Demographic changes over the coming decades will heighten the challenges to both the dental profession and the nation. The expected growth in the numbers of racial and ethnic minorities and the concomitant growth of immigrant populations are likely to lead to worsening of oral health disparities. Their consequences are becoming increasingly evident, as the profession strives to improve the oral health of all Americans. The increasing diversity of the population, together with the importance of cultural beliefs and behaviors that affect health outcomes, will require ways to enhance provider-patient communications and oral health literacy. One important means by which to promote oral health in diverse populations is to develop a dental workforce that is both culturally and linguistically competent, as well as one that is as culturally diverse as the American population.

Demographic changes in American society will have increasingly important effects on the oral health of the nation and on the practice of dentistry. As the French philosopher Auguste Comte (1798–1857) stated, “Demography is destiny.” One much discussed demographic trend affecting dentistry is the “graying” of America. According to the United States Census Bureau estimates, by the year 2030 over 20% of Americans will be 65 and older . One consequence of this trend is that in 25 years most of America will appear demographically much like Florida does today. Overall, the number of Americans 65 years or older will double over the coming 35 years, reaching 80 million by the year 2045. The impact on dental practice resulting from these growing numbers of elders has become well recognized.

However, an equally if not more significant demographic trend, but one much less discussed in the context of dental practice, is the dramatic growth in the numbers of Americans from racial and ethnic minority groups. Presently, United States Census statistics show that over 30% of Americans are minorities (ie, Hispanic, African American, Asian, Native American), with Hispanics being the largest of these groups . By 2010, the numbers of minorities are expected to increase to 35%, and by 2025 to approach 40% of the United States population. Another, and related, major demographic trend that also has yet to receive adequate attention in the context of dental practice is the growth in immigration to America.

From 1990 to 2000 the number of immigrants in the United States increased by 50%, from 20 million to over 30 million. Currently, over 11% of the United States population is foreign-born (over 52% of them are from Latin America and over 26% from Asia). Immigrants represent an even greater proportion of the population in the nation’s two largest states: over 20% of California and over 16% of New York. However, the effects of immigration are evident throughout the country; for example, the number of foreign-born in North Carolina, Georgia, and Nevada grew by 200% or more in the past decade. Furthermore, the growth of the foreign-born population segment is expected to accelerate.

The social, political, and economic pressures on the dental profession to meet the health needs of an increasingly diverse society will only grow over the coming decades. It is important to note that within the practicing lifetimes of many current dentists—and certainly of current dental students—the number of persons in our nation who are members of minority groups will exceed the numbers of non-Hispanic Whites in the United States. Our successes as a profession in meeting such challenges are in large part dependent on adequately addressing the multicultural issues that affect doctor-patient communications and patients’ health beliefs and attitudes. This is a major field of research activity that is briefly reviewed in this article, with the goal of identifying ways that may enable current and future dental practitioners to become better prepared to meet the needs of such diverse patient populations.

Health disparities and the multicultural imperative

Health disparities are well documented in minority populations, such as African Americans, Hispanics, American Indians, Alaska Natives, and other racial and ethnic minority groups. Individuals in these groups bear a disproportionate burden of disease and disability, and these disparities result in “lower life expectancy, decreased quality of life, loss of economic opportunities, and perceptions of injustice” . In their report addressing ethnic and racial disparities in medical care, Betancourt and colleagues noted that the lack of diversity in both the health care workforce and its leadership has resulted in policies, procedures, and delivery systems that are incapable of serving diverse populations. One simple example includes clinic hours that did not accommodate work schedules, long waiting times to make appointments, and complicated bureaucratic processes. Unequal Treatment: A Report of the Institute of Medicine documented the existence of disparities in health care, even when there is equal access to care, and provided evidence of cultural differences in health care between minorities and nonminorities. These differences were also related to disparities in access, health status, and health outcomes . The first United States National Health Care Disparities Report, issued by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, presented a comprehensive national overview of disparities, including disparities in oral health, and in access to health care services and insurance, health outcomes, and the quality of care among United States racial, ethnic, and socioeconomic groups .

A major determinant of oral health disparities is limited access to dental care, both preventive and restorative, and a major barrier to dental care access is lack of dental insurance, in particular private dental coverage . While dental insurance may be an essential prerequisite for ensuring access to care, it may be insufficient by itself for eliminating oral health disparities, as there exist other important determinants of oral health status and dental care access. These may include issues related to doctor-patient communications, including cultural and linguistic competency of care providers and the health beliefs and health literacy of patients .

Cultural competence in health care may be defined as an understanding of the importance of social and cultural influences on patients’ health beliefs and behaviors; considering how these factors interact at multiple levels of the health care delivery system; and, finally, devising interventions that take these issues into account to assure quality health care delivery to diverse patient populations. Inconsistent patient behaviors and attitudes related to compliance with treatment regimens is often a result of cultural conflict between minority patients and their providers. Clinical inexperience in interacting with minority patients and beliefs held by the provider about the behavior or health of minorities may contribute to a cultural dissonance between providers and patients. Additionally, time and resource constraints imposed on clinic visits may result in providers making snap judgments based on prototypes or stereotypic decision-making models when diagnosing and treating patients. Overlooking patients’ cultural beliefs may foster a lack of trust in the provider and their diagnoses, and decrease the likelihood that a person will comply with the prescribed treatment.

A related consideration in ensuring appropriate access to culturally competent health care providers is the discordance on the race and ethnicity of patients and providers and the maldistribution of culturally competent providers. A review by the Sullivan Commission’s Report on Health Professions Diversity showed that minority patients in the United States have higher levels of satisfaction in race- or ethnicity-concordant settings . In a study among the Hispanic population, Flores reported that it was very important to Hispanics to have a physician who speaks Spanish and fully understands Hispanics’ cultural values. In a recent study of a Canadian-Asian community, Wang found low accessibility to medical care providers in areas heavily populated by Chinese immigrants. He concluded that such a maldistribution was especially concerning because of the “overwhelmingly strong preference of Chinese immigrants for ethnically and dialectically matched family physicians” .

Perceived discrimination affects satisfaction with care and care-seeking behaviors. Such significant effects have also been observed in populations in other countries. In a study of access to medical treatment in Sweden, Wamala and colleagues found that perceived discrimination and socioeconomic disadvantage were each independently associated with refraining from use of care. Such perceptions may not only affect patients’ care seeking, but may also influence dentists’ behaviors. In a study from Brazil, Cabral and colleagues found that a patient’s race significantly affects dentists’ decision-making as to whether to extract or retain a decayed tooth.

Doctor-patient communication may play a major role, as there may be difficulties in communication, particularly in non-English-speaking patients, and in the case of a dentist’s or hygienist’s inability to speak the patient’s native language. But, even among persons of one language group, Spanish, there exist significant variations and Hispanics serve as an example of the complex challenges we face, combining issues of both culture and language, in meeting the needs of both “new Americans” as well as of those who are multigenerational Americans.

Cultural competence is intimately related to health literacy . The American Dental Association (ADA) defines oral health literacy as “the degree to which individuals have the capacity to obtain, process, and understand basic health information and services needed to make appropriate oral health decisions.” Importantly, effective communication is dependent on both the oral health literacy of patients as well as the skills, preferences, and expectations of oral health care providers. Health literacy is thoroughly discussed in the article by Dr. Horowitz elsewhere in this issue.

Health behaviors, culture, and oral health

The World Health Organization Constitution presented a holistic definition of health as “a state of complete physical, mental, and social well-being, and not merely the absence of disease or infirmity.” From this perspective, the roles and responsibilities of health care professionals go beyond the biologic and technologic sciences, and enter the sociocultural and behavioral domains of health promotion. Patients’ individual preferences and behavioral risk factors are intimately related to their sociodemographic and cultural backgrounds. The resulting oral health beliefs held by patients, and their related risk behaviors, are intimately related to patients’ health-related risk behaviors, receptivity to change, and ultimately on patients’ health outcomes. To systematically understand oral health outcomes and to design effective oral health interventions, a variety of theoretic frameworks and conceptual models drawn from psychology and social science have been applied to dentistry. For example, Barker has applied the health belief model (HBM) to the analysis of compliance with preventive dental behaviors. The HBM states “that for individuals to follow prescribed advice they must believe that they are susceptible to the disease (‘susceptibility’), that the disease is serious (‘seriousness’), and that the benefits of following prescribed advice outweigh costs (‘benefits’)” . Using the HBM, she found that the health beliefs of susceptibility and benefits were significantly related to compliance with preventive dental advice.

It has also been found that oral health risk behaviors may not be modifiable by oral health educational interventions, if such interventions are not framed in a culturally informed and sensitive manner. Nakazono and colleagues used data from the International Collaborative Study of Oral Health Outcomes II USA study to examine oral health beliefs in diverse populations, developing oral health belief measures that corresponded to the HBM dimensions. They found that both age and race-ethnicity were significant predictors of the perceived benefits of preventive practices, with White adults “more likely to believe in the benefit of preventive practices” . Kiyak and colleagues , in their study of ethnicity and oral health in older adults, observed that non-White elders tended to have less confidence in their ability to control their oral health. In addition, those elders in their study who were immigrants (primarily the Asian and Hispanic elders) also reported less concern about the value of healthy teeth or “even about saving their natural teeth” .

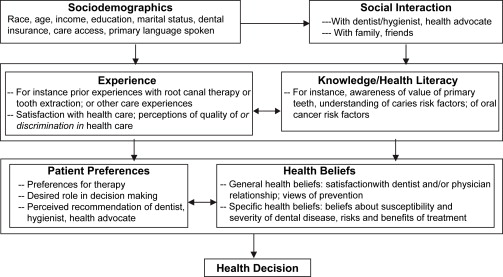

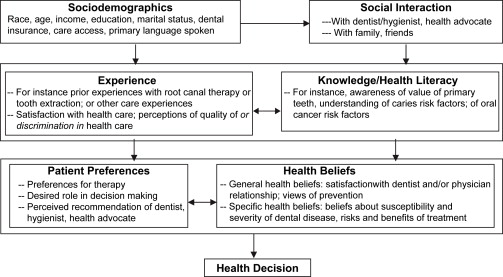

In the authors’ own work, the health decision model serves as a useful means by which to conceptualize the interplay of multiple factors ( Fig. 1 ) that affect oral health, including health beliefs. The health decision model is a conceptualization of factors leading to individuals’ health decisions and includes a number of potential influences on health decisions, such as health beliefs, individual preferences and knowledge, prior experiences, and social interactions (such as with physicians and family). The application of such a model may serve to guide the design and implementation of health promotion efforts aimed at improving health outcomes in diverse and multicultural populations. For example, it has been found that patients who are more involved in the decisions regarding their treatment have better subsequent health outcomes.

As described by Eraker and colleagues , there is not a prespecified causal ordering of factors influencing health decisions. Rather, each of the domains of health beliefs, patient preferences, experience, and knowledge influence one another, and are affected by social interaction and sociodemographic factors as well. Cultural factors, for example such as those related to race, ethnicity, and national origin, will affect each of these domains in variable ways. Thus, the health decision model is not intended to serve as a causal guide for the relationship among these elements, but may instead be used as an organizing framework to design culturally appropriate interventions, as well as to create oral health education and promotion materials that respect cultural beliefs. The materials that are developed may then serve to elevate the oral health literacy of the target population and serve as community resources, patient self-management, and decision support tools.

However, as a “one-size-fits-all” approach will not be maximally effective in multicultural populations, the development of all interventions and materials will most likely need to be adapted and customized to fit the particularities of each cultural group. Thus, while the health decision model has provided a useful framework for much of the authors’ work, when it comes to the implementation of a targeted intervention in a culturally diverse setting, the authors have found the chronic care model (CCM) to be a highly relevant conceptual model for implementation and evaluation of interventions in multicultural settings, as described below.

Health behaviors, culture, and oral health

The World Health Organization Constitution presented a holistic definition of health as “a state of complete physical, mental, and social well-being, and not merely the absence of disease or infirmity.” From this perspective, the roles and responsibilities of health care professionals go beyond the biologic and technologic sciences, and enter the sociocultural and behavioral domains of health promotion. Patients’ individual preferences and behavioral risk factors are intimately related to their sociodemographic and cultural backgrounds. The resulting oral health beliefs held by patients, and their related risk behaviors, are intimately related to patients’ health-related risk behaviors, receptivity to change, and ultimately on patients’ health outcomes. To systematically understand oral health outcomes and to design effective oral health interventions, a variety of theoretic frameworks and conceptual models drawn from psychology and social science have been applied to dentistry. For example, Barker has applied the health belief model (HBM) to the analysis of compliance with preventive dental behaviors. The HBM states “that for individuals to follow prescribed advice they must believe that they are susceptible to the disease (‘susceptibility’), that the disease is serious (‘seriousness’), and that the benefits of following prescribed advice outweigh costs (‘benefits’)” . Using the HBM, she found that the health beliefs of susceptibility and benefits were significantly related to compliance with preventive dental advice.

It has also been found that oral health risk behaviors may not be modifiable by oral health educational interventions, if such interventions are not framed in a culturally informed and sensitive manner. Nakazono and colleagues used data from the International Collaborative Study of Oral Health Outcomes II USA study to examine oral health beliefs in diverse populations, developing oral health belief measures that corresponded to the HBM dimensions. They found that both age and race-ethnicity were significant predictors of the perceived benefits of preventive practices, with White adults “more likely to believe in the benefit of preventive practices” . Kiyak and colleagues , in their study of ethnicity and oral health in older adults, observed that non-White elders tended to have less confidence in their ability to control their oral health. In addition, those elders in their study who were immigrants (primarily the Asian and Hispanic elders) also reported less concern about the value of healthy teeth or “even about saving their natural teeth” .

In the authors’ own work, the health decision model serves as a useful means by which to conceptualize the interplay of multiple factors ( Fig. 1 ) that affect oral health, including health beliefs. The health decision model is a conceptualization of factors leading to individuals’ health decisions and includes a number of potential influences on health decisions, such as health beliefs, individual preferences and knowledge, prior experiences, and social interactions (such as with physicians and family). The application of such a model may serve to guide the design and implementation of health promotion efforts aimed at improving health outcomes in diverse and multicultural populations. For example, it has been found that patients who are more involved in the decisions regarding their treatment have better subsequent health outcomes.