An atrophic mandible presents a number of reconstructive challenges because of its altered anatomy and physiology. Progressive erosion leads to loss of form and function and predisposes patients to fractures that are difficult to treat. State-of-the-art reconstruction revolves around restoration of mandibular volume in conjunction with placement of endosseous titanium implants to stabilize bone grafts and provide a foundation for prosthetic and functional esthetic rehabilitation. Although the literature is replete with multiple techniques to achieve these goals, the most predictable contemporary protocol involves harvesting of autogenous iliac crest, extraoral bone graft augmentation, and delayed placement of dental implants in conjunction with prosthetic treatment planning.

Etiopathogenesis/Causative Factors

Although oral health awareness and prevention of dental disease have reduced rates of tooth loss and complete edentulism in developed countries, growth of the elderly population is likely to be associated with an increase in the overall number of edentulous individuals. The loss of teeth initiates a sequence of physiologic events that leads to the progressive loss of alveolar bone in a predictable pattern that is accelerated by the use of conventional denture prostheses. Over time, this leads to both functional and esthetic changes related to denture stability, chewing, swallowing, speech, and facial soft tissue support. Initially, these alterations may be managed with traditional pre-prosthetic, surgical, and prosthetic techniques, which may allow interim rehabilitation. However, as resorption of the mandible progresses and becomes more severe, these procedures become less successful.

Pathologic Anatomy

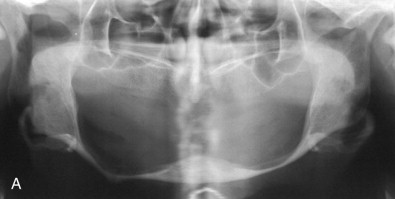

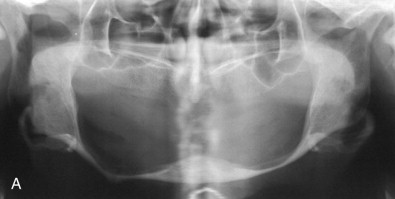

The progression of alveolar and mandibular atrophy has been well described in the literature. Many different values (including height <10 mm) are used for the definition of an “atrophic” mandible. Because the alveolar bone is resorbed and the vertical dimension of the mandible is reduced to less than 10 mm, it provides poor bone stock for implant restoration, is overly thin and more prone to fracture, provides a limited platform for traditional dentures, and is in a poor relationship to the maxilla ( Fig. 22-1 ).

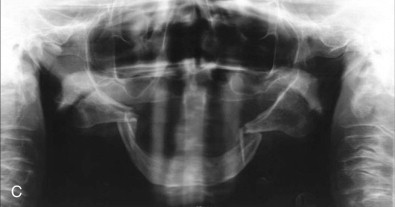

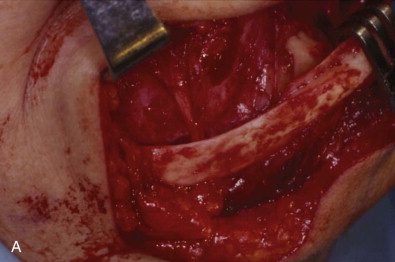

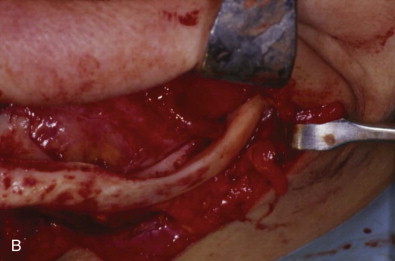

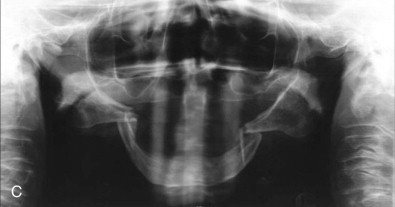

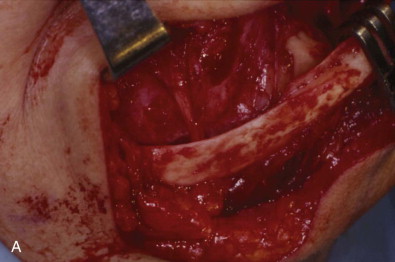

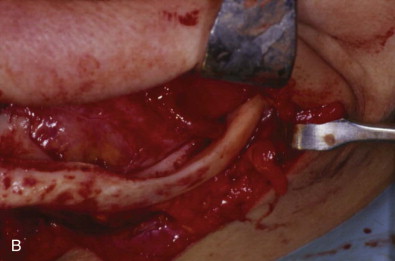

Mandibular resorption leads to additional anatomic and phenotypic alterations beyond the change in dimension. There is an associated reduction in mucosal surface area, atrophy, and relatively superficial repositioning of the oral and facial musculature, as well as the inferior alveolar neurovascular bundle ( Fig. 22-2 ). Additionally, erosion of the cancellous alveolar bone leaves a dense and primarily cortical basal strut in place. Facial changes include a reduction in vertical dimension and conversion to a class III prognathic relationship secondary to both the pattern of resorption and autorotation of the mandible.

Physiologic changes also occur and may be relevant to the pathology of mandibular resorption, as well as pose important considerations for reconstructive procedures. The aging mandible is associated with decreased osteogenic potential, probably because of reduced peripheral stem cell populations. Moreover, progressive narrowing of the inferior alveolar artery leads to a transition from a centrifugal to a centripetal blood supply of the mandible, thereby resulting in higher relative importance of the periosteum and surrounding tissues for vascular supply.

Pathologic Anatomy

The progression of alveolar and mandibular atrophy has been well described in the literature. Many different values (including height <10 mm) are used for the definition of an “atrophic” mandible. Because the alveolar bone is resorbed and the vertical dimension of the mandible is reduced to less than 10 mm, it provides poor bone stock for implant restoration, is overly thin and more prone to fracture, provides a limited platform for traditional dentures, and is in a poor relationship to the maxilla ( Fig. 22-1 ).

Mandibular resorption leads to additional anatomic and phenotypic alterations beyond the change in dimension. There is an associated reduction in mucosal surface area, atrophy, and relatively superficial repositioning of the oral and facial musculature, as well as the inferior alveolar neurovascular bundle ( Fig. 22-2 ). Additionally, erosion of the cancellous alveolar bone leaves a dense and primarily cortical basal strut in place. Facial changes include a reduction in vertical dimension and conversion to a class III prognathic relationship secondary to both the pattern of resorption and autorotation of the mandible.

Physiologic changes also occur and may be relevant to the pathology of mandibular resorption, as well as pose important considerations for reconstructive procedures. The aging mandible is associated with decreased osteogenic potential, probably because of reduced peripheral stem cell populations. Moreover, progressive narrowing of the inferior alveolar artery leads to a transition from a centrifugal to a centripetal blood supply of the mandible, thereby resulting in higher relative importance of the periosteum and surrounding tissues for vascular supply.

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses