This clinical report describes the diagnosis and the management of isolated-type recession defects of complex etiology in 2 healthy postorthodontic patients. The lesions were confined to 1 mandibular incisor and were associated with an abnormal buccolingual inclination of the affected tooth despite a lingual retainer made with a round stainless steel twisted wire. After careful questioning, it was determined that the recession defects were indirect effects of habitual onychophagia. The concomitant fingernail-biting habit and the lingual bonded retainer led to the indirect development of bone dehiscence and, consequently, gingival recession.

Gingival recession is an apical shift of the gingival margin with respect to the cementoenamel junction, and bone dehiscence is the essential anatomic prerequisite for its development. The orthodontic movement of teeth beyond the limits of the labial or lingual alveolar plate can lead to dehiscence formation, thus predisposing the patient to recession when there is inadequate plaque control or traumatic mechanical factors. For this reason, clinicians generally correlate gingival recession with inadequate treatment planning or insufficient biomechanical tooth control during the orthodontic therapy.

This clinical report describes the diagnosis and management of isolated-type recession defects in 2 healthy postorthodontic patients. The lesions affected a mandibular incisor and were associated with an abnormal buccolingual inclination of the affected tooth despite a 6-unit lingual retainer bonded from canine to canine. Toothbrushing trauma and inadequate plaque control were excluded as possible developing factors, as well as orthodontic proclination of the mandibular incisors. Only slight mandibular crowding was present at the initial examination, and Class II elastics were not used during the therapy. The evaluation of these aspects and the distinctive site-specificity of the lesion suggested that a mechanical factor had acted on 1 mandibular incisor. After careful and prolonged questioning, it was discovered that both patients had a habit of pressing their fingernails tightly against the biting edge of the affected tooth, thereby exerting continuous pressure on it. They had been doing this unconsciously for a long time with no previously noticeable sequelae. After the lingual retainer was bonded, any lingual crown movement was prevented; thus, the applied force resulted in buccal root displacement.

The aim of this article was to describe the diagnosis and treatment of 2 postorthodontic isolated gingival defects, in which the concomitant presence of onychophagia and a 6-unit lingual bonded retainer led to the indirect development of bone dehiscence and, consequently, gingival recession.

Case report 1

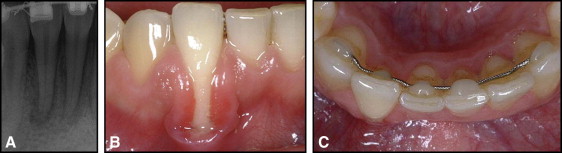

A healthy 22-year-old woman was treated for an Angle Class I occlusion with moderate maxillary and mandibular crowding and anterior deepbite. After 2 years of fixed orthodontic treatment, the appliances were removed, and retention was achieved with a removable Hawley plate in the maxillary arch and a 6-unit lingual retainer, made with a round stainless steel twisted wire bonded from canine to canine, in the mandibular arch. After 5 years of retention, the patient had root prominence and isolated gingival recession at the labial aspect of the mandibular right central incisor ( Fig 1 ). There was also excessive lingual inclination of the root of the mandibular left central incisor ( Fig 2 , A ). The patient had been referred to the orthodontist by her general dentist, who ascribed those anomalous root inclinations to a relapse of the orthodontic treatment. She was greatly concerned that her mandibular incisors might return to their pretreatment positions; in these circumstances, the risk of litigation was high because the orthodontist could not explain the excessive inclination of the affected tooth despite the lingual bonded retainer. A periodontal clinical evaluation confirmed the gingival recession on the labial surface of the buccally dislocated root of the right central incisor, extending 2 mm apically to the cementoenamel junction; the most apical extension of the gingival recession did not extend beyond the mucogingival line ( Fig 2 , A and B ). Facial probing pocket depth did not exceed 1 mm, and 2 mm of keratinized tissue (1 mm of attached gingiva) remained apically to the root exposure. The gingival tissue around the defect appeared healthy with no signs of inflammation, and the exposed root surface was clean with no plaque accumulation or demineralization. Mesial and distal interdental papillae were intact: they filled the embrasure spaces up to the contact points, and there were no pathologic probing pocket depths. The tooth malposition despite the integrity of interdental periodontal support put the gingival defect in the Miller Class III of gingival recession. The soft-tissue margin was coronal to the cementoenamel junction at all other teeth near the tooth with the gingival defect. A 5-mm-high band of buccal keratinized tissue characterized the patient biotype at the adjacent healthy teeth.

A severe nail deformity was detected, a consequence of onychophagia ( Fig 2 , C ).

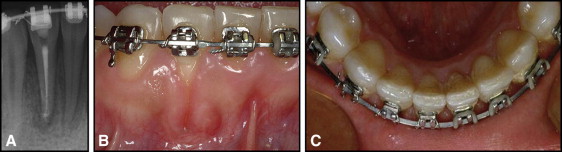

The patient was clearly informed of the need to quit the habit, and she was motivated to resolve the problem. The retainer was removed, and fixed orthodontic treatment was initiated in the mandibular arch, with the goal of repositioning the root of the right central incisor in the alveolar bone by lingual torque movement. The patient was instructed to use a soft toothbrush and a coronally directed roll toothbrushing technique to minimize the brushing trauma to the gingival margin. After 6 months, the correct axial inclination of all mandibular incisors was achieved, the fixed appliances were removed, and a lingual bonded retainer, made of multibraided rectangular stainless steel wire, was placed from canine to canine to ensure optimal control of the tooth positions ( Fig 3 , A and B ).

Complete root coverage was achieved after stopping the habit and completing the orthodontic therapy. The soft-tissue margin was located at the level of the cementoenamel junction, and the facial keratinized tissue was increased (2 mm) with respect to the preorthodontic situation and appeared healthy with no sign of inflammation. Facial probing pocket depth remained shallow (1 mm).

A clinical reevaluation 9 years later showed stability in root coverage, a further increase in the height of facial keratinized tissue (measuring 5 mm), and gingival health around the previously affected tooth and the adjacent teeth ( Fig 3 , C ).

Case report 2

A healthy 18-year-old woman initially had an Angle Class I occlusion with an anterior deepbite and an impacted maxillary right canine. After 18 months of fixed orthodontic treatment, retention was achieved with a removable Hawley plate in the maxillary arch and a 6-unit lingual retainer made with round stainless steel twisted wire, bonded from canine to canine in the mandibular arch.

After 4 years, the patient came with a buccal dislocation of the root and isolated gingival recession at the labial aspect of the mandibular right lateral incisor ( Fig 4 ). Clinical evaluation showed gingival recession extending 3 mm apically to the cementoenamel junction. The most apical extension of the soft-tissue margin did not reach the mucogingival line, and 1 mm of keratinized tissue remained apically to the root exposure. The root malposition despite the integrity of the interdental periodontal support put the gingival defect in the Miller Class III of gingival recession. Facial probing pocket depth was 1 mm, and attached gingiva was absent. Limited areas of “simil-inflammatory tissue” (red, highly vascularized tissue) were present laterally to the root exposure. These areas did not disappear after oral hygiene measures; thus, they were not related to plaque accumulation and did not bleed after superficial probing.

The patient was informed that she would need to quit the nail-biting habit to resolve the problem. The bonded lingual retainer would be removed, and new orthodontic treatment would be needed to reposition the tooth and, it was hoped, treat the gingival defect. Unfortunately, the patient did not accept the treatment plan because she did not want to reapply orthodontic appliances.

One year later, she returned with marked worsening of the isolated gingival recession at the labial aspect of the mandibular right lateral incisor ( Fig 5 ). The clinical evaluation showed root prominence with 7 mm of gingival recession extending beyond the mucogingival line. No keratinized tissue or attached gingiva remained apically to the root exposure. The 8-mm facial probing pocket depth complicated the gingival lesion; thus, facial clinical attachment loss amounted to 15 mm. The depth of the facial clinical attachment loss induced the clinician to test tooth vitality based on the response to electric and cold vitality tests. Both tests were negative, and the periapical radiograph showed an area of translucency around the apex of the tooth, although the interdental bone was intact. The areas of “simil-inflammatory tissue” lateral to the root exposure were expanded and extended along the entire height of the recession defect. These areas showed 3-mm facial-lingual probing pocket depths and still were not related to plaque accumulation and did not bleed after superficial probing.There was bleeding with deep probing of the pockets apical and lateral to the root exposure. Mesial and distal interdental papillae were intact: they filled the embrasure spaces up to the contact points, and no pathologic probing pocket depths were present. The tooth malposition despite the integrity of the interdental periodontal support put the gingival defect in the Miller Class III of gingival recession. The soft-tissue margin was coronal to the cementoenamel juncture at all other teeth near the tooth with the gingival defect. A 4-mm-high band of buccal keratinized tissue characterized the patient biotype at the adjacent healthy teeth.

The patient was greatly concerned about the worsening of the gingival lesion and was therefore willing to undergo orthodontic treatment. The mandibular right lateral incisor was endodontically treated, and the lingual bonded retainer was removed. An oral-hygiene recall visit was scheduled, and gentle subgingival scaling (at the apical and lateral pockets) with an ultrasonic device and polishing of the root exposure were performed. Three weeks later, orthodontic therapy was started. After 6 months of fixed orthodontic treatment, the root of the lateral incisor was replaced in the alveolar bone. The periodontal examination ( Fig 6 ) showed that a 6-mm-high gingival recession extending beyond the mucogingival line still affected the normally positioned lateral incisor. The absence of tooth malposition and the integrity of the interdental periodontal support put the gingival defect, still extending beyond the mucogingival line, in the Miller Class II of gingival recession. No facial keratinized tissue and attached gingiva were present apically to the root exposure, and a 6-mm facial probing pocket depth still complicated the gingival lesion. Facial clinical attachment loss amounted to 12 mm. The width of the root exposure was greatly reduced along the entire height of the root exposure. The areas of “simil-inflammatory tissue” lateral to the root exposure and the facial-lingual probing pocket depths had completely disappeared. The soft-tissue margin at the adjacent teeth was located coronally to the cementoenamel junction, and there was a healthy 4-mm-high band of buccal keratinized tissue mesially and distally to the gingival defect.

A decision to perform root-coverage surgery was made. Various factors influenced the decision not to further postpone the surgery: (1) the difficulty of maintaining good plaque control in the narrow gingival defect, (2) the deep facial probing pocket depth that further impaired plaque control and increased the risk of facial-lingual bone and attachment loss, and (3) the marked improvements in the soft tissues lateral to the root exposure, which allowed us to perform a predictable root-coverage technique with minimal discomfort for the patient. The reduction in the width of the gingival recession together with the marked improvement in the quality and quantity of the keratinized tissue lateral to the root exposure allowed for the use of a laterally moved, coronally advanced flap as the root-coverage surgical procedure ( Fig 7 ). This procedure combined the root coverage and the esthetic advantages of the coronally advanced flap with increases in gingival thickness and in the amount of keratinized tissue associated with the laterally moved flap. This surgical technique has been reported to be highly predictable when the adjacent tooth donor site has these specific characteristics of the gingival tissue: keratinized tissue width at least 6 mm greater than the width of the recession measured at the level of the cementoenamel junction, and keratinized tissue height at least 3 mm greater than the buccal probing pocket depth of the adjacent tooth. Whereas the width of keratinized tissue distal to the root exposure was more than adequate, the height (4 mm) was insufficient because of the 2-mm probing pocket depth at the level of the canine. This forced the periodontist to perform a modified approach of the laterally moved, coronally advanced flap in which the entire height of keratinized tissue distal to the defect was used for root coverage and a small (3 mm in the apical and coronal dimensions) and a thin (<1 mm) gingival graft was used to replace the keratinized tissue at the level of the tooth donor site ( Fig 7 , B ). Healing was uneventful at both the donor and receiving sites, and the patient’s postoperative course was completely painless. Six weeks after surgery, the orthodontic appliance was removed, and a lingual mandibular retainer, multibraided rectangular stainless steel wire, was bonded from canine to canine.