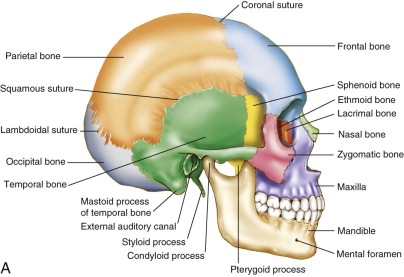

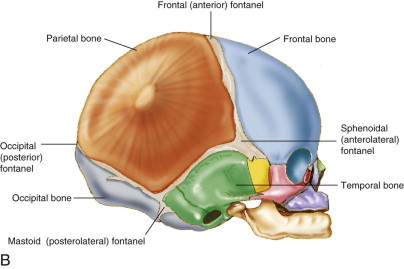

Craniosynostosis is a congenital defect resulting in the premature fusion of one or more cranial sutures. There are eight bones that make up the human cranium. In infancy, they are separated from each other by fibrous tissue junctions called sutures. Sutures undergo ossification during postnatal development and distinguish an adult from an infant skull ( Fig. 90-1 ). If sutures fuse prenatally, brain growth cannot occur perpendicular to the fused suture. Growth will occur parallel to the suture, causing a potential cosmetic and functional deterioration. Although craniosynostosis occurs in about 1 in 2000 live births, its etiology is still widely unknown. It has a similar prevalence to those affected with colorectal cancer (1 per 1,800) but is certainly not as well known to the general population, nor is its research as well funded. The sagittal suture is the most commonly involved cranial suture, followed by the coronal and the metopic. Lambdoid synostosis is the rarest.

Etiology

The mineralization of the cranial vault begins around 13 weeks’ gestation from several ossification centers. At around 18 weeks, the bone edges meet and sutures are induced. The suture is two plates of bone separated by a narrow space of immature, rapidly dividing osteogenic stem cells. Some of these differentiate to osteoblasts and create new bone. The skull initially enlarges by sutural expansion, with deposition of bone matrix along suture margins. This is particularly important during infancy, when the brain and skull grow exponentially, reaching 80% of adult size by 1 year of age. After this, the rate of skull growth significantly tapers off, the skull thickens, and the sutures become firmer with ossification. Skull growth continues but now relies on the much slower process of resorption and deposition that has been described by Enlow. At this point, the ongoing growth of the brain stimulates resorption of bone from the inner cortex of the cranium and deposition of bone to the outer cortex. When one or more sutures prematurely fuse, the harmonious patterns of skull growth change. These changes were described by Virchow in 1851. He suggested that skull growth is restricted in a plane perpendicular to the affected prematurely fused suture and compensates at the open sutures. Thus, growth occurs parallel to the closed suture. This theory persists today as the main one explaining the observed clinical changes.

It is believed that both genetic and environmental factors contribute to craniosynostosis. Abnormal mechanical forces have been suggested as a predisposing factor. Family history of associated anomalies suggests a genetic link. Over 100 syndromes have been described as associated with craniosynostosis. Many different mutations of six principal genes, MSX2, FGFR1, FGFR2, FGFR3, FBN1, and TWIST, have craniosynostosis as a primary clinical feature.

Diagnosis

Patients with craniosynostosis classically present with a misshapen head, which can easily be mistaken for simple deformational molding. Craniosynostosis is present at the time of birth. Because of the natural changes that occur in an infant’s craniofacial morphology during the first few months of life, the shape of the skull can appear to worsen with time. Deformational molding, on the other hand, will tend to improve with time. Because craniosynostosis is a true malformation of the skull, traditional treatments for deformational molding (including repositioning techniques and cranial molding appliances) will not be effective in true craniosynostosis.

The distinction of craniosynostosis from deformational molding is imperative. The diagnosis of craniosynostosis is usually a clinical one. Careful history, along with clinical examination by a competent practitioner, is usually satisfactory. Each type of suture closure causes a typical and recognizable cranial malformation. There have been many reports of misdiagnosis, which were unfortunately brought to light by the Wall Street Journal in 1996 after the Centers for Disease Control (CDC) was called out to investigate a 400% increase in incidence of craniosynostosis in the Colorado region. Many patients had unnecessary surgery, which led to the careful review and publication of the clinical differences between the two conditions by Huang et al.

Diagnosis

Patients with craniosynostosis classically present with a misshapen head, which can easily be mistaken for simple deformational molding. Craniosynostosis is present at the time of birth. Because of the natural changes that occur in an infant’s craniofacial morphology during the first few months of life, the shape of the skull can appear to worsen with time. Deformational molding, on the other hand, will tend to improve with time. Because craniosynostosis is a true malformation of the skull, traditional treatments for deformational molding (including repositioning techniques and cranial molding appliances) will not be effective in true craniosynostosis.

The distinction of craniosynostosis from deformational molding is imperative. The diagnosis of craniosynostosis is usually a clinical one. Careful history, along with clinical examination by a competent practitioner, is usually satisfactory. Each type of suture closure causes a typical and recognizable cranial malformation. There have been many reports of misdiagnosis, which were unfortunately brought to light by the Wall Street Journal in 1996 after the Centers for Disease Control (CDC) was called out to investigate a 400% increase in incidence of craniosynostosis in the Colorado region. Many patients had unnecessary surgery, which led to the careful review and publication of the clinical differences between the two conditions by Huang et al.

Craniosynostosis Syndromes

Metopic Craniosynostosis

Metopic synostosis typically causes a narrow forehead, bulging biparietal areas, a ridge over the metopic suture, and recessed lateral orbital rims. Patients can have apparent or true hypotelorism. Their overall cranial morphology is trigonocephalic. Up to a third of these patients will be syndromic, and many of these syndromic patients will have developmental delays.

Unicoronal Craniosynostosis

Patients with unicoronal synostosis typically develop a plagiocephalic cranial morphology. On the affected side, there is a flattened forehead, elevation of the supraorbital rim, widening of the palpebral fissure, a recessed lateral orbital rim, and deviation of the nasal radix toward the fused suture. The orbit on the involved side is small, and the globe is proptotic. The chin point can be deviated toward the opposite side, and the posterior cranial vault is rarely symmetrical due to compensatory changes. There is usually a palpable ridge over the fused suture.

Sagittal Craniosynostosis

Sagittal synostosis typically results in a scaphocephalic (keel-shaped) head. The bitemporal and biparietal dimensions are narrow, the forehead bossed, and the occipital region is prominent. There is sometimes an occipital shelf. A ridge is often palpable over the fused suture. These head shapes are most likely to be confused with the deformational molding that takes place in babies with prolonged hospital stays, for instance, premature infants.

Lambdoid Craniosynostosis

Lambdoid synostosis is quite rare—1 in 30,000 births. The presentation can be most difficult to distinguish from deformational molding, because the head shape typically is plagiocephalic. The vertical ear position from an occipital view reveals inferior displacement on the affected side. There may be a ridge over the fused suture and posterior displacement of the ear toward the ipsilateral side. The head shape from a vertex view has been described as trapezoidal. Often there is an associated head tilt. With positional plagiocephaly, the head shape is rhomboidal, or like a parallelogram.

Isolated squamosal, cranial base, or facial craniosynostosis are exceedingly rare. Red flags that should raise suspicion for craniosynostosis are enumerated in Box 90-1 .

- •

Misshapen head present at birth

- •

Early repositioning techniques do not improve the abnormal head shape

- •

Ridging over the suture

- •

Small, displaced, or absent fontanel

- •

Trapezoid head shape from vertex view

- •

Inferiorly displaced ear from occipital view

- •

Orbital involvement—wide palpebral fissure

- •

Other—abnormal bulges, facial asymmetry, associated with developmental delays, severity of case

Natural History

Because the fusion occurs prenatally, the abnormal cranial morphology is present at the time of birth. However, this can appear to worsen over the first several months as the baby grows, develops better tone, and begins to redistribute some of the initial deformational soft tissue changes that occur during the birthing process. The infant brain is rapidly expanding against this area of constriction where the fusion has occurred. This rapid expansion is the stimulus to the skull to grow and makes the deformation more obvious. If left untreated, negative neurologic consequences may develop. In general, single suture synostosis should not cause cerebral damage. This is a very difficult to study, and because of ethical dilemmas, many questions about this condition will likely never be answered. In 1982, Renier et al. published a landmark study describing placement of epidural pressure catheters in 92 patients with craniosynostosis. They found that 14% of patients with single suture craniosynostosis developed an elevation of intracranial pressure, compared with 42% of patients with multiple sutures involved. Increased intracranial pressure can lead to various neurologic compromises, such as developmental delays, headaches, irritability, behavioral changes, decreased vision, and cognitive delays. True symptoms related to increased intracranial pressure in patients with single-suture craniosynostosis have rarely been reported prior to the age of 1 and (in some cases) can reemerge after cranial vault expansion. These are often insidious findings, can be difficult to detect, and can be irreversible.

Hydrocephalus is not commonly associated with nonsyndromic single suture craniosynostosis, but may occur independently and not necessarily as a consequence of the condition. Ophthalmologic changes, however, can be a direct effect of craniosynostosis. Papilledema, optic nerve atrophy, loss of vision, exophthalmos, orbital dystopia, ptosis, strabismus, corneal erosions, or ulcers are all potential risks.

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses