Direct laryngoscopy remains the technique of choice for placing an endotracheal tube (ETT). However, alternative techniques are needed for the difficult airway or unsuccessful intubation. Retrograde intubation may be used in adult or pediatric patients, whether awake, sedated, or obtunded. Contraindications include nonpalpable neck landmarks, pretracheal mass, severe flexion deformities of the neck, tracheal stenosis, coagulopathies, and infections. Submental intubation allows simultaneous access to the dental occlusion and nasal pyramid without the morbidity associated with tracheostomy. Contraindications include patients who require long periods of assisted ventilation and a severe traumatic wound on the floor of mouth. Complications include localized infection and sepsis, poor wound healing or scarring, and postoperative salivary fistula.

Retrograde intubation

Retrograde intubation was first described in 1963 by Waters, who used this technique for intubation of a patient with cancrum oris. Direct laryngoscopy remains the technique of choice to place an endotracheal tube (ETT). However, alternative techniques may be needed when the airway is found to be difficult or intubation unsuccessful. The retrograde intubation technique is an option for managing the difficult airway and is discussed in the American Society of Anesthesiology difficult airway algorithm. It may be especially useful when a fiberoptic system is not readily available.

Retrograde intubation is one of many techniques that can be used in those cases where oral or nasal tracheal intubation may be extremely difficult or impossible because of factors already discussed in this atlas. Retrograde intubation is a reliable and easily learned technique that offers an alternative to more invasive surgical solutions for securing the airway.

The advantage of retrograde intubation is that it can be used in adult or pediatric patients who are whether awake, sedated, or obtunded. This technique is indicated in those patients who cannot be intubated in a traditional manner but whose condition is not extreme enough to warrant a surgical airway. This technique may also be used to secure a nasoendotracheal tube, by passing the guidewire through the nose instead of the mouth. Contraindications to retrograde intubation include nonpalpable neck landmarks, pretracheal mass, severe flexion deformities of the neck, tracheal stenosis, coagulopathies, and infections.

Technique

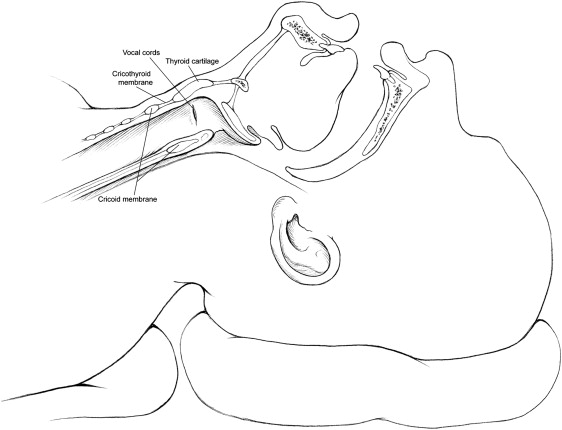

Patients should be supine in the operating theater and be receiving supplemental oxygen through a nasal canula or face mask. The thyroid and cricothyroid cartilages are palpated and, if time permits, marked with a surgical marking pen ( Fig. 1 ). Palpation of the cricothyroid membrane is then performed. Local anesthesia may be administered in the skin overlying the cricothyroid membrane. Airway reflexes can be blunted with 4% lidocaine directly into the trachea, by aerosolization or topical application. After the skin has been prepared, an 18-gauge introducer needle is passed through the skin and cricothyroid membrane and pointed in a cephalad direction at approximately a 45° angle ( Fig. 2 ). Correct placement in the trachea is confirmed by attaching the needle to a 10-mL syringe containing approximately 5 mL of normal saline. Once the needle has been passed through the skin and entered the trachea, the plunger on the syringe is aspirated. If the needle is in the trachea, air bubbles will be seen in the syringe (see Fig. 2 ). The syringe is removed, maintaining the needle in the proper position. A 50-cm flexible J-tipped guidewire is then passed through the needle and directed superiorly so that the distal end of the wire can be retrieved from the mouth. Once the guidewire is visible in the mouth, hemostats are used to grasp the tip of the wire and advance it out of the mouth ( Fig. 3 ). Once the guidewire is properly secured, the needle is withdrawn off the wire. An appropriate length of wire must be brought through the mouth so that an endotracheal tube can be passed over the wire while still controlling the end of wire. At this point, the wire should be relatively straight and taut. The endotracheal tube is advanced slowly over the wire and through the mouth ( Fig. 4 ). The endotracheal tube is gradually advanced to the level of the cricothyroid. The wire may be relaxed to allow the tube to enter the trachea. Attempts to advance the endotracheal tube may result in tenting of the skin at the location of the guidewire ( Fig. 5 ), whereupon the skin end of the wire is withdrawn from the cricothyroid membrane and endotracheal tube from the mouth. The endotracheal tube can now be advanced in the normal fashion, and confirmation of the tube’s position is performed in the usual manner.