Introduction

This systematic review evaluated root resorption as an outcome for patients who had orthodontic tooth movement. The results could provide the best available evidence for clinical decisions to minimize the risks and severity of root resorption.

Methods

Electronic databases were searched, nonelectronic journals were hand searched, and experts in the field were consulted with no language restrictions. Study selection criteria included randomized clinical trials involving human subjects for orthodontic tooth movement, with fixed appliances, and root resorption recorded during or after treatment. Two authors independently reviewed and extracted data from the selected studies on a standardized form.

Results

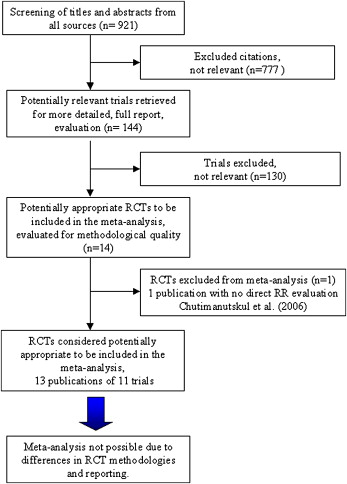

The searches retrieved 921 unique citations. Titles and abstracts identified 144 full articles from which 13 remained after the inclusion criteria were applied. Differences in the methodologic approaches and reporting results made quantitative statistical comparisons impossible. Evidence suggests that comprehensive orthodontic treatment causes increased incidence and severity of root resorption, and heavy forces might be particularly harmful. Orthodontically induced inflammatory root resorption is unaffected by archwire sequencing, bracket prescription, and self-ligation. Previous trauma and tooth morphology are unlikely causative factors. There is some evidence that a 2 to 3 month pause in treatment decreases total root resorption.

Conclusions

The results were inconclusive in the clinical management of root resorption, but there is evidence to support the use of light forces, especially with incisor intrusion.

At present, it is unknown how orthodontic treatment factors influence root resorption (RR). The etiologic factors are complex and multifactorial, but it appears that apical RR results from a combination of individual biologic variability, genetic predisposition, and the effect of mechanical factors. RR is undesirable because it can affect the long-term viability of the dentition, and reports in the literature indicate that patients undergoing orthodontic treatment are more likely to have severe apical root shortening. Patient factors such as genetics and external factors including trauma are also thought to be associated with increased RR.

Many general dentists and other dental specialists believe that RR is avoidable and hold the orthodontist responsible when it occurs during orthodontic treatment. It is therefore important to identify which orthodontic treatment factors contribute to RR, so that the detrimental effects can be minimized and RR reduced.

Histologic studies reported greater than a 90% occurrence of orthodontically induced inflammatory RR (OIIRR) in orthodontically treated teeth. Lower percentages were reported with diagnostic radiographic techniques. Lupi and Linge reported the incidence of external apical RR (EARR) at 15% before treatment and 73% after treatment. In most cases, the loss of root structure was minimal and clinically insignificant.

With panoramic or periapical radiographs, OIIRR is usually less than 2.5 mm, or varying from 6% to 13% for different teeth. By using graded scales, OIIRR is usually classified as minor or moderate in most orthodontic patients. Severe resorption, defined as exceeding 4 mm, or a third of the original root length, is seen in 1% to 5% of teeth.

Regardless of genetic or treatment-related factors, the maxillary incisors consistently average more apical RR than any other teeth, followed by the mandibular incisors and first molars.

Orthodontic treatment-related risk factors include treatment duration, magnitude of applied force, direction of tooth movement, amount of apical displacement, and method of force application (continuous vs intermittent, type of appliance, and treatment technique ).

Individual susceptibility is considered a major factor in determining RR potential with or without orthodontic treatment. Patient-related risk factors include: previous history of RR ; tooth-root morphology, length, and roots with developmental abnormalities ; genetic influences ; systemic factors including drugs (nabumetone), hormone deficiency, hypothyroidism, hypopituitarism ; asthma ; root proximity to cortical bone ; alveolar bone density ; chronic alcoholism ; previous trauma ; endodontic treatment ; severity and type of malocclusion ; patient age ; and sex.

Several reviews and a meta-analysis examined orthodontics and RR. However, they were not systematic in nature, and the meta-analysis utilized only a Medline search, was restricted to the English language and central incisors, and included retrospective, nonrandomized controlled trials. This systematic review was designed to be more comprehensive in the search method and more restrictive regarding quality measures. It was expected that variables relating orthodontic treatment to RR would be identified. By combining the results from clinical trials, we believed that a stronger evidence-based approach to RR associated with orthodontic tooth movement would provide important guidelines for contemporary clinical practice.

The purpose of this article was to report the results from a rigorous systematic review of scientific literature that relates EARR in patients with fixed orthodontic appliances.

Material and methods

The first phase of the meta-analysis involved the development of a specific protocol and research question. Table I outlines the Population Intervention Control Outcome (PICO) format used and the null hypotheses. The methods for this review were based on the guidelines of the Cochrane Database of systematic reviews. The primary objective of this review was to evaluate the effect of orthodontic treatment on RR. The secondary objective was to examine the effects of systemic conditions and specific orthodontic mechanics on the rate and severity of RR.

| PICO format | |

| Population | Patients with no history of RR |

| Intervention | Comprehensive orthodontics |

| Comparison | People who did not have orthodontic treatment; no teeth were moved orthodontically |

| Outcome | EARR |

| Null hypotheses | |

| 1. There is no difference in the incidence and severity of RR between patients, with no history of RR, undergoing comprehensive orthodontic treatment and subjects not treated orthodontically. | |

| 2. There is no difference in the incidence and severity of RR between patients, with no history of RR, undergoing comprehensive orthodontic treatment whose teeth are moved with different techniques. | |

For this review, we located citations to relevant trials in journals, dissertations, and conference proceedings by searching appropriate databases. Detailed search strategies were developed for each database used to identify studies (published and unpublished) to be considered for inclusion. Table II lists the databases searched in this review. To locate additional studies, reference lists of review articles and all included studies were checked. Requests were also sent to relevant professional organizations to identify unpublished and ongoing studies. Hand searches were undertaken to locate published material not indexed in available databases.

| Databases of published trials |

| MEDLINE searched via PubMed (1950-October 2008) |

| EMBASE searched via www.embase.com (1974-October 2008) |

| Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (Cochrane Reviews) searched via The Cochrane Library (October 2008) |

| Cochrane Cental Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL) searched via The Cochrane Library (October 2008) |

| Cochrane Oral Health Group Trials Register searched via The Cochrane Library (October 2008) |

| WEB OF SCIENCE searched via www.isiknowledge.com (1975- October 3 rd 2008) |

| EBM Reviews (Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, ASP Journal Club, DARE, and CCTR) searched via www.ovid.com (1991- October 2008) |

| Computer Retrieval of Information on Scientific Project searched via www.crisp.cit.nih.gov (1978 – October 2008) |

| On-Line Computer Library Center searched via www.oclc.org/home (1967- October 2008) |

| Google Index to Scientific and Technical Proceedings searched via www.isinet.com/isi/products/indexproducts/istp (October 2008) |

| LILACS (Latin American and Caribbean Center on Health Sciences Information) searched via www.bireme.br/local/Site/bireme/I/homepage.htm (1982 to October 2008) |

| PAHO searched via www.paho.org to October 3 rd 2008 |

| WHOLis searched via www.who.int/library/databases/en to October 3rd 2008 |

| BBO (Brazilian Bibliography of Dentistry) searched via bases.bireme.br/cgibin/wxislind.exe/iah/online (1966-October 2008) |

| CEPS (Chinese Electronic Periodical Services) searched via www.airiti.com/ceps/ec_en/ to October 3 rd 2008 |

| Databases of dissertations and conference proceedings |

| Conference materials searched via www.bl.uk/services/bsds/dsc/conference.html ; October 3, 2008 |

| Cochrane Cental Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL) searched via the Cochrane Library (October 2008) |

| ProQuest Dissertation Abstracts and Thesis database searched via www.lib.umi.com/dissertations (1986 to October 2008) |

| Databases of research registers |

| TrialCentral searched via www.trialscentral.org on October 3, 2008 |

| National Research Register (United Kingdom) searched via www.controlled-trials.com (1998-October 2008) |

| www.Clinicaltrials.gov , October 3, 2008 |

| Grey literature |

| SIGLE (System for Information on Grey Literature in Europe) searched via http://opensigle.inist.fr/ , 1980 to October 2005 |

No restrictions were placed on year, publication status, or language of the trials. Translations of foreign-language articles were obtained by contacts in the College of Dentistry at Ohio State University.

Two reviewers (B.W. and K.W.L.V.) independently examined and coded the studies that were identified by the above methods. Trials appropriate to be included in the review were randomized controlled trials (RCTs) fulfilling certain criteria concerning study design, participant characteristics, intervention characteristics, RR outcome, and comparison group. Details about the selection criteria are given in Table III .

| Criteria category | Definition |

|---|---|

| Study design | Trials should be RCTs (published or unpublished) comparing root length before and during or after treatment in human subjects; split-mouth trials were eligible if randomization was used. |

| Participants | Trials included could involve subjects or teeth in the same person of any age, sex, or ethnicity who had orthodontic treatment with fixed appliances. |

| Intervention | Trials could involve interventions of continuous vs noncontinuous forces, differing directions of tooth movement, light vs heavy forces, differing durations of treatment, differing distances of tooth movement, different types of orthodontic appliances. |

| Control | Trials could involve patients or teeth in the same subject (including the split-mouth technique) not subjected to orthodontic force either through a placebo, bracket placement but no activation, or absence of intervention. |

| Outcome | Trials included should record the presence or absence of EARR by treatment group at the end of the treatment period. |

| Secondary outcomes include the severity and extent of RR between experimental and control groups assessed either directly with histology or indirectly with a radiograph technique, and patient-based outcomes such as perception of RR, further complications (mobility, tooth loss), and quality-of-life data. |

The same reviewers extracted data independently, using specially designed data-extraction forms, which were piloted on several articles and modified as required. Any disagreement was discussed and a third reviewer consulted when necessary. All authors were contacted for clarification of missing information. Data were excluded until further clarification became available or if agreement could not be reached. All studies meeting the inclusion criteria then underwent validity assessment and data extraction. Studies rejected at this or subsequent stages were recorded, with the reasons for exclusion listed.

The 2 reviewers evaluated the quality of the trials included in the review independently by assessing 4 main criteria: method of randomization, allocation concealment, blinding of outcome assessors, and completeness of follow-up. Additional minor criteria were examined, including baseline similarity of the groups, reporting of eligibility criteria, measure of the variability of the primary outcome, and sample size calculation. Details about the assessment criteria are given in Table IV .

| Component | Classification | Definition |

|---|---|---|

| Four main quality criteria | ||

| 1. Method of randomization (Altman et al ) | Adequate | Any random sequence satisfying the CONSORT criteria. |

| Inadequate | Alternate assignment, case record number, dates of birth. | |

| Unclear | Just the term randomized or randomly allocated without further elaboration of the exact methodology in the text and unable to clarify with the author. | |

| 2. Allocation concealment (Pildal et al ) | Adequate | Central randomization, opaque sealed sequentially numbered envelopes, numbered coded vehicles implicitly or explicitly described containing treatment in random order. |

| Inadequate | Allocation by alternate assignment, case record number, dates of birth, or open tables of random numbers. | |

| Unclear | No reported negation of disclosing participants’ prognostic data to central office staff before clinician obtains treatment assignment; no reported information on whether allocation sequence is concealed to central staff before a participant is irreversibly registered and no assurance that the sequence is strictly sequentially administered. Unclear in the text and unable to clarify with the author. | |

| Not used | No method of allocation concealment used. | |

| 3. Blinding of outcome assessors | Yes | Outcome assessors did not know which group to which the participants were randomized. |

| No | Outcome assessors could assume to which group the participant had been randomized. | |

| Unclear | Unclear in the text and unable to clarify with the author. | |

| 4. Completeness to follow-up (Altman et al ) | Yes | Numbers in the methods and results were the same or not the same but with all dropouts explained. |

| No | Numbers in the methods and results were not the same, and dropouts were not explained. | |

| Unclear | Unclear in the text and unable to clarify with the author. | |

| Minor criteria | ||

| 1. Baseline similarity of groups | Yes | |

| No | Groups were not similar at baseline; no comparison between groups at baseline was made. | |

| Unclear | Unclear in the text and unable to clarify with the author. | |

| 2. Reporting of eligibility criteria | Yes | |

| No | No clear eligibility criteria. | |

| Unclear | Unclear in the text and unable to clarify with the author. | |

| 3. Measure of variability of primary outcome | Yes | |

| No | ||

| Unclear | Unclear in the text and unable to clarify with the author. | |

| 4. Sample size calculation | Yes | |

| No | Sample size calculation was not done. | |

| Unclear | Unclear in the text and unable to clarify with the author. |

Statistical analysis

To assess reviewer agreement with respect to the methodologic quality, a kappa statistic was calculated. One reviewer entered that data into Review Manager (version 5.0, Cochrane Collaboration, Boston, Mass).

Quantitative synthesis of data from many studies was to be carried out according to the procedures recommended by the Cochrane Collaboration.

Results

The electronic and hand searches retrieved 921 unique citations, which were entered into a QUORUM flow chart ( Fig ) to illustrate the path for selecting the final trials. After evaluating titles and abstracts, 144 full articles were obtained (2 articles could not be located). After evaluating the full texts and querying primary authors, we determined that 13 articles, describing 11 trials, fulfilled the criteria for inclusion. Summary details of the studies examined are recorded in Table V . Because these studies used different methodologies and reporting strategies, it was impossible to undertake a quantitative synthesis. A qualitative analysis is therefore presented; it excluded retrospective studies because these are observational and could have been subject to selection bias. Although there are many statistical methods to minimize selection bias, no method unequivocally eliminates it. Thus, retrospective studies (even well-designed ones) do not provide comparative evidence equivalent to that of randomized trials. We chose to include this information in our review by informally comparing the results of the randomized trials to those of key observational studies in our discussion.

| Study | Acar et al |

| Methods | RCT; split-mouth design |

| Participants | 22 first premolars from 8 patients; ages, 15-23 y; 6 control patients, ages, 14-20 y |

| Interventions | Continuous and discontinuous 100-g force application |

| Outcomes | Extracted premolars—composite electron micrographs were digitized and amount of root resorbed area calculated, visual assessment of apical morphology and EARR severity. |

| Notes | 9-week treatment period, no withdrawals, no assessor blinding |

| Allocation concealment | Unclear |

| Study | Barbagallo et al |

| Methods | RCT; split-mouth design |

| Participants | 54 maxillary first premolars from 27 patients, 15 female, 12 male; ages, 12.5-20 y; mean, 15.3 y |

| Interventions | TA vs control, TA vs 225-g continuous force, TA vs 25-g continuous force |

| Outcomes | Extracted premolars—x-ray microtomography measuring the amount of RR in cubed root volume. |

| Notes | 8-week treatment period, no withdrawals, no assessor blinding |

| Allocation concealment | No |

| Study | Brin et al |

| Methods | RCT; retrospective collection of original data |

| Participants | 138 children with Class II Division 1 malocclusions (overjet >7 mm) |

| Interventions | 1-phase treatment vs phase 1 with headgear or bionator followed by phase 2 treatment of comprehensive orthodontics |

| Outcomes | Length of treatment, trauma, root development/timing of treatment, EARR, root morphology |

| Notes | Withdrawals accounted for, adequate assessor blinding |

| Allocation concealment | Computer randomization, e-mailed to research associate |

| Study | Chan and Darendeliler |

| Methods | RCT; split-mouth design |

| Participants | 20 maxillary first premolars from 10 patients, intraindividual controls |

| Interventions | Light (25 g) or heavy (225 g) continuous force vs control |

| Outcomes | Extracted premolars—volumetric measurement of RR craters via scanning electron microscope, measured in mean volume x 10 5 μm 3 |

| Notes | 4-week treatment period, no withdrawals, no assessor blinding |

| Allocation concealment | No |

| Study | Chan and Darendeliler |

| Methods | RCT; split-mouth design |

| Participants | 36 premolars in 16 patients, 10 boys, 6 girls; ages, 11.7-16.1 y; mean, 13.9 y; intraindividual controls |

| Interventions | Light (25 g) or heavy (225 g) continuous force vs control |

| Outcomes | Extracted premolars—volumetric measurement of RR craters via scanning electron microscope, measured in mean volume x 10 6 μm 3 , and to quantify by volumetric measurements the extent of RR in areas under compression and tension |

| Notes | 4-week treatment period, no withdrawals, no assessor blinding |

| Allocation concealment | No |

| Study | Han et al |

| Methods | RCT; split-mouth design |

| Participants | 18 maxillary first premolars from 9 patients, 5 female, 4 male; ages, 12.7-20 y; mean, 15.3 y; 11 control teeth were obtained from 6 randomly selected patients aged 12-20 y |

| Interventions | Intrusion vs extrusion via 100-g continuous force |

| Outcomes | Extracted premolars—RR area was calculated as percentage of total root area via scanning electron microscope and visually assessed qualitatively |

| Notes | 8-week treatment period, control teeth extracted before orthodontic treatment, no withdrawals, observers were blinded |

| Allocation concealment | Yes, randomization computer program, results mailed to operator |

| Study | Harris et al |

| Methods | RCT; split-mouth design |

| Participants | 54 maxillary first premolars from 27 patients, 12 boys, 15 girls; ages, 11.9-19.3 y; mean, 15.6 y |

| Interventions | Heavy (225 g) continuous force vs control; light (25 g) continuous force vs control; light (25 g) vs heavy (225 g) continuous force |

| Outcomes | Extracted premolars—volumetric assessment of RR crater magnitude and location |

| Notes | 4-week treatment period, no withdrawals, no assessor blinding |

| Allocation concealment | No |

| Study | Levander et al |

| Methods | RCT |

| Participants | 40 patients, 62 maxillary incisors, with initial RR during orthodontics, 15 boys, 25 girls; ages, 12-18 y; mean, 15 y |

| Interventions | Planned treatment vs 2-3 month discontinuation of orthodontic treatment and then planned treatment |

| Outcomes | Periapical radiographic assessment of maxillary incisor root length |

| Notes | Patients randomized 6 months into treatment after identification of RR, no withdrawals |

| Allocation concealment | Unclear |

| Study | Mandall et al |

| Methods | RCT—throwing an unweighted die, block randomization |

| Participants | 154 patients, ages, 10-17 y, randomized 6 months into treatment after identification of RR, no withdrawals |

| Interventions | 3 different archwire sequences |

| Outcomes | Patient discomfort at each wire change and in total, RR (root length) of maxillary left central incisor assessed by periapical radiography, time to reach maxillary and mandibular working archwire (0.019 x 0.025-in stainless steel) in months, number of patient visits |

| Notes | All withdrawals accounted for, blinded assessors for RR |

| Allocation concealment | Adequate—opaque envelopes |

| Study | Reukers et al |

| Methods | RCT—balanced treatment allocation via computer |

| Participants | 149 Class II patients, 64 male, 85 female; mean age, 12 y 4 mo (SD, 1 y 2 mo); range, 10 y 7 mo-15 y 8 mo |

| Interventions | Fully programmed edgewise (straight wire) vs partly programmed (conventional) edgewise |

| Outcomes | Prevalence and degree of RR seen via periapical radiography via a bisecting angle technique. |

| Notes | All withdrawals accounted for, blinded assessors for RR |

| Allocation concealment | Adequate—orthodontist informed by central trial registration |

| Study | Scott et al |

| Methods | RCT—balanced treatment allocation via restricted number table |

| Participants | 62 patients, 32 male, 30 female; mean age, 16.27 y, with mandibular irregularities of 5-12 mm, requiring mandibular first premolar extractions |

| Interventions | Damon3 self-ligating brackets vs Synthesis (Roth prescription) conventionally ligated brackets |

| Outcomes | Rapidity of tooth alignment; changes in root length; changes in arch dimension, measured via lateral cephalograms and long-cone periapical radiographs |

| Notes | All withdrawals accounted for, blinded assessor for RR, 95% power |

| Allocation concealment | Unclear |

Methodologic quality

The assessments for the 4 main methodologic quality items are shown in Table VI . A study was assessed to have a high risk of bias if it did not receive a “yes” in 3 or more of the 4 main categories, a moderate risk if 2 of the 4 did not receive a “yes,” and a low risk if randomization, assessor blinding, and completeness of follow-up were considered adequate.

| Study | Randomization | Allocation concealed | Assessor blinding | Dropouts described | Risk of bias |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Acar et al | No | Unclear | Unclear | Yes | High |

| Barbagallo et al | Yes | No | No | Yes | Moderate |

| Brin et al | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Low—retrospective |

| Chan and Darendeliler | Yes | No | No | Yes | Moderate |

| Chan and Darendeliler | Yes | No | No | Yes | Moderate |

| Han et al | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Low |

| Harris et al | Yes | No | No | Yes | Moderate |

| Levander et al | Yes | Unclear | Unclear | Yes | Moderate |

| Mandall et al | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Low |

| Reukers et al | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Low |

| Scott et al | Yes | Unclear | Yes | Yes | Low |

After examination of the studies and follow-up contacts with the authors, if necessary and as noted in Table VI , the method of randomization was considered adequate for 10 of the 11 trials, but the method of allocation concealment was adequate in only 4 of these. The method of randomization and allocation concealment were inadequate or unclear for the remaining 7 articles. Blinding for outcome evaluation was reported in 5 trials. The reporting and analysis of withdrawals and dropouts was considered adequate in all 11 trials. Five studies were assessed to have low risk of bias, 5 had moderate risk of bias, and 1 had the potential for a high risk of bias.

The minor methodologic quality criteria examined are shown in Table VII . Six studies fulfilled all the minor methodologic quality criteria. Sample size was justified in 6 of the 11 trials. Five studies made comparisons to assess the comparability of the experimental and control group at baseline. Four studies were considered comparable at baseline because they had a split-mouth design with intraindividual controls. Comparability at baseline for Han et al was considered adequate since there was an intraindividual control for the experimental groups, and control teeth were randomly selected (same age and orthodontic treatment plan as the experimental subjects). The study by Acar at al was not comparable at baseline because there was an intraindividual control for both experimental groups, but the control teeth were not randomly selected (same age and orthodontic treatment plan as the experimental subjects). Ten studies had clear inclusion and exclusion criteria. All studies estimated measurement error.

| Study | Sample justified (size) | Baseline comparison | I/E criteria | Method error |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Acar et al | No | No | Unclear | Yes |

| Barbagallo et al | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Brin et al | No | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Chan and Darendeliler | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Chan and Darendeliler | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Han et al | No | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Harris et al | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Levander et al | No | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Mandall et al | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Reukers et al | Unclear | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Scott et al | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

The kappa scores and percentage agreements between the 2 raters assessing the major methodologic qualities of the studies were the following: randomization 1.0, 100%; concealment 0.72, 82%; blinding 0.91, 95%; and withdrawals 1.0, 100%.

The included studies were grouped into 11 comparisons according to the clinical questions of interest.

Discontinuous vs continuous force

Acar et al compared a 100-g force with elastics in either an interrupted (12 hours per day) or a continuous (24 hours per day) application. Teeth experiencing orthodontic movement had significantly more RR that control teeth. Continuous force produced significantly more RR than discontinuous force application.

We have some reservations about the reliability of this study’s results and were unable to contact the original author to clarify the methodology; based on the information available, the risk of bias was judged to be high. It only met 1 major and 1 minor methodologic criteria.

Removable thermoplastic appliance vs fixed light and heavy force

Barbagallo et al compared forces applied with removable thermoplastic appliances (TA) and fixed orthodontic appliances. The results showed that teeth experiencing orthodontic movement had significantly more RR than did the control teeth. Heavy force (225 g) produced significantly more RR (9 times greater than the control) than light force (25 g) (5 times greater than the control) or TA force (6 times greater than the control) application. Light force and TA force resulted in similar RR cemental loss.

This study was judged to have a moderate risk of bias, since patients were randomly allocated to the experimental and control groups, but the allocation was not concealed and the assessors not blinded to treatment groups. All minor methodologic criteria were met.

Light vs heavy continuous forces

Four split-mouth studies from the same research group compared fixed orthodontic light (25 g) continuous force with fixed heavy (225 g) continuous force in patients needing premolar extractions to relieve crowding or overjet. Three studies applied a buccal tipping force, and 1 used an intrusive force.

With the exception of a light-force group in a study by Chan and Darendeliler, all teeth experiencing orthodontic movement had significantly more RR than the control teeth. Chan and Darendeliler found the mean volume of the resorption craters in the light-force group was 3.49 times greater than in the control group (not significant). All studies found that heavy forces produced significantly more RR than light forces or controls. Chan and Darendeliler found that the mean volume of the resorption craters was 11.59 times greater in the heavy-force group than in the control group (significant). Heavy forces in both compression and tension areas produced significantly more RR than in regions under light compression and light tension forces.

Barbagallo et al also found that heavy force produced significantly more RR (9 times greater than the control) than light force (5 times greater than the control).

In contrast to the other studies in this section, Harris et al administered intrusive forces. The results showed that the volume of RR craters after intrusion was directly proportional to the magnitude of the intrusive force. A statistically significant trend of linear increase in the volume of the RR craters was observed from control to light (2 times increased) to heavy (4 times increased) groups.

All 4 studies were judged to have a moderate risk of bias, since only 2 major methodologic criteria were met. All minor methodologic criteria were met.

Intrusive vs extrusive force

Han et al found that RR from extrusive force was not significantly different from the control group. Intrusive force significantly increased the percentage of resorbed root area (4 fold). The correlation between intrusion or extrusion and RR in the same patient was r = 0.774 ( P = 0.024).

This study was judged to have a low risk of bias because all major methodologic criteria were met. Minor methodologic criteria, except sample size calculation, were met.

As mentioned previously, Harris et al found that the volume of RR craters after intrusion was directly proportional to the magnitude of the intrusive force. This study was judged to have a moderate risk of bias.

Archwire sequence

Mandall et al compared 3 orthodontic archwire sequences in terms of patient discomfort, RR, and time to working archwire. All patients were treated with maxillary and mandibular preadjusted edgewise appliances (0.022-in slot), and all archwires were manufactured by Ormco (Amersfoort, The Netherlands). The results showed no statistically significant difference between archwire sequences, for maxillary left central incisor RR (F ratio, P = 0.58). There was also no statistically significant difference between the proportion of patients with and without RR between archwire sequence groups (chi-square = 5, P = 0.8, df = 2). This study was well designed and considered unlikely to have significant bias. It was the only study to fulfill all methodologic quality assessment criteria.

Effect of a treatment pause in patients experiencing OIRR

Levander et al investigated the effect of a pause in active treatment on teeth that had experienced apical RR during the initial 6-month period with fixed appliances. All patients were treated with edgewise 0.018-in straight-wire appliances. The results showed that the amount of RR was significantly less in patients treated with a pause (0.4 ± 0.7 mm) than in those treated with continuous forces without a pause (1.5 ± 0.8 mm). No statistically significant correlations were found between RR and Angle classification, trauma history, extraction treatment, time with rectangular archwires, time with Class II elastics, or total treatment time. The study was rated as having a moderate risk of bias, because it fulfilled only 2 major criteria, and there was no a priori sample size calculation. We were unable to contact the author to clarify the allocation concealment and assessor blinding.

Straight wire vs standard edgewise

Reukers et al compared the prevalence and severity of RR after treatment with a fully programmed edgewise appliance (FPA) and a partly programmed edgewise appliance (PPA). All FPA patients were treated with 0.022-in slot Roth prescription (“A” Company, San Diego, Calif), and misplaced brackets were rebonded. All PPA patients were treated with 0.018-in slot Microloc brackets (GAC, Central Islip, NY), and the archwires were adjusted for misplaced brackets. Results showed no statistically significant differences in the amount of tooth root loss (FPA, 8.2%; PPA, 7.5%) or prevalence of RR (FPA, 75%; PPA, 55%) between the groups. This study was well designed and considered unlikely to have significant bias, but it involved variations of 2 variables—slot size and appliance programming—so there could have been undetected interactions.

Trauma vs no trauma

Three studies evaluated the effect of previous trauma (but not EARR) on OIIRR during orthodontic treatment.

Brin et al showed that incisors with clinical signs or patient reports of trauma had essentially the same prevalence of moderate to severe OIIRR as those without trauma. Mandall et al reported no evidence of incisor trauma and RR. Levander et al also showed no statistically significant correlations between RR and trauma history.

The studies by Brin et al and Mandall et al were judged to have low risk of bias, whereas that of Levander et al was judged to have moderate risk of bias.

Teeth with unusual morphology

Brin et al examined the severity of RR in teeth with unusual morphology. The results showed that teeth with roots having unusual morphology before treatment were not significantly more likely to have moderate to severe OIIRR than those with more normal root forms. This study was judged to have a low risk of bias because it fulfilled all major methodologic criteria. However, there was no a priori sample size calculation, since this was a secondary endpoint for the RCT.

Two-phase vs 1-phase Class II treatment

Brin et al examined the effect of 2-phase vs 1-phase Class II treatment on the incidence and severity of RR. The results showed that children treated in 2 phases with a bionator followed by fixed appliances had the fewest incisors with moderate to severe OIIRR, whereas children treated in 1 phase with fixed appliances had the most resorption. However, the difference was not statistically significant. As treatment time increased, the odds of OIIRR also increased ( P = 0.04). The odds of a tooth experiencing severe RR were greater with a large reduction in overjet during phase 2. This study was judged to have a low risk of bias because it fulfilled all major methodologic criteria. There was no a priori sample size calculation, since this was a secondary endpoint for the RCT.

Self-ligating vs conventional orthodontic bracket systems

Scott et al investigated the effect of either Damon3 self-ligating brackets or a conventional orthodontic bracket system on mandibular incisor RR. Patients were treated with Damon3 self-ligating or Synthesis (both, Ormco, Glendora, Calif) conventionally ligated brackets with identical archwires and sequencing in all patients. The results showed that mandibular incisor RR was not statistically different (Damon3, 2.26 mm, SD 2.63; Synthesis, 1.21 mm, SD 3.39) between systems. This trial was judged to have a low risk of bias. It fulfilled 3 major methodologic criteria and all minor methodologic criteria. The author was contacted for further information.

Heterogeneity, sensitivity analyses, and publication bias

No meta-analysis, combining more than 1 study, was undertaken; thus, this did not apply.

Secondary outcomes

Other outcomes such as patient’s perception of RR, tooth mobility, tooth loss, or quality-of-life data were not recorded in any studies.

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses