Dental distraction is an orthodontic tooth movement technique that allows closure of extraction spaces, usually of premolars, in periods from 1 to 3 weeks, by bodily retraction of the canine. This article reports on canine distalization by using a distractor device obtained from a conventional hyrax screw. The patient was an adolescent boy, aged 17 years 9 months, who came to the clinic with the chief complaint of tooth crowding. The clinical examination showed a convex profile, retroclined and protruded maxillary incisors, buccally tipped and protruded mandibular incisors, and a Class I malocclusion. The treatment comprised extractions and rapid canine distraction procedures. Pretreatment, posttreatment, and 2-year follow-up records are shown and demonstrate that dental distraction is a viable alternative of treatment. With this treatment strategy, satisfactory results were obtained without additional anchorage devices, achieving an attractive smile and optimal occlusion. The main considerations about the treatment alternatives and their clinical concerns are discussed.

Most orthodontic patients have some shortage of space or crowding. Although nonextraction treatment has become popular during the last decade, in these patients, extractions are often needed for a favorable treatment outcome. In many patients, the orthodontic treatment period with extractions is prolonged because of the limited rate of biologic tooth movement, and the long duration of treatment is a chief complaint of these patients.

The first stage of treatment for patients needing premolar extractions is distal movement of the canines. Liou and Huang introduced the technique of rapid canine retraction to shorten the orthodontic treatment time and named it dental distraction . Rapid orthodontic tooth movement is a form of distraction osteogenesis by distracting the periodontal ligament, similar to osteogenesis in the midpalatal suture during rapid maxillary expansion. Currently, canine distractors are bulky, unidirectional, and unavailable on the market. They must be refined, developed, and oriented with fixed appliances. Additionally, the long-term effects of periodontal distraction should be further evaluated. Considering all these aspects, in this report, we present the modifications and results obtained by dental distraction, with a 2-year follow-up, using a distractor obtained from a conventional hyrax screw.

Diagnosis and etiology

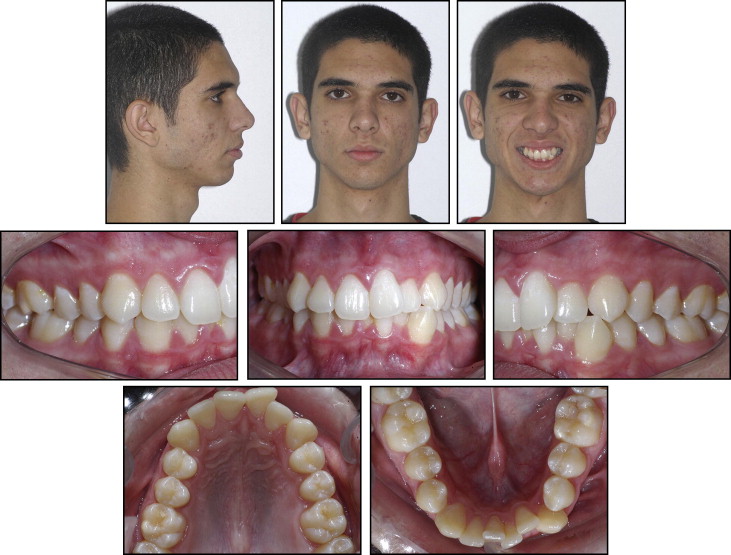

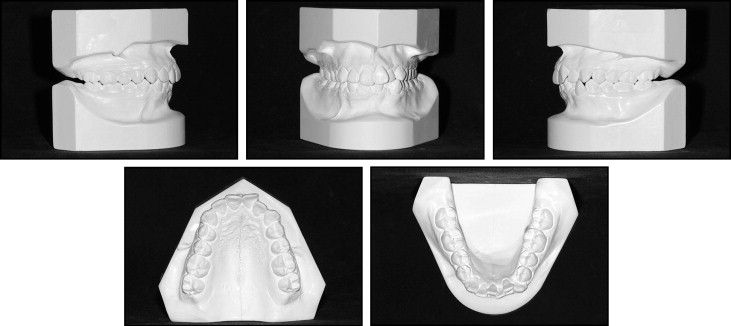

A male patient, aged 17 years 9 months, with a Class I malocclusion, came for orthodontic treatment with the chief complaint of “crooked teeth.” The facial photographs ( Fig 1 ) showed proportional facial thirds and a convex profile. The intraoral photographs and dental casts ( Figs 1 and 2 ) show an overjet of 3 mm, an overbite of 50%, negative tooth-size discrepancies of 5.5 mm in the maxillary arch and 8 mm in the mandibular arch, and deviation of the mandibular midline of 1.5 mm to the left side. The cephalogram and its tracing ( Table ; Fig 3 , A and B ) show the skeletal Class I pattern with an ANB angle of 4°. The maxillary incisors were retroclined and protruded; the mandibular incisors were buccally tipped and protruded (1-NA, 7 mm; 1:NA, 19°; 1-NB, 8 mm; 1:NB, 33°; and IMPA, 97°). The patient exhibited a slightly reduced mandibular length and crowding in both dental arches (Co-Gn, 115 mm, Pog-NPerp, −13 mm). Considering the values of the occlusal plane angle (Ocl:SN, 19°), mandibular plane (GoGn:SN, 37°), and y-axis (y-axis to Frankfort horizontal, 61°), a predominantly vertical growth pattern was inferred. The panoramic radiograph ( Fig 3 , C ) shows that all teeth were present.

| Measurement | Pretreatment | Posttreatment | 2 years posttreatment |

|---|---|---|---|

| SNA (°) | 81 | 80 | 80 |

| SNB (°) | 77 | 77 | 77 |

| ANB (°) | 4 | 3 | 3 |

| 1-NA | 7 | 2 | 3 |

| 1:NA | 19 | 19 | 18 |

| 1-NB | 8 | 3 | 3 |

| 1:NB | 33 | 28 | 27 |

| 1:1 | 123 | 129 | 133 |

| Occl:SN (°) | 19 | 17 | 18 |

| GoGn.SN | 37 | 34 | 35 |

| S-LS | 0 | −2 | −2 |

| S-LI | +4 | −1 | −1 |

| Y-axis to FH | 61 | 60 | 60 |

| NPog.FH | 83 | 84 | 84 |

| Angle of convexity (°) | 9 | 6 | 6 |

| Wits (mm) | −1 | +1 | +1 |

| FMA (°) | 34 | 29 | 29 |

| FMIA (°) | 49 | 55 | 56 |

| IMPA (°) | 97 | 96 | 95 |

| Nasolabial angle (°) | 113 | 116 | 117 |

| A-NPerp | −3 | −3 | −3 |

| Co-A | 93 | 93 | 92 |

| Co-Gn | 115 | 118 | 120 |

| AIFH (mm) | 70 | 70 | 70 |

| Pog-NPerp | −13 | −11 | −11 |

Treatment alternatives

Extraction of 4 first premolars was considered to eliminate the crowding, protrusion of the lower lip, and midline deviation. Both conventional (including cervical headgear for maximum anchorage) and rapid canine distraction procedures were explained to the patient and his parents. The skeletal cephalometric measurements were within the normal ranges, so orthognathic surgery was not indicated, and the patient did not want a surgical procedure. He preferred the rapid orthodontic treatment.

Treatment progress

A custom-made intraoral distraction device was fabricated from a hyrax expander (reference 65.05.013; Morelli, Sorocaba, São Paulo, Brazil), which was trimmed, ground, and polished ( Fig 4 ). After construction of the distractor screw, it was soldered to the bands of the first molars and the canines that had been previously transferred to a dental cast. Before soldering to the bands, the distractor screw was opened an amount equal to the mesiodistal width of the premolar to be extracted.

The distractor was cemented, and the premolar was extracted under local anesthesia on the next day ( Fig 5 , A – C ). The surgical procedure was previously described by Liou and Huang. After the premolar extraction, the bone in the premolar socket was grooved vertically with 45° bur cuts along the buccal and lingual aspects, extending obliquely toward the base of the interseptal bone to weaken the resistance. The distractor was activated 0.75 mm per day right after the extraction until the canine was distracted into the desired position.

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses