils and neutrophils. Proteolysis follows, along with further release of chemoattractants and cytokines, with ultimate focal tissue damage and epithelial-subepithelial dysadhesion. A second mechanism by which the same tissue effect will evolve is by direct interference with the function of adhesion of BP 180, laminin 5 (epiligrin), or integrins (chiefly α6β4). There is a secondary disassembly of hemidesmosomes resulting in defective adhesion and separation. Finally, there may be a resultant defect in cell signaling followed by disturbed hemidesmosome assembly and induction of proinflammatory cytokines contributing to epithelial-subepithelial separation or dysadhesion.

Clinical Findings

MP may arise initially at any mucosal site, including oral and conjunctival mucosa most commonly, but also the external genitalia, anus, and upper gastrointestinal tract or esophagus. Of note, however, is that 85% of cases will have oral involvement without concomitant skin involvement, and it may be the only site of disease.

Lesions distribution will chiefly involve the gingiva, palatal mucosa, and buccal mucosa; and less over the tongue, alveolar ridges and lips ( Fig. 3 A–C ). The gingival presentation is typically one of painful erythematous and tender erosions with desquamation, either spontaneously or with very minimal physical trauma, such as with tooth brushing. Often there is an inability to maintain oral care with consequent heavy accumulation of plaque and an additional inflammatory burden from this source. Small vesicles may be observed that rupture easily, but, in comparison to those of PV, are longer-lasting and more well-defined. With rupture of vesicles, tender erosions result along with functional discomfort. Over time, there may be scarring (cicatrization) at sites of repeated vesiculo-erosive lesion development and healing, chiefly over the posterior soft palate, uvula, tonsillar folds, ventral tongue, and floor of the mouth.