Treatment of complex pan-facial fractures can present unique challenges. Pan-facial trauma results in severe injury to the hard and soft tissues of the face and associated structures. These fractures are often comminuted and treatment must be individualized for each patient. These injuries are frequently complicated by concomitant injuries that can delay early repair. Inadequate early treatment often leads to secondary deformities that are difficult to treat. With the availability of detailed imaging, rigid fixation, primary bone grafting, proper sequencing, and soft tissue resuspension, outcomes can be optimized.

Etiopathogenesis/Causative Factors

Patients with pan-facial fractures represent a small proportion of the overall patient population with facial fractures. Because of the force necessary to cause pan-facial injury, these patients often have other concomitant injuries. Late complications can also occur with these fracture patterns. Follmar and colleagues found that 53% of their patients had concomitant injuries, with intracranial injury or hemorrhage being the most common. Mithani and co-authors reviewed 4786 patients treated for facial fractures and found that among all those with facial fractures, 461 (9.6%) also had cervical spine injuries and 2175 (45.4%) had associated head injuries. Fractures of the upper part of the face were associated with an increased likelihood for mid to lower cervical spine injuries, severe intracranial injuries, and increased mortality rates. Bilateral mid-face injuries were associated with basilar skull fracture and death. Cranio-maxillofacial fractures are commonly associated with head and cervical spine injuries that involve predictable patterns of dispersion of force from the maxillofacial skeleton and transmission to the cranial vault and cervical spine. Concomitant injuries should be investigated closely with distinct types of facial fractures.

Pathologic Anatomy

The anatomic patterns of fractures provide a useful framework for classifying these injuries. By categorizing the fracture patterns and highlighting the variables that may affect fracture management, surgeons can expand interpretation of the fracture pattern into a clinically useful diagnosis that affects fracture management. Markowitz and associates described a useful classification system for naso-orbito-ethmoid (NOE) fractures based on the central bone fragment that provides attachment to the medial canthal tendon.

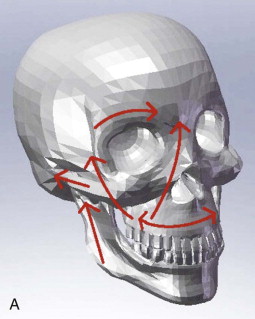

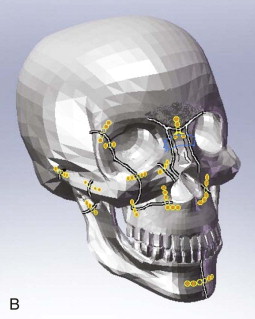

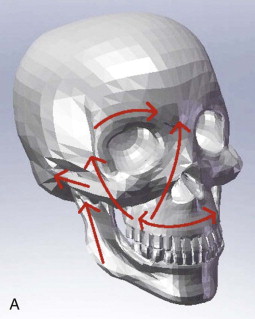

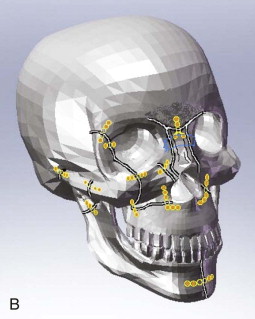

The buttress system of the face absorbs and transmits forces and includes horizontal and vertical buttresses ( Fig. 44-1 ). The vertical buttresses include the nasomaxillary (including the maxillary process of the frontal bone), zygomaticomaxillary, and pterygomaxillary buttresses and the posterior mandible (including the condyle and posterior mandibular ramus). In reconstructing pan-facial fractures, particular attention should be directed to restoring these buttresses to provide the most stable result. The pterygomaxillary buttress is not typically reconstructed because of difficulty accessing it.

Pathologic Anatomy

The anatomic patterns of fractures provide a useful framework for classifying these injuries. By categorizing the fracture patterns and highlighting the variables that may affect fracture management, surgeons can expand interpretation of the fracture pattern into a clinically useful diagnosis that affects fracture management. Markowitz and associates described a useful classification system for naso-orbito-ethmoid (NOE) fractures based on the central bone fragment that provides attachment to the medial canthal tendon.

The buttress system of the face absorbs and transmits forces and includes horizontal and vertical buttresses ( Fig. 44-1 ). The vertical buttresses include the nasomaxillary (including the maxillary process of the frontal bone), zygomaticomaxillary, and pterygomaxillary buttresses and the posterior mandible (including the condyle and posterior mandibular ramus). In reconstructing pan-facial fractures, particular attention should be directed to restoring these buttresses to provide the most stable result. The pterygomaxillary buttress is not typically reconstructed because of difficulty accessing it.

Diagnostic Studies

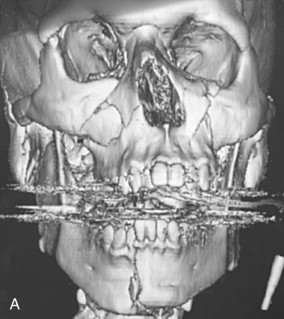

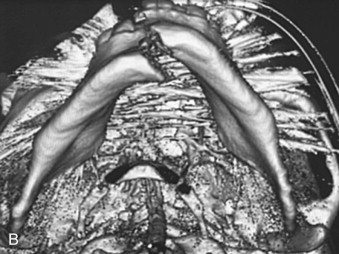

Computed tomography (CT) has greatly added to the preoperative appreciation of the extent of fractures. It allows one to formulate a treatment plan, including surgical approaches and the sequencing of fracture repair. Axial, coronal, and sagittal views are helpful, as well as three-dimensional views, especially in patients with severely comminuted fractures ( Fig. 44-2 ). Three-dimensional CT has not been shown to have increased accuracy for identifying mandibular fractures and is associated with decreased visualization of the soft tissues and deep internal architecture of the orbits. Two-dimensional CT more accurately displays injuries involving the paranasal sinuses, orbital walls, and soft tissues. CT combined with navigation also provides the clinician with a technique that can optimize treatment. Intraoperative CT allows more precise reduction of fractures and is especially useful for severe pan-facial fractures, as well as large orbital fractures.

Treatment/Reconstructive Goals

The goals of treatment are to restore the face to as close to the pre-injury state as possible. This is accomplished by accurate reduction and fixation of the various fractures with special attention directed at restoring facial height, width, and projection. Treatment should focus on restoring both form and function while minimizing the need for secondary surgery.

Sequence of Reduction

Treatment of pan-facial fractures has changed significantly with the advent of rigid fixation, which allows more flexibility in the sequence of repair. The basic key to reconstruction is restoration of facial width, projection, and height. Much has been written about the sequencing of treatment of pan-facial fractures. There are two commonly advocated approaches, with variations, to sequencing of the treatment of pan-facial fractures, including sequences such as “top to bottom and outside-in” or “bottom to top to middle.” Gruss and co-workers applied plate and screw fixation to pan-facial fractures in a “top-to-bottom” approach. They advocate reconstruction of the outer facial frame beginning with the zygomatic arch, zygoma, and frontal bar. The inner facial frame (NOE complex) is reduced and stabilized, followed by the internal orbit. The maxilla (Le Fort I level) is then repositioned by aligning it with the now stabilized mid-facial buttresses. Maxillomandibular fixation (MMF) is then used to restore the position of the mandible, which is fixated last. This approach does not require reduction and fixation of fractures involving the condylar region.

Others, such as Kelly and colleagues, advocate a “bottom-to-top-to-middle” approach. This approach begins with reconstruction of the mandible, including subcondylar fractures, and placement of MMF. Once the maxillomandibular complex is reconstructed, the frontal and temporal regions are addressed. Naso-orbital fractures are reduced and stabilized. The outer facial frame is reconstructed beginning at the arch to restore facial projection. The internal orbit is reconstructed after the entire upper part of the face and the upper mid-face are repaired. Finally, reduction and fixation across the Le Fort I level are accomplished, with placement of bone grafts as necessary.

The exact sequence of exposure should be organized according to the clinical findings and fracture patterns of each individual patient. Principles to follow include exposure of multiple fractures before fixation, fixation of fractures that are most stable and able to be anatomically reduced most precisely, and utilization of the occlusion to link the mandible to the lower mid-face. This author most commonly uses a bottom-up and outside-in approach based on these principles ( Figs. 44-3 and 44-4 ). This is predicated on restoring the major vertical buttress in the lower part of the face by opening and fixating fractures involving the subcondylar region. However, if a condylar fracture is extremely comminuted or not conducive to open treatment, it will be necessary to rely on other areas for restoration of posterior facial height ( Fig. 44-5

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses