-

Chapter Outline

Learning Objectives

After reading this chapter, the student should be able to:

- 1.

Recognize situations that might require nonsurgical root canal retreatment.

- 2.

Identify the treatment options available for teeth with endodontic problems.

- 3.

State the indications and contraindications for root canal retreatment.

- 4.

Describe the risks and benefits of retreatment.

- 5.

Describe techniques and materials used in endodontic retreatment.

- 6.

Discuss restorative options and follow-up care.

- 7.

Discuss the prognosis and outcomes for nonsurgical endodontic retreatment.

Learning Objectives

After reading this chapter, the student should be able to:

- 1.

Recognize situations that might require nonsurgical root canal retreatment.

- 2.

Identify the treatment options available for teeth with endodontic problems.

- 3.

State the indications and contraindications for root canal retreatment.

- 4.

Describe the risks and benefits of retreatment.

- 5.

Describe techniques and materials used in endodontic retreatment.

- 6.

Discuss restorative options and follow-up care.

- 7.

Discuss the prognosis and outcomes for nonsurgical endodontic retreatment.

Treatment Options

After initial root canal therapy, unsatisfactory short-term and long-term outcomes are primarily due to three causes: (1) nonhealing, (2) recurrence of endodontic disease, and (3) development of new disease and complications.

With nonhealing, a tooth with endodontic disease continues to have a problem after initial endodontic therapy. This may result from many factors, which are described in more detail throughout this chapter.

Recurrence of endodontic disease is found when healing occurs from the initial treatment, but bacteria subsequently regain entrance to the root canal system and reinfect the tooth. The tooth initially is comfortable, with no signs of disease, but later the patient may complain of symptoms. Both radiographic and clinical evidence of new endodontic concerns also may be seen.

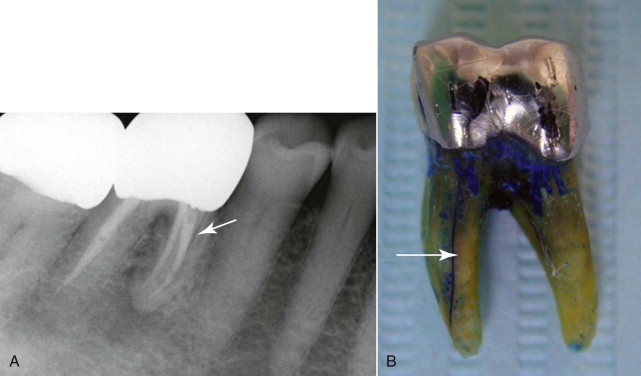

With the third main cause, namely development of a new problem after initial successful treatment of a tooth, complications arise that are not directly related to the root canal treatment. An example of such a situation is an endodontically treated tooth that develops a vertical root fracture (VRF). These fractures typically occur sometime after initial root canal treatment and may be recognized as lateral lesions instead of the usual apical lesions associated with root canal infections ( Fig. 20.2 ). A VRF can occasionally be traced using a periodontal probe if the fracture extends coronally to the crestal bone. Although single-rooted teeth that develop VRFs usually need to be extracted, the failure in this case is not directly related to the root canal treatment. A similar situation is the endodontically treated tooth that may need to be extracted for periodontal reasons; the reason for extraction is unrelated to the endodontic procedure. Other endodontic surgical procedures may be used to salvage portions of multirooted teeth that are not affected by the VRF.

When initial root canal treatment fails to promote healing, the treatment options to save the tooth include nonsurgical retreatment with or without apical surgery, apical surgery, intentional replantation, and extraction. If the tooth is restorable, nonsurgical retreatment is usually the preferred treatment strategy. This option may allow an opportunity to better disinfect the root canal system or to address areas of reinfection due to bacterial leakage associated with poor coronal restorations. Because orthograde endodontic retreatment may not allow access to all areas of canal infection, or if extraradicular infection is present, apical surgery may be a required part of the retreatment.

Surgical treatment may be considered a first choice in the presence of canal obstructions or extensive fixed prosthetic appliances or when removal of extruded filling materials is indicated. However, surgical endodontic treatment may not eliminate surviving microorganisms in inaccessible areas of the root canal system. Even when surgical treatment is required, nonsurgical retreatment prior to surgical treatment has been shown to improve healing and to help achieve a successful outcome.

Intentional replantation of teeth is a treatment option that has a long history in dentistry. When properly planned and executed, intentional replantation has been shown to be quite successful in providing patients with additional years of service from their teeth. This procedure can be considered for teeth that are not badly broken down but in which the initial root canal treatment has not allowed access to all of the root canal system, and apical surgery is complicated by anatomic difficulties. It also allows an opportunity to examine the roots of teeth for possible vertical fracture lines.

Retreatment procedures are usually more difficult to perform than those used in the initial treatment. They frequently require advanced instrumentation, magnification systems, and special training. Endodontists have extensive training and practice in evaluating and managing teeth with apparent lack of healing after initial root canal therapy and teeth developing new lesions. Much of this chapter discusses procedures performed by specialists. This discussion is intended to provide information on the techniques used by someone trained in such procedures. The emphasis in this chapter is on recognizing nonhealing and the recurrence of endodontic disease and on developing an understanding of what can be achieved.

Indications for Nonsurgical Endodontic Retreatment

The following describes a typical situation of a nonhealing initial root canal treatment based on a diagnosis of pulp necrosis and symptomatic apical periodontitis. The patient complains that the symptoms have not improved since the time of initial treatment and that the discomfort has in fact increased. Chewing and biting are painful, but the pain may also occur spontaneously. Radiographic examination reveals an emerging apical radiolucency not present at the time of initial treatment.

Clinical examination of teeth with nonhealing endodontic disease may reveal palpation and percussion sensitivity, localized swelling, recurrent caries, leaky provisional restorations, and substandard or missing coronal restorations. Radiographic evaluation may show the presence of untreated canals, poor canal obturation with voids, separated instruments, recurrent caries not located during the clinical examination, or defective restorations with open margins. All such findings can contribute to nonhealing associated with the previous treatment. Any combination of clinical symptoms and radiographic and clinical findings may indicate nonhealing. Nonhealing can also be present without any contribution from the aforementioned conditions.

Retreatment is considered the primary treatment option when the tooth is found to be periodontally stable; there is adequate remaining tooth structure with no detectable vertical fractures; and access to the root canal system is feasible. After disassembly of any defective restorations and post and core materials and the removal of all caries, tooth restorability must be determined. This initial assessment includes periodontal probing, mobility tests, and periapical and bitewing radiographs to determine the crown to root ratio, presence of supporting bone, health of the soft tissue, and need for crown lengthening procedures.

It is important for the chairside staff to be familiar with retreatment procedures so that endodontic care can be delivered in a professional and effective manner. The office must be equipped with the necessary illumination and magnification systems, ultrasonic units and appropriate tips, rotary handpieces, endodontic files, solvents, dental dams, various post extraction kits, and irrigation systems. The clinician must have high levels of skill, experience, and training to execute retreatment in an effective manner. Because these cases are commonly complex and challenging, the best interest of the patient should be considered when the decision is made to offer treatment or to recommend referral to a specialist.

Contraindications to Nonsurgical Endodontic Retreatment

A major factor when nonsurgical retreatment is considered is the restorability of the tooth after the necessary removal of preexisting restorative materials. Additional tooth structure may be lost during caries removal and removal of post and core materials. Lack of adequate tooth structure to support a postendodontic restoration is a contraindication to nonsurgical retreatment. The restorability decision often requires extensive disassembly of existing restorations and evaluation of the remaining root canal system. Other contraindications include the presence of extensive periodontal involvement of the tooth that weakens the tooth support and/or the presence of problematic coronal or radicular fractures.

Indications for Surgical Retreatment

Further contraindications to nonsurgical root canal retreatment include intracanal complications. For instance, access to the canals may not be possible due to the presence of obstructions. These obstructions include large, tight-fitting, prefabricated or cast posts and cores, root canal calcifications, and other obstructions that may prevent access. In such situations, surgical retreatment may offer the best available option. Examples of possible root canal obstructions are the presence of separated instruments that cannot be bypassed or retrieved, filling materials that cannot be adequately removed, and teeth that after orthograde retreatment exhibit nonresponding periapical lesions. Teeth with iatrogenic mishaps that cannot be adequately addressed, such as nonnegotiable ledges, transportation of the canal or apex, or perforations that cannot be repaired internally, also may be candidates for a surgical approach.

Teeth with external root resorption associated with a history of trauma and infected pulp tissue that were inadequately treated previously may be retreated in an orthograde approach. Surgical repair of resorptive areas on the external aspects of the roots is usually not indicated.

Extraction usually is indicated for teeth diagnosed with a VRF. An exception may be a multirooted maxillary molar that develops a VRF in one of the roots. Because replacement with a dental implant may be difficult due to the type or absence of alveolar bone, surgical amputation of the root with a VRF can provide a tooth that may serve satisfactorily for many years. Each clinical situation is unique to the patient with the endodontic problem, and treatment options must be evaluated by carefully taking into account all aspects of the patient’s situation.

Risks and Benefits of Retreatment

The patient must be informed of the risks, benefits, alternatives, and consequences of the various treatment modalities prior to initiation of treatment. The discussion with the patient must include the importance of good oral hygiene and regular evaluation of the teeth. Because retreatment is often time-consuming, the cost of treatment must be explained.

Nonsurgical root canal retreatment procedures have many potential risks. These include fracture of a porcelain crown during the access procedure, fracture of the root during post removal procedures, iatrogenic perforations during core and obturation material removal, and dislodgement of the crown that may necessitate replacement. In addition, retreatment procedures may cause extensive removal of tooth structure that may further weaken the tooth, create ledges, or cause canal transportation. The separation of an instrument may impede the ability to completely remove obturation materials also. All of these complications may affect the retreatment outcome and potentially lead to necessary extraction. The benefits of retreatment include the preservation and retention of the patient’s natural tooth structure and the avoidance of more extensive clinical treatment.

Endodontic Retreatment Procedures

Removal of Existing Restorations

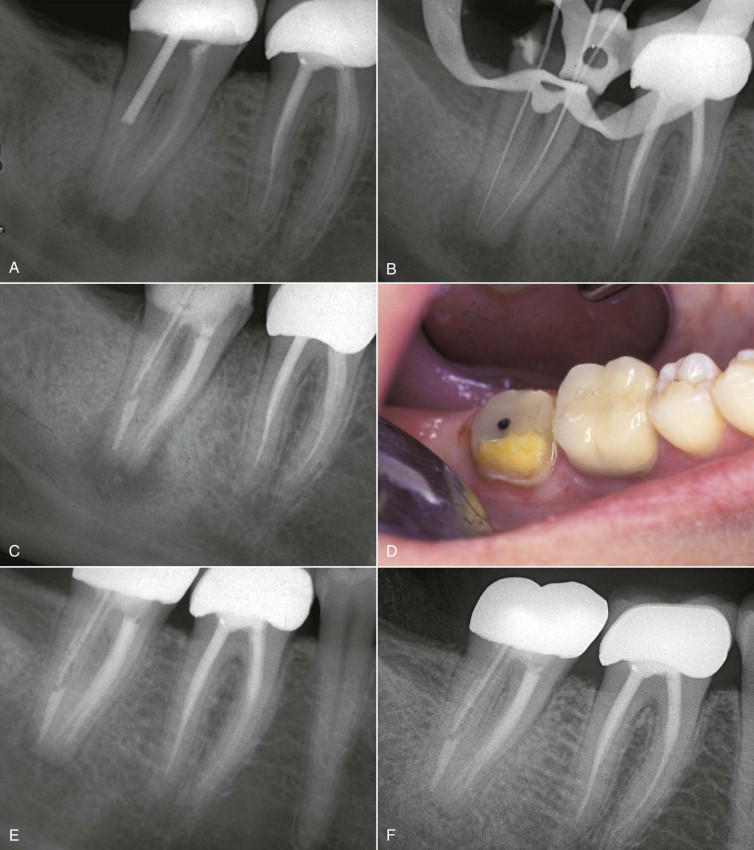

Nonsurgical endodontic retreatment procedures are often more feasible if the coronal restorations are completely removed. This allows better visualization and access for post and core removal, caries excavation, assessment and management of coronal microleakage, and removal of obturation materials from the canals ( Fig. 20.3 ).

After disassembly of the coronal restoration, a clearer assessment of potential coronal microleakage can be made. If microleakage is evident, the entire remaining tooth structure can be inspected, including the canals and the pulpal floor. Disassembly also allows inspection for possible recurrent caries and fractures and evaluation of the tooth’s restorability. When posterior teeth have been restored with either composite resin or amalgam, the entire restoration should be removed. The remaining coronal structure can then be assessed for a new restoration that can provide adequate cuspal coverage and protection.

When a tooth presents with a full coverage restoration and exhibits recurrent caries, open margins, or loss of marginal integrity, complete removal of the restoration is also indicated. In many cases this is necessary for post and core disassembly. Anterior teeth with cosmetic crowns that exhibit acceptable marginal integrity without the presence of recurrent caries may be retreated through a lingual access opening, but the risk of crown fracture is still present. If there is a large metallic or nonmetallic post, crown removal most likely will be required to complete the treatment. Patients must be informed of the possibility of porcelain fracture, crown dislodgement, or root fracture, which may occur through any phase of retreatment. If the structural integrity of the prosthetic crown is compromised, the patient will most likely require a new restoration. If retreatment can be completed with the original full coverage restoration remaining intact, the access cavity can be filled with a permanent restorative material.

Removal of Canal Obstructions

Canal obstructions occasionally prevent successful negotiation of the root canal system during nonsurgical root canal treatment. Nonhealing is likely if these obstructions are not bypassed or removed. Surgical treatment may need to be included to manage these treatment challenges.

The four categories of canal obstructions are (1) posts and cores, (2) calcifications of the root canal system, (3) iatrogenic ledges and dentinal debris in the root canal system, and (4) separated instruments, silver points or metallic debris, and some paste materials. These are typically complex treatment situations that frequently require extensive training and experience to manage. For the benefit of the patient, referral to a specialist should be considered and offered. The following are general descriptions of the procedures used.

Post and Core Removal

Successful removal of posts and cores during retreatment depends on several factors that influence the outcome. These include the operator’s level of skill, experience, and training and the availability of magnification, illumination, and ultrasonic systems. Other outcome considerations include the type of core material (cast versus resin or amalgam); the length and diameter of the preformed or cast post, post location, and post material (metallic or nonmetallic); and type of cement or bonding system used to secure the post and core system. Any number of methods used to remove posts can compromise the existing tooth structure. Some posts may be difficult or impossible to remove if they are long, well fitted, or cemented with bonding systems or resin cements ( Fig. 20.4 ). Nonmetallic posts are very difficult to remove, particularly when they are tooth colored or made of zirconium ( Fig. 20.5 ). Removal of long or large-diameter posts may be contraindicated if the existing root structure is thin or if perforation or a root fracture is likely to occur during the procedure.

In preparation for post removal, the coronal core material must be carefully sectioned and removed incrementally to preserve the portion of the post that extrudes coronally from the root canal. Removal of the core material may require diamond, transmetal, and carbide burs or specifically designed ultrasonic tips.

This procedure is best performed using illumination and magnification to help preserve adjacent tooth structure during the procedure. After core removal, any visible cement surrounding the post can be circumferentially removed using fine ultrasonic tips or a flame-tipped diamond bur.

After the surrounding cement has been removed, the post can be loosened using specially designed ultrasonic tips at medium to high energy settings. This procedure must be executed with caution because it rapidly generates extremely high temperatures if performed without water coolant. Therefore, ultrasonic energy should be delivered in different locations around the exposed portion of the post at intervals lasting no longer than 15 seconds. Ultrasonic tips used without water coolant and placed in contact with posts generate temperature increases of 10°C within 1 minute on the external root surface. If this threshold temperature is reached, it can cause heat-induced bone necrosis, with possible loss of the tooth and supporting bone.

The time required to loosen posts depends on several factors, including the type of post (cast or preformed), the length and width of the post, and the luting agent used. Posts cemented with zinc phosphate cement are generally easier to remove than those cemented with resin cements. Posts cemented with resin cements are difficult or even impossible to remove.

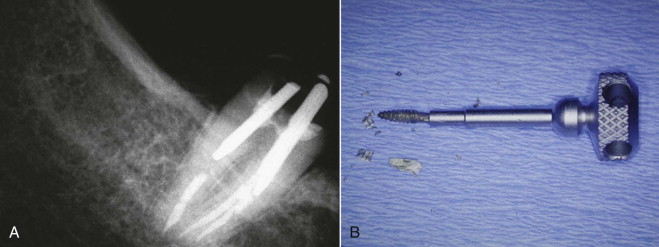

Once the post has been loosened, various-sized hemostats or small-tipped forceps or pliers can be used to grasp and remove it. In many cases the post can be dislodged using only ultrasonic energy. Screw posts can usually be removed with hemostats by turning them counterclockwise. When these methods are unsuccessful, post removal can be accomplished by using specially designed devices. There is a greater risk of fracturing the tooth or removing excessive tooth structure using these instruments if the post is not first loosened with ultrasonics. There does not seem to be any difference in the risk of root fracture between ultrasonic and post removal devices. After post removal, any excess cement can be removed using a combination of solvents, rotary or hand instruments, or ultrasonic tips.

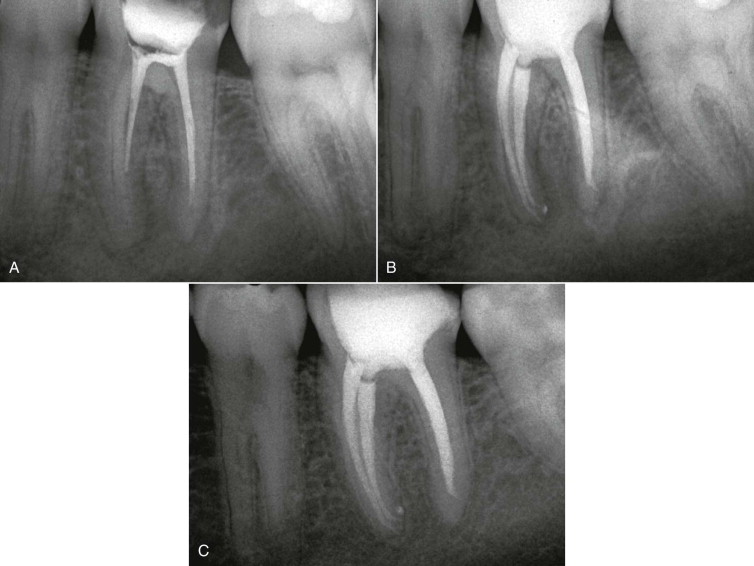

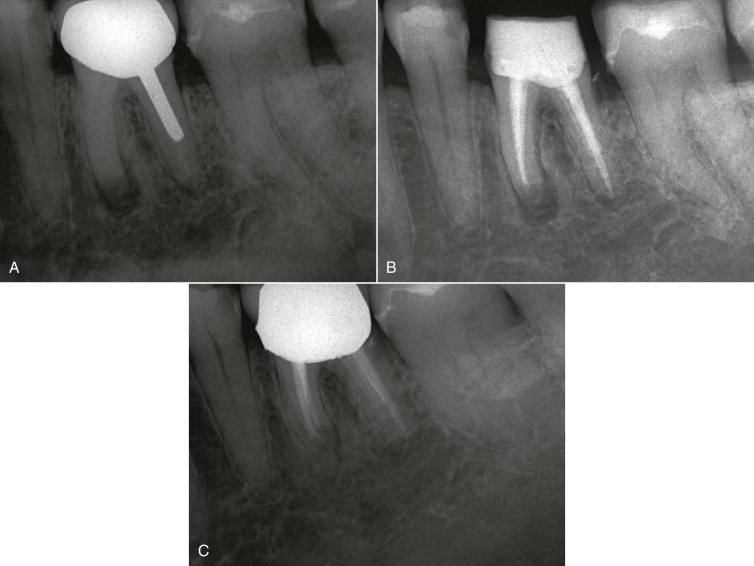

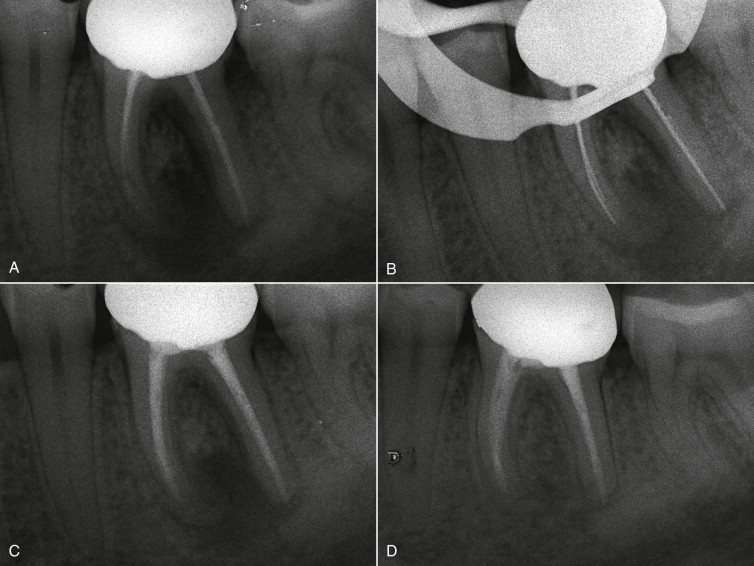

The following is an example of post removal using a specially designed device ( Fig. 20.6 ). The coronal portion of the post is first reduced in size using a high-speed transmetal or diamond bur. After the reduction, a matching-size trepan bur is used to trough the post circumferentially, avoiding excess removal of tooth structure. The coronal portion of the post is tapped with the matching-size extractor to firmly grasp the post, and the extractor is engaged with the specially designed pliers ( Fig. 20.7 ). The remaining tooth structure is cushioned with rubber washers that allow the tooth to act as a fulcrum when the pliers are engaged. The technique is effective and has been shown to be relatively safe. After the post and cement have been successfully removed, cleaning, shaping, and obturation of the canal system can proceed with the appropriate instruments and filling materials ( Figs. 20.8 and 20.9 ).

Removal of Calcifications

Root canal calcifications may be noted radiographically, but internal visualization benefits from magnification and illumination using the dental operating microscope (DOM). Other obstructions must be removed before attempts are made to explore the calcified area. Once the area has been visualized, a combination of chelating agents, stiff hand files (e.g., C and C+ files), and ultrasonic tips or Mueller-type burs may be used to remove the calcified tissue to locate the root canal apical to the calcification. Removal of the calcified barrier is restricted to the straight portion of the root canal when ultrasonic instrumentation or Mueller burs are used. If the canal is located with the aid of microexplorers and the DOM, a small bend can be placed on stiff, small-diameter hand files, and the curved portion of the canal can be carefully negotiated using various chelating agents and lubricants. The canal is then enlarged, using the crown-down technique, with a combination of hand files, Gates-Glidden drills, or a high-taper nickel-titanium rotary file system. If the canal cannot be negotiated due to extensive calcification or any other obstruction and an apical lesion is associated with the root, surgical intervention must be considered.

Management of Ledges

Ledges are generated during canal preparation if canal curvature is not maintained. These canal problems typically occur when stainless steel files are not properly precurved to match the canal curvature. Stainless steel files have elastic memory and tend to straighten canals, thus creating ledges in the canal walls. This can lead to perforations if the situation is not recognized in a timely manner. Nickel-titanium rotary instruments reduce ledge formation because the files tend to stay centered during preparation of the canal curvature.

If a ledge is encountered during the retreatment procedure, all obstructions and obturation materials must be removed and the ledge visualized after the canal has been opened up using the crown-down technique. A hand file with a sharp bend at the tip is applied with a watch-winding motion in an attempt to bypass the ledge apically. If the negotiation around the ledge is successful, the canal can be circumferentially filed until the irregularity is removed or smoothed enough to allow predictable instrumentation and obturation. Hedstrom files are an excellent option for ledges that may be more difficult to remove, but they should be used with extreme caution. After successful bypass and removal of the ledge, the apical portion of the canal can be cleaned and prepared using any of the instrumentation systems. It is worth noting that unsuccessful attempts at bypassing ledges do not always result in nonhealing ( Fig. 20.10 ).

Instrument Fragment Removal

Successful removal of separated instrument fragments in the root canal system is influenced by various factors. These include the operator’s experience and level of skill; the size, length, and location of the separated fragment; and the retrieval technique selected. Smaller instruments that are easily accessible in the coronal portion of the root canal system can be ground away or bypassed using burs or ultrasonic instruments. Fragments deeper in the canal system may require the use of devices or kits designed specifically for this purpose ( Fig. 20.11 ).

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses