Humans recognize each other by the shape of the eyes and the middle third of the face. For this reason, successful repair of the naso-orbito-ethmoid (NOE) region is difficult, and even minor shortcomings in the final result are recognizable to others. In addition, the NOE area contains several types of specialized tissues (bone, cartilage, sinus, tendon, and lacrimal and ocular tissues) and distinctive architectures that, once lost, are difficult for the surgeon to restore. The bone in this area is distinctly shaped, difficult to access, and covered by the thinnest soft tissue in the face.

A post-traumatic NOE deformity can have three key components: diminished nasal projection, increased intercanthal distance (telecanthus), and impaired nasofrontal or lacrimal drainage. The best outcomes following significant NOE injury are the result of accurate diagnosis and treatment of these three components.

Etiopathogenesis/Causative Factors

The etiology of NOE trauma differs from that of mandibular and nasal trauma. NOE injuries are the result of focused high-energy transfer to the intercanthal area. A motor vehicle accident is, for example, a more likely cause than interpersonal violence. The trauma surgeon should always remember that NOE injury is the result of significant energy transfer and that patients who have sustained considerable NOE trauma will often have associated cervical spine, ocular, or intracranial injuries.

Pathologic Anatomy and Examination

The foundation of the NOE region is a paired set of midline facial buttresses that flow vertically from the piriform rim up to the frontal bar; these buttresses support nasal projection and attachment of the medial canthal tendon (MCT).

Medial Canthal Tendon

It is helpful to conceptualize the MCT as the medial extent of a tarsal apparatus. The tarsal apparatus runs in the plane of the orbital septum and extends from the lateral canthus at Whitnall’s tubercle, through the upper and lower tarsi, and into the MCT, where it attaches to the frontal process of the maxilla. The tarsal apparatus provides support to the eyelids and defines the normal almond shape of the palpebral fissure.

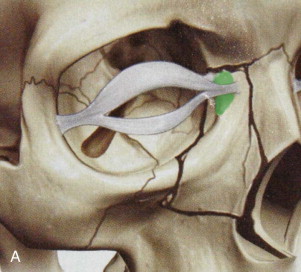

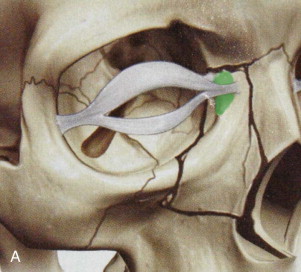

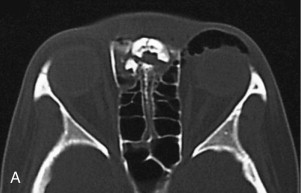

Before attaching to the frontal process of the maxilla, the MCT splits into anterior and posterior components, with the lacrimal sac between them. The superficial component attaches broadly to the anterior lacrimal crest, whereas the deep component of the MCT attaches along the posterior lacrimal crest. Restoration of this deep component after canthal detachment is critical for maintaining the proper shape and appearance of the eyelids; it rounds the eyelids against the medial aspect of the globe, thereby allowing normal lid function. When the MCT is repaired, its deep direction of attachment must be restored. The posterior component is also associated with a slip of orbicularis oculi called Horner’s muscle; when Horner’s muscle contracts, it assists movement of fluid through the lacrimal system ( Fig. 42-1 ).

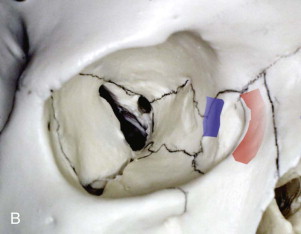

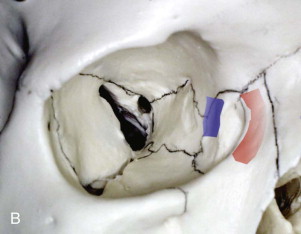

Direct blunt force to the NOE region buckles the medial orbital walls and fragments the thin nasal, lacrimal, ethmoid, and frontal bones. The nasal root can also telescope posteriorly into the ethmoid air cells as a single unit, lodge under the nasal process of the frontal bone, and obstruct nasofrontal outflow of the frontal sinus ( Fig. 42-2 ). Frequently, NOE injury will be accompanied by an increased intercanthal distance (telecanthus) resulting from widening of the canthal-bearing bones, MCT detachment, or both.

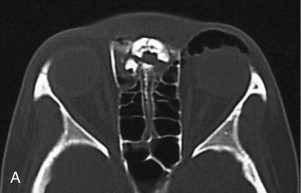

A thorough examination will distinguish NOE injuries from an isolated nasal fracture. NOE injury has a distinctive appearance: a horizontally widened intercanthal region along with a vertically shortened nose that is flattened and widened with an upturned nasal tip. The deformity has a remarkably consistent appearance in patients ( Fig. 42-3 ).

Pathologic Anatomy and Examination

The foundation of the NOE region is a paired set of midline facial buttresses that flow vertically from the piriform rim up to the frontal bar; these buttresses support nasal projection and attachment of the medial canthal tendon (MCT).

Medial Canthal Tendon

It is helpful to conceptualize the MCT as the medial extent of a tarsal apparatus. The tarsal apparatus runs in the plane of the orbital septum and extends from the lateral canthus at Whitnall’s tubercle, through the upper and lower tarsi, and into the MCT, where it attaches to the frontal process of the maxilla. The tarsal apparatus provides support to the eyelids and defines the normal almond shape of the palpebral fissure.

Before attaching to the frontal process of the maxilla, the MCT splits into anterior and posterior components, with the lacrimal sac between them. The superficial component attaches broadly to the anterior lacrimal crest, whereas the deep component of the MCT attaches along the posterior lacrimal crest. Restoration of this deep component after canthal detachment is critical for maintaining the proper shape and appearance of the eyelids; it rounds the eyelids against the medial aspect of the globe, thereby allowing normal lid function. When the MCT is repaired, its deep direction of attachment must be restored. The posterior component is also associated with a slip of orbicularis oculi called Horner’s muscle; when Horner’s muscle contracts, it assists movement of fluid through the lacrimal system ( Fig. 42-1 ).

Direct blunt force to the NOE region buckles the medial orbital walls and fragments the thin nasal, lacrimal, ethmoid, and frontal bones. The nasal root can also telescope posteriorly into the ethmoid air cells as a single unit, lodge under the nasal process of the frontal bone, and obstruct nasofrontal outflow of the frontal sinus ( Fig. 42-2 ). Frequently, NOE injury will be accompanied by an increased intercanthal distance (telecanthus) resulting from widening of the canthal-bearing bones, MCT detachment, or both.

A thorough examination will distinguish NOE injuries from an isolated nasal fracture. NOE injury has a distinctive appearance: a horizontally widened intercanthal region along with a vertically shortened nose that is flattened and widened with an upturned nasal tip. The deformity has a remarkably consistent appearance in patients ( Fig. 42-3 ).

Clinical and Radiographic Assessment

Thorough digital NOE examination for mobility, crepitus, and depressibility often yields the most information about the extent of NOE injury. The entire nose—or portions of it—may be digitally depressible. Formal preoperative ophthalmology consultation should be considered for a patient who has sustained enough force to fracture the orbital walls. Occult ocular injury may be present.

The status of the MCT attachment to bone can be assessed clinically by the “bowstring” test ( Fig. 42-4 ): the lateral canthus is grasped and displaced laterally while observing and palpating the medial canthal area. Lateral displacement of the medial canthal area suggests a compromised bony attachment. This test can be difficult to interpret accurately, especially in the presence of acute edema and a conscious patient.

In the operating room, the status of the MCT can be assessed by placing an instrument in the nose under the bony MCT attachment while simultaneously palpating the area from the outside; manipulation of the instrument will help one understand the status of the MCT-bearing bone fragment.

Diagnosis

Classification of Naso-Orbito-Ethmoid Fractures

Even though NOE trauma rarely resembles textbook diagrams, classifying the injury enhances both communication and treatment planning. The most widely used and therefore useful NOE injury classification scheme remains that developed by Markowitz and colleagues. The status of the MCT, the canthal-bearing bone fragment, and the fracture pattern define a clinically useful classification system ( Fig. 42-5 ). From type I to type III, the energy sustained from the injury increases.

- •

Type I: single-segment central fragment

- •

Type II: comminuted central fragment with fractures remaining external to the insertion of the MCT

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses