Dental implants are an indispensible tool for the restoration of missing teeth. Their use has elevated the practice of dentistry by improving both our technical ability to rehabilitate patients and general quality of life. To routinely achieve the associated high expectations, diligent attention to details must be observed and addressed from the outset. Of central concern is the attainment of osseointegration and the location of implants to ideally support the intended restoration. The pivotal point in treatment planning for dental implants occurs when the location of bone is viewed radiographically in the context of the planned prosthesis. This most often requires diagnostic waxing or tooth arrangement using mounted diagnostic casts.

Key points

- •

The development of a complete systemic health evaluation with particular emphasis on factors influencing osseointegration is a first step in the evaluation of implant patients.

- •

An assessment of the overall oral health and ability of patients to maintain ideal oral health is a key step in characterizing potential dental implant patients.

- •

Without mounted diagnostic casts and simple intraoral and perioral photographs, it is nearly impossible to make the proper assessment of local conditions that impact the delivery of successful dental implant prostheses.

- •

An important step in the evaluation of implant patients is the radiographic assessment of osseous architecture and quality in relationship to the contours of the planned dental prosthesis.

- •

Sufficient information to safely and effectively place a dental implant includes the spectrum of diagnostic data that includes the representation of the osseous condition of the intended implant site.

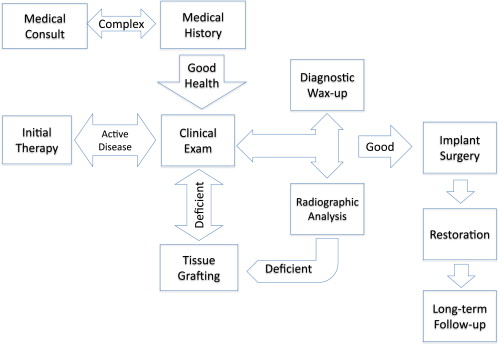

Dental implants have become an indispensible tool for the restoration of missing teeth. Their use has elevated the practice of dentistry by improving both our technical ability to rehabilitate patients and improving general quality of life. To achieve the associated high expectations on a routine basis, diligent attention to details must be observed and addressed from the outset. Of central concern is the attainment of osseointegration and the location of implants to ideally support the intended restoration. The pivotal point in treatment planning for dental implants occurs when the location of bone is viewed radiographically in the context of the planned prosthesis. This diagnostic and planning procedure can only be achieved with the use of a well-designed and constructed radiographic guide (covered in the article by De Kok and colleagues elsewhere in this issue). Notably, the American Dental Association’s recommended guidelines for cone beam computed tomography (CBCT) imaging include its use only after a complete clinical evaluation. It is the intent of this report to review the clinical factors that should be considered in the evaluation of dental implant patients.

Patient selection

Successful patient selection depends on several key factors concerning the patients’ systemic health, the condition of the jaws, and local factors around the proposed implant site. There are few absolute contraindications to implant placement. However, each individual patient presents unique features, and the clinical and radiographic evaluation of individuals accumulates a personal set of risk factors affecting implant outcomes. When selecting patients for implant therapy, it is crucial to obtain a thorough health history to identify conditions that may affect suitability for surgery as well as implant survival ( Box 1 ).

-

Absolute contraindications

-

Osteopathies and disorders of bone metabolism

-

Renal insufficiency and uremia

-

Liver disease

-

Hyperthyroidism

-

Hypopituitarism

-

Connective tissue diseases and specific autoimmune diseases (lupus)

-

Leukopoietic and erythropoietic disease (eg, coagulopathies, plasmacytoma)

-

High-dosage radiotherapy

-

-

Relative somatic conditions

-

Osteoporosis

-

Aggressive rheumatoid arthritis

-

Treated endocrine disorders

-

Anticoagulant treatment

-

Drug and alcohol abuse

-

Low-dosage radiotherapy

-

-

Temporary contraindications

-

Transient infections

-

Systematic therapies affecting wound healing

-

Anticoagulant

-

Immunosuppressive therapy

-

Corticosteroids

-

Chemotherapy

-

-

One of the most important effectors of implant placement and success is the use of alcohol and tobacco products. Several studies have demonstrated that regular alcohol consumption can cause changes in alveolar bone healing, affecting osseointegration and resulting in greater implant failure. The use of tobacco products has been shown to be an even greater detriment not just to the initial placement of implants but to the long-term health and stability. Tobacco use has been shown to increase the chances of initial implant failure by more than 2 times compared with those who do not use tobacco. Smoking negatively impacts healing and damages the delicate tissues around dental implants and has been demonstrated to have a negative effect on several types of bone grafting, limiting the acceptability of potential implant sites. Lastly, the use of tobacco products has been shown to cause complications in fully osseointegrated implants leading to greater chances of long-term implant failure.

In addition to the social habits affecting implant placement, several systemic conditions have been shown to have a negative effect on implant healing and long-term success. The most well-documented condition for affecting implant success is diabetes. Diabetes has been shown to have a wide effect on healing by affecting microvascular health and regeneration as well as cellular responses to trauma. Several studies have demonstrated that this loss of healing potential affects both bone grafting success and implant osseointegration potential, with early failures occurring more frequently compared with nondiabetic patients. It should be noted though that although diabetes should be considered a confounding factor, patients with well-controlled diabetes have been shown to have only slightly worse success rates compared with nondiabetic patients.

Another factor to consider is the presence of osteoporosis. Although it is reasonable to consider that a disease leading to the decalcification of the bones would have an effect on osseointegration, it should not be considered a definitive contraindication because studies have shown that the jaw calcification is only moderately dependent on calcification of the long bones of the body. What is of greater concern for the dentist is the pharmacologic agents used to treat osteoporosis, namely, bisphosphonate drugs. Although the risk of bisphosphonate-induced osteonecrosis is a greater risk for those patients receiving intravenous drug therapy, there have been reports of patients developing osteonecrosis while on oral bisphosphonates. Although some estimates place the risk of osteonecrosis at 7.8%, with literature reports ranging from 2.5% to 27.3% for oral bisphosphonates, it is important to advise patients of the potential complications and place implants only after a careful risk-benefit analysis.

It is also essential to consider patients with various vascular and heart conditions. Several of our elderly patients can be on various heart medications either for hypertension or anticoagulation therapy. Although neither of these classes of drugs should be used as a contraindication, it is important to note that they can pose complications for the initial implant surgery. Those patients on anticoagulant therapy should be evaluated for their PTT and PT/INR, and drug holidays should be considered only after consultation with their primary care physician and/or cardiologist. With regard to hypertensive patients, careful monitoring of blood pressure should be performed to ensure suitability for dental surgery and to limit the risk of a cardiac incident. The development of a complete systemic health evaluation with particular emphasis on factors influencing osseointegration is a first step in the evaluation of implant patients .

Local Factors

When considering the placement of oral implants, it is important to consider the entire oral health of patients. Although it may seem practical to follow a tactical approach of replacing teeth with implants as needed, a more thoughtful strategic approach considered after careful evaluation of the mouth may provide greater restorative options and allow for greater resource management. While implants are not susceptible to oral caries, it is an overall indicator of the patients’ oral hygiene and awareness and serves as one indicator of patients’ future ability to maintain implant hygiene. In addition, removal of active caries allows for the better planning of dental implants by understanding the restorative viability of the teeth. Failure to do so can result in additional surgery or delayed restorative delivery as other dental matters are addressed.

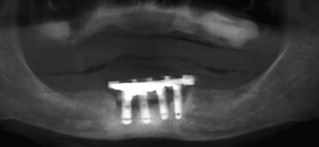

Also of great concern is periodontitis. Periodontal disease is one of the chief causes of tooth loss. There have been several studies that have demonstrated that periodontal disease increases the likelihood of periimplantitis. Periimplantitis is a serious complication for dental implants that can result in implant failure caused by the loss of bony support around the implant ( Fig. 1 ). Although several factors are required to develop periimplantitis, the presence of periodontal oral bacteria can increase the likelihood of its development. In fact, Mombelli and Lang demonstrated a mechanism whereby anaerobic bacterial plaque formations on the implant abutment surface have a negative effect on peri-implant tissues. Most treatments for periimplantitis are palliative in nature and usually only function to arrest the process rather than cure it. Grafting around dental implants to replace the missing bone has been shown to have only limited effectiveness. An assessment of the overall oral health and ability of patients to maintain ideal oral health is the next step in characterizing potential dental implant patients .

The local conditions at the intended site of implant placement merit attention only following the general systemic and oral evaluations. Before any radiographic assessment of the intended implant site is performed, important assessments of local conditions should be considered ( Box 2 ). More succinctly, the architecture of the implant site, the soft tissue anatomy and health of the local site, and the relative aesthetic impact of the intended site must be fully assessed. Both study casts and intraoral photographs are necessary tools in completing these assessments in an efficient manner that allows rapid clinical data collection and subsequent thoughtful evaluation ( Fig. 2 ).

-

Unresolved bone loss attributed to the following:

-

Osteomyelitis, osteoradionecrosis, fibrous bone dysplasias

-

Apical periodontitis

-

Existing residual roots

-

-

Unresolvable bone deficiencies

-

Vertical bone volume of posterior maxilla or mandible

-

Horizontal deficiencies without resolution

-

-

Adjacent tooth limitations

-

Root proximity

-

Aesthetic limitations

-

-

Soft tissue and mucosa

-

Pathologic conditions

-

Deficient attached gingival at proposed implant site

-

-

Oral hygiene

-

Evidence of unwillingness to perform hygiene

-

Local factors that preclude performance of oral hygiene

-

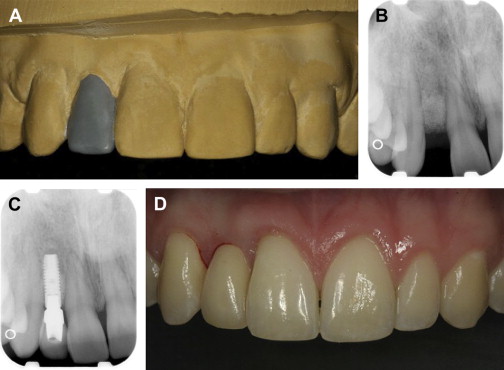

The architecture of the implant site refers to the actual shape and dimension of the intended implant site and the conditions of the teeth, which often frame the site. Although the exact bone volume required to house an implant is not well defined, at least 1 mm of circumferential bone with 1.5 mm of bone between an implant and the adjacent tooth provides sufficient volume to stabilize the implant. Given that many narrow-diameter implants are approximately 3 mm in diameter, the smallest edentulous space that can be predictably restored is 6 mm by 6 mm ( Fig. 3 ). The evaluation of a planned implant site cannot be a simple matter of space measurements because successful planning requires the analysis of soft and hard tissue anatomy, adjacent tooth condition, interdental spatial relationship, and the desired aesthetic outcome.

The soft tissue anatomy of the intended implant site must be well defined. The abundance or lack of keratinized mucosa, the biotype (thickness of the mucosa), and the location of adjacent tooth connective tissue attachments and gingival margins must be defined. This information can be readily assessed in anesthetized patients by bone sounding and periodontal probing ( Fig. 4 ). The lack of keratinized mucosa, a thin biotype, and the loss of connective tissue attachment are known risk factors affecting the aesthetic success of dental implants.

The relative aesthetic impact of the intended implant site must be acknowledged. Anterior sites including the first premolar sites may present sufficient osseous dimension for successful implant placement but may, at the same time, be deficient and result in marked aesthetic deficits ( Fig. 5 ). When larger prostheses are involved, any local architectural change of the alveolus that leads to marked asymmetry of gingival display or leads to the presentation of large gingival embrasures should be identified. Regarding the maxillary or mandibular fixed prostheses, the location of the prostheses/alveolus finish line must be considered. The potential display of this finish line must be aesthetically managed through treatment planning.

Without mounted diagnostic casts and simple intraoral and perioral photographs, it is nearly impossible to make the proper assessment of local conditions that impact the delivery of successful dental implant prostheses.

Adjacent tooth conditions are also important in the consideration of dental implants. Anterior tooth loss is often attributed to recent or past trauma. The condition of the adjacent teeth must be fully defined. Visual inspection, periodontal probing, and vitality testing should be performed. The near zone connective tissue attachment levels should be measured and defined. The radiographic assessment is discussed later. The color of adjacent teeth and the condition of possible existing restorations should be considered for potential repair or replacement; here, the added value of photography is underscored. The management of the vitality and the appearance of adjacent teeth represent an important part of site development for dental implant therapy.

Another key but often overlooked is that of interdental relationships. It is important to address the dimensions of bound and unbound edentulous spaces both regarding adjacent teeth and between antagonistic teeth. Changes encountered lead to both increased and reduced dimensions. Alveolar ridge resorption following tooth loss is now well characterized. The alveolar process begins to collapse, resulting in less bone both in a vertical occlusal-apical direction and in the horizontal buccolingual direction. Although socket preservation surgery has been proposed as a means to preserve bone height and width, resorption will continue to occur. In posterior regions, this resorption can result in limited available bone before reaching critical structures, such as the maxillary sinus or the inferior alveolar nerve in the mandible. The third step, the evaluation of local conditions affecting dental implant therapy, is only fully achieved using mounted diagnostic study casts .

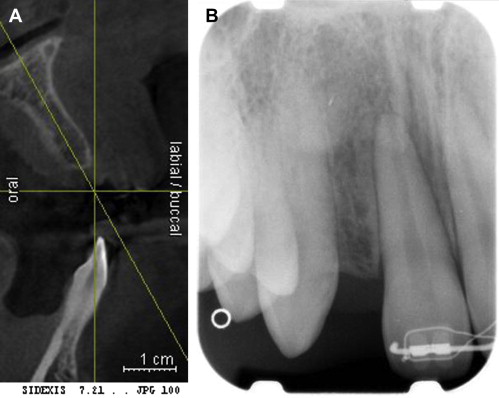

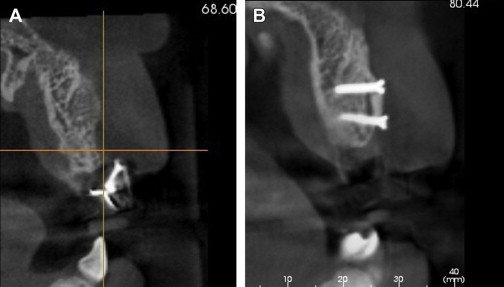

At this point in the evaluation of dental implant patients, the role of radiology has yet to be introduced. There are 2 main reasons for this relegated role for radiographs. First, in practical terms, many of the systemic and aesthetic risks affecting implant therapy cannot be readily modified (eg, diabetes or loss of attachment at adjacent teeth), and it is important to define what cannot be modified first. Bone volume, particularly horizontal bone dimension, can be enhanced by a wide number of clinical procedures that are highly successful ( Fig. 6 ). Although bone volume is critical for implant placement, the initial available volume does not eliminate the possibility of eventual implant placement. Second, radiation safety requires that patient exposure be limited according to the principle of being as low as reasonably achievable; this implies that planning radiographs for dental implants be exposed only after the diagnostic waxing of the planned prosthesis and development of an illustrative radiographic stent. Based on this logic, the diagnostic process for dental implant therapy is fully revealed. After the stepwise consideration of systemic health, followed by oral health, and the clinical assessment of the intended implant site using mounted diagnostic casts, a proposed restoration is modeled using wax (or digital techniques). The location of the proposed restoration must now be revealed in the exposed radiographic assessment of the intended implant site. That location can be revealed using several radiopaque materials that define the full contour of the restoration. In this way, it is now possible to solve the geometric puzzle of reconciling the position of the restoration with the possible implant position ( Fig. 7 ). The fourth step in the evaluation of implant patients is the radiographic assessment of osseous architecture and quality in relationship to the contours of the planned dental prosthesis.

What is the appropriate radiographic imaging technique for dental implants? Although debated, there are guidelines that indicate the volumetric assessment of implant patients using CBCT imaging is of growing importance. Regarding the anterior maxillary aesthetic zone, periapical radiographs remain important because they assist in evaluation of adjacent tooth connective tissue attachment and bone levels that aid in control of aesthetics. Panoramic radiographs may be sufficient for mandibular overdenture therapy involving 1 or 2 implants in the parasymphyseal mandible when the intended implant location is 5 to 10 mm medial to the inferior alveolar nerve bilaterally. Other implant therapies begin to involve considerations whereby the value of CBCT imaging is easily recognized. Sufficient information to safely and effectively place a dental implant includes the entire spectrum of diagnostic data that includes the representation of the osseous condition of the intended implant site .

Implant components, being of fixed and limited vertical dimensions require a defined restorative space represented by the space existing between antagonistic teeth or the tooth and the opposing edentulous ridge. Although initial residual bone measurements can be made from a panoramic radiologic examination, 3-dimensional computed tomography imaging should be considered to ensure that there is adequate space for the implant. In anterior regions, the loss of vertical bone height can result in implants placed lower than the cementoenamel junctions of neighboring teeth, resulting in gingival margin discrepancy ( Fig. 8 ). Although a low smile line can sometimes mask this discrepancy, this can be an aesthetic challenge for patients with the proverbial gummy smiles.

In a similar fashion, tooth loss can result in a loss of bone width. The loss of the root causes the collapse of the buccal plate toward the lingual. In the posterior, this may not be a large concern; but in the anterior in particular, this can cause major aesthetic and functional challenges. For maxillary cuspids, this loss of buccal bone results in obliteration of the canine eminence resulting in teeth that either have higher-than-expected gingival margins or teeth placed more palatally than preferred for the arch form ( Fig. 9 ). The situation is equally dire for lateral incisors whereby the horizontal bone loss could compromise a site to the point that an implant is not an aesthetically viable option. Complicating the matter is any adjacent teeth that may be present. On the loss of a tooth, natural tooth crowding may result in further constriction of the proposed implant site. In addition, proximal root convergence particularly in the anterior regions can result in potential sites too limited for conventional implant therapy.