A 40-year-old black woman, with pretorqued, preangulated appliances on the maxillary teeth, transferred with chief concerns of missing teeth and her orthodontic progress. She had bialveolar protrusion and edentulous areas in both the maxilla and the mandible. After records were made and her desires assessed, she was retreated with the extraction of 3 premolars. Her protrusion was reduced and all edentulous spaces were closed. The facial change was evident due to the reduction of the protrusion.

Highlights

- •

Treating a transfer patient requires tact.

- •

The transferring and the accepting orthodontists should focus on the facts and the patient’s well-being.

- •

Select the treatment option that best meets the hierarchy of care.

- •

When major esthetic changes are contemplated, patient preferences are paramount.

Transfer patients sometimes pose a dilemma. Does the accepting orthodontist follow the original treatment plan? Or, after reviewing the transfer records and having a frank discussion with the patient, does he or she change the treatment plan? If this is the scenario, it must be made absolutely clear to the patient that the previous treatment plan was not “wrong,” but rather that it was a plan that was not working or did not work.

This black woman (age, 40 years 1 month) had been wearing appliances for 13 months. She had bialveolar protrusion with flaring of both the maxillary and the mandibular anterior teeth, protrusion of the lips, facial strain, and a convex facial profile. She desired a facial change—reduction of the protrusion.

The American black facial pattern is diversified, but one common facial type is bialveolar protrusion, which is characterized by flaring of the maxillary and mandibular anterior teeth, protrusion of the lips, and a convex facial profile. A common treatment approach for this type of malocclusion is to extract teeth in the midarch and retract the anterior teeth. This approach reduces the fullness of the lips and decreases the facial convexity. In some patients, an orthognathic procedure can be indicated if the skeletal discrepancy warrants it.

The question often raised is how much convexity should be reduced. Peck and Peck studied the concept of beauty as related to the white profile. They found that the public prefers a slightly more protrusive facial profile than customary orthodontic standards would dictate. They stressed the importance of the public’s opinion and stated that the “ultimate source of our esthetic values should be the people, not just ourselves (orthodontists).”

Foster studied profile preferences with silhouettes. The groups included black, white, and Chinese subjects who were art students, general dentists, and orthodontists. The results indicated that the groups shared a common esthetic standard for the posture of the lips that was within 1 to 2 mm. All groups were consistent in assigning fuller lips for younger ages. For adults, a straight profile was preferred.

Thomas surveyed black and white orthodontists using soft-tissue profile tracings of photographs that represented 10 common soft-tissue profiles. He found that both black and white orthodontists preferred a straighter profile with good facial balance and mild convexity.

Farrow et al, using photographs that were altered to depict different levels of bialveolar protrusion, found that black Americans prefer a straighter profile, but not necessarily a “white” profile.

Sushner studied 100 lateral photographs of black people who were deemed attractive. Their profiles were compared with the standards of Steiner, Holdaway, and Ricketts. Sushner concluded that black profiles were significantly more protrusive than white profiles, and that evaluations of black profiles should be made without imposition of white standards. He established black norms using the esthetic lines of Steiner, Holdaway, and Ricketts.

History and etiology

The patient had an unremarkable medical history. Her dental history showed the loss of the maxillary left second premolar and the mandibular second molars. She had a Class I dentition with bialveolar protrusion and was wearing a preangulated, pretorqued appliance on her maxillary teeth, and only the mandibular first molars were banded in the mandibular arch. Prior orthodontic records were requested, but only panoramic and cephalometric radiographs were received. The patient’s chief concerns were her “missing teeth and her orthodontic progress.” The primary etiology was heredity.

Diagnosis

The facial photographs and intraoral photographs ( Fig 1 ) demonstrate the convex facial profile. The patient could not close her lips without mentalis strain.

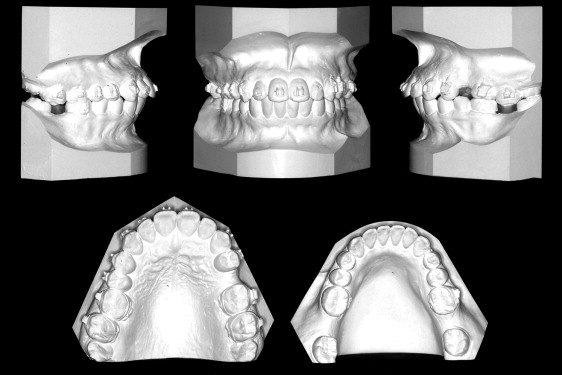

The dental casts ( Fig 2 ) showed an Angle Class I occlusion. The maxillary left second premolar and the mandibular second molars were missing. All third molars were present. There were edentulous areas in the maxillary left second premolar and the mandibular second molar areas. The maxillary left second molar was extruded into the mandibular left second molar’s edentulous space.

The panoramic radiograph ( Fig 3 ) shows that all teeth were present except the maxillary left second premolar and the mandibular second molars. The mandibular third molars were mesioaxially inclined into the edentuluous space that was created by the missing mandibular second molars. There was bone loss on the maxillary anterior teeth.

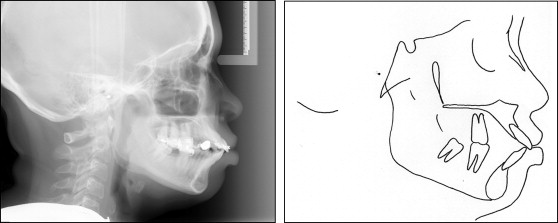

The cephalogram and its tracing ( Fig 4 ) illustrate an ANB angle of 4°. The SNA angle of 85° confirmed the maxillary procumbancy. The FMA was 20°. The facial height index was 0.75. The IMPA angle of 115° and an interincisal angle of 96° reflect proclination of the mandibular and maxillary incisors. The Z-angle of 45° confirmed a protruded soft-tissue overlay ; however, the Wits measurement of 0 mm reflected no alveolar imbalance. McNamara’s nasion Frankfort perpendicular suggested bialveolar protrusion.

Diagnosis

The facial photographs and intraoral photographs ( Fig 1 ) demonstrate the convex facial profile. The patient could not close her lips without mentalis strain.

The dental casts ( Fig 2 ) showed an Angle Class I occlusion. The maxillary left second premolar and the mandibular second molars were missing. All third molars were present. There were edentulous areas in the maxillary left second premolar and the mandibular second molar areas. The maxillary left second molar was extruded into the mandibular left second molar’s edentulous space.

The panoramic radiograph ( Fig 3 ) shows that all teeth were present except the maxillary left second premolar and the mandibular second molars. The mandibular third molars were mesioaxially inclined into the edentuluous space that was created by the missing mandibular second molars. There was bone loss on the maxillary anterior teeth.

The cephalogram and its tracing ( Fig 4 ) illustrate an ANB angle of 4°. The SNA angle of 85° confirmed the maxillary procumbancy. The FMA was 20°. The facial height index was 0.75. The IMPA angle of 115° and an interincisal angle of 96° reflect proclination of the mandibular and maxillary incisors. The Z-angle of 45° confirmed a protruded soft-tissue overlay ; however, the Wits measurement of 0 mm reflected no alveolar imbalance. McNamara’s nasion Frankfort perpendicular suggested bialveolar protrusion.

Treatment objectives

The treatment objectives were to (1) improve the profile line to nose relationship and the Z-angle, (2) obtain normal canine and incisal guidance, (3) close the edentulous spaces in both dental arches, (4) reduce the excessive procumbancy of both dental arches, and (5) intrude the maxillary left second molar.

Treatment alternatives

The patient was shown profile changes that were possible on other adult patients with a similar malocclusion. The pros and cons of absolute anchorage (mini bone plates) vs conventional anchorage (extraoral force) were explained. The patient was given a choice between the following options.

- 1.

Extract the maxillary right first premolar and the mandibular first premolars to reduce her facial fullness and improve her profile line to nose relationship. Close the mandibular molar space. Place mini bone plates in all posterior quadrants to provide absolute anchorage to correct the dental protrusion and close the edentulous molar spaces. This plan would eliminate prosthetic dental implants and produce a facial change.

- 2.

Continue the original treatment plan and place dental implants to restore the edentulous spaces. Use temporary skeletal anchorage devices to intrude the maxillary left second molar. With this option, a facial change was not possible.

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses