In a young woman, aged 18 years 8 months, who had an anterior open bite and anterior spacing, the right and left mandibular first molar extraction spaces were closed by protraction of the second and third molars without reciprocal retraction of the incisors and the premolars. The amounts of protraction for the second molars were 12 mm on the right side and 11 mm on the left side. Two miniscrews were inserted into the mesiobuccal side of the edentulous spaces, and 2 more screws were inserted into the anterior sites after removing previous miniscrews. In addition, 4 miniscrews were inserted into the buccal and palatal sides between the first and second maxillary molars to intrude the maxillary posterior teeth, which had extruded into the missing mandibular spaces. Careful biomechanical consideration was used to prevent extrusion of the molars and worsening of the anterior open bite from protraction of the posterior teeth. Ultimately, the anterior open bite was corrected by both intrusion of the maxillary molars and extrusion of the maxillary anterior teeth. Excellent occlusion and correction of the anterior open bite were achieved without tipping, rotation of the posterior teeth, or other problems. The right mandibular third molar, which had been impacted at the beginning of treatment, erupted into the second molar space and functioned properly. At the 1-year follow-up examination, the patient had a slight anterior open bite, but closure of the first molar extraction spaces was well maintained.

When a mandibular first molar is lost, orthodontic replacement with second and third molars would be an excellent treatment option if success were guaranteed. Stepovich presented the possibilities of these methods without severe complications, such as root resorption and tipping of adjacent teeth. At that time, however, the space was closed mostly by reciprocal movement of the anterior and posterior teeth, because no temporary skeletal anchorage devices were available. Roberts et al used endosseous implants placed in the retromolar area to close missing first molar spaces by mesial movement of the mandibular molars. In recent years, orthodontic miniscrews, which are more convenient, simple, and cheaper than endosseous implants, have been used widely. Kyung et al reported a 9-mm mesial movement of mandibular second molars, and Nagaraj et al reported an 8-mm movement using miniscrews to close bilateral missing mandibular first molar spaces. Kravitz and Jolley discussed problems, such as buccal proclination, during mandibular molar protraction with miniscrews.

Treatment is difficult when pure protraction of the second and third molars is required without retraction of the anterior and premolar teeth. In addition, treatment would be more complicated if the patient had an anterior open bite and long edentulous spaces.

Our patient was missing both mandibular first molars, and the maxillary first molars had extruded into the edentulous mandibular spaces. In addition, the patient had an anterior open bite. Protraction of the mandibular second molars was necessary, since there was no protrusion or crowding of the anterior teeth.

After treatment, good occlusion and the correction of the anterior open bite were achieved. The amounts of protraction of the mandibular second and third molars were 12 mm on the right side and 11 mm on the left side.

Diagnosis and etiology

A young woman, aged 18 years 8 months, sought an orthodontic evaluation with chief complaints of an anterior open bite and spacing. She also wanted to close the missing mandibular first molar spaces by orthodontic tooth movement, if possible. The right and left mandibular first molars had been extracted 4 months previously, because of severe caries.

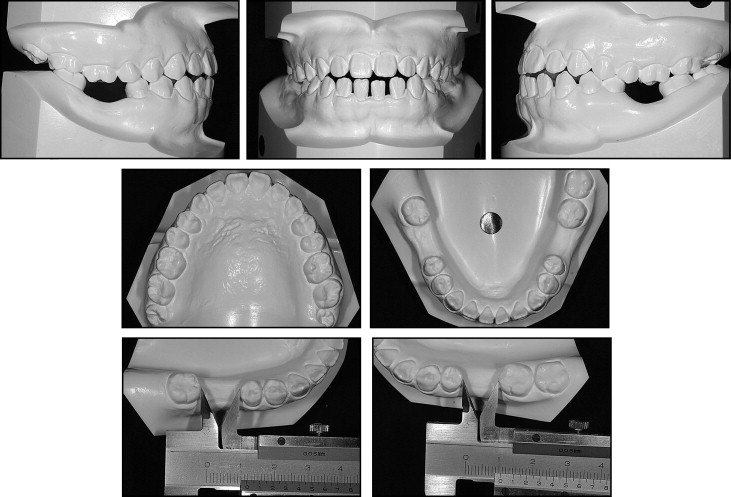

The patient had a straight profile with a slightly protruded chin. Vertically, she had a long face with a high gonial angle. No remarkable facial asymmetry was seen ( Fig 1 ). Intraorally, she had anterior spacing in the mandibular arch, an anterior open bite (−1.0 mm of overbite), and an end-to-end incisor relationship (0.0 mm of overjet). Both mandibular first molars were missing. The dental casts showed that the lengths of the mandibular edentulous spaces were 11.5 mm on right side and 10.5 mm on the left side ( Fig 2 ). The right and left maxillary first molars had extruded into the missing mandibular first molar edentulous sites. Without intrusion of these maxillary molars, protraction of the mandibular second molars would be difficult because of their potential contact against the maxillary molars.

The maxillary dental midline was coincident with the facial midline, and the mandibular dental midline was deviated 1.0 mm to the left. The canines exhibited a mild Class II occlusion, especially on the right side. To achieve a Class I occlusal relationship, the second molars would need to be protracted beyond the first molar extraction sites.

A panoramic radiograph showed long edentulous spaces and a slight mesial tilt of the left second molar in the mandible. The right third molar was impacted, but the developing status was good ( Fig 3 ). Lateral cephalometric analysis ( Fig 4 , Table ) showed a mild skeletal Class III relationship (ANB angle, 3.0°; Wits appraisal, −4.5 mm). Vertically, the patient showed a long facial tendency (FMA, SN-MP angle, and ANS-Me/N-ANS) with an anterior open bite. Soft-tissue analysis showed a slight protrusion of the lower lip (lower lip to E-line, 2.5 mm).

| Measurement | Normal | 1 SD | Pretreatment | Posttreatment | 1 year after retention |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Maxillomandibular relationships | |||||

| SNA (°) | 83.1 | 2.8 | 80.0 | 80.0 | 80.0 |

| SNB (°) | 79.5 | 2.7 | 77.0 | 77.5 | 77.0 |

| ANB (°) | 3.6 | 1.5 | 3.0 | 2.5 | 3.0 |

| Wits appraisal (mm) | −1.3 | 2.6 | −4.5 | −5.0 | −4.5 |

| Vertical skeletal relationships | |||||

| Mandibular plane to SN (°) | 36.0 | 3.6 | 42.5 | 42.5 | 43.0 |

| FMA (°) | 29.0 | 3.6 | 37.0 | 37.0 | 37.5 |

| Gonial angle (°) | 126.6 | 6.0 | 125.0 | 125.5 | 125.0 |

| ANS-Me/N-ANS | 1.2 | 0.1 | 1.6 | 1.6 | 1.6 |

| Dental relationships | |||||

| U1 to SN (°) | 105.3 | 5.1 | 102.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 |

| U1 to FH (°) | 112.3 | 5.1 | 108.0 | 106.0 | 106.0 |

| FMIA (°) | 60.3 | 5.4 | 50.0 | 48.5 | 48.0 |

| IMPA (°) | 90.7 | 5.6 | 92.0 | 90.5 | 90.5 |

| Interincisal angle (°) | 128.0 | 8.0 | 123.0 | 124.5 | 124.0 |

| Soft tissues | |||||

| Upper lip to E-line (mm) | −1.0 | 0.86 | −1.5 | −1.0 | −1.0 |

| Lower lip to E-line (mm) | 0.0 | 0.56 | 2.5 | 2.5 | 2.0 |

The functional assessment showed no remarkable discrepancy between centric occlusion and centric relation, and no apparent signs and symptoms of temporomandibular joint dysfunction. There were no other medical or dental problems.

Treatment objectives

We planned to maintain the anteroposterior position of the maxillary incisors, since there was no significant facial profile problem, except for the slight protrusion of the lower lip. The main treatment objectives consisted of protracting the mandibular second and third molars to close the missing first molar spaces and to correct the anterior open bite. Mandibular anterior spacing would be closed by retraction of the incisors and protraction of the premolars, because the protraction was needed to improve the existing Class II canine relationship. Vertical facial height would be maintained, because of the original long-face tendency.

Treatment objectives

We planned to maintain the anteroposterior position of the maxillary incisors, since there was no significant facial profile problem, except for the slight protrusion of the lower lip. The main treatment objectives consisted of protracting the mandibular second and third molars to close the missing first molar spaces and to correct the anterior open bite. Mandibular anterior spacing would be closed by retraction of the incisors and protraction of the premolars, because the protraction was needed to improve the existing Class II canine relationship. Vertical facial height would be maintained, because of the original long-face tendency.

Treatment alternatives

Spaces caused by missing mandibular first molars can be corrected by prosthetic bridges, dental implants, autotransplantation of third molars, or mesial orthodontic movement of second and third molars. Prosthetic bridges offer the advantage of short treatment time but must be accompanied by significant tooth preparation. Dental implants permit conservation of tooth structure but require surgery. Autotransplantation also requires surgery, and successful transplantation cannot be guaranteed. To improve facial esthetics and skeletal discrepancies such as a protruded chin, orthognathic surgery might be another option.

Our patient finally chose orthodontic replacement, because she wanted to correct additional tooth-position problems, including anterior spacing and an anterior open bite. She also hoped to avoid surgical trauma. The patient rejected orthognathic surgery, because she did not want dramatic changes in facial appearance and extensive surgical trauma.

Treatment progress

First, a labiolingual wire (0.9 mm stainless steel) was attached to several other teeth to reinforce anchorage and intrude the maxillary right and left first molars with an elastic thread ( Fig 5 ). This technique intruded the maxillary first molars that were initially extruded into the missing mandibular first molar spaces. Preadjusted edgewise appliances with 0.018-in slots were bonded to the mandibular teeth after the maxillary first molar was sufficiently intruded. After leveling and alignment, orthodontic miniscrews (6.0 mm long, 1.5 mm diameter; Orlus, Seoul, Korea) were placed into the mesiobuccal sides of both missing mandibular first molar spaces under local anesthesia ( Fig 6 ). Two weeks after placement, an elastic module (force, 150 g) was connected from the miniscrews to the hook of the bracket attached to both the right and left second molars. A 0.016 × 0.022-in heat-treated stainless steel wire was used as a working wire, and the right and left mandibular second molars were protracted with sliding mechanics.