This case report presents the successful replacement of 1 first molar and 3 second molars by the mesial inclination of 4 impacted third molars. A woman, 23 years 6 months old, had a chief complaint of crowding of her anterior teeth and linguoclination of a second molar on the left side. The panoramic radiographic images showed that the maxillary and mandibular third molars on both sides were impacted. Root resorption on the distal surfaces of the maxillary second molars was suspected. The patient was given a diagnosis of Angle Class II Division 1 malocclusion with severe crowding of the anterior teeth and 4 impacted third molars. After we extracted the treated maxillary second premolars and the second molars on both sides, the treated mandibular second premolar and the second molar on the left side, and the root canal-filled mandibular first molar on the right side, the 4 impacted third molars were uprighted and formed part of the posterior functional occlusion. The total active treatment period was 39 months. The maxillary and mandibular third molars on both sides successfully replaced the first and second molars. The replacement of a damaged molar by an impacted third molar is a useful treatment option for using sound teeth.

Highlights

- •

The replacement of a damaged molar by an impacted third molar is a useful treatment option for utilizing sound teeth.

- •

Not only the mesial tilting of an impacted mandibular third molar but also the vertical position may be associated with the subsequent eruption after first or second molar extraction.

- •

In choice of orthodontic extraction, skeletal anchorage such as miniscrews is effective to keep permanent teeth of good condition.

- •

An orthodontic treatment of the posterior scissors bite may improve the masticatory function.

Retained asymptomatic third molars pose a risk for second molar incident pathology in middle-aged and older adults. Prophylactic extraction of unerupted asymptomatic third molars is frequently performed to prevent the risk of adjacent second molar pathology (eg, caries, periodontitis, resorption of adjacent tooth roots). However, it has been reported that a maxillary or a mandibular permanent third molar was uprighted and acceptably replaced the second molar after extraction in orthodontic treatment. Orthodontic treatment with extraction of the permanent first molars similarly increases the eruption spaces of the third molars and decreases their impaction. The alignment of the permanent third molars after the extraction of the permanent first or second molars is a useful option for adult patients when the permanent first or second molars are severely damaged.

An important concern of permanent molar extraction is the prognosis of the presence and eruption of the third molar. Excessive tilting of the third molars, advanced development of their roots, and older patient age are important for the successful eruption of the third molars. Some authors have recommended not extracting the second molar if the third molar has a buccolingual orientation or if the angle with the first molar is greater than 30°. Unsuccessfully erupted third molars reportedly occur in older patients with higher Nolla developmental stages. Several reports have shown that maxillary and mandibular third molars replace second molars quite successfully, although these were in growing patients (ages, 13.2-16.6 years). Because the permanent molars erupt at an early age and are prone to dental decay, conservative treatment has frequently been performed before orthodontic treatment begins in adult patients. Therefore, in adults, it is necessary to carefully consider the prognosis of extracting a damaged permanent premolar or molar in addition to extraction for orthodontic reasons.

In this case report, we present the successful replacement of 1 first molar and 3 damaged second molars by 4 mesially tilted impacted third molars, and the extraction of a restored second premolar using miniscrew anchorage in an adult with severe crowding of the anterior teeth and 4 impacted third molars.

Diagnosis and etiology

A woman, who was 23 years 6 months old, came to the orthodontic department of Kagoshima University Hospital in Kagoshima, Japan. Her chief complaints were crowding of the maxillary and mandibular anterior teeth and linguoclination of the second molar on the left side. She also felt that it was difficult to masticate on the left side because of a scissors-bite malocclusion of the second molars. She had a convex profile, and the maxilla and the lower lip were slightly protruded (E-line: upper lip, 3.5 mm; lower lip, 9.5 mm) ( Table ). She also had circumoral musculature strain on lip closure. No facial asymmetry was evident in the frontal view ( Fig 1 ).

| Measurement | Pretreatment (23 y 6 mo) | Posttreatment (27 y 1 mo) | Postretention (28 y 6 mo) | Japanese norm for women (Mean ± SD) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SNA (°) | 80.5 | 80.5 | 80.5 | 80.8 ± 3.6 |

| SNB (°) | 75.0 | 74.5 | 74.5 | 77.9 ± 4.5 |

| ANB (°) | 5.5 | 6.0 | 6.0 | 2.8 ± 2.4 |

| Facial angle (°) | 82.5 | 82.0 | 82.0 | 84.2 ± 4.4 |

| Angle of convexity (°) | 13.0 | 13.5 | 13.5 | 7.6 ± 5.0 |

| Y-axis (°) | 68.0 | 68.5 | 68.5 | 66.1 ± 3.6 |

| Mandibular plane angle (°) | 34.5 | 35.0 | 35.0 | 30.5 ± 3.6 |

| Occlusal plane to SN (°) | 16.5 | 16.5 | 19.0 | 16.9 ± 4.4 |

| U1 to SN (°) | 111.0 | 93.0 | 94.0 | 105.9 ± 8.8 |

| U1 to FH (°) | 119.5 | 101.0 | 102.0 | 112.3 ± 8.3 |

| L1 to MP (°) | 102.0 | 91.5 | 93.0 | 93.4 ± 6.8 |

| FMIA (°) | 43.5 | 53.5 | 52.0 | 56.0 ± 8.1 |

| Interincisal angle (°) | 104.0 | 132.5 | 130.0 | 123.6 ± 10.6 |

| U1 to A-Pog (mm) | 14.5 | 7.5 | 8.0 | 6.2 ± 1.5 |

| L1 to A-Pog (mm) | 10.0 | 4.5 | 5.0 | 3.0 ± 1.5 |

| E-line: upper lip (mm) | 3.5 | 1.0 | 1.0 | −3.0 ± 1.0 |

| E-line: lower lip (mm) | 9.5 | 4.0 | 5.0 | 1.1 ± 1.5 |

| Overjet (mm) | 4.5 | 3.0 | 3.0 | 3.1 ± 1.1 |

| Overbite (mm) | 1.0 | 2.0 | 2.5 | 3.3 ± 1.9 |

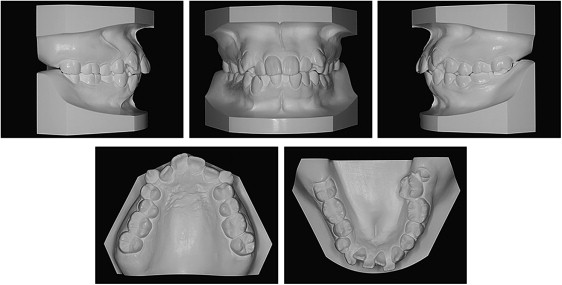

On intraoral examination, the canine and molar relationships were Class I on both sides, but she had a scissors-bite of the second molar on the left side. Overjet was 4.5 mm, and overbite was 1.0 mm. The dental midline was coincident with the facial midline. On dental cast analysis, the arch length discrepancies were −12.5 mm in the maxilla and −8.2 mm in the mandible ( Fig 2 ).

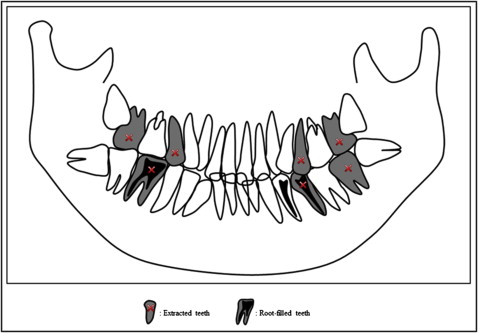

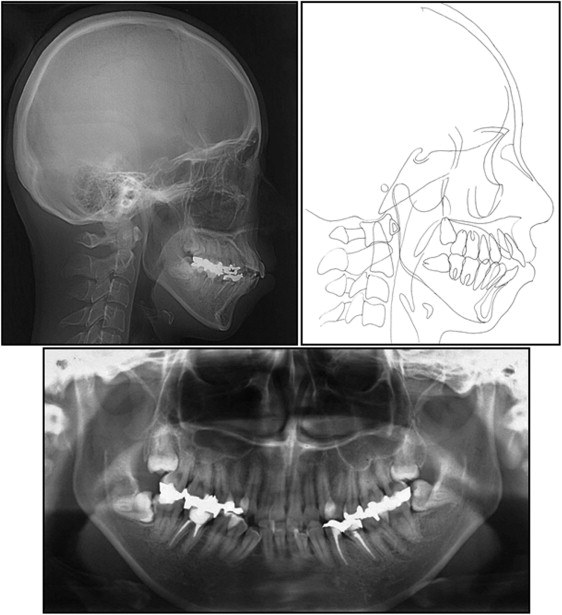

Panoramic radiographic findings showed that the maxillary third molars on both sides were impacted, and root resorption on the distal surface of maxillary second molars was suspected ( Fig 3 ). There was excessive mesial tipping of the impacted mandibular third molar on both sides. The mandibular first molar on the right side and the mandibular first and second premolars were root canal-filled and largely restored.

In comparison with Japanese norms, the cephalometric analysis showed a skeletal Class I jaw base relationship (ANB angle, 5.5°) with a high mandibular plane angle (MP-FH, 34.5°) ( Fig 3 , Table ). The maxillary and mandibular incisors were labially inclined (U1-FH angle, 119.5°; L1-MP, 102.0°).

An optoelectric jaw-tracking system (Gnatho-Hexagraph II; GC International, Tokyo, Japan) was used to record jaw movement with 6 degrees of freedom. During the maximum open-close exercise, no asymmetric or limited movements of the bilateral condyles and no obvious lateral shift of the mandibular incisor were observed. In the unilateral masticatory test with chewing gum, the maximum closing velocity on the right side (the nonscissors-bite side) was faster than the velocity on the left side (the scissors-bite side), and there was a more stable chewing pattern on the right side than on the left side. She realized her tendency to chew primarily on the nonscissors-bite side during natural mastication in daily life. No temporomandibular disorder signs or symptoms were observed by the questionnaire and in the clinical examination.

Treatment objectives

The patient was given the diagnosis of an Angle Class II Division 1 malocclusion with bimaxillary protrusion, severe crowding of the anterior teeth, scissors-bite of the second molar on the left side, root damage of the maxillary second molars caused by the impacted third molars, and excessive tilting of the impacted mandibular third molars on both sides. The treatment objectives were to improve lip protrusion and crowding of the anterior teeth, erupt and align the impacted third molars, and achieve a good facial profile and functional occlusion.

We planned to extract the restored maxillary second premolars on both sides to keep the first premolars in good condition and to use miniscrews to reinforce the anchorage of the maxillary molars ( Fig 4 ). We also chose to extract the maxillary second molars on both sides because the panoramic photograph indicated root damage. Extractions of the root canal-filled and restored mandibular first molar on the right side, the mandibular second premolar, and the mandibular second molar on the left side were performed to erupt and align the impacted mandibular third molars with excessive mesial tilting on both sides.