Introduction

Mice with brachymorphism (bm) have defective chondrogenesis, including abnormal growth of the spheno-occipital synchondrosis. Malocclusion (anterior transverse crossbite) sometimes spontaneously occurs in inbred BALB/c- bm/bm mice, before the mandibular incisors erupt and make contact with the maxillary incisors. The aim of this study was to determine whether functional lateral loads to incisors promote anterior transverse crossbites in BALB/c- bm/bm mice.

Methods

BALB/c- bm/bm mice with normal occlusion (normal group), BALB/c- bm/bm mice with malocclusion in which the incisors were not cut (mal group), and BALB/c- bm/bm mice in which the incisors had been cut to eliminate the functional lateral load during continued growth (mal-cut group) were used. We examined the amounts of shift of the maxillary and mandibular incisors in each group using radiographic images.

Results

The amount of shift of the maxillary incisors in the mal group was significantly greater than that in normal group. The total amount of shift from the maxilla to the mandible in the mal group was significantly greater than in the normal and mal-cut groups.

Conclusions

The results suggest that a continuous functional lateral load to the incisors is strongly related to promoting and worsening anterior transverse crossbite in BALB/c- bm/bm mice.

Murine brachymorphism (bm) is characterized by a dome-shaped skull, a short and thick tail, and shortened but not widened limbs. Cartilage in brachymorphic mice contains normal levels of glycosaminoglycans (GAGs), although the GAGs are undersulfated. Mutation of the gene encoding sulfurylase kinase results in deficient glycosylation of GAGs, abnormal endochondral growth, and the brachymorphic phenotype. This phenotype is inherited as an autosomal recessive gene.

BALB/c- bm/bm mice ( bm homozygotes) are generated by outbreeding C57BL- bm/bm mice with the BALB/c lineage. Our histologic examination of condylar cartilage of BALB/c- bm/bm mice showed that the cartilage was thinner than that of BALB/c mice, and that it had an unclear zone of hypertrophic chondrocytes and contained less keratan sulfate and chondroitin sulfate. Additionally, it was shown that chondroitin sulfate and keratan sulfate were undersulfated in the spheno-occipital synchondrosis of the cranial base of BALB/c- bm/bm mice in a histochemical study. Histologic study of the spheno-occipital synchondrosis of the cranial base of BALB/c- bm/bm mice showed that the columns of chondrocytes were arranged irregularly, a bipolar column of chondrocytes was not seen, and normal endochondral growth was disturbed. These findings seem to explain why anteroposterior growth of the cranial base of BALB/c- bm/bm mice is inferior.

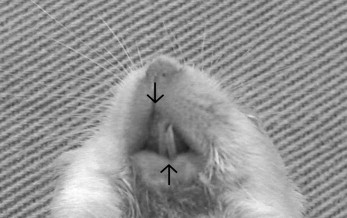

Malocclusion (anterior transverse crossbite) spontaneously occurs in about 10% of inbred BALB/c- bm/bm mice ( Fig 1 ). However, anterior transverse crossbite does not occur in mice with the same brachymorphic mutation as that in C57BL- bm/bm mice. It also does not occur in nonbrachymorphic mice such as BALB/c-+/+ and BALB/c- bm /+ mice ( bm heterozygotes).

The reason that anterior transverse crossbite spontaneously occurs in some BALB/c- bm/bm mice has not been clarified yet. It was shown that normal endochondral growth was disturbed in the spheno-occipital synchondrosis and condylar cartilage in BALB/c- bm/bm mice; this might be a reason that transverse crossbite spontaneously occurs in some BALB/c- bm/bm mice. Additionally, it is speculated that anterior transverse crossbite might occur in BALB/c- bm/bm mice when other environmental or congenital factors are added.

In this study, we hypothesized that an environmental factor—functional lateral load to incisors—promotes and worsens anterior transverse crossbite in BALB/c- bm/bm mice. To prove this, we investigated the amounts of shift between the maxillary and mandibular incisors using radiographic images obtained from BALB/c- bm/bm mice in which the functional lateral shift of the incisors remained or had been eliminated.

Material and methods

By means of outbreeding between brachymorphic mice of the C57BL strain and normal mice of the BALB/c strain, the bm gene was successfully transferred to the BALB/c mice. We had repeated back-crossing between the outbred brachymorphic mice and the BALB/c mice 9 times. The mice were housed in a room controlled for temperature (25°C), humidity (50%), and light (12 hours per day); they were permitted cage activities and given standard amounts of crushed pellet food and fresh water.

The mice were divided into the following groups: BALB/c- bm/bm mice with normal occlusion (normal group; females, n = 10), BALB/c- bm/bm mice with malocclusion (anterior transverse crossbite) (mal group; females, n = 5), and BALB/c- bm/bm mice with malocclusion in which the incisors had been cut to eliminate the functional lateral load when the mandibular incisors had just made contact with the maxillary incisors at 1 to 2 weeks of age (mal-cut group; females, n = 9). Malocclusion was noted before the incisors erupted. We distinguished between BALB/c- bm/bm mice with normal occlusion and those with anterior transverse crossbite, and classified the mice with malocclusion into 2 groups—mal-cut and mal—at random when the incisors started to erupt. All mice in the 3 groups were killed at 13 weeks of age.

The amounts of shift between the maxillary and mandibular incisors were examined by using radiographic images. A mouse was placed in the prone position on the X-ray jig, and the line between both meatus acusticus externus was made parallel to the headfilm.

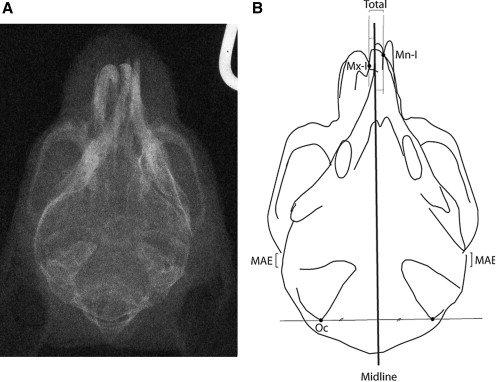

Mental-parietal (up-and-down) headfilms (dental image Insight, 31 × 40 mm, Kodak, Rochester, NY) were taken ( Fig 2 , A ) . For the radiographic images, a radiographic aperture (XED125M, Shimazu, Kyoto, Japan) with 60 kVp, 12.5 A, and a fixed focus film distance (1050 mm) were used.

The headfilms were digitized, scanned, and enlarged to 1000% to increase the precision of the measurements with Photoshop Elements (Adobe Systems, San Jose, Calif). First, we measured 2 cephalometric variables: (1) amounts of shift of the maxilla (contact point of left and right maxillary incisors) from the midline (the perpendicular bisector for the line segment between the left and right posterior apices of the external occipital crest) and (2) amounts of shift of the mandible (contact of left and right mandibular incisors) from the midline ( Fig 2 , B ). Then we calculated the total amounts of shift from the maxillary to the mandibular incisors. These procedures were reviewed and approved by the Animal Care and Use Committee of Hokkaido University.

To check for measurement error, 3 examiners (Y.T., T.S.K., Y.S-K.) measured the variables twice on different days, and means values for each animal were obtained. The kappa statistics showed no statistically significant differences among intraexaminer and interexaminer measurements.

Statistical analysis

The relative amounts of shift for each group were analyzed statistically. One-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) was used for comparison of cephalometric values among the normal, mal, and mal-cut groups. This analysis was performed by using the SPSS statistical package (version 14.0, SPSS, Chicago, Ill), with a probability level of P <0.05 considered statistically significant.

Results

The amounts of shift of the maxillary incisor were +0.20, –0.47, and –0.09 mm in the normal, mal, and mal-cut groups, respectively. There were significant differences in the amounts of maxillary shift among the groups. The shift of the maxillary incisor in the mal group was significantly greater than in normal group. There was no significant difference in the amounts of shift of the maxillary incisor from the midline between the mal and mal-cut groups.

The amounts of shift of the mandibular incisors were +0.34, +0.58, and +0.16 mm in the normal, mal, and mal-cut groups, respectively. There was no significant difference in the amounts of shift of the mandibular incisors from the midline among the groups.

The total amounts of shift from the maxilla to the mandible were 0.14, 1.05, and 0.26 mm in the normal, mal, and mal-cut groups, respectively. There was a significant difference in the total amount of shift from the maxilla to the mandible among the 3 groups. The total amount of shift from the maxilla to the mandible in the mal group was significantly greater than in the normal and mal-cut groups. There was no significant difference in the total amounts of shift from the maxilla to the mandible between the normal and mal-cut groups ( Tables I and II ) .