Learning Objectives

After reading this chapter, the student should be able to:

- 1.

Describe the main factors involved in the survival of root-filled teeth.

- 2.

Summarize factors contributing to loss of tooth strength and describe the structural importance of remaining tooth tissue.

- 3.

Explain the importance of a coronal seal and how it is achieved.

- 4.

Describe the requirements of an adequate restoration.

- 5.

Outline postoperative risks to the unrestored tooth.

- 6.

Discuss the rationale for immediate restoration.

- 7.

Identify restorative options before root canal treatment is started.

- 8.

Discuss the advantages and disadvantages of direct and indirect restorations.

- 9.

Outline indications for post placement in anterior and posterior teeth.

- 10.

Describe common post systems and the advantages and disadvantages of each.

- 11.

Describe core materials and their placement.

- 12.

Describe techniques for restoring an access opening through an existing restoration.

Prompt restoration is required to minimize the risk of tooth fracture and coronal leakage. Restorability should be confirmed before root canal treatment begins. All caries and any existing restorations should be removed, both to reduce the risk of marginal leakage during treatment and to reveal the extent of residual tooth structure. Options for restoration, based on the amount of remaining tooth structure and functional demands, are also considered at this stage. In most cases, restoration is straightforward, but the choice must be based on sound principles if the tooth is to be retained long term as a functional unit. This chapter considers principles of restoration rather than detailed techniques, which are beyond the scope of this textbook.

Learning Objectives

After reading this chapter, the student should be able to:

- 1.

Describe the main factors involved in the survival of root-filled teeth.

- 2.

Summarize factors contributing to loss of tooth strength and describe the structural importance of remaining tooth tissue.

- 3.

Explain the importance of a coronal seal and how it is achieved.

- 4.

Describe the requirements of an adequate restoration.

- 5.

Outline postoperative risks to the unrestored tooth.

- 6.

Discuss the rationale for immediate restoration.

- 7.

Identify restorative options before root canal treatment is started.

- 8.

Discuss the advantages and disadvantages of direct and indirect restorations.

- 9.

Outline indications for post placement in anterior and posterior teeth.

- 10.

Describe common post systems and the advantages and disadvantages of each.

- 11.

Describe core materials and their placement.

- 12.

Describe techniques for restoring an access opening through an existing restoration.

Prompt restoration is required to minimize the risk of tooth fracture and coronal leakage. Restorability should be confirmed before root canal treatment begins. All caries and any existing restorations should be removed, both to reduce the risk of marginal leakage during treatment and to reveal the extent of residual tooth structure. Options for restoration, based on the amount of remaining tooth structure and functional demands, are also considered at this stage. In most cases, restoration is straightforward, but the choice must be based on sound principles if the tooth is to be retained long term as a functional unit. This chapter considers principles of restoration rather than detailed techniques, which are beyond the scope of this textbook.

Risks to Survival of Root-Filled Teeth

Although root-filled teeth are at greater risk of extraction than vital teeth, their long-term survival rate is very high. Numerous studies investigating the survival of root-filled teeth have documented that at most 1% to 2% are lost per year, and one very large study of almost 1.5 million cases reported that only 2.9% of teeth were lost after 8 years. A recent meta-analysis showed a mean survival of 87% after 8 to 10 years. The restoration is the key to survival.

The major risks to root filled teeth are as follows:

- 1.

Caries and periodontal disease. Caries and periodontal disease are responsible for up to half of all extractions of root-filled teeth. Emerging evidence suggests that root-filled teeth may be more susceptible to caries than vital teeth, though the biologic reasons for increased susceptibility are unknown.

- 2.

Lack of definitive restoration. A surprisingly high percentage of teeth are not appropriately restored after root canal treatment. In one study of U.S. insurance data, almost 30% of teeth had not been restored 2 years after root canal treatment, and 11% of these teeth were extracted.

- 3.

Inadequate restoration. Lack of coronal coverage is the major restorative factor in tooth loss after root canal treatment. Of the extracted teeth in the study mentioned previously involving 1.5 million teeth, 85% did not have coronal coverage. The lack of cuspal protection predisposes the tooth to unrestorable cusp or crown fracture. Direct restoration does not provide adequate protection unless the access opening is confined to the occlusal surface.

- 4.

Occlusal stresses. Teeth serving as abutments for fixed or removable prostheses are at significantly increased risk of loss, as are teeth lacking mesial and distal proximal support from adjacent teeth.

- 5.

Endodontic factors. Typically only about 10% of extractions result from an endodontic cause, including persistent pain. Endodontic problems (development or persistence of a periapical lesion) are generally amenable to further management rather than extraction. Procedural problems (e.g., perforations) may also lead to extraction.

Structural and Esthetic Considerations

Teeth function in a challenging environment, with heavy occlusal forces and repeated loading at a frequency of more than 1 million cycles per year over many decades of clinical life. Caries, restorative procedures, and occlusal stresses add to the risk of serious damage to teeth during normal function, and root-filled teeth are at greater risk than intact teeth. As noted previously, unrestorable crown fracture is a common sequel to inadequately protected root-filled teeth ( Fig. 17.1 ). It is important to understand the basis for this fracture susceptibility when planning the restoration.

Structural Changes in Dentin

It is now generally recognized that many mechanical properties of the dentin of root-filled teeth differ only to a minor extent from those of the dentin of vital teeth (strength, hardness, modulus of elasticity). Similarly, the moisture content of dentin is unaffected by loss of pulp vitality. Despite the seemingly minor differences, other biomechanical factors may result in substantial differences between vital and root-filled teeth. The fracture toughness of dentin is probably a very important property in relation to fracture susceptibility, but it has not been widely investigated in relation to the dentin of the root-filled tooth. The loss of dentinal fluid, which may play a role in stress distribution and stress relief, could also contribute to changes in the response of root-filled teeth to occlusal stresses.

Loss of Tooth Structure

Most teeth requiring root canal treatment are already structurally compromised by caries and subsequent restorative procedures. Every step of root canal treatment and restoration removes additional dentin. Teeth are measurably weakened even by occlusal cavity preparation; greater loss of tooth structure further compromises strength. Loss of one or both marginal ridges is the major contributor to reduced cuspal stiffness (strength) ( Fig. 17.2 ). Endodontic access has only a minor effect on decreasing cuspal strength when the access cavity is surrounded by solid walls of dentin. In a tooth already seriously compromised by caries, trauma, or large restorations, the access cavity is more significant, particularly if the adjacent marginal ridges have been lost. Excessive coronal flaring also results in greater susceptibility to cusp fractures.

Biomechanical Factors

The occlusal loads to which teeth are subjected during normal function generate large stresses in teeth that are capable of causing cusp fracture and even vertical root fracture in intact vital teeth. Cuspal flexure (movement under loading) weakens the premolars and molars over time. As cavity preparations become larger and deeper, unsupported cusps become weaker and show more deflection under occlusal loads. Greater cuspal flexure leads to cyclic opening of the margins between the tooth and the restorative material. The alteration of the internal canal morphology resulting from endodontic and restorative procedures may also contribute to loss of rigidity. The distribution of stresses in the restored root-filled tooth subjected to occlusal load is markedly changed from those in the intact, vital tooth. Fatigue is also a factor; cusps become progressively weaker with repetitive flexing. Hence, the restoration must be designed to minimize cuspal flexure to protect against fracture and marginal leakage.

Esthetic Factors

Increasingly, patients wish to enhance the esthetic appearance of restorations, and for root-filled teeth this often involves metal-ceramic or all-ceramic crowns. It is necessary to allow adequate thickness of the ceramic to provide a more natural appearance. Removal of tooth structure during preparation for metal-ceramic and all-ceramic crowns is greater than for a cusp overlay cast restoration or an all-metal crown. Residual coronal tooth structure may be further weakened as a result.

Requirements for an Adequate Restoration

Based on the concepts discussed, the definitive restoration should (1) preserve remaining tooth structure, although not at the expense of appropriate restoration; (2) protect remaining tooth structure and in particular minimize cuspal flexure; (3) provide a coronal seal; and (4) satisfy function and esthetics. Care must be taken to ensure that esthetic demands do not lead to the weakening of teeth by excessive removal of remaining tooth structure.

Coronal Seal

Coronal leakage is a major cause of endodontic failure. Even a well-obturated canal does not provide an enduring barrier to bacterial penetration, and we rely on the restoration for long-term integrity of the coronal seal. The restoration may provide the coronal seal either as a separate step (e.g., placing a barrier over canal orifices) or, more commonly, as an integral part of the restoration. For direct restoration of a simple access cavity, a bonded restoration provides the most reliable seal. Experimental leakage studies consistently demonstrate that leakage occurs around a post, regardless of the type of post or luting cement. However, a crown with an adequate ferrule, plus a post and core foundation, provides an effective barrier against coronal leakage.

A frequently asked question with regard to lost or leaking restorations is, “How long can a root filling be exposed to oral fluids before it should be retreated?” The question has no clear answer. Experimental studies suggest that complete leakage along the length of the root filling occurs rapidly, within days or weeks. A recent review, however, concluded that coronal leakage may be clinically less significant than is suggested by experimental laboratory leakage studies. Clinically, periapical lesions may not develop even several years after the coronal seal is lost, and bacterial invasion is often limited to the coronal third of the canal. The commonly accepted guideline is that the root filling should be replaced if it is exposed to oral fluids for more than 2 to 3 months. However, if the root filling has been performed to a high technical standard and periapical pathology is absent, it may be sufficient to replace the lost or leaking restoration rather than the entire root filling.

Restoration Timing

Unless there are specific reasons for delay, definitive restoration is completed as soon as practical. Most provisional restorative materials used to seal the endodontic access opening have low wear and fracture resistance; substantial occlusal wear and loss of the coronal seal may occur within weeks. The tooth is at its weakest after access and remains so until it has been appropriately restored. The provisional restoration does not provide complete protection against occlusal forces, even when the tooth is out of occlusion. Unrestorable fracture during or soon after treatment is all too common ( Fig. 17.3 ). Protection can be provided in the form of an orthodontic band cemented around the tooth.

For most teeth, it is unnecessary to wait for radiographic evidence of healing before the definitive restoration is placed. Prompt restoration may improve the prognosis because it provides better protection against fracture and loss of the coronal seal. With a guarded prognosis, the rationale for postponing definitive restoration is based on the nature of further management if failure occurs. Orthograde retreatment is usually possible through the restoration (addressed later in this chapter) unless a post is placed in the canal. If correction requires surgery, there is no reason to delay restoration. The only reason for delay is a questionable prognosis, as when failure would lead to extraction.

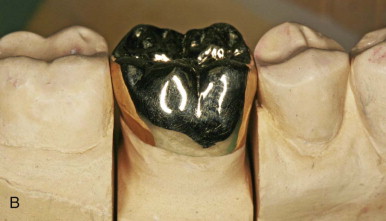

When definitive restoration of the tooth is delayed, the provisional restoration must be durable and must protect, seal, and meet functional and esthetic demands. Provisional materials such as Cavit are inadequate. For posterior teeth, some form of cuspal protection is desirable, even with provisional restorations. A good long-term posterior provisional restoration is an amalgam core that covers weakened cusps, thus providing functional and sealing protection. The definitive crown preparation can be completed later without removing the core ( Fig. 17.4 ). Comparable anterior restorations are more challenging owing to esthetic demands and difficulties with the coronal seal. A one-piece provisional post-crown is at risk of dislodgment, thereby compromising an adequate seal. It is preferable to place a definitive post and core immediately when a provisional crown is indicated.

Restoration Design

Principles and Concepts

Three practical principles are important in ensuring function and durability.

- 1.

Conservation of tooth structure. Some anterior root canal–treated teeth are intact or minimally restored, and there is evidence supporting restoration of only the coronal access opening rather than a crown or a crown combined with a post and core, requiring little if any additional tooth structure removal. Some data even indicate that molars that are intact (except for small endodontic access openings) can be restored using only composite resin. However, most root canal–treated posterior teeth and some anterior teeth are structurally compromised, and crown placement is required so that the cusps and remaining tooth structure can be encompassed, which minimizes the potential for tooth fracture and enhances tooth longevity. The process used by some practitioners of routinely decoronating an endodontically treated tooth and then rebuilding it is neither desirable nor in keeping with contemporary science.

- 2.

Retention. The definitive coronal restoration of a root canal–treated tooth may consist only of a restoration filling the endodontic access opening that is retained by surrounding tooth structure. When the tooth is structurally compromised and a crown is needed, it is retained by remaining dentin and a restorative material core that replaces missing tooth structure. If the core cannot be adequately retained by the remaining coronal tooth structure, a post can be placed into the pulp chamber and root canal to provide retention for the core. Because posts weaken teeth and may produce root fracture or lead to root perforation during preparation of the root canal, they should be used only when the core cannot be retained by some other means, such as mechanical and chemical bonding of a restorative material.

- 3.

Protection of remaining tooth structure. In posterior teeth, this applies to protecting weakened cusps by minimizing their flexure and fracture. The restoration is designed to encompass the cusps and minimize the chance of tooth fracture and also to transmit functional loads through the tooth to the suspensory apparatus.

Planning the Definitive Restoration

The choice of definitive restoration is straightforward when the root canal–treated tooth is intact or only minimally restored with an appropriate restoration. The preferred treatment is removal of the provisional restoration in the endodontic access opening and also any other material (e.g., cotton pellets). The root canal filling material should be visible; amalgam or composite resin then is used to restore the area, depending on esthetic requirements.

When the tooth requires a crown, the type of definitive treatment can be determined only after the existing restoration (or restorations) have been removed, to ensure that there is no caries present and to expose the remaining sound tooth structure. Visualizing the restorative preparation in advance ensures that structural requirements for retention of the core are preserved. Increasingly, esthetic demands dictate the use of all-ceramic or metal-ceramic crowns for definitive tooth restoration. These materials usually function satisfactorily, but they have less favorable physical properties than all-metal restorations, particularly in mouths where occlusal forces are heavy, as evidenced by wear facets and parafunctional habits such as bruxism.

Anterior Teeth

Whenever possible, direct restoration of the endodontic access opening (e.g., etched and bonded composite resin) is used; this is sufficient for teeth that are otherwise largely intact. For more extensively damaged anterior teeth (trauma, large proximal restorations), complete coronal coverage using a metal-ceramic or all-ceramic crown supported by a post and core is indicated. The choices for premolars and molars are more varied.

Posterior Teeth

Direct Restorations

Restorations placed directly into the endodontic access opening (amalgam or composite resin) are conservative, but their use must be carefully considered. The restoration must protect against coronal fracture. Indications for restoration of only the coronal access opening include the following:

- 1.

Minimal tooth structure is lost before and during root canal treatment; a conservative access preparation is present with intact marginal ridges, and the tooth can be restored without further preparation.

- 2.

The long-term prognosis of the tooth is uncertain, but a durable restoration is needed during the observation period.

Posterior teeth with substantial tooth structure loss may be restored with amalgam if it is esthetically acceptable and if unsupported cusps are adequately protected by the amalgam. Some cuspal coverage amalgams have lasted for many years ( Fig. 17.5 ), whereas others have fractured due to the presence of heavy occlusal forces. Assessment of occlusal forces and functional activity helps determine whether a cuspal coverage amalgam is a suitable restoration. A conventional Class II amalgam without cuspal coverage does not provide cuspal protection and ordinarily should not be used. At a minimum, cusps adjacent to a lost marginal ridge should be onlayed with sufficient thickness of amalgam (at least 2 mm) to resist occlusal forces ( Fig. 17.5 ). The amalgam should extend into the pulp chamber and canal orifices to aid retention. The amalgam may subsequently serve as a core for an indirect cast restoration if indicated ( Fig. 17.6 ). Bonded amalgams have also been used, but their clinical performance in root-filled teeth has not been well documented, and bond failure is likely to be catastrophic in the presence of weakened, unprotected cusps.

There are esthetic deficits when amalgam is used in visible teeth, and the need for a tooth-colored restoration warrants the use of bonded composite resin restorations. The use of bonding continues to escalate as materials and techniques improve, and good results have been reported in a long-term prospective clinical study of composite resin restorations. Proximal leakage and recurrent proximal caries remains a concern, particularly when the restorations have subgingival margins and were placed without the use of a rubber dam.

Indirect Restorations

All-metal cast restorations (onlays and three-quarter and complete crowns) provide excellent occlusal protection and are optimal when the loss of tooth structure requires a crown. The attractiveness of onlays is that the tooth preparation design is more conservative than complete coverage preparations, yet provides good cuspal coverage ( Fig. 17.7 ). The strength of gold allows conservative tooth reduction, with a reverse bevel providing effective cuspal coverage. Complete coverage all-metal crowns are used when there is insufficient coronal tooth structure present for a more conservative restoration or if functional or parafunctional stresses require the protective effect of complete coronal coverage.

When a tooth is prepared for a crown, the coronal access opening should be restored and sealed with an amalgam or a bonded composite resin as part of the core foundation for the crown. Glass ionomer can also be used to restore the access opening, as long as its purpose is to seal the opening and it is not forming a substantial portion of the axial walls that will be used for retention of the crown.

The esthetic requirements of many patients prevent the use of all-metal crowns. Metal-ceramic or all-ceramic crowns have become the most frequently used materials for root canal–treated posterior teeth. These types of complete crowns provide a reliable, strong restoration that protects against root fracture ( Fig. 17.8 ). However, root canal treatment may have required substantial tooth structure removal and that, coupled with the reduction needed for a crown, can necessitate placement of a core restoration and sometimes a post to retain the core. To plan the core shape there must be complete exposure of the tooth’s perimeter. Gingival retraction cord and sometimes soft tissue removal via electrosurgery or use of a laser are beneficial methods that help prevent undersized cores being made because of incomplete viewing of the finish line. When a core is used as a foundation for the crown without the use of a post, the material must be well retained into remaining tooth structure and must be of sufficient thickness so that the material will not fracture during function, resulting in crown failure ( Fig. 17.9 ).

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses