Learning Objectives

After reading this chapter, the student should be able to:

- 1.

Recognize procedural accidents and describe the causes, prevention, and treatment of the following:

- a.

Pulp chamber perforation during access preparation

- b.

Ledging

- c.

Obstruction of the canal with dental materials or dentin shavings

- d.

Coronal or radicular perforation

- e.

Separated instrument

- f.

Obturation short of the prepared working length

- g.

Expression of obturation materials beyond the apex

- h.

Incomplete obturation

- i.

Vertical root fracture

- j.

Post space preparation mishaps

- a.

As can other complex disciplines of dentistry, root canal therapy can present unwanted or unforeseen challenges that can affect the prognosis. These mishaps are collectively termed procedural accidents . However, fear of procedural accidents should not deter a practitioner from performing root canal treatment if proper case selection and competency issues are observed.

Knowledge of the etiologic factors involved in procedural accidents is essential for prevention. In addition, methods of recognition and treatment and the effects of such accidents on the prognosis must be learned. Most problems can be avoided by adhering to the basic principles of diagnosis, case selection, treatment planning, access preparation, cleaning and shaping, obturation, and post space preparation.

Examples of procedural accidents include swallowed or aspirated endodontic instruments, crown or root perforation, ledge formation, separated instruments, underfilled or overfilled canals, and vertically fractured roots. A good practitioner uses knowledge, dexterity, intuition, patience, and awareness of personal limitations to minimize these accidents. When an accident occurs during root canal treatment, the patient should be informed about (1) the incident, (2) procedures necessary for correction, (3) alternative treatment modalities, and (4) the effect of this accident on the prognosis. Proper medical-legal documentation is mandatory. A successful practitioner learns from past experiences and applies them to future challenges. In addition, the practitioner who knows her or his own limitations is able to recognize potentially difficult cases and refers the patient to an endodontist. The beneficiary is the patient, who thus receives the best care.

This chapter discusses the causes, prevention, and treatment of various types of procedural accidents that may occur at different phases of root canal treatment. The effects of these accidents on the short-term and long-term prognoses also are described.

Learning Objectives

After reading this chapter, the student should be able to:

- 1.

Recognize procedural accidents and describe the causes, prevention, and treatment of the following:

- a.

Pulp chamber perforation during access preparation

- b.

Ledging

- c.

Obstruction of the canal with dental materials or dentin shavings

- d.

Coronal or radicular perforation

- e.

Separated instrument

- f.

Obturation short of the prepared working length

- g.

Expression of obturation materials beyond the apex

- h.

Incomplete obturation

- i.

Vertical root fracture

- j.

Post space preparation mishaps

- a.

As can other complex disciplines of dentistry, root canal therapy can present unwanted or unforeseen challenges that can affect the prognosis. These mishaps are collectively termed procedural accidents . However, fear of procedural accidents should not deter a practitioner from performing root canal treatment if proper case selection and competency issues are observed.

Knowledge of the etiologic factors involved in procedural accidents is essential for prevention. In addition, methods of recognition and treatment and the effects of such accidents on the prognosis must be learned. Most problems can be avoided by adhering to the basic principles of diagnosis, case selection, treatment planning, access preparation, cleaning and shaping, obturation, and post space preparation.

Examples of procedural accidents include swallowed or aspirated endodontic instruments, crown or root perforation, ledge formation, separated instruments, underfilled or overfilled canals, and vertically fractured roots. A good practitioner uses knowledge, dexterity, intuition, patience, and awareness of personal limitations to minimize these accidents. When an accident occurs during root canal treatment, the patient should be informed about (1) the incident, (2) procedures necessary for correction, (3) alternative treatment modalities, and (4) the effect of this accident on the prognosis. Proper medical-legal documentation is mandatory. A successful practitioner learns from past experiences and applies them to future challenges. In addition, the practitioner who knows her or his own limitations is able to recognize potentially difficult cases and refers the patient to an endodontist. The beneficiary is the patient, who thus receives the best care.

This chapter discusses the causes, prevention, and treatment of various types of procedural accidents that may occur at different phases of root canal treatment. The effects of these accidents on the short-term and long-term prognoses also are described.

Perforations during Access Preparation

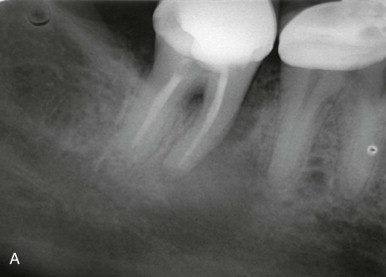

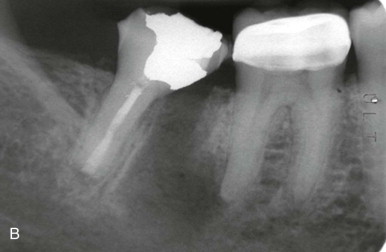

The prime objective of an access cavity is to provide an unobstructed or straight-line pathway to the apical foramen ( Fig. 19.1 ). Accidents such as excess removal of tooth structure or perforation may occur during attempts to locate canals. Failure to achieve straight-line access is often the main etiologic factor for other types of intracanal accidents.

Causes

Despite anatomic variations in the configuration of various teeth, the pulp chamber in most cases is located in the center of the anatomic crown. The pulp system is located in the long axis of the tooth. Lack of attention to the degree of axial inclination of a tooth in relation to adjacent teeth and to alveolar bone may result in either gouging or perforation of the crown or the root at various levels ( Fig. 19.2 ). After the proper access outline form has been established, failure to direct the bur parallel to the long axis of a tooth causes gouging or perforation of the root. This problem often occurs when the dentist must use the reflected image from an intraoral mirror to make the access preparation. In these situations, the natural tendency is to direct the bur away from the long axis of the root to improve vision through the mirror. Failure to check the orientation of the access opening during preparation may result in a perforation. The dentist should stop periodically to review the bur-tooth relationship. Aids for evaluating progress include transillumination, magnification, and radiographs.

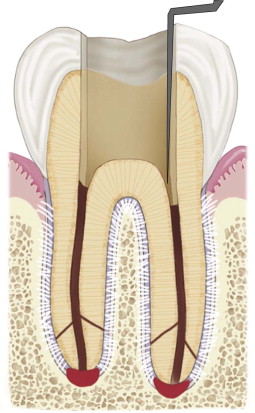

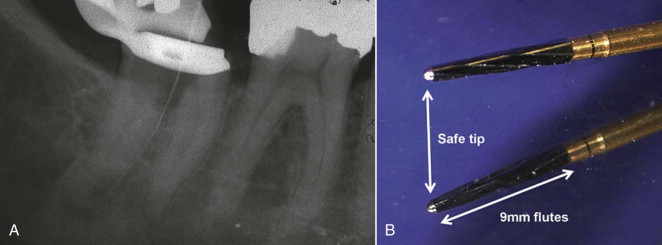

Searching for the pulp chamber or orifices of canals through an underprepared access cavity may also result in accidents. Failure to recognize when the bur passes through a small or flattened (disklike) pulp chamber in a multirooted tooth may also result in gouging or perforation of the furcation ( Fig. 19.3, A ). Use of a “safe-ended” access bur ( Fig. 19.3, B ) can prevent perforation of the chamber floor.

A cast crown often is not aligned in the long axis of the tooth; directing the bur along the misaligned casting may result in a coronal or radicular perforation.

Prevention

Clinical Examination

Thorough knowledge of tooth morphology, including both the surface and internal anatomies and their relationship, is mandatory to prevent pulp chamber perforations. Next, the location and angulation of the tooth must be related to adjacent teeth and alveolar bone to avoid a misaligned access preparation. In addition, radiographs of teeth from different angles provide information about the size and extent of the pulp chamber and the presence of internal changes such as calcification or resorption. The radiograph is a two-dimensional projection of a three-dimensional object. Varying the horizontal exposure angle provides at least a distorted view of the third dimension and may be helpful in supplying additional anatomic information. Cone beam computed tomography (CBCT) can also provide invaluable information in cases involving severe calcification or unusual canal anatomy. In complex cases, referral to an endodontist may be indicated.

Operative Procedures

Use of a rubber dam ( Fig. 19.4 ) during root canal treatment is usually indicated. However, when problems in locating pulp chambers are anticipated (e.g., tilted teeth, misoriented castings, or calcified chambers), initiating access without a rubber dam is preferred because it allows better crown-root alignment. When access is made without rubber dam placement, no intracanal instruments, such as files, reamers, or broaches, should be used unless they are secured by a piece of floss and a throat pack has been placed. Constricted chambers or canals must be sought patiently, with small amounts of dentin removed at a time.

Failure to recognize when the bur passes through the roof of the pulp chamber, if the chamber is calcified, may result in gouging or perforation of the furcation. As mentioned previously, after penetration of the roof of the chamber, use of a “safe-ended” access bur, such as the Endo Z (Dentsply/Maillefer, Tulsa, Oklahoma) or a pulp shaper bur (Dentsply/Tulsa Dental, Tulsa, Oklahoma), can prevent perforation of the chamber floor.

The use of electronic apex locators and angled radiographs is necessary for early perforation detection. Early detection reduces damage caused by continued treatment (irrigation, cleaning, and shaping) and improves the prognosis for nonsurgical repair.

Another useful method of providing isolation and also visualizing the crown-root alignment is the use of a “split” dam. This dam can be applied in the anterior region without a rubber dam clamp (see Chapter 15 ) or in posterior regions by quadrant isolation if a distal tooth can be clamped. Also, elimination of the metal clamp from the field of operation allows radiographic orientation of a coronal access preparation.

To orient the access, a bur may be placed in the preparation hole (secured with cotton pellets) and then radiographed ( Fig. 19.5 ). This provides information about the depth of access in relation to the canal’s location. Remember, a single canal is located in the center of the root. A direct facial radiograph shows the mesiodistal relationship; a mesial- or distal-angled film shows the faciolingual location. This procedure is helpful for locating small canals.

Use of a fiberoptic light during access preparation may assist in locating canals. This strong light illuminates the cavity when the beam is directed through the access opening (reflected light) and illuminates the pulp chamber floor (transmitted light). In the latter case, a canal orifice appears as a dark spot. Using magnifying glasses or an operative microscope also aids in locating a small orifice. Magnification loupes (2.5 or greater) are helpful, especially when used with transillumination. The ultimate aid in canal location is the operating microscope. Patients with problems requiring significant magnification for canal location should be referred to an endodontist who has this specialized equipment.

Recognition and Treatment

Perforation into the periodontal ligament (PDL) or bone usually (but not always) results in immediate and continuous hemorrhage. The canal or chamber is difficult to dry, and placement of a paper point or cotton pellet may increase or renew the bleeding. Bone is relatively avascular compared with soft tissue. Mechanical perforation may initially produce only hemorrhage equal to that of pulp tissue.

Perforations must be recognized early to avoid subsequent damage to the periodontal tissues with intracanal instruments and irrigants. Early signs of perforation may include one or more of the following: (1) sudden pain during the working length determination when local anesthesia was adequate during access preparation; (2) the sudden appearance of hemorrhage; (3) burning pain or a bad taste during irrigation with sodium hypochlorite; and (4) other signs, including a radiographically malpositioned file or a PDL reading from an apex locator that is short of the working length on an initial file entry.

Unusually severe postoperative pain may result from cleaning and shaping procedures performed through an undetected perforation. At a subsequent appointment the perforation site will be hemorrhagic because of inflammation of the surrounding tissues. The overall prognosis of the tooth must be evaluated with respect to the strategic value of the tooth, the location and size of the defect, and the potential for repair.

Perforation into the PDL at any location has a negative effect on the long-term prognosis. The dentist must inform the patient of the questionable prognosis and closely monitor the long-term periodontal response to any treatment. In addition, the patient must know what signs or symptoms indicate failure and, if failure occurs, what the subsequent treatment will be.

Perforations during access cavity preparation present a variety of problems. When a perforation occurs or is strongly suspected, the patient should be considered for referral to an endodontist. In general, a specialist is better equipped to manage these patients ( Fig. 19.6 ). Also, after long-term evaluation, other procedures, such as surgery, may be necessary if future failure occurs.

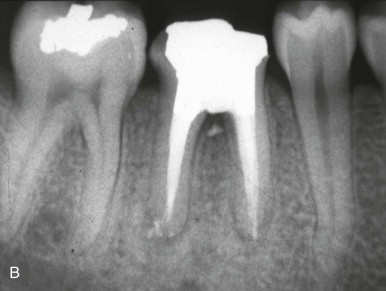

Lateral Root Perforation

The location and size of the perforation during access are important factors in a lateral perforation. If the defect is located at or above the height of crestal bone, the prognosis for perforation repair is favorable. These defects can be easily “exteriorized” and repaired with a standard restorative material, such as amalgam, glass ionomer, or composite. Periodontal curettage or a flap procedure is occasionally required to place, remove, or smooth excess repair material. In some cases, the best repair is placement of a full crown with the margin extended apically to cover the defect.

Teeth with perforations below the crestal bone in the coronal third of the root generally have the poorest prognosis. Attachment often recedes, and a periodontal pocket forms, with attachment loss extending apically to at least the depth of the defect. The treatment goal is to position the apical portion of the defect above the crestal bone. Orthodontic root extrusion is generally the procedure of choice for teeth in the esthetic zone. Surgical crown lengthening may be considered when the esthetic result will not be compromised or when adjacent teeth require surgical periodontal therapy. Internal repair of these perforations with mineral trioxide aggregate (MTA) has been shown to provide an excellent seal compared to other materials.

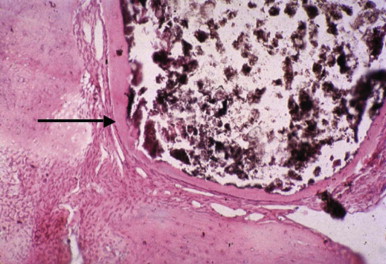

Furcation Perforation

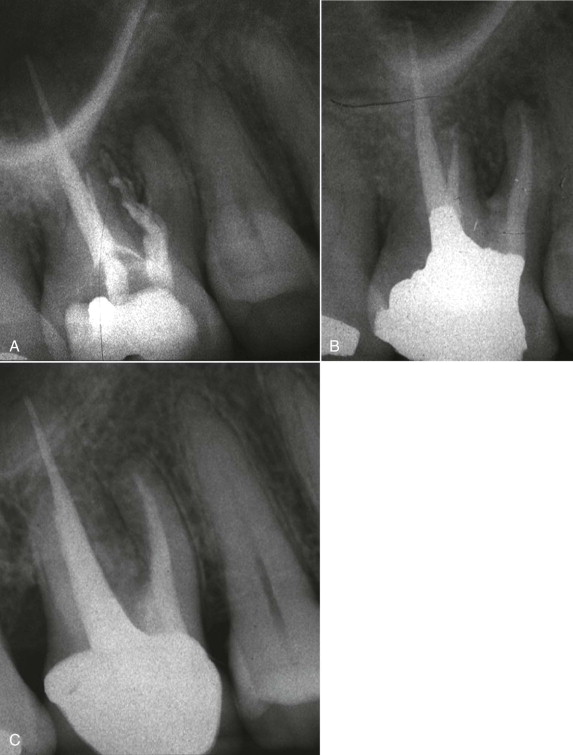

A perforation of the furcation is generally one of two types: the “direct” or the “stripping” type. Each is created and managed differently, and the prognoses vary. A direct perforation usually occurs during a search for a canal orifice. It is more of a “punched-out” defect into the furcation with a bur and is usually accessible, may be small, and may have walls. This type of perforation should be immediately (if possible) repaired with MTA ( Fig. 19.7 ). If proper conditions exist (dryness), glass ionomer or composite can be used to seal the defect. The prognosis is usually good if the defect is sealed immediately.

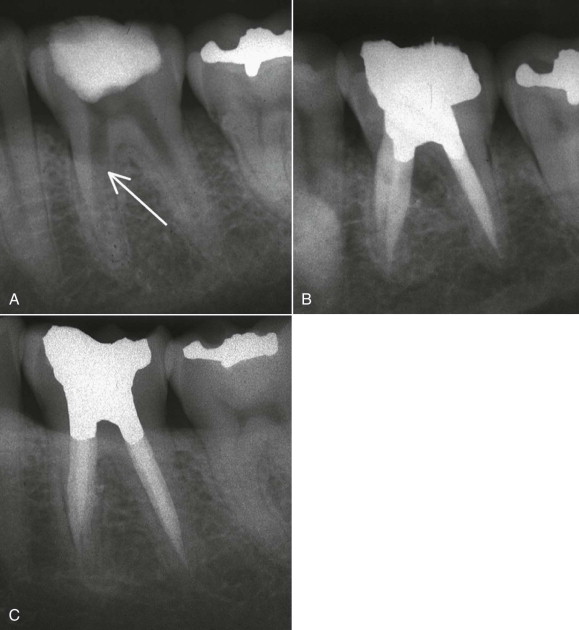

A stripping perforation involves the furcation side of the coronal root surface and results from excessive flaring with files or drills. Whereas direct perforations are usually accessible and therefore can be repaired nonsurgically, stripping perforations are generally inaccessible, requiring more elaborate approaches. The usual consequences of untreated stripping perforations are inflammation and subsequent development of a periodontal pocket. Long-term failure results from leakage of the repair material, which produces periodontal breakdown with attachment loss. Skillful use of MTA has significantly improved the prognosis of nonsurgical repair of stripping perforations compared with other repair materials ( Fig. 19.8 ).

Nonsurgical Treatment

If feasible, nonsurgical repair ( Fig. 19.9 ) of furcation perforations is preferred over surgical intervention. Traditionally, materials such as amalgam, gutta-percha, zinc oxide–eugenol, Cavit, calcium hydroxide, freeze-dried bone, and indium foil have been used clinically and experimentally to seal these defects. Repair is difficult because of potential problems with visibility, hemorrhage control, and management and sealing ability of the repair materials. In general, perforations occurring during access preparation should be sealed immediately, but the patency of the canals must be protected. Immediate repair of the perforations with MTA offers the best results for perforation repair.

Surgical Treatment

Surgery requires more complex restorative procedures and more demanding oral hygiene from the patient. Surgical alternatives include repair of the perforation with MTA if accessible by a surgical approach. If the perforation is not repairable or accessible by a surgical approach, hemisection, bicuspidization, root amputation, or intentional replantation should be considered. Teeth with divergent roots and bone levels that allow preparation of adequate crown margins are suitable for either hemisection or bicuspidization. Intentional replantation ( Fig. 19.10 ) is indicated when the defect is inaccessible or when multiple problems exist, such as a perforation combined with a separated instrument, or when the prognosis for other surgical procedures is poor. Dentist and patient must recognize that the prognosis for treatment of surgically altered teeth is guarded because of the increased technical difficulty associated with restorative procedures and the demanding oral hygiene requirements. The remaining roots are prone to caries, periodontal disease, and vertical root fracture. Treatment planning options, including extraction, should be discussed with the patient when the prognosis is poor.

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses