A 13-year-old sought treatment for a severely compromised maxillary left central incisor and an impacted fully developed left canine. Extraction of both teeth became necessary. As the key component of the revised comprehensive treatment plan, the right maxillary central incisor was moved into the position of the left central incisor. All other maxillary teeth were moved mesially to close any gaps. Active orthodontic treatment was completed after 34 months. Frenectomy, minor periodontal surgeries, and bonded lingual retainers were used to improve aesthetics and stabilize the tooth positions. The patient was pleased with the treatment outcome. Cone-beam computed tomography provided evidence that the tooth movement was accompanied by a deviation of the most anterior portion of the median palatine suture. This observation may make relapse more likely if long-term retention cannot be ensured. Root resorption was not observed as a consequence of the major tooth movement.

Moving an incisor to the contralateral side is a rarely used orthodontic procedure. Only a few cases have been reported in the literature. Two reports suggested a higher relapse tendency than for other types of tooth movement, but the long-term outcome of the procedure remains to be assessed in controlled clinical studies. All published cases with midline crossing were initiated during the mixed dentition and treatment was completed at approximately 12 years of age.

Follin et al used Beagle dogs to investigate the movement of incisors as a function of animal age and median palatal suture (MPS) closure. In their study, the movement of the tooth appeared to be faster in old animals, but there was a much higher degree of root resorption. In addition, histology suggested differences among the tooth movements that were related to the status of MPS closure. In young animals the suture was dislocated in front of the test tooth, whereas in old animals with closed MPS the tooth moved across the MPS.

Thus, the feasibility of relocating a maxillary central incisor across the midline has been demonstrated previously. However, to the best of our knowledge, no case has been documented showing this type of tooth movement in the permanent dentition of an adolescent patient. The present case report demonstrates the feasibility of closing a wide gap in the aesthetic zone by bilateral shifting of several teeth mesially, in particular a central incisor that was moved across the midline. At treatment completion, cone-beam computed tomography (CBCT) was used to show the relative position of the relocated incisor, the incisive foramen, the nasopalatine canal, and the MPS. In addition, the presence or absence of root resorption was investigated.

Diagnosis and etiology

A 13-year-old Brazilian boy visited the orthodontic clinic because he had “one missing tooth, and the other teeth were too far forward.” He suffered a bicycle accident when he was 8 years old, receiving minor facial bruises. The accident traumatized the maxillary left central incisor, requiring partial pulpotomy. He had a thumb-sucking habit until age 2 years. He did not report any other dental or medical problems, nor was he taking any medication. One week prior to the orthodontic consultation, he saw a general dentist and no caries were diagnosed. At the initial examination and throughout treatment, he maintained good oral hygiene.

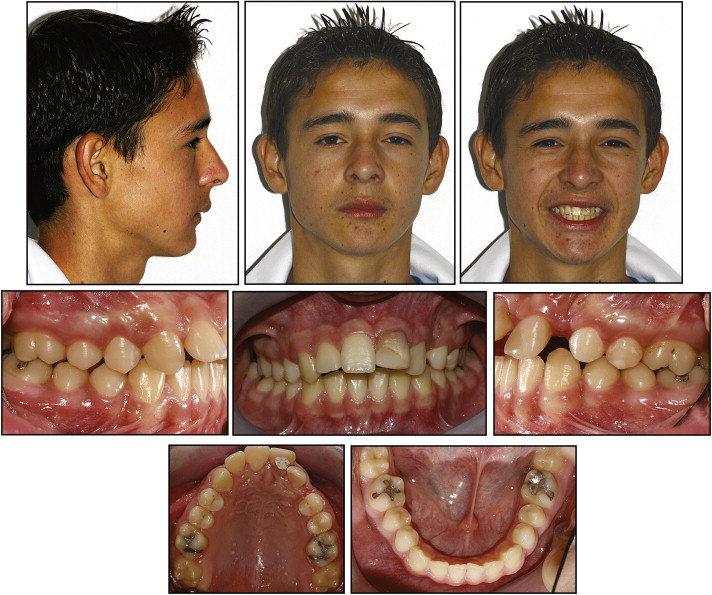

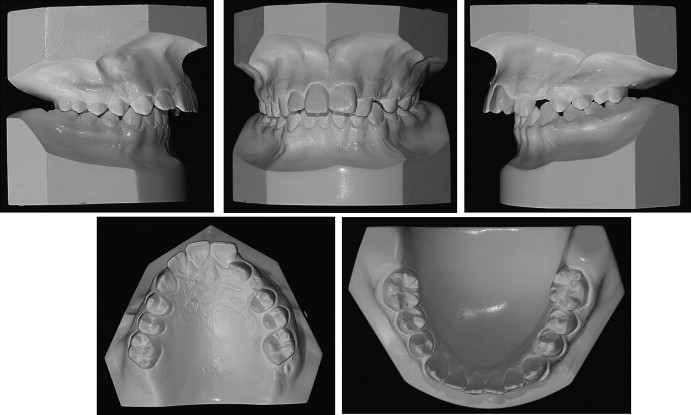

At the first orthodontic examination, the patient had a convex soft tissue profile with a retrognathic mandible ( Figs 1-4 ). The nasolabial angle was normal to obtuse, and the lower lip was retrusive to Rickett’s E plane. From the frontal view, his face was slightly asymmetrical, with the right side being a little longer than the left side. When smiling, the patient presented uneven gingival margin levels. The incisal edges also were not level. The crown of the injured left central incisor was shorter than the right one. Intraoral and dental cast examinations showed a molar full-cusp angle Class II on the right and left. The right canine was also in a Class II relationship. The left maxillary canine had not yet erupted. An overjet of 11 mm was measured and, as a result of the overjet, the anterior teeth were not in contact. The patient’s tongue posture habit likely contributed to this situation. The left maxillary lateral incisor was in palatoversion, possibly due to the unerupted left maxillary canine. Both maxillary first molars were rotated mesially. Mild spacing was observed between the premolars in the mandibular arch. Periodontal and oral mucosal tissues appeared healthy.

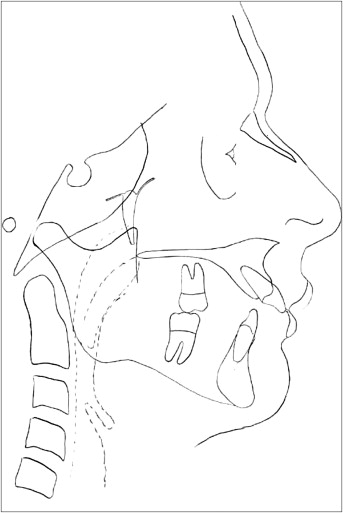

The panoramic radiograph ( Fig 3 ) suggested the presence of a maxillary sinus retention cyst in the area of the maxillary left incisors and canine. An endodontist diagnosed internal resorption of the maxillary left central incisor. The fully developed left maxillary canine was impacted. However, it appeared to push the left lateral incisor root buccally, promoting palatoversion of the lateral incisor crown. Development and eruption of all second molars were incomplete. All third molars were developing and not erupted. The pretreatment cephalometric tracing measurements showed an ANB angle of 5° ( Fig 4 , Table 1 ). A horizontal growth pattern was present, even though the antegonial notch was very pronounced, and the anterior portion of the mandible had a vertical tendency. Maxillary incisors were extremely proclined (U1-FH, 129°), but the mandibular incisors were within normal limits (L1-MP, 91°).

| Analysis | Initial Jul 7, 2003 |

Pretreatment Oct 18, 2004 |

Posttreament Aug 09, 2007 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Skeletal | |||

| Ba-S-Na | 145° | 145° | 144° |

| SNA | 74° | 73° | 71° |

| SNB | 68° | 68° | 67° |

| ANB | 6° | 5° | 4° |

| FH-NPg | 86° | 85° | 84° |

| FH-MPl | 24° | 23° | 26° |

| Y-Axis (FH-SGn) | 58° | 58° | 60° |

| Facial Axis (BaN-CCGn) | 87° | 88° | 86° |

| Wits | 3 mm | 7 mm | 1 mm |

| Dentition | |||

| U1-FH | 125,5° | 129° | 107° |

| U1-NA | 35° | 40° | 22° |

| U1-L1 | 122° | 117° | 126° |

| L1-MPl | 89° | 91° | 101° |

| L1-NB | 18° | 18,5° | 29° |

| Soft tissue | |||

| Upper lip to S-line | 1 mm | 1 mm | −2 mm |

| Upper lip to E-line | −2 mm | −2 mm | −6 mm |

| Lower lip to E-line | −4 mm | −4 mm | −3 mm |

Treatment objectives

The primary treatment objective was to establish a harmonious facial profile and a physiologic occlusion. Initially, the tongue posture habit would be treated using tongue spurs soldered to a mandibular lingual arch. This would be followed by the extraction of the maxillary right first premolar to reduce the overjet and to finish the case in bilateral molar Class II and canine Class I relationships on the right side. Uncovering the maxillary left canine would allow for integration and alignment of that tooth in the dental arch. Since the maxillary left central incisor was severely compromised, no effort would be made to save it. The treatment plan also included moving the maxillary left lateral incisor into the position of the left central incisor and the maxillary left canine into the position of the lateral incisor. Both left lateral incisor and canine would be cosmetically restored to match as closely as possible, the shape, size, and color of the right central and lateral incisors. The maxillary left first premolar would be restored to function as a canine.

The mandibular dentition would be aligned ideally, and the spaces closed. The overjet would be reduced and a normal overbite would be established after eliminating the tongue posture habit. The benefits to the patient of this treatment plan would include a natural occlusion, with no implants or crown or bridge work needed in the area of the left central incisor. The disadvantages of the treatment plan would reveal themselves toward the final treatment stages. In fact, mismatching tooth shape, color, and size are often contributing factors for failing canine-substitution cases. Poorly controlled retention could also lead to an opening of the extraction space.

It was recommended that the oral surgeon assess the suspected maxillary sinus retention cyst at the time of the canine exposure, and if necessary remove it (it is usually not necessary). Extraction of the third molars should be re-evaluated at the final assessment of orthodontic treatment.

Treatment objectives

The primary treatment objective was to establish a harmonious facial profile and a physiologic occlusion. Initially, the tongue posture habit would be treated using tongue spurs soldered to a mandibular lingual arch. This would be followed by the extraction of the maxillary right first premolar to reduce the overjet and to finish the case in bilateral molar Class II and canine Class I relationships on the right side. Uncovering the maxillary left canine would allow for integration and alignment of that tooth in the dental arch. Since the maxillary left central incisor was severely compromised, no effort would be made to save it. The treatment plan also included moving the maxillary left lateral incisor into the position of the left central incisor and the maxillary left canine into the position of the lateral incisor. Both left lateral incisor and canine would be cosmetically restored to match as closely as possible, the shape, size, and color of the right central and lateral incisors. The maxillary left first premolar would be restored to function as a canine.

The mandibular dentition would be aligned ideally, and the spaces closed. The overjet would be reduced and a normal overbite would be established after eliminating the tongue posture habit. The benefits to the patient of this treatment plan would include a natural occlusion, with no implants or crown or bridge work needed in the area of the left central incisor. The disadvantages of the treatment plan would reveal themselves toward the final treatment stages. In fact, mismatching tooth shape, color, and size are often contributing factors for failing canine-substitution cases. Poorly controlled retention could also lead to an opening of the extraction space.

It was recommended that the oral surgeon assess the suspected maxillary sinus retention cyst at the time of the canine exposure, and if necessary remove it (it is usually not necessary). Extraction of the third molars should be re-evaluated at the final assessment of orthodontic treatment.

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses