Introduction

Orthodontic space opening during adolescence is a common treatment for congenitally missing maxillary lateral incisors. Because of continued facial growth and compensatory tooth eruption, several years can elapse between completion of orthodontic treatment for a teenage patient and implant placement. There are reports that, after successful orthodontic opening of the implant space, the central incisor and canine roots reapproximate during retention and prevent implant placement.

Methods

To study this phenomenon, the records of 94 patients with missing maxillary lateral incisors were collected. Periapical and panoramic radiographs were used to measure intercoronal and interradicular distances between the central incisor and the canine adjacent to the missing lateral incisor before and after orthodontic treatment and at implant placement.

Results

Although root approximation between the adjacent central incisor and canine during retention did not occur consistently, 11% of the patients experienced relapse significant enough to prevent implant placement.

Conclusions

To ensure sufficient space for implant placement, we recommend at least 6.3 mm of intercoronal space and 5.7 mm of interradicular space between the adjacent central incisor and canine. A bonded wire or resin-bonded bridge will help to reduce root approximation that might occur during retention.

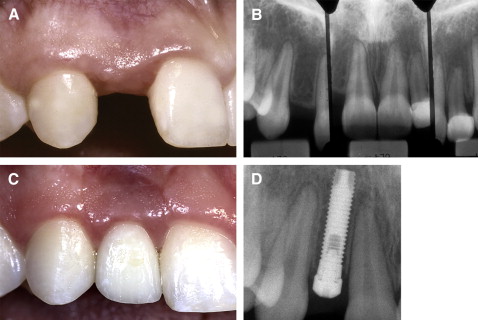

Orthodontic space opening during adolescence is a common treatment for congenitally missing maxillary lateral incisors. In these situations, implants are often used to replace the missing tooth to establish ideal esthetics without restoring the adjacent teeth ( Fig 1 ).

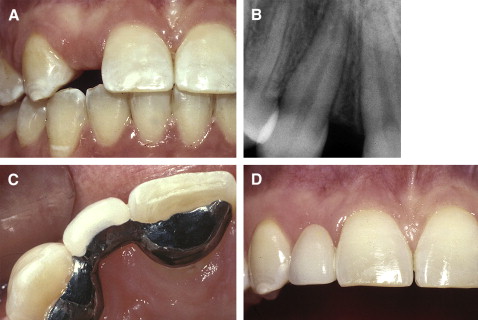

However, several years can elapse between completion of orthodontic treatment for a teenage patient and implant placement because of continued facial growth and compensatory tooth eruption. Since the implant cannot erupt, if it is placed too early, it will appear to submerge vertically as the adjacent teeth continue to erupt. It is therefore not uncommon to wait 3 to 5 years after orthodontic treatment before placing a lateral incisor implant. What happens to the positions of the maxillary canine and the central incisor roots during that time? Dickinson reported that, after successful orthodontic opening of the implant space, the central incisor and canine roots reapproximated during retention and prevented implant placement. This problem is frustrating for both the orthodontist and the patient and could require either orthodontic retreatment to facilitate implant placement or the placement of a fixed prosthesis ( Fig 2 ). The literature addressing these issues is limited. To date, no studies have looked at what happens to the space created between maxillary central incisor and canine crowns and roots after orthodontic appliance removal. Seen clinically, do the roots of these teeth exhibit movement or angulation changes into the implant space sufficient to prevent implant placement? The purpose of this study was to evaluate postorthodontic root approximation adjacent to congenitally missing maxillary lateral incisors during retention.

Material and methods

Records of 94 patients were collected from various orthodontic, periodontal, and oral surgery practices according to the following criteria: (1) congenitally missing at least 1 maxillary lateral incisor, (2) treated orthodontically to open space for a lateral incisor restoration, (3) not missing an adjacent central incisor or canine, (4) no significant root resorption on the adjacent central incisor or canine, and (5) treatment completed between 1990 and 2008.

These 94 subjects had 142 missing lateral incisors. Of them, 80 patients (121 missing lateral incisors) were consecutively treated in 1 periodontal practice. Although all available radiographs were collected, unfortunately, not all patients had a complete set of radiographs at all 3 time points.

Periapical and panoramic radiographs were collected and used to measure the distance between the central incisor and canine adjacent to the missing lateral incisor. Periapical radiographs were taken with the parallel technique, which reduces some potential errors inherent in a radiographic study when compared with other radiographic techniques. Because the entire consecutive sample was taken from 1 periodontal practice, we were confident that the measurements could be readily compared between patients. The radiographs were scanned, imported, and analyzed with Scion Image, a public domain Java image-processing program developed at the US National Institutes of Health and available on the Internet at http://www.scioncorp.com/pages/scion_image_windows.htm . All measurements were made to the nearest 0.01 mm. Corrections for radiographic magnification at different time points and between different types of radiographs were made by comparing the mesiodistal width of a reference tooth (the adjacent canine) measured at the cementoenamel junction (CEJ). The following time points were used: T1, before orthodontic treatment; T2, after orthodontic treatment; and T3, before implant placement.

One examiner (T.M.O.) evaluated the space between the central incisor and the canine at each time point. The following measurements were made.

- 1.

Intercoronal distance: the distance between the adjacent central incisor and canine crowns, measured at the CEJ.

- 2.

Interradicular distance: the distance between the adjacent central incisor and canine roots at their nearest proximity.

- 3.

Reference: the mesiodistal width of the adjacent canine measured at the CEJ.

The interradicular measurements were made at the point of closest proximity between the adjacent central incisor and canine roots. This measurement was made from the corresponding adjacent lamina dura to minimize any changes from root resorption. To ensure examiner reliability, the primary author (T.M.O.) repeated and recorded complete T2 and T3 measurements for 10 randomly selected patients 1 month after the T1 measurements.

Statistical analysis

The intercoronal and interradicular distances were measured at T1, T2, and T3 on both the panoramic and periapical radiographs. We compared the intercoronal and interradicular measurements at T2 and T3 using a paired t test. The 95% CI was calculated when assessing the incidence of dental movement significant enough to prevent implant placement. Because some patients were missing both lateral incisors, these teeth could not be considered independent. Generalized estimating equations were used to account for this lack of independence when calculating the 95% CI for overall missing lateral incisors. The sample was divided into 2 groups for further analysis.

In the adequate space group, intercoronal and interradicular distances at T3 were judged by the surgeon to be sufficient for placing a dental implant.

In the inadequate space group, intercoronal or interradicular distances at T3 were judged by the surgeon to be insufficient for placing a dental implant.

Intercoronal and interradicular distance changes in the adequate space vs the inadequate space groups were compared by averaging the measurement changes in all patients between T2 and T3. We compared the measurement changes in each group, as well as differences based on age at T2 and sex, using independent sample t tests. Fisher exact tests were used to assess the association between implant placement success and the method of retention. All analyses were performed with SPSS software (version 16.0, SPSS, Chicago, Ill) with a significance level of 0.05.

The examiner’s reliability was assessed by computing intraclass correlation coefficients (Pearson’s r) for repeated measurements. These measurements were highly repeatable, with coefficients of 0.97 and 0.98 for the intercoronal and interradicular measurements, respectively. Furthermore, the mean errors for intercoronal and interradicular measurements computed with Dahlberg’s formula were 0.10 and 0.11 mm, respectively. The standard errors of the mean difference of repeated measurements were 0.04 and 0.05 mm, respectively.

Results

Many orthodontists use panoramic radiographs to assess root proximity and end-of-treatment results. In part because of reported distortion in panoramic radiographs, many surgeons use periapical radiographs to measure the distance between roots. To elucidate potential differences between these 2 types of radiographs, we compared the distances measured on both the periapical and panoramic radiographs that were taken on the same day—intercoronal and interradicular distances between the central incisor and the canine, and mesiodistal width of the reference tooth (canine) measured at the CEJ. We then assessed the magnification of these 57 pairs of panoramic and periapical radiographs. The mean ratios of the intercoronal, interradicular, and reference teeth were 1.12, 1.21, and 1.08, respectively ( Table I ). This variation in magnification between 8% and 21% at different locations on the radiographs shows the distortions in panoramic radiographs.

| Intercoronal | Interradicular | Reference | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mean ratio | 1.12 | 1.21 | 1.08 |

| SD | .11 | .12 | .09 |

| Range | .85-1.40 | .92-1.51 | .9-1.32 |

At T3, the surgeon’s assessment for fixture placement was based primarily on the space available between the CEJ and the roots of the adjacent teeth and on the size of the implant. At this assessment, 16 patients (with 25 missing lateral incisors) of the total sample of 94 patients (with 142 missing lateral incisors) had inadequate space between the central incisor and the canine to permit implant placement. These patients composed the inadequate space group ( Table II ).

| Patients | Missing lateral incisors | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | n | % | |

| Adequate space | 78 | 83.0 | 117 | 82.4 |

| Inadequate space | 16 | 17.0 | 25 | 17.6 |

| Total (n) | 94 | 142 | ||

To establish the incidence of postorthodontic dental movement sufficient to prevent implant placement, we evaluated 80 patients (with 121 missing lateral incisors) who were treated consecutively in 1 periodontal office. Of this sample, 9 patients had inadequate space for an implant at T3. They were missing a total of 14 lateral incisors of a possible 121. That is, 11.3% of the patients (95% CI, 4.3%-18.2%) and 11.6% of the missing lateral incisors (95% CI, 5.9%-21.3%) had enough change in root angulation of the adjacent teeth to prevent implant placement ( Table III ).

| Patients | Missing lateral incisors | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | n | % | |

| Adequate space | 71 | 88.8 | 107 | 88.4 |

| Inadequate space | 9 | 11.3 | 14 | 11.6 |

| Total (n) | 80 | 121 | ||

Of the total sample, 42 patients (with 63 missing laterals) had periapical radiographs available at T2 and T3. This sample had a mean of 14 months between T2 and T3 (range, 1-58 months). Patients with only a short time between T2 and T3 were included because some had sufficient root movement to inhibit implant placement in only 2 months. Practicing orthodontists will attest that when retainers are not worn, relapse can occur quickly; practitioners should be aware that root movement and clinical crown movement can occur rapidly. It would be wise to consider this when determining the timing of orthodontic treatment and implant placement.

To assess dental movement during the retention period, the changes in intercoronal and interradicular distances between the adjacent central incisor and the canine were analyzed. Each measurement was scaled to the overall average magnification (1.02 times), determined by comparing the reference canine measurements at T2 and T3. Although an average magnification does not rule out possible individual magnification error, it levels the field statistically and allows for proper statistical analysis. Overall, the intercoronal distance changed an average of 0.09 mm (95% CI, –0.04-0.22). The interradicular distance changed an average of –0.04 mm (95% CI, –0.17-0.10). Neither change was statistically significant (intercoronal: P = 0.17; interradicular: P = 0.60) ( Table IV ). Positive change indicates an increase in distance, and negative change indicates a decrease in distance.

| Intercoronal | Interradicular | |

|---|---|---|

| Mean | 0.09 mm | −0.04 mm |

| SD | 0.51 mm | 0.52 mm |

| 95% CI | −0.04-0.22 | −0.17-0.10 |

| P value | 0.17 | 0.60 |

The average interdental changes indicate that, in this sample, the adjacent central incisor and canine crowns or roots did not reapproximate during retention; ie, angulation changes during retention is not a universal phenomenon.

We analyzed the adequate space and inadequate space groups to elucidate factors that affected the maintenance of adequate space for implant placement.

At T2, the average intercoronal space between the central incisor and the canine in the adequate space group was 6.31 mm (95% CI, 6.17-6.46; range 5.25-7.56). The average interradicular space between these teeth was 5.74 mm (95% CI, 5.56-5.93; range, 4.06-7.12) ( Table V ).

| T2 | T3 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intercoronal | Interradicular | Intercoronal | Interradicular | |

| Adequate space | 6.31 mm | 5.74 mm | 6.33 mm ∗ | 5.62 mm ∗ |

| Inadequate space | 6.23 mm | 4.97 mm | 5.53 mm ∗ | 3.94 mm ∗ |

| P value of difference | 0.65 | 0.012 | 0.014 | 0.0003 |

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses