Dentists have an important role in preventing and detecting oral and systemic diseases because of their diagnostic and screening abilities and the frequency of patient visits. These skills and practice paradigms should be considered in solving the obesity epidemic. The well-described connection between periodontal disease and diabetes is a reason for dentists to intervene in the rise of obesity. Dentists are in a unique position to identify and aid in treatment of obstructive sleep apnea, a condition associated with obesity and diabetes. Dentists can play a role in raising awareness of overweight status and obesity risk behaviors in children.

- •

Dental professionals have an important role in the prevention and detection of many oral and systemic diseases because of their diagnostic and screening abilities, as well as the frequency of patient visits. These invaluable skills and practice paradigms should be considered as part of the equation to solve one of the largest public health concerns of our time: the obesity epidemic.

- •

There is a well-described connection between periodontal disease and diabetes, with implications that the relationship may be bi-directional. Periodontal disease and obesity are associated with inflammatory stress and increased production of proinflammatory cytokines. Clearly, these associations should be reasons for the dental profession to intervene in the rise of obesity.

- •

Insufficient sleep is another factor in the obesity problem and screening for sleep habits could be part of a comprehensive dental assessment, along with height, weight, blood pressure. The dental profession is in a unique position to identify and aid in the treatment of obstructive sleep apnea, a condition associated with obesity and diabetes.

- •

The rise of obesity and type 2 diabetes in children is of great concern and the dental profession can play a role in raising awareness of overweight status as well as obesity risk behaviors.

Introduction

Obesity is increasing at epidemic proportions in adults and in children on an international and national scale. The disturbing sequelae of this increased trajectory of overweight populations are the parallel increases in the chronic diseases that are comorbidities of obesity. According to the World Health Organization (WHO), overweight and obesity can be defined as an abnormal or excessive level of fat accumulation that may impair health. Like many chronic diseases, obesity has significant associated morbidity, mortality, and economic impact and is largely preventable. Primary health care providers, including dental professionals, are well-positioned to address this public health problem at the patient level. It is increasingly evident that the dental profession is a stakeholder in the weight status of its patients and can be part of a coordinated effort to prevent and intervene in the obesity problem.

Causes and factors associated with obesity

Having multifactorial causes, obesity is largely attributed to the systemic energy imbalance created by excessive caloric intake and inadequate levels of physical activity. Since the 1970s, diets have shifted toward processed foods, greater use of edible oils, and the increased popularity of sugar-sweetened beverages. Furthermore, the advent of new technologies has allowed for a markedly more sedentary lifestyle.

Some of the key factors associated with obesity risk include socioeconomic circumstances, minority status, geographic location, access to education, cultural beliefs, and genetic influences. Generally, obesity and overweight conditions disproportionately affect Hispanic, African American, multiracial, and low-income populations.

Causes and factors associated with obesity

Having multifactorial causes, obesity is largely attributed to the systemic energy imbalance created by excessive caloric intake and inadequate levels of physical activity. Since the 1970s, diets have shifted toward processed foods, greater use of edible oils, and the increased popularity of sugar-sweetened beverages. Furthermore, the advent of new technologies has allowed for a markedly more sedentary lifestyle.

Some of the key factors associated with obesity risk include socioeconomic circumstances, minority status, geographic location, access to education, cultural beliefs, and genetic influences. Generally, obesity and overweight conditions disproportionately affect Hispanic, African American, multiracial, and low-income populations.

Obesity indicators in adults and children

Body mass index (BMI) is a useful, but imperfect measure to classify a population into categories based on height and weight status. In adults, a BMI of greater than or equal to 25 is considered overweight, and that greater than or equal to 30 is obese. These values are scaled the same for all ages and both genders.

BMI percentiles are used to classify children. Values differ based on age and gender because the amount of body fat differs between males and females and changes with age. Overweight falls between the 85th and 94th percentile; obese are those greater than or equal to the 95th percentile.

Current statistics

International

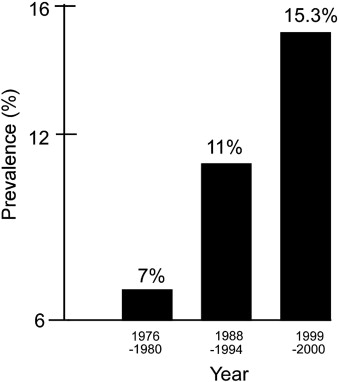

In 2010, WHO reported that approximately 43 million children younger than 5 were overweight, and that the distribution was no longer heavily skewed toward high-income countries. Nearly 35 million overweight children are living in parts of the developing world, and 8 million are in developed nations. The same report states that 65% of the world’s population lives in countries where overweight and obesity kill more people than underweight conditions. The onset of type 2 diabetes (T2DM) in young children has been falling in age and the prevalence of children ages 6 to 11 with T2DM had doubled in the past 20 years ( Fig. 1 ).

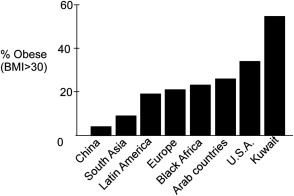

Internationally, it was estimated in 2008 that 1.5 billion adults, 20 and older, were overweight. Of these, over 200 million men and nearly 300 million women were obese. It was concluded that more than 1 in 10 of the global adult population is considered obese—a trend that has developed in the past decade. Fig. 2 display adult obesity (BMI >30) prevalence for selected countries around the world. Rates are rising rapidly, particularly in African regions, Arab countries, and the United States.

National Epidemic and Trends

Children

As of 2010, 18% of children ages 6 to 11 and 18.4% of adolescents 12 to 19 were considered obese in the United States. This correlates with an overall 54.5% increase in children, and a 63.6% increase in adolescents since 2000. Within the adolescent demographic, 13.9% meet the adult classification of obesity, with a BMI of 30 or greater.

The childhood obesity trend has been rapidly increasing since 1980 and prevalence has nearly tripled in 20 years. It is estimated that 30% of the young population in the United States will be obese by 2030. Furthermore, a study by Ritchie and colleagues found that a child who was overweight at any one point during the elementary school years was 25 times more likely to be overweight at age 12 than a child who was never previously overweight. It is predicted that 70% of overweight children will become obese adults with all the chronic disease implications attached, which underscores the importance of early intervention efforts.

Adults

National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) results from 2009 to 2010 found that more than one-third of adults were obese, and there were no significant differences found between genders. In addition, adults 60 years or older were more likely to be obese than younger adults. If the current trends continue, it is predicted that about 3 of 4 Americans will be overweight or obese by 2020.

Impact

Burden of Disease

Obesity has both physical and psychological complications. Physiologically, it increases the risk of T2DM, sleep apnea, orthopedic complications, certain cancers, periodontal disease (PD), high blood lipids, hypertension, and other cardiovascular risk factors. A recent study indicates that obesity may affect children before birth, linking maternal obesity and diabetes with autism spectrum disorder and developmental delays. Psychosocially, obesity may have a long-term negative impact, leaving the patient vulnerable to the development of depression, anxiety, social isolation, discrimination, a lower quality of life, and stigmatization. It has also been associated with unemployment, absenteeism, and the potential for lower wages in comparison with nonobese employees.

Medical Costs

According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, roughly $147 billion was devoted to obesity-related conditions in 2008. On average, the cost of health care for an obese individual exceeds that for a normal-weight person by $1429 per year.

Total medical costs related to this condition are projected to double every decade to account for 16% to 18% of total US health care expenditure by 2030. At this alarming rate, it is crucial for all health care providers to spread the message about the serious risks of obesity, and how it can be prevented with proper diet and lifestyle modifications.

The relationship between obesity and oral health

Depending on how one reads the literature today, one may think of the obese dental patient as an individual with an extra set of risk factors that should be appreciated during their dental care. Or, one may think of PD as a condition that substantially contributes to obesity and should be controlled rigorously in patients who are obese or are at risk for developing obesity.

The association between obesity and cardiovascular disease is well established. The association between PD and cardiovascular disease has also been extensively reviewed. Although the literature in these fields is beyond the scope of obesity management in the dental office, they form an important background for its consideration.

Periodontal disease

It has long been recognized that PD is more prevalent in patients with T2DM in whom obesity is a central attribute. In adults, PD is 3.1 times more likely to occur in overweight and 5.3 times more likely to occur in obese adults than in normal healthy weight adults and higher levels of the periodontal pathogen Tannerella forsythia was found more frequently in obese patients.

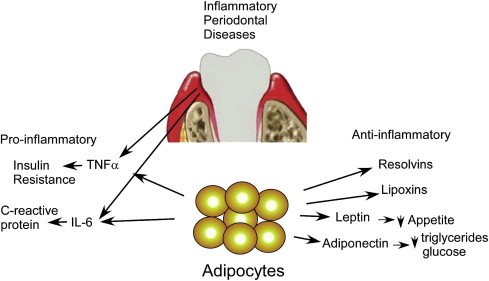

At a simplistic level, the adipocytes of fat tissue, which are surprisingly active in metabolic regulation, produce both anti-inflammatory and proinflammatory mediators ( Fig. 3 ). The inflammatory mediators released from PDs add to the adipocyte inflammatory mediators to enhance the systemic inflammatory state.

Periodontal therapy can reduce systemic inflammatory markers. For example, C-reactive protein (CRP) is reduced by periodontal treatment, which also has been shown to reduce serum levels of the proinflammatory cytokines leptin and interleukin-6. However, this effect is nullified by the production of these same cytokines by the large number of adipocytes in obese individuals.

Both diabetes and obesity are accentuated by PD. Thus, for example, blood levels of adiponectin, a hormone regulating glucose levels and fatty acid catabolism, are lower in patients with PD who also present with T2DM. Gingival crevicular fluid levels of the proinflammatory cytokine tumor necrosis factor-α increase with BMI, and metabolic syndrome has been shown to be more prevalent in patients with radiographic evidence of periodontal bone loss. Obesity also increases the risk of having PD. The generally proposed mechanism of this bilateral association is through their common ability to create oxidative (proinflammatory) stress.

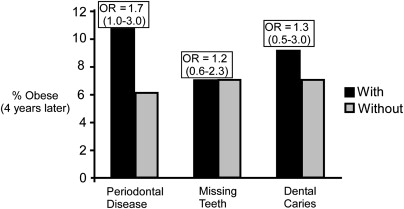

Upon acknowledging the common risk factors of obesity and PD, the question as to whether obesity causes PD or the converse has not been adequately answered. Almost all studies conducted are cross-sectional, for which one cannot determine the directionality of association. The possibility that PD contributes to obesity is suggested by a prospective study that indicates that obesity develops more frequently in patients with periodontal pockets. In this study, 1023 adults were selected who were not obese; 205 had periodontal pockets. Four years later, 22 (10.7%) of those who had pockets were obese as compared with 6.2% who did not have pockets. An odds ratio of 1.7 indicates that it is almost twice as likely to develop obesity if patients have PD at the outset. This difference approached statistical significance ( P = .056). A similar comparison with missing teeth and dental caries was clearly not significant. These data are summarized in Fig. 4 .

Both PD and obesity are associated with inflammatory stress and increased production of proinflammatory cytokines. Although an association seems to have been well established, there is no basis to recommend differences in dental treatment planning for obese patients but there is reason to think that the dentist should be ready to participate in a weight management program for the overweight dental patient who may be adversely affected by their oral disease condition.

Children

Although it seems that children with gingivitis may be affected in the same manner as adults with periodontitis, far less periodontal research has been conducted with children. In children, gingivitis occurs more frequently in obese children and is associated with insulin resistance. Salivary flow rate is decreased and dental caries is increased in obese children. Based on these observations, it appears that gingival inflammation may be the primary association between oral disease and obesity.

As previously noted, the incidence of child obesity has been escalating, and along with this trend is an increase in the prevalence of T2DM, as well as a lower age of onset. The same health behaviors affect adults and children: sedentary lifestyles and diets with excesses of fats and refined carbohydrates. These behaviors contribute to both obesity and T2DM. However, a link with obesity and dental caries has not been consistently found in studies (see section on caries and obesity).

Infectobesity

It is possible that oral bacteria could have an effect on development of obesity. An animal model for bacterial induction of obesity has been described. In this model, mice raised to be free of bacteria consume more food but gain less weight than their wild-type brothers and sisters who become fat. Differences in gastrointestinal bacterial composition have been described. Similarly, reports have appeared that indicate oral bacteria in obese individuals differ from those of healthy normal weight. It is appropriate to note that we all swallow about a gram (10 11 ) bacteria daily.

Sleep and obesity

Sleep duration has been increasingly recognized as factor related to weight gain in children as well as adults. In a study of 44,452 adults, those with sleep duration less than 6 hours were significantly more likely to meet metabolic syndrome criteria than those with longer sleep duration. Sleep duration has been related to elevated blood pressure by several investigators. There is sufficient evidence of association to the suggestion that sleep duration should be an important marker of cardiovascular disease. In an experiment in which healthy young men were sleep restricted for just 2 days, Spiegel and colleagues found decreased levels of the hormone leptin, which controls appetite, and a rise in plasma ghrelin levels, which increases appetite and favors the accumulation of lipids in visceral fatty tissue. In a more recent study of healthy individuals, Buxton and colleagues reported that short and disrupted sleep altered insulin levels and slowed metabolism to a rate that could add more than 12 pounds of weight in a year.

Obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) is associated with both obesity and diabetes, and a summary review of multiple studies suggests that weight loss can improve OSA with a positive effect on metabolic and cardiovascular risks. Among patients attending a diabetes obesity clinic, 58% had obstructive sleep apnea that was associated with worsening glycemic control. Children are also affected by OSA. Kohler and colleagues found that among adolescents, there was a 3.5-fold increase in OSA risk with each standard-deviation increase in BMI percentile. Studies have demonstrated a relationship between OSA, inflammation, and insulin resistance in obese as well as nonobese children.

Dentists can play an active role in identifying children and adults with possible OSA and referring them for assessment. Early detection, referral, and coordinated care with patients’ physicians can prevent additional consequences and improve quality of life. The increasing availability of oral appliances has resulted in more dentists becoming involved in the care of patients with sleep-related breathing disorders ; however, it is not clear if they are addressing weight status where appropriate.

Caries and obesity

Studies of the relationship between dental caries and BMI in children have not been conclusive. Most studies have not found a significant association between BMI for age and caries prevalence in primary or permanent dentition. However, Hilgers and colleagues, while confirming the lack of overall association, found that smooth surface caries increased significantly with BMI . There is evidence that overweight and obese children have accelerated dental development, which has implications for caries risk and orthodontic treatment.

Dental caries and sleep duration were significantly related in a pilot study of ninety 10-year-old Kuwaiti girls. Those who reported shorter weekday sleep duration had more decayed and filled teeth surfaces and also reported consuming more sugars in a dietary survey. Although multiple factors may contribute to this finding, one can speculate that the elevated levels of ghrelin that are associated with short sleep may contribute to sugar consumption.

A role for the dental profession

It has been demonstrated that specific repeated messages from multiple sources are more likely to promote behavioral change than single-source messages. Primary care physicians and pediatricians are well-equipped to address the obesity issue. The American Academy of Pediatrics recommends that health care providers should encourage healthy eating patterns and routine physical activity, and discourage TV and video time by providing families with education and anticipatory guidance. However, evidence suggests that busy providers do not adequately follow these recommendations. Several studies have found that the detection of obesity during routine medical appointments is low, and time constraints limit how much a clinician is willing or able to discuss with patients. Perrin and colleagues suggest that office-based tools targeting specific behaviors may be helpful. Dental professionals are in a good position to be able supplement and reinforce the information received in the medical setting, as well as to initiate the conversation. Tavares and Chomitz developed and tested the feasibility of a dental office–based tool for children, targeting obesity risk behaviors. The Healthy Weight Intervention , based on the concepts of Motivational Interviewing was designed for children of all weights and requires approximately 10 minutes during the routine hygiene visit. Using standard, evidence-based recommendations for improving obesity risks, this preventive intervention does not require specialized training.

The dental team is in a unique and favorable position to offer healthy weight intervention and obesity prevention. Most healthy patients visit a dentist more frequently than a physician on a yearly basis. Children and adolescents, in particular, follow the paradigm of annual medical and semiannual dental visits, potentially allowing for twice the annual frequency of any intervention. Additionally, it is already standard practice for dental professionals to promote dietary habits that avoid calorie and sugar-dense foods and beverages as caries prevention. They can easily expand their counseling to emphasize the implications of these dietary practices, in addition to the positive effects of physical activity and other lifestyle changes, on both oral and systemic health. For patients with suspected weight issues, the dentist can work alongside pediatricians, family physicians, and dietitians by providing referrals. Some dental settings, particularly pediatric dental practices, already measure weight and height for other purposes such as calculating dosages for local and general anesthesia. Obtaining BMI and BMI percentile measurements can be a feasible addition to the dental protocol, as it is noninvasive, and requires a small time commitment and minimal cost.

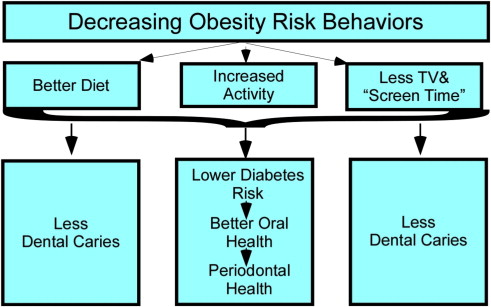

Accepting the premise that weight status is associated with oral health, weight screening, obesity prevention, and intervention in dental offices can be advocated as part of comprehensive dental assessment and treatment. As previously discussed in this article, there are strong links between obesity and oral health, particularly with respect to diabetes and PD. Decreasing obesity risks through diet and lifestyle changes can have a positive impact on oral as well as systemic health. It is important for the dental team to consider all the key domains of obesity risk behaviors, such as physical activity, screen time, and meal patterns; not only diet ( Fig. 5 ).