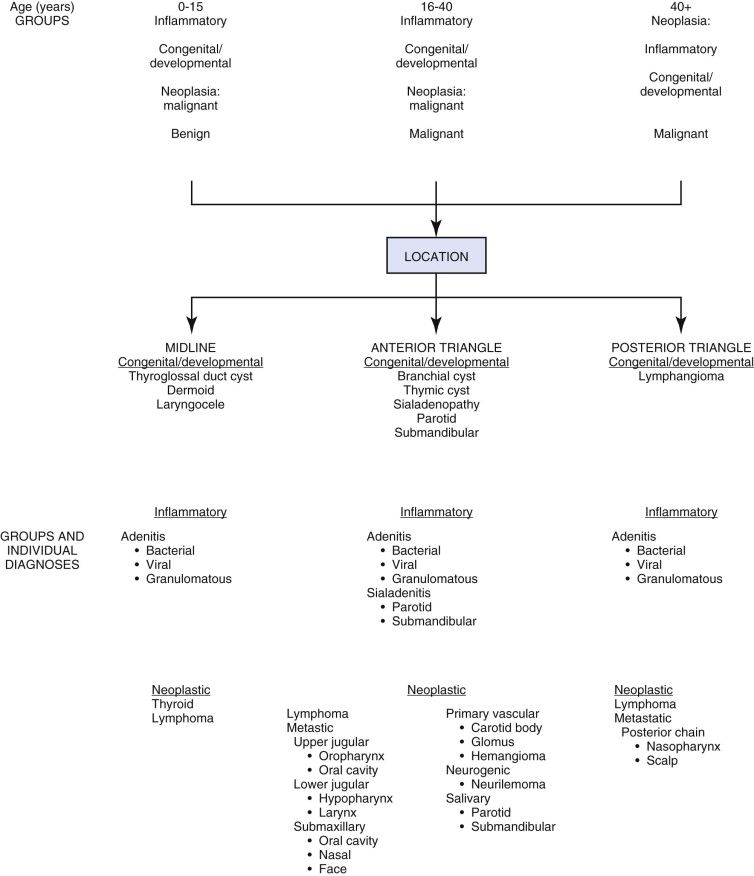

Oral and maxillofacial surgeons are frequently involved in the management of patients with neck masses. It is therefore important for such surgeons to have a clear understanding of the etiology, pathogenesis, diagnostic evaluation, and treatment of cervical masses. One of the most important factors that help define a specific diagnosis is the patient’s age. In general, three age groups need to be considered: pediatric (<15 years), young adults (16 to 40 years of age), and older adults (>40 years of age). Each of these age groups exhibits a certain relative frequency of disease occurrence, which can help the clinician develop an appropriate differential diagnosis ( Fig. 47-1 ).

It is important to note that the majority of neck masses in the young pediatric population are more commonly inflammatory and congenital rather than neoplastic. In young adults, the rate of neoplasia begins to increase along with a relative decrease in congenital lesions. In patients older than 40 years, neoplasia is always the primary consideration in those in whom a neck mass of unknown origin develops. The second important criterion in the diagnosis of a cervical mass is its location. Congenital, developmental, and traumatic neck masses are relatively consistent in their locations. Neoplasia, on the other hand, tends to vary in terms of anatomic location but is inclined to follow a systematic pattern of lymphatic spread from the primary oropharyngeal site. In 5% to 10% of patients, the primary source of the tumor is not readily apparent, and after a detailed, exhaustive physical examination coupled with imaging studies and directed biopsies of oropharyngeal tonsillar tissue, the pharyngeal walls, and the base of the tongue, approximately 1% to 2% remain carcinomas of unknown primary origin. This chapter outlines a practical approach to the diagnosis and evaluation of adult patients with cervical neck masses.

Diagnosis

History and Physical Examination

The most important aspect in diagnosing a cervical neck mass is an accurate and detailed history and physical examination. Every patient with a neck mass should undergo a thorough examination of the entire head and neck with a detailed review of the time of development of the mass along with associated symptoms and any history of trauma, irradiation, and previous surgery. When conducting a physical examination, it is imperative for all mucosal surfaces of the oropharynx to be examined directly or by indirect mirror or fiberoptic visualization and to obtain a tissue diagnosis in a timely and orderly fashion so that an accurate diagnosis can be made. This is particularly important when the suspicion of malignancy is high. Box 47-1 presents an algorithm for evaluation of a neck mass of unknown origin in an adult patient.

- 1

Thorough head and neck examination

- a

Direct and indirect visualization

- b

Digital palpation—neck and intraorally

- a

- 2

Fine-needle aspiration

- a

Diagnostic? Benign? Removal

- b

Non-specific?

- (1)

Repeat the head and neck examination

- (2)

Endoscopy with biopsy

- (+)

Diagnosis—treat based on the pathology

- (−)

Diagnosis—open biopsy of the mass

- (+)

- (1)

- c

Diagnostic? Malignant?

- (1)

Imaging study—computed tomography/magnetic resonance imaging/positron emission tomography

- (2)

Endoscopy with guided biopsy

- (+)

Malignancy—treat cancer

- (−)

Open biopsy

- (+)

- (1)

- a

Relevant Anatomy

Knowledge of the various lymphatic drainage routes within the head and neck allows the clinician to focus the examination and evaluation on specific oral mucosal sites within the head and neck ( Box 47-2 ). If the neck mass is unilateral, the primary lesion should be sought in the ipsilateral mucosa or cutaneous sites. If the neck mass is bilateral, it is likely to be in a midline structure such as the base of the tongue, supraglottic larynx, or nasopharynx. Another potential explanation is that bilateral cervical lymphadenopathy can occur when a lateral lesion crosses the midline and violates the lymphatics in the contralateral neck. With lymphadenopathy involving the supraclavicular space and the lower deep lateral cervical chain in the lower portion of the posterior triangle, the primary lesion is often not within the aerodigestive tract, and the search for the primary tumor should be broadened to include pulmonary, breast, and intra-abdominal sources.

-

Occipital nodes

-

Posterior scalp

-

-

Postauricular nodes

-

Posterior scalp

-

Mastoid

-

Posterior auricle

-

-

Extraglandular parotid nodes

-

Anterior scalp

-

-

Intraglandular parotid nodes

-

Anterior scalp

-

Temple

-

Cheek/mid-face

-

-

Retropharyngeal nodes

-

Posterior nasal cavity

-

Sphenoid and ethmoid sinuses

-

Hard palate

-

Soft palate

-

Nasopharynx

-

Posterior pharyngeal wall

-

-

Level I-A (submental)

-

Middle two thirds of the lower lip

-

Anterior gingiva

-

Anterior tongue

-

-

Level I-B (submandibular)

-

Ipsilateral lower and upper lip

-

Cheek

-

Nose

-

Medial canthus

-

Oral cavity to the anterior tonsillar pillar

-

-

Levels II-A and II-B (upper jugular nodes)

-

Oral cavity

-

Nasal cavity

-

Nasopharynx

-

Oropharynx

-

Hypopharynx

-

Larynx

-

Parotid gland

-

-

Level III (mid-jugular nodes)

-

Oral cavity

-

Oropharynx

-

Nasopharynx

-

Hypopharynx

-

Larynx

-

-

Level IV (lower jugular nodes)

-

Hypopharynx

-

Thyroid

-

Cervical esophagus

-

Larynx

-

-

Level V-A (posterior triangle)

-

Nasopharynx

-

Oropharynx

-

Skin of the posterior scalp and neck

-

-

Level V-B

-

Aerodigestive tract malignancies

-

Intra-abdominal metastasis

-

-

Level VI (anterior compartment delphian node)

-

Thyroid gland

-

Glottic and subglottic larynx

-

Piriform sinus

-

Cervical esophagus

-

Fine-needle aspiration (FNA) of the mass should be considered as the first-line diagnostic tool when appropriate cytologic assessment can be performed in a timely fashion by an experienced cytopathologist ( Fig. 47-2 ).

Imaging Studies

Computed tomography (CT) of the neck has now become the standard of care for evaluating neck masses and providing detailed anatomic data, as well as for the identification of occult primary tumors. The puff cheek and modified Valsalva techniques can help open opposed mucosal surfaces in the oral cavity, oropharynx, and hypopharynx and allow easier detection of known mucosal primaries. CT and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) have the highest specificity, 87% to 95%, for unknown primary head and neck tumors. The most common sites for the origin of the primary tumor are the palatine tonsil (35%), base of the tongue (26%), lung (17%), and nasopharynx (9%), followed by a host of other subsites such as the esophagus, skin, and larynx, which contribute between 1% and 4%. CT is helpful in delineating a cystic from a solid mass and can establish an accurate anatomic location within the neck when axial and coronal images are available. It is important to note that hypodensity within lymph nodes larger than 1.5 cm and loss of the traditional ovoid shape, as well as the presence of central areas of necrosis and nodal aggregation, are classic signs of metastatic carcinoma within a lymph node.

MRI provides information similar to that obtained with CT. However, it can provide more detailed soft tissue visualization of the neck. T2-weighted images and fat suppression techniques have been helpful in looking for early mucosal disease as a cause of metastatic neck masses of unknown primary cause, particularly for detailed evaluation of the base of the tongue or the sinonasal tract.

Ultrasonography is useful for localization of a neck mass and differentiation of cystic from solid masses and is particularly helpful in differentiating congenital cysts from solid lymph nodes, glandular tumors, or vascular lesions. Ultrasound may also be used as an image guidance technique for needle aspiration or core biopsy procedures.

Chest radiographs (posterior, anterior, and lateral views) allow the clinician to screen for primary lung neoplasms or lung metastases from primary head and neck malignancy or for the presence of mediastinal adenopathy.

If a suspicious lesion is found on chest radiography, further investigation with CT of the chest is appropriate. Plain chest radiography has a specificity and sensitivity of 73% and 80%, respectively, for evaluating pulmonary metastasis in patients with head and neck tumors.

Positron emission tomography (PET) with F-fluorodeoxyglucose is able to identify areas of hypermetabolism within the head and neck and is sensitive to lesions larger than 6 mm. Though not currently standard therapy for the evaluation of head and neck cancer, PET is increasingly being used for disease surveillance and also for evaluation of patients with known primary head and neck tumors. PET is routinely becoming used for the evaluation of patients with occult primary tumors of the head and neck. The sensitivity and specificity of PET are reported in some studies to be 100% and 94%, respectively. Positive and negative predictive values are 88.8% and 76.5%, respectively. Newer technologies are now able to fuse the PET scan with the CT scan to further delineate the lesions. Waldeyer’s ring is often difficult to interpret because of physiologic uptake in overlying structures such as lymphoid tissue and salivary glands.

Pan-Endoscopy

Pan-endoscopy of the head and neck is an important diagnostic modality used to detect an occult primary mucosal lesion, as well as to identify synchronous primary tumors within the aerodigestive tract. The procedure begins with nasal endoscopy using a zero-degree rigid endoscope to examine the nasopharynx. Random, generous biopsy specimens are taken from the nasopharynx and subjected to histologic examination, which may include frozen section. Should this specimen be positive for a malignant process, the procedure is aborted because definitive treatment of nasopharyngeal carcinoma is radiation therapy and chemotherapy. If the results from the nasopharyngeal frozen section are negative, the evaluation is advanced to examination and sampling of the oral cavity, oropharynx, hypopharynx, and larynx, along with inspection, palpation, and directed biopsy of the base of the tongue, tonsillar fossa, and posterior pharyngeal wall.

Controversy exists regarding the most appropriate mechanism for sampling the tonsil. This can include direct sampling of the tonsillar fossa or tonsillectomy to eliminate sampling error. Koch and associates reported a 10% rate of spread of metastatic carcinoma from a contralateral tonsil and therefore recommended bilateral tonsillectomy. Bilateral tonsillectomy, however, is typically reserved for patients with bilateral metastatic cervical lymphadenopathy. Once this is completed, rigid cervical esophagoscopy and bronchoscopy can be performed for evaluation of the remainder of the aerodigestive systems.

Relevant Anatomy

Knowledge of the various lymphatic drainage routes within the head and neck allows the clinician to focus the examination and evaluation on specific oral mucosal sites within the head and neck ( Box 47-2 ). If the neck mass is unilateral, the primary lesion should be sought in the ipsilateral mucosa or cutaneous sites. If the neck mass is bilateral, it is likely to be in a midline structure such as the base of the tongue, supraglottic larynx, or nasopharynx. Another potential explanation is that bilateral cervical lymphadenopathy can occur when a lateral lesion crosses the midline and violates the lymphatics in the contralateral neck. With lymphadenopathy involving the supraclavicular space and the lower deep lateral cervical chain in the lower portion of the posterior triangle, the primary lesion is often not within the aerodigestive tract, and the search for the primary tumor should be broadened to include pulmonary, breast, and intra-abdominal sources.

-

Occipital nodes

-

Posterior scalp

-

-

Postauricular nodes

-

Posterior scalp

-

Mastoid

-

Posterior auricle

-

-

Extraglandular parotid nodes

-

Anterior scalp

-

-

Intraglandular parotid nodes

-

Anterior scalp

-

Temple

-

Cheek/mid-face

-

-

Retropharyngeal nodes

-

Posterior nasal cavity

-

Sphenoid and ethmoid sinuses

-

Hard palate

-

Soft palate

-

Nasopharynx

-

Posterior pharyngeal wall

-

-

Level I-A (submental)

-

Middle two thirds of the lower lip

-

Anterior gingiva

-

Anterior tongue

-

-

Level I-B (submandibular)

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses