An open-bite malocclusion with a tongue-thrust habit is a challenging type of malocclusion to correct. A 12-year-old girl came for orthodontic treatment with a severe anterior open bite, extruded posterior segments, a tongue-thrust habit, and lip incompetency. Her parents refused surgical treatment, so a nonextraction treatment plan was developed that used palatal temporary skeletal anchorage devices for vertical control and mandibular tongue spurs to reeducate the tongue. Interproximal reduction was also used to address the moderate to severe mandibular crowding. An abnormal Class I occlusion was achieved with proper overbite and overjet, along with a pleasing smile and gingival display.

Highlights

- •

Vertical control was obtained with a transpalatal arch supported by a temporary anchorage device.

- •

The tongue can be reeducated with mandibular spurs.

- •

The open bite was stable after retention.

The etiology of open bites remains controversial and in some cases unanswered. However, there is agreement about the difficulties of treating patients with the dental and skeletal characteristics associated with this vertical discrepancy. Dental open bites are a specific type of malocclusion caused primarily by local or environmental factors. Often local etiology is correlated with habits or trauma. When a skeletal component is present, the etiology menu incorporates heredity and other health-related issues including allergies, hypertrophy of the lymphatic tissues, muscular hypotonicity, syndromes, and neurologic problems as possible contributors to the malocclusion. The literature cites causes and effects of inherited skeletal patterns (eg, vertical maxillary excess) caused by a digit-sucking habit, a tongue-thrust habit, supererupted posterior teeth, and an airway obstruction among the most prevalent causes of an open bite.

Many treatment modalities have been tested, some with varying degrees of success. Often, a treatment option is highly correlated with the severity of the malocclusion. Some less complex open bites may resolve by themselves during the transition from the mixed to the permanent dentition. Others require complex modalities, including extraction of permanent teeth, intrusion of the posterior dentition, extrusion of the anterior dentition, or orthognathic surgery (predominately maxillary impaction).

Most recently, the use of temporary anchorage devices (TADs) has supported treatment options without surgery or extractions. At present, many complex types of malocclusions can be treated orthodontically with TADs. TADs can provide skeletal anchorage to move teeth in all directions, giving clinicians minimally invasive treatment modalities that were not possible previously. They can also aid in the treatment of open bites by providing adequate anchorage for the intrusion of posterior teeth with a transpalatal arch (TPA). The TPA is attached to palatally placed TADs with power chains or closed-coil springs. Intrusion of the posterior maxillary dentition allows autorotation of the mandible and therefore closure of the anterior open bite. Depending on a comprehensive diagnostic protocol including the severity of the malocclusion, this technique allows for a treatment option that eliminates the need for surgical impaction of the maxilla.

Diagnosis and etiology

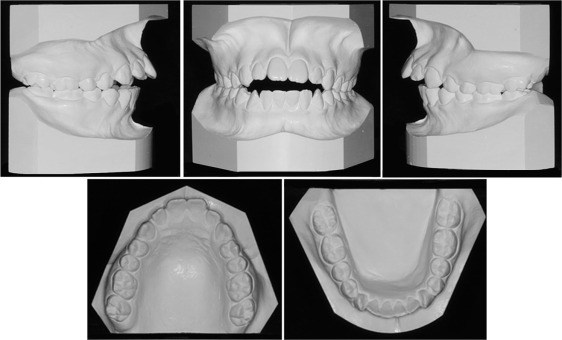

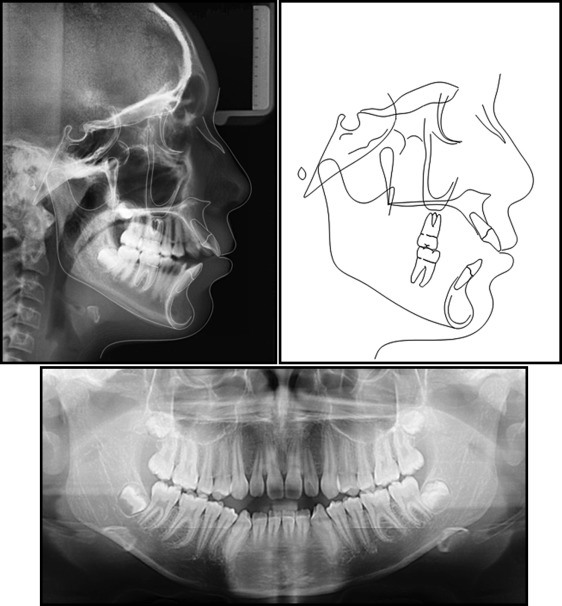

A 12-year-old female came to the orthodontic clinic with chief complaints of a severe open bite and a history of speech problems. She was in myofunctional therapy at that time. The clinical examination showed an infantile swallowing pattern, anterior resting tongue posture, and a history of mouth breathing. The radiographic and clinical examinations of the temporomandibular joint showed no symptoms. She had normal joint function and joint structure ( Figs 1-3 ).

The patient was diagnosed with a Class I skeletal open bite (FMA, 31.5°), excessive lower anterior facial height (ANS-Me, 67.9 mm), and short upper anterior facial height (N-ANS, 46.0 mm). She had bilateral Class I molars, bilateral Class II canines, a 4-mm open bite, 9 mm of overjet, and coincident midlines ( Table ). Her facial features were leptoprosopic: convex profile (NA–A-Po, 2.9°) and incompetent lips at rest with mentalis and lip strain when the lips were together. She also had a discrete posterior gingival display on smiling.

| Norm | Pretreatment | Final | |

|---|---|---|---|

| SNA (°) | 82 | 80.3 | 78.7 |

| SNB (°) | 80.9 | 77.1 | 76.7 |

| ANB (°) | 1.6 | 3.3 | 2.0 |

| SN-GoGn (°) | 32.9 | 31.9 | 31.6 |

| FMA (°) | 24.6 | 30.7 | 29.9 |

| U1-NA (mm) | 4.3 | 10.5 | 6.6 |

| U1-SN (°) | 102.6 | 119.1 | 102.8 |

| L1-NB (mm) | 4.0 | 6.5 | 7.4 |

| L1-GoGn (°) | 93.0 | 105.3 | 105.1 |

| Lower lip to E-plane (mm) | −2.0 | 2.4 | 0.9 |

| Upper lip to E-plane (mm) | −4.5 | −0.1 | −2.0 |

| NA-APo (°) | 0.0 | 2.9 | −0.7 |

| ANS-Me (mm) | 65.0 | 67.9 | 67.9 |

| N-ANS (mm) | 50.0 | 46.0 | 46.6 |

Treatment objectives

The main treatment objectives were to close the anterior open bite without excessive extrusion of the anterior dentition in an attempt to at least maintain the pretreatment gingival display. This could be achieved through intrusion of the posterior maxillary dentition using TADs as skeletal anchorage. Additional treatment goals included leveling and aligning, reducing the dental protrusion, maintaining the Class I molar relationships, achieving a Class I canine relationship as well as ideal overbite and overjet, improving the facial profile, and obtaining natural lip competence without mentalis strain.

Treatment objectives

The main treatment objectives were to close the anterior open bite without excessive extrusion of the anterior dentition in an attempt to at least maintain the pretreatment gingival display. This could be achieved through intrusion of the posterior maxillary dentition using TADs as skeletal anchorage. Additional treatment goals included leveling and aligning, reducing the dental protrusion, maintaining the Class I molar relationships, achieving a Class I canine relationship as well as ideal overbite and overjet, improving the facial profile, and obtaining natural lip competence without mentalis strain.

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses