Despite vast improvements in the oral health status of the United States population over the past 50 years, disparities in oral health status continue, with certain segments of the population carrying a disproportionate disease burden. This article attempts to describe the problem, discuss various frameworks for action, illustrate some solutions developed by the private sector, and present a vision for collaborative action to improve the health of the nation. No one sector of the health care system can resolve the problem. The private sector, the public sector, and the not-for-profit community must collaborate to improve the oral health of the nation.

Despite vast improvements in the oral health status of the United States population over the past 50 years, disparities in oral health status continue, with certain segments of the population carrying a disproportionate disease burden. In the landmark Surgeon General’s report, Oral Health in America , dental caries is identified as the most common chronic disease of childhood—five times more common than asthma, with low-income children experiencing twice as much disease as affluent children. Although the reasons for these disparities vary, a principle contributing factor remains limited access to care for certain populations.

Multiple factors are responsible for this limited access, and there is confusion as to what is meant by “access to care.” Some have defined access in the broadest possible sense as “peoples’ ability to receive the oral health care that they desire.” Others cite economic theory and the behavior of markets to describe access challenges, focusing on either supply or demand within the oral health care system. The main criterion for evaluating access to care has been the percentage of members of various groups that has had a dental visit during a referenced time period. Although this percentage is an inadequate way to measure the total experience with care, it does indicate entry into the system. A measure of the adequacy of access to care for underserved groups should be that they attain the same level of access enjoyed by the general population.

This article attempts to describe the problem, discuss various frameworks for action, illustrate some solutions developed by the private sector, and present a vision for collaborative action to improve the health of the nation. No one sector of the health care system can resolve the problem. The private sector, the public sector, and the not-for-profit community must collaborate to improve the oral health of the nation.

Nature of the problem

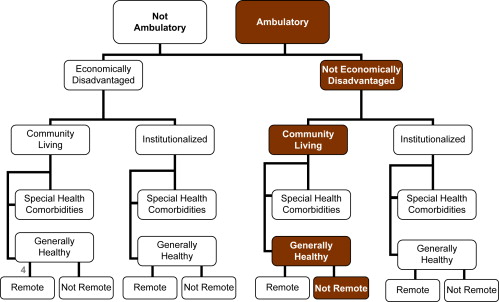

Any analysis of access to oral health care requires identification of those groups potentially or actually experiencing inadequate access and the contributing factors. Fig. 1 , a schematic diagram that segments the United States population into groups, is useful in understanding the major barriers to access. Although quantification of the size of the population in each group is not given in this diagram, some estimates are available: the institutionalized population is 1.4% of the general population; those with severe medical comorbidities make up 8.7% of the population; the economically disadvantaged include 15.3% of Americans; and 1.1% of the population lives in remote areas.

Data quoted in the Workforce Taskforce Report (American Dental Association, unpublished data, October 2000) based upon National Health Interview Surveys (NHIS) conducted by the National Center for Health Statistics (NCHS), show that 63.6% of those interviewed had a dental visit in 2006. These persons are ambulatory, live in community settings that are not remote, are generally healthy, and have adequate financial resources to access care. They are represented by the shaded boxes in the diagram. The unshaded boxes, representing a minority of Americans, indicate the various groups within the population whose members exhibit some characteristic that potentially predisposes them to encounter access barriers. The number of differing population segments makes clear that no one solution to the problem will be successful for all, even though some groups face similar problems. Still, specific elements in targeted solutions may be effective with multiple groups.

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses