Introduction

Defining the best treatment for maxillary lateral incisor agenesis is a challenge. Our aim in this study was to determine, with the evidence available in the literature, the best treatment for maxillary lateral incisor agenesis in the permanent dentition, evaluating the esthetic, occlusal (functional), and periodontal results between prosthetic replacement and orthodontic space closure.

Methods

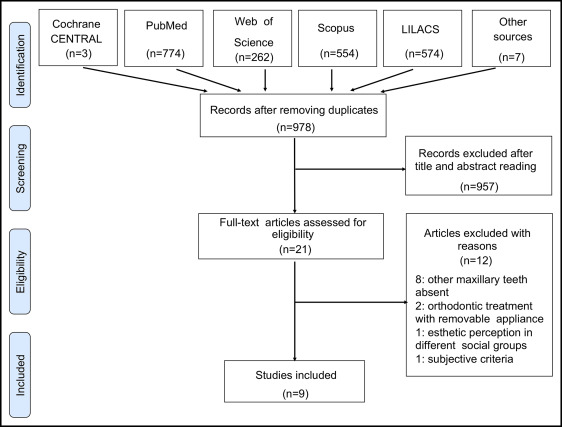

Electronic databases (CENTRAL, PubMed, Web of Science, Scopus, and LILACS) were searched in September 2014 and updated in January 2015, with no restriction on language or initial date. A manual search of the reference lists of the potential studies was performed. Risk of bias was assessed by the Newcastle Ottawa Scale.

Results

The search identified 2174 articles, of which 1196 were excluded because they were duplicates. Titles and abstracts of 978 articles were accessed, and 957 were excluded. In total, 21 articles were read in full, and 9 case-control studies were included after applying the inclusion and exclusion criteria. Data were extracted from the articles selected, and a table was compiled for comparison and analysis of the results. There were no randomization and blinding, and the risk of bias evaluation found gaps in compatibility and outcome domains in almost all selected studies.

Conclusions

Tooth-supported dental prostheses of maxillary lateral incisor agenesis had worse scores in the periodontal indexes than did orthodontic space closure. Space closure is evaluated better esthetically than prosthetic replacements, and the presence or absence of a Class I relationship of the canines showed no relationship with occlusal function or with signs and symptoms of temporomandibular disorders.

Highlights

- •

Most data on maxillary lateral incisor agenesis treatment come from retrospective studies.

- •

Class I canines were compared with maxillary canines moved to lateral incisor positions.

- •

No functional advantage to Class I canines was found.

- •

Periodontal scores were worse with tooth-supported prostheses than with space closure.

- •

The esthetic limitations of dental prostheses elicit greater criticism than space closure.

The ideal orthodontic treatment for maxillary lateral incisor agenesis remains a controversial topic in both academic and clinical fields, even after more than 5 decades of debate. The central point of this lack of consensus is the decision between opening space for prosthetic replacement of the absent teeth or orthodontically closing the spaces, followed by anatomic recontouring of the canines.

Some authors have considered that certain clinical characteristics must be analyzed before deciding upon the best therapeutic alternative, such the patient’s age, type of sagittal malocclusion, presence or absence of crowding in both dental arches, and type of facial profile.

Those who defend prosthetic replacement of the absent incisors believe that canine guidance is ideal for a long-term, healthy occlusion. These authors have also reported the difficulty in obtaining adequate esthetics when the canine substitutes for the lateral incisor because of the differences in color, shape, or root volume. Conversely, those who defend orthodontic space closure argue that the periodontal conditions are better than those that are observed in patients with a fixed or removable prosthesis. Furthermore, the esthetic outcome with space closure is more natural if the orthodontist performs the correct enameloplasty in the canine and adequately controls the lingual root torque.

There are numerous articles on this subject, but most are narrative reviews, articles of opinion, case series, and case reports. The respective 1975 and 1976 comparative studies of Nordquist and McNeill and Senty may be considered classics because of their pioneering nature, although in one, the analysis was eminently subjective. In 2000, Robertsson and Mohlin, taking advantage of the technical improvements in dental prostheses (porcelain bonded to gold and resin-bonded bridge), conducted a study that also occupies an important place in the dental literature. However, none of these 3 studies evaluated implant-supported crowns that are currently considered the ideal prosthetic option for absent teeth, despite the probable esthetic problems of gingival retraction, interdental black triangles, and infraocclusion.

Andrade et al conducted a systematic review in 2011 (published in 2013) and found no scientific evidence to support any treatment option for maxillary lateral incisor agenesis because they did not identify any randomized clinical trial (RCT) or quasi-RCT. Nevertheless, these authors recognized the high complexity of this clinical problem because of the different variables involved and suggested that the best treatment might never be found if only the evidence from RCTs were considered. In accordance with the study of Papageorgiou et al, when RCTs are not feasible or inappropriate, the clinical decision should be made on sound reasoning and scientific evidence over well-conducted prospective non-RCTs that can provide complementary evidence.

Therefore, the aim of this systematic review was to determine with the evidence available the best treatment alternative for patients with maxillary lateral incisor agenesis by comparing orthodontic space closure and implant-supported and tooth-supported dental prostheses by assessing studies that evaluated their esthetic, occlusal (functional), and periodontal results.

Material and methods

This systematic review was carried out according to the guidelines of the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA statement) and the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (version 5.1.0). No protocol registration was performed.

Eligibility criteria

All studies that evaluated and compared the results—occlusal (functional), periodontal, or esthetic aspects—of the different prosthetic treatments with orthodontic space closure for patients with maxillary lateral incisor agenesis, unilateral or bilateral, in the permanent dentition were included. For prosthetic replacements, no distinction was made between those who had a previous orthodontic intervention or not. In the space closure modality, only patients treated with fixed orthodontic appliances were included.

Other exclusion criteria were as follows: tooth loss from trauma or caries (because these could cause bone loss and confound the periodontal results), absence of other teeth in the maxilla, other dental anomalies (supernumerary, impacted, or ectopic teeth), interceptive or provisional treatments, patients with syndromes or cleft lip and palate, orthognathic surgery, review articles, opinion articles, case reports, descriptions of techniques, subjective evaluations of results without statistical analysis, studies of esthetic perception with images that were manipulated on computers, and studies that did not have a direct comparison of the treatment modalities.

Information sources, search strategy, and study selection

The following electronic databases were searched in September 2014 without restrictions on language or initial date: Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials, MEDLINE via PubMed, Web of Science, Scopus, and LILACS. The search strategies were obtained under the guidance of an experienced librarian using a process of identification of key words, expressions, and their possible combinations to encompass the most studies related to our objectives. Table I illustrates the search strategy used in PubMed (see also the Supplemental Table ). A manual search of the reference lists of the potential studies and an additional electronic search to update the results were performed in January 2015.

| Database | Search strategies |

|---|---|

| Pubmed | (“upper lateral incisor”[tiab] OR “maxillary lateral incisor”[tiab] OR incisor[MH] OR incisor[tiab]) AND (anodontia[mh] OR anodontia[tiab] OR “teeth agenesis”[tiab] OR “tooth agenesis”[tiab] OR hypodontia[tiab] OR oligodontia[tiab] OR “dental agenesis”[tiab] OR “partial anodontia”[tiab] OR “missing teeth”[tiab] OR “missing tooth”[tiab] OR “absent teeth”[tiab] OR “absent tooth”[tiab] OR “congenitally missing”[tiab] OR “congenitally absent”[tiab] OR missing[tiab] OR absent[tiab]) AND (Orthodontics[MH] OR “orthodontic treatment”[tiab] OR “orthodontic therapy”[tiab] OR Tooth movement[MH] OR “orthodontic movement”[tiab] OR “teeth movement”[tiab] OR Orthodontic space closure[MH] OR “orthodontic space closure”[tiab] OR “orthodontic dental space closure”[tiab] OR “canine substitution”[tiab] OR “mesial movement of canine”[tiab] OR “mesial movement of cuspid”[tiab] OR Dental implants[MH] OR “dental implant”[tiab] OR “single tooth implant”[tiab] OR “single-tooth implant”[tiab] OR “single-tooth implants”[tiab] OR “single-tooth dental implant”[tiab] OR Denture, partial, fixed[MH] OR “Denture partial fixed”[tiab] OR fixed bridge* OR “fixed partial denture”[tiab] OR pontic[tiab] OR Denture, partial, removable[MH] OR “denture removable partial”[tiab] OR Denture, partial, fixed, resin-bonded[mh] OR “maryland bridge dental”[tiab] OR “resin-bonded bridge”[tiab] OR “resin-bonded fixed partial denture”[tiab] OR “resin-bonded acid etched fixed partial denture”[tiab] OR Dental prosthesis[MH] OR “dental prosthesis”[tiab] OR “prosthetic replacement”[tiab] OR Dental prosthesis, implant-supported[MH] OR “prosthesis implant-supported dental”[tiab]) |

Duplicate articles were eliminated. The titles and abstracts were read independently by 2 reviewers (G.S.S. and N.V.A.), and the articles that had characteristics compatible with those of the inclusion criteria were selected so that the full texts were examined to confirm their eligibility.

Data items and collection

From the articles included, the data were organized in tables, and this was also done independently by the some 2 reviewers. Ages of the participants and follow-ups were given in decimal years. Disagreements between the 2 reviewers in these 2 stages were resolved in a consensus meeting with a third researcher (C.T.M.). When a lack of data was observed in an article, an attempt was made to obtain the information by contacting the authors by e-mail.

Risk of bias in individual studies

To assess the risk of bias of the retrospective studies selected, an adaptation of the Newcastle-Ottawa Scale was used with 9 specific domains. This was a “star” system in which a star is marked in each domain if this is identified as satisfactory in the study. Two reviewers (G.S.S. and N.V.A.) independently evaluated the risk of each study, and disagreements were resolved in a meeting with a third researcher (C.T.M.).

Summary measures and approach to synthesis

As a result of the heterogeneity among the studies included in this systematic review, particularly in their designs and the variables evaluated, it was not feasible to perform a meta-analysis. A qualitative synthesis was performed by comparing the results from individual studies according to the groups evaluated (with statistical significance). The incorporation of the risk of bias into the qualitative synthesis was not possible because of the heterogeneity among the studies and the characteristics described.

Results

Study selection and characteristics

The initial search identified 2174 articles, but 1196 were excluded because they were duplicates. The titles and abstracts of the 978 remaining articles were accessed, and 957 were excluded because they were not related to the subject or did not fulfill the eligibility criteria. Twenty-one articles were read in full, and 12 were excluded for the following reasons: absence of teeth in the maxilla other than lateral incisors, orthodontic treatment with removable appliances, or comparison of the esthetic demands of different social groups without distinction between the types of treatment, and occlusal and esthetic descriptive evaluations with a highly subjective nature and without quantitative criteria. The 9 articles that met the inclusion criteria were case-control studies that compared the results of different types of treatment and were included in this review ( Fig ).

Three studies compared the periodontal and occlusal results in patients with space closure with tooth-supported and implant-supported dental prostheses. One study also compared the esthetic results, evaluated by the patients themselves, and 2 studies evaluated signs and symptoms of temporomandibular disorders (TMDs).

The other 6 studies compared only the esthetic results of the different types of treatment. In 3 studies, dental professionals and laypersons evaluated photographs without knowing the type of treatment performed. In the other 3 studies, different esthetic criteria were used, such as width-to-height ratio, gingival zenith of the maxillary lateral incisor, golden proportion in the 6 anterior teeth, and apparent contact dimension in the same sample, varying only between subjects with unilateral or bilateral agenesis. This information was obtained from an author by e-mail contact, and data not reported in the articles were obtained: ages of the subjects and time of posttreatment evaluation ( Table II ). This same research group also conducted the study that compared the functional and periodontal aspects for both space closure and implant-supported dental prostheses.

| Study | Design | Participants (sex): treatment modalities | LI agenesis (bilateral or unilateral) | Patients age (y): mean (range) | Objective | Parameters evaluated | Method of measurement | Statistical analysis (level of significance) | Results | Follow-up: mean (range) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nordquist and McNeill, 1975 | Case control | 33 patients (not reported): not reported | 25 patients (bilateral) 8 patients (unilateral) |

Not reported | To compare OSC, FPD, and RPD | Occlusal function Periodontal status |

Clinical examination | F ratio, t test ANOVA for 1-way design ( P = 0.01) |

Periodontal status (OSC>RPD=FPD) Occlusal function (OSC=FPD=RPD) |

9.7 y (2.3-25.5 y) |

| Robertsson and Mohlin, 2000 | Case control | 50 patients (M, 14; F, 36): 30 OSC, 20 FPD |

39 patients (bilateral) 11 patients (unilateral) |

25.8 y (18.4-54.9 y) |

To compare OSC and FPD | Occlusal function Signs and symptoms of TMDs Periodontal status Esthetics |

Clinical examination and questionnaire | t test chi-square ( P = 0.05) |

Occlusal function (OSC=FPD) Esthetic (OSC>FPD) Periodontal status (OSC>FPD) |

7.1 y (0.5-13.9 y) |

| Armbruster et al, 2005 | Case control | 12 subjects (not reported): 3 MB, 3 DI, 3 OSC, 3 ND Evaluators: 43 orthodontists, 140 general dentists, 29 specialists, 40 laypersons |

6 patients (bilateral) 3 patients (unilateral) |

Not reported | To compare OSC, DI, MB, and ND | Esthetics | Intrabuccal photos | 2-way ANOVA 1-way ANOVA Student Newman-Keuls ( P = 0.05) |

Laypersons (OSC>ND>MB>DI) General dentists (ND>OSC>MB>DI) |

Not reported |

| Thams et al, 2009 | Case control | 12 subjects (not reported): 2 MB, 3 DI, 4 OSC, 3 NT Evaluators: 15 orthodontists, 15 general dentists, 15 laypersons |

Not reported (bilateral and unilateral) | Not reported | To compare OSC, DI, MB, and NT | Esthetics | Intrabuccal photos | ANOVA ( P = 0.05) |

All groups of evaluators (OSC>DI>MB>NT) |

Not reported |

| De Marchi et al, 2012 | Case control | 68 subjects (M, 52; F, 16): 26 OSC, 20 DI, 22 ND | 27 patients (bilateral) 19 patients (unilateral) |

OSC: 24.9 y (14.1-41.1) DI: 25.1 y (19.0-45.1) ND: 21.3 y (19.1-26.1) |

To compare OSC, DI, and ND | Periodontal status Signs and symptoms of TMDs |

Clinical examination and questionnaire | Fisher exact test Shapiro-Wilk Mann-Whitney test Nonparametric Kruskal-Wallis ( P = 0.05) |

Periodontal status: plaque index, bleeding on probing, probing depth, gingival recession (OSC=DI=CG) PIS (OSC=CG>DI) Signs and symptoms of TMDs (OSC=DI=CG) |

OSC: 3.9 y DI: 3.5 y |

| Pini et al, 2012 | Case control | 52 subjects (not reported): 18 OSC, 10 DI, 24 ND | 28 patients (bilateral) |

OSC: 32.4 y DI: 32.7 y ND: 21.3 y |

To compare OSC, DI, and ND | Esthetics | Dental cast | Shapiro-Wilk Wilcoxon Kruskal-Wallis t test ANOVA ( P = 0.05) |

WHR: CI, LI, C (OSC=DI=ND) GZ: LI (OSC=DI=ND) |

OSC: 5 y DI: 3 y |

| Pini et al, 2012 | Case control | 48 patients (M, 9; F, 39): 28 OSC, 20 DI 25 subjects: ND |

28 patients (bilateral) 20 patients (unilateral) |

OSC: 24.9 y (14.1-41.1) DI: 25.1 y (19.0-45.1) ND: 21.3 y (19.1-26.1) |

To compare OSC, DI, and ND | Esthetics | Dental cast | Shapiro-Wilk Wilcoxon Kruskal-Wallis Mann-Whitney U post hoc Friedman Post hoc Wilcoxon ( P = 0.05) |

GP Yes CI:LI (DI=ND>OSC) No LI:C (DI=ND=OSC) WHR: LI (mean) (DI=ND<OSC) |

OSC: 4.7 y DI: 2.7 y |

| Pini et al, 2013 | Case control | 52 subjects (not reported): 18 OSC, 10 DI, 24 ND | 28 patients (bilateral) |

OSC: 32.4 DI: 32.7 y ND: 21.3 y |

To compare OSC,DI, and ND | Esthetics | 3D digital image from dental cast | Shapiro-Wilk Spearman correlation Kruskal-Wallis ( P = 0.05) |

WHR: CI, LI, C (OSC=DI=ND) GZ: LI (OSC<ND=DI) ACD: (DI>OSC=ND) |

OSC: 5 y DI: 3 y |

| De-Marchi et al, 2014 | Case control | 68 subjects (M, 52; F, 16): 26 OSC, 20 DI, 22 ND Evaluators: 20 dentists, 20 laypersons, 68 patients (self-evaluation) |

27 patients (bilateral) 19 patients (unilateral) |

OSC: 24.9 y (14.1-41.1) DI: 25.1 y (19.0-45.1) ND: 21.3 y (19.1-26.1) |

To compare OSC, DI, and ND | Esthetics | Photo of smile– lower third of the face (visual analog scales) | Fischer post hoc Mann-Whitney Shapiro-Wilk t test Cronbach α ICC Kolmogorov-Smirnov Multifactorial ANOVA 1-way ANOVA Bonferroni correction ( P = 0.05) |

Laypersons and dentists (OSC=DI=ND) Self-evaluation (OSC=DI>ND) (OSC=DI) (OSC>ND) (DI=ND) |

OSC: 3.9 y DI: 3.5 y |

Risk of bias assessment in studies

The result of the risk of bias assessment with an adaptation of the Newcastle-Ottawa Scale to case-control studies showed gaps in compatibility (study controls for other factors than age) and outcome (follow-up durations) domains ( Table III ) in almost all studies. In addition to sample size calculation, random sequence generation, blinding of allocation, and blinding of measures had not been done and could have contributed to biases.

| Study | Design | Selection | Compatibility | Outcome | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Case definition | Representative of the cases | Selection of controls | Definition of controls | Study controls for age | Study controls for any additional factor | Assessment of outcome | Method of ascertainment | Follow-up duration | ||

| Nordquist and McNeill, 1975 | Case control | ★ | ★ | ★ | ★ | ★ | ||||

| Robertsson and Mohlin, 2000 | Case control | ★ | ★ | ★ | ★ | ★ | ★ | ★ | ★ | |

| Armbruster et al, 2005 | Case control | ★ | ★ | ★ | ★ | |||||

| Thams et al, 2009 | Case control | ★ | ★ | ★ | ★ | |||||

| De Marchi et al, 2012 | Case control | ★ | ★ | ★ | ★ | ★ | ★ | ★ | ||

| Pini et al, 2012 | Case control | ★ | ★ | ★ | ★ | ★ | ★ | ★ | ||

| Pini et al, 2012 | Case control | ★ | ★ | ★ | ★ | ★ | ★ | ★ | ||

| Pini et al, 2013 | Case control | ★ | ★ | ★ | ★ | ★ | ★ | ★ | ||

| De-Marchi et al, 2014 | Case control | ★ | ★ | ★ | ★ | ★ | ★ | ★ | ||

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses