This overview covers diagnosis and management of the most common dental injuries in children and identifies those children at greatest risk. Crown fractures and luxation injuries in both the primary and permanent dentition are discussed and treatment options based on current international guidelines are detailed.

Key Points

- •

Falls are the most frequent cause of dental trauma among preschool and school-age children. Sports-related injuries and altercations are more common in adolescents. Dental trauma may be an indication of child abuse.

- •

Dental injuries are a subset of head trauma. The history in children with dental trauma should include the time, place, and mechanism of the injury and a thorough neurologic history.

- •

Avulsed primary teeth should not be reimplanted.

- •

Avulsed permanent teeth should be reimplanted immediately by the first capable person (eg, the injured child, a parent, teacher, coach, neighbor.) If immediate replantation is not possible the tooth should be stored in cold milk or in a cup with the child’s saliva. It should not be stored in water.

Managing injuries to children’s teeth in the primary and early mixed dentitions can be challenging. Injured children and their parents are often anxious and this can complicate the provision of prompt, appropriate care. The clinician must be able to assess the injury, prioritize treating those problems that require immediate attention, and minimize the child’s fear and anxiety.

An excellent online resource for current treatment guidelines is The Dental Trauma Guide ( http://www.dentaltraumaguide.org ). This guide, developed by Dr Jens O. Andreasen and sponsored in part by the University Hospital, Copenhagen and the International Association for Dental Traumatology (IADT), contains updated guidelines on a broad array of dental injuries and is easy to use.

Epidemiology and cause

Differences in study design and sampling criteria make precise estimates of the incidence and prevalence of dental injuries difficult to determine. Up to 40% of preschool children suffer injuries to their primary teeth, with the peak incidence occurring in the toddler stages (2 to 3 years), when young children are developing their mobility skills. Falls during play account for most injuries to young permanent teeth. Children who participate in contact sports are at greater risk for dental trauma, although the use of mouth guards reduces their frequency. Automobile accidents cause many dental injuries in the teenage years, particularly when occupants not wearing seatbelts hit the steering wheel or dashboard. Many apparently minor dental injuries go unreported, so it is safe to assume that up to half of all children suffer some dental trauma.

Maxillary central incisors are the most commonly injured teeth, followed by the maxillary lateral incisors and the mandibular incisors. The ability of the upper lip to protect the maxillary teeth is affected by the degree of prominence of the anterior teeth ( Fig. 1 ). The normal horizontal distance between the maxillary and mandibular incisors (overjet) is between 1 and 3 mm. Overjets greater than 4 mm increase the likelihood of dental trauma by 2 to 3 times.

Dental trauma may be an important clinical marker for child abuse, because up to 50% to 75% of all cases involve some form of orofacial injury.

Potential signs of child abuse include:

- •

Bruises in various stages of healing indicating multiple traumatic incidents

- •

Torn upper labial frena

- •

Bruising of the labial sulcus in young, preambulatory patients

- •

Bruising on the soft tissues of the cheek.

Epidemiology and cause

Differences in study design and sampling criteria make precise estimates of the incidence and prevalence of dental injuries difficult to determine. Up to 40% of preschool children suffer injuries to their primary teeth, with the peak incidence occurring in the toddler stages (2 to 3 years), when young children are developing their mobility skills. Falls during play account for most injuries to young permanent teeth. Children who participate in contact sports are at greater risk for dental trauma, although the use of mouth guards reduces their frequency. Automobile accidents cause many dental injuries in the teenage years, particularly when occupants not wearing seatbelts hit the steering wheel or dashboard. Many apparently minor dental injuries go unreported, so it is safe to assume that up to half of all children suffer some dental trauma.

Maxillary central incisors are the most commonly injured teeth, followed by the maxillary lateral incisors and the mandibular incisors. The ability of the upper lip to protect the maxillary teeth is affected by the degree of prominence of the anterior teeth ( Fig. 1 ). The normal horizontal distance between the maxillary and mandibular incisors (overjet) is between 1 and 3 mm. Overjets greater than 4 mm increase the likelihood of dental trauma by 2 to 3 times.

Dental trauma may be an important clinical marker for child abuse, because up to 50% to 75% of all cases involve some form of orofacial injury.

Potential signs of child abuse include:

- •

Bruises in various stages of healing indicating multiple traumatic incidents

- •

Torn upper labial frena

- •

Bruising of the labial sulcus in young, preambulatory patients

- •

Bruising on the soft tissues of the cheek.

Evaluation

History

Knowing when, where, and how the injury occurred assists the clinician in determining the severity of the injury. The time that has elapsed since the injury took place affects the treatment and, in most cases, the prognosis. Knowledge regarding the mechanism of injury helps to determine the severity of the injury and the risk of associated injuries. A thorough neurologic history should be obtained, because dental injuries are a subset of head trauma. The patient should be promptly referred for medical evaluation of a potential closed head injury if any of the following signs are present:

- •

Dizziness

- •

Headache

- •

Nausea/vomiting

- •

Loss of memory

- •

Loss of consciousness

- •

Lethargy or irritability

As noted earlier, the possibility of child abuse also must be considered. The child’s medical history should be obtained, with particular attention given to medications, drug allergies, and status of tetanus immunization.

Clinical Examination

A thorough clinical examination should include an assessment of:

- •

The facial skeleton to determine discontinuities of facial bones. Extraoral wounds and bruises should be recorded. The temporomandibular joints should be palpated, and any swelling, clicking, or crepitus should be noted. Mandibular function in all excursive movements should be checked. Any stiffness or pain in the child’s neck necessitates immediate referral to a physician to rule out cervical spine injury.

- •

Intraoral and extraoral soft tissues, including the lips, frena, tongue, gingivae, oral mucosa, and palate.

- •

All teeth (anterior and posterior), to rule out fractures, discoloration, displacements, pulp exposures, and increased mobility. Fractures of the posterior teeth may occur after trauma to the chin and are associated with fractures of the mandibular condyles and cervical spine.

- •

Does the child have spontaneous pain in any teeth as a result of the injury? This pain may indicate pulpal exposure or inflammation.

- •

Are any of the teeth tender to touch or the pressure of eating? This symptom indicates periodontal ligament (PDL) damage or displacement.

- •

Are any of the teeth sensitive to hot or cold? This symptom may indicate pulp exposure or inflammation.

- •

Is there a change in the child’s bite or occlusion? This change indicates displaced teeth or possibly a facial fracture.

Radiographic Examination

Radiographs enable the clinician to gather information needed for an accurate diagnosis and plan of treatment. They are useful to determine the

- •

Extent of root development

- •

Position of unerupted teeth

- •

Size of pulp chambers

- •

Relationship between the injured primary teeth and their permanent successors

- •

Periapical radiolucencies

- •

Root fractures

- •

Extent and type of root resorption

- •

Degree of tooth displacement

- •

Jaw fractures

- •

Presence of tooth fragments and other foreign bodies in soft tissues.

Baseline radiographs at the initial appointment are important even if they seem to show negative findings, because they can be compared with subsequent radiographic evidence at follow-up appointments.

Radiographic techniques

All images should clearly show the apical areas of traumatized teeth. The guidelines of the IADT call for multiple images taken from slightly different angles both vertically and horizontally to verify the location and extent of a pathologic condition. Standard anterior occlusal views are appropriate to detect injuries to primary incisors. A lateral anterior view can also be helpful to determine the relationship between an intruded primary tooth and its developing permanent successor ( Fig. 2 ). Exposure times vary depending on the equipment used, but doubling the exposure time is usually sufficient for this view. Film/sensor holding devices should be used to expose periapical images of injured permanent teeth to enable duplication of the same views at subsequent visits. The presence of foreign bodies such as tooth fragments in the lips or tongue can be detected by reducing the normal exposure time. The film or sensor is placed beneath the tissue to be examined, and the radiograph is exposed.

Timing of follow-up radiographs

Many pathologic changes are not immediately apparent in radiographs. It takes approximately 3 weeks to detect periapical radiolucencies that are caused by pulpal necrosis, and inflammatory root resorption may also be evident at this time. After approximately 6 to 7 weeks, replacement resorption, or ankylosis, can be seen. Thus, there is adequate rationale to obtain postoperative radiographs at 1 month after the injury. In the absence of any clinical signs or symptoms, such as development of swelling, fistula, mobility, tooth discoloration, or pain, additional films are not indicated until 6 months after the injury. If changes are to appear radiographically, they usually do so by this time.

Classification of dentoalveolar injuries

Fractures

Trauma to the mouth may cause fractures of the teeth or damage to the supporting alveolar bone and periodontium. Fractures of the crown are classified as complicated (involving the neurovascular pulp) or uncomplicated (involving only the enamel or the enamel and dentin). Horizontal, vertical, and oblique fractures of the root also occur.

Luxation Injuries

Luxation injuries involve the supporting structures of the teeth, including the PDL and alveolar bone. The primary goal in the treatment of luxation injuries is to maintain the vitality of the PDL, which supports the tooth in its socket. Luxation injuries are classified as follows:

- •

Concussion: the tooth is neither loose nor displaced; it may be tender with the pressure of biting because of inflammation of the PDL.

- •

Subluxation: the tooth is loose but not displaced from its socket. The PDL fibers are damaged and inflamed.

- •

Intrusion: the tooth is driven into the socket, compressing the PDL and fracturing the alveolar socket.

- •

Extrusion: the tooth is centrally dislocated from its socket; the PDL is lacerated and inflamed.

- •

Lateral luxation: the tooth is displaced anteriorly, posteriorly, or laterally; the PDL is lacerated and the supporting bone is fractured.

- •

Avulsion: the tooth is completely displaced from the alveolar ridge; the PDL is severed and fracture of the alveolus may occur.

Pathologic sequelae of trauma to teeth

Complications after traumatic injuries to teeth may appear shortly after the injury (eg, infection of the PDL or dark discoloration of the crown) or after several months (eg, yellow discoloration of the crown and external root resorption). It is not possible to accurately identify the histopathologic condition of a dental pulp based on clinical symptoms. The following terms describe a spectrum of clinical signs and symptoms that accompany inflammation and degeneration of the pulp or PDL.

Pulpitis

Pulpitis is the initial response of the tooth to trauma and it accompanies almost every injury. Signs include sensitivity to percussion and capillary congestion, which may be clinically apparent from the lingual surface of the tooth using transillumination. Pulpitis may be reversible in minor injuries or may progress to irreversible pulpitis and pulp necrosis.

Pulp Necrosis

Injured pulps may lose their vitality either because of damage to the vascular tissue at the apex and the resulting ischemia or because of necrosis of exposed coronal pulp tissue. If the necrotic pulp becomes infected with oral microorganisms either because of luxation of the root and ingress through the lacerated PDL or via an exposed pulp, pain and root resorption can occur. In the primary dentition, extraction is indicated to prevent damage to the permanent successor. A pulpectomy is indicated in the permanent dentition. When the necrotic pulp is not infected, it may remain asymptomatic, both clinically and radiographically.

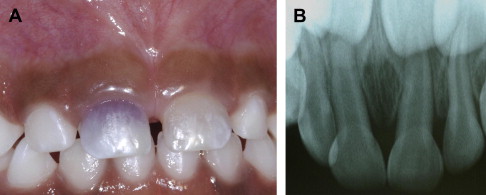

Tooth Discoloration

Injuries to the primary incisors frequently cause tooth discoloration ( Fig. 3 ). Blood vessels within the pulp chamber can rupture, depositing blood pigment in the dentinal tubules. This blood may resorb completely or can persist to some degree throughout the life of the tooth. Teeth that discolor are not necessarily necrotic, particularly when the color change occurs within a few days of the injury. However, primary teeth with dark discoloration that persists for months after the injury are likely to be necrotic, but may remain asymptomatic. So, in healthy children, tooth color alone does not dictate treatment of primary incisors. Other signs or symptoms of infection, like periapical radiolucency, pain, swelling, parulis, or increased mobility, should be detected before the tooth is extracted. In the permanent dentition, persistent, dark discoloration indicates that pulp necrosis is likely and a pulpectomy is indicated.

A yellowish discoloration of both primary and permanent teeth may occur if they undergo pulp canal obliteration (PCO).

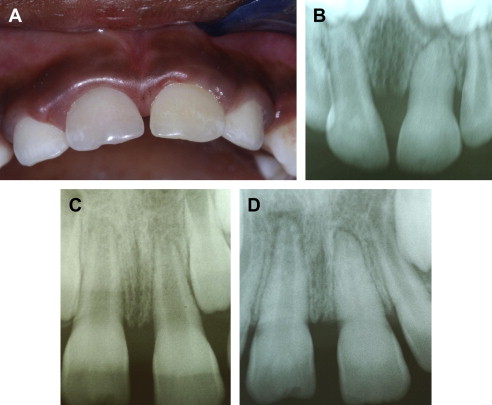

PCO

PCO is a common finding in luxated primary incisors, particularly when the injury occurred before completion of the root development of the tooth. It is also associated with luxation injuries to permanent incisors, and, again, is most common in those with incomplete root development ( Fig. 4 ). The entire pulp chamber and canal appear radiopaque in radiographs and the crown may have a yellowish color. The process of accelerated dentinal apposition in PCO is not well understood, but primary teeth with PCO tend to resorb normally. Pulp necrosis is rare in teeth with PCO and root canal treatment is rarely indicated in either the primary or permanent dentitions.

Inflammatory Resorption

Inflammatory resorption can occur internally or externally. It is related to an infected pulp and an inflamed PDL. It can resorb roots quickly and, in the primary dentition, this inflammatory process can damage developing teeth, so extraction of the offending tooth is indicated. In the permanent dentition, inflammatory resorption can be radiologically evident within several weeks of an injury ( Fig. 5 ). It is treated by removing the pulp and applying calcium hydroxide.