Introduction

A systematic review of effects related to patient, screw, surgery, and loading on the stability of miniscrews was conducted.

Methods

Reports of clinical trials published before September 2007 with at least 30 miniscrews were reviewed. Parameters examined were patient sex and age, location and method of screw placement, screw length and diameter, time, and amount of loading.

Results

Fourteen clinical trials included 452 patients and 1519 screws. The mean overall success rate was 83.8% ± 7.4%. Patient sex showed no significant differences. In terms of age, 1 of 5 studies with patients over 30 years of age showed a significant difference ( P <0.05). Screw diameters of 1 to 1.1 mm yielded significantly lower success rates than those of 1.5 to 2.3 mm. One study reported significantly lower success rates for 6-mm vs 8-mm long miniscrews (72% vs 90%). Screw placement with or without a surgical flap showed contradictory results between studies. Three studies showed significantly higher success rates for maxillary than for mandibular screws. Loading and healing period were not significant in the miniscrews’ success rates.

Conclusions

All 14 articles described success rates sufficient for orthodontic treatment. Placement protocols varied markedly. Screws under 8 mm in length and 1.2 mm in diameter should be avoided. Immediate or early loading up to 200 cN was adequate and showed no significant influence on screw stability.

In 1997, Kanomi first mentioned a temporarily placed miniscrew for orthodontic anchorage. The following years brought more refined screw designs. Miniscrews have now become established orthodontic anchorage aids, with diameters of 1 to 2.3 mm and lengths of 4 to 21 mm. Nevertheless, many case reports and only a few comprehensive studies have been published on orthodontic miniscrews. The articles promised bright treatment prospects but often lacked evidence-based results. Hence, studies on screw design as well as surgical and orthodontic treatment procedures are much needed. The aims of this review were to analyze the reported success rates of miniscrews and to define guidelines for their selection and application.

Material and methods

A Medline search was conducted with 2 search-term combinations: [screw orthodontic] and [implant orthodontic]. The terms were chosen generally, since there has been little conformity on the nomenclature. A set of criteria was defined to subsequently filter the resulting articles: (1) studies on orthodontic mini-implants or miniscrews published in either English or German, (2) human clinical trials, (3) no case reports or case series, (4) no studies with fewer than 30 miniscrews, and (5) additional data on factors related to the patient, miniscrew, surgery, and loading available for correlation with the miniscrews’ success rates.

References in the criteria-matching results were searched for additional articles.

When available, data were extracted that correlated with the miniscrews’ success rate: patient sex and age, screw length and diameter, method and location of placement, time, and amount of loading.

The statistical analyses of these uniformly formatted data and their graphic representation were made by using SPSS software (version 13 for Mac OS X, SPSS, Chicago, Ill).

Results

As of September 2007, the MedLine search with the terms [screw orthodontic] and [implant orthodontic] returned 734 results. Of those, 14 articles matched all criteria and were considered ( Table I ).

| Authors | Title | Journal | Year |

|---|---|---|---|

| Miyawaki et al | Factors associated with the stability of titanium screws placed in the posterior region for orthodontic anchorage | Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop | 2003 |

| Cheng et al | A prospective study of the risk factors associated with failure of mini-implants used for orthodontic anchorage | Int J Maxillofac Implants | 2004 |

| Liou et al | Do miniscrews remain stationary under orthodontic forces? | Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop | 2004 |

| Fritz et al | Clinical suitability of titanium microscrews for orthodontic anchorage—preliminary experiences | J Orofac Orthop | 2004 |

| Park et al | Group distal movement of teeth using microscrew implant anchorage | Angle Orthod | 2005 |

| Motoyoshi et al | Recommended placement torque when tightening an orthodontic mini-implant | Clin Oral Implants Res | 2006 |

| Park et al | Factors affecting the clinical success of screw implants used as orthodontic anchorage | Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop | 2006 |

| Chen et al | The use of microimplants in orthodontic anchorage | J Oral Maxillofac Surg | 2006 |

| Tseng et al | The application of mini-implants for orthodontic anchorage | Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg | 2006 |

| Herman et al | Mini-implant anchorage for maxillary canine retraction: a pilot study | Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop | 2006 |

| Kuroda et al | Clinical use of miniscrew implants as orthodontic anchorage: success rates and postoperative discomfort | Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop | 2007 |

| Wiechmann et al | Success rate of mini- and micro-implants used for orthodontic anchorage: a prospective clinical study | Clin Oral Implants Res | 2007 |

| Motoyoshi et al | Application of orthodontic mini-implants in adolescents | Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg | 2007 |

| Chen et al | A retrospective analysis of the failure rate of three different orthodontic skeletal anchorage systems | Clin Oral Implants Res | 2007 |

The overall success rates were available in all 14 articles and ranged from 59.4% to 100%. The mean success rate for all 14 studies averaged 83.6% ± 10.2%. Weighted by the number of screws in each study, the mean success rate was 83.8% ± 7.4%. The number of treated patients ranged from 13 to 129, with the number of miniscrews from 30 to 273. Overall, the analyzed data comprised 452 patients treated with 1519 screws ( Table II ).

| Authors | Screws (n) | Patients (n) | Success rate (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Miyawaki et al | 134 | 44 | 77.8 |

| Cheng et al | 92 | 44 ∗ | 91.3 |

| Liou et al | 32 | 16 | 100 |

| Fritz et al | 36 | 17 | 70.0 |

| Park et al (2005) | 30 | 13 | 90.0 |

| Motoyoshi et al (2006) | 124 | 41 | 85.5 |

| Park et al (2006) | 227 | 87 | 91.6 |

| Chen et al (2006) | 59 | 29 | 84.7 |

| Tseng et al | 45 | 25 | 91.1 |

| Herman et al | 49 | 16 | 59.4 |

| Kuroda et al | 116 | 58 | 86.2 |

| Wiechmann et al | 133 | 49 | 76.7 |

| Motoyoshi et al (2007) | 169 | 57 | 85.2 |

| Chen et al (2007) | 273 | 129 ∗ | 81.0 |

| Total | 1519 | 452 | Mean: 83.6 ± 10.2 |

| Mean weighted by number of screws: 83.8 ± 7.4 |

The success rate of the miniscrews was broken down by sex in 6 studies and by age in 4 studies. This did not include the findings of Liou et al, who treated only female patients of 1 age group. No statistically significant findings in terms of patient sex were observed in any studies, but Chen et al found significantly greater success in patients over 30 years of age ( Table III ).

| Authors | Male | Female | <20 years | 20-30 years | >30 years | Mean age |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Miyawaki et al | 80 | 84.7 | 80.3 | 88.2 | 85.0 | 21.8 |

| Cheng et al | – | – | – | – | – | 29.0 |

| Liou et al | – | 100 | – | 100 | – | – |

| Fritz et al | – | – | – | – | – | 29.0 |

| Park et al (2005) | 91.7 | 88.9 | 83.3 | 100 | – | 17.9 |

| Motoyoshi et al (2006) | 90.0 | 85.1 | – | – | – | 24.9 |

| Park et al (2006) | 88.8 | 93.5 | – | – | – | 15.5 |

| Chen et al (2006) | – | – | – | – | – | 29.8 |

| Tseng et al | – | – | – | – | – | 29.9 |

| Herman et al | – | – | – | – | – | 13.7 |

| Kuroda et al | 85.7 | 88.9 | 92.5 | 82.4 | 100 | 21.8 |

| Wiechmann et al | – | – | – | – | – | 26.9 |

| Motoyoshi et al (2007) | – | – | 78.3 | 91.9 | – | – |

| Chen et al (2007) | 84.4 | 85.4 | 78.3 ∗ | 84.1 ∗ | 93.6 ∗ | 24.5 |

The data for screw length and diameter were given in all included studies. Length ranged from 4 to 21 mm and diameter from 1 to 2.3 mm. Nine studies reported success rates for screws of either different lengths or different diameters. Three of them reported statistically significant findings ( P <0.05). Miyawaki et al concluded that their 1-mm thick screw performed significantly worse than those with diameters of 1.5 and 2.3 mm. Similarly, Wiechmann et al reported worse results for 1.1-mm thick screws than for 1.6-mm ones. In the study of Chen et al, the success rate of 6-mm long screws was significantly lower than that of 8-mm long ones ( P <0.05) ( Table IV ).

| Authors | Screws (n) | Length | Diameter | Success rate |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Miyawaki et al | 10 | 6 | 1 | 0.0 ∗ |

| 101 | 11 | 1.5 | 83.9 ∗ | |

| 23 | 14 | 2.3 | 85 ∗ | |

| Cheng et al | 48 | 5, 7 | 2 | 85.4 |

| 31 | 9 | 2 | 93.5 | |

| 31 | 11 | 2 | 93.0 | |

| 20 | 13 | 2 | 85.0 | |

| 10 | 15 | 2 | 90.0 | |

| Liou et al | 32 | 17 | 2 | 100 |

| Fritz et al | 36 | 6, 8, 10 | 1.4, 1.6, 2 | 70.0 |

| Park et al (2005) | 4 | 4 | 1.2 | 75.0 |

| 14 | 6 | 1.2 | 86.7 | |

| 8 | 8 | 1.2 | 100 | |

| 2 | 10 | 1.2 | 100 | |

| 2 | 15 | 2 | 100 | |

| Motoyoshi et al (2006) | 124 | 8 | 1.6 | 85.5 |

| Park et al (2006) | 19 | 5 | 1.2 | 84.2 |

| 157 | 6-8 | 1.2 | 93.6 | |

| 46 | 4-10 | 1.2 | 89.1 | |

| 5 | 10-15 | 2 | 80.0 | |

| Chen et al (2006) | 18 | 6 | 1.2 | 72.2 ∗ |

| 41 | 8 | 1.2 | 90.2 ∗ | |

| Tseng et al | 15 | 8 | 2 | 80.0 |

| 10 | 10 | 2 | 90.0 | |

| 12 | 12 | 2 | 100 | |

| 8 | 14 | 2 | 100 | |

| Herman et al | 49 | 6-10 | 1.8 | 61.2 |

| Kuroda et al | 37 | 7, 11 | 2, 2.3 | 81.1 |

| 13 | 6 | 1.3 | 69.2 | |

| 6 | 7 | 1.3 | 83.3 | |

| 45 | 8 | 1.3 | 93.3 | |

| 12 | 10 | 1.3 | 91.7 | |

| 3 | 12 | 1.3 | 100 | |

| Wiechmann et al | 79 | 5-10 | 1.1 | 59.6 ∗ |

| 54 | 5-10 | 1.6 | 87.0 ∗ | |

| Motoyoshi et al (2007) | 169 | 8 | 1.6 | 91.9 |

| Chen et al (2007) | 72 | 4-10 | 1.2 | 76.4 |

| 201 | 5-21 | 2 | 82.6 |

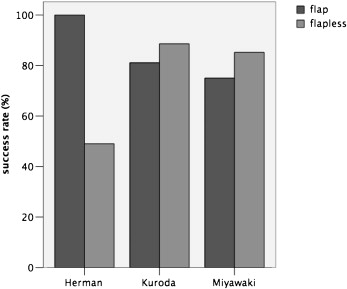

The method and the location of screw placement were described in all studies. All authors but Miyawaki et al used pilot drilling before placing the screw. Both flap and flapless surgery were performed. Four studies used a mucoperiosteal flap, and 7 studies used a flapless method. In the remaining 3 studies, both flap and flapless surgery were performed, and the corresponding success rates were examined. Although Miyawaki et al and Kuroda et al reported slightly higher success rates for flapless placement, the results of Herman et al were considerably better with a flap ( Fig ).

When information was available, 958 screws were used in the maxilla with a mean success rate 89.0% ± 10.0%. In the mandible, 508 screws averaged a success rate of 79.6% ± 8.7%. Weighted by the number of screws in each location, the mean success rates were 87.9% ± 7.6% for the maxilla and 80.4% ± 8.5% for the mandible. In 3 studies, the differences between the maxilla and the mandible were significant ( P <0.05) in favor of the maxilla ( Table V ).

| Maxilla | Mandible | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Authors | Screws (n) | Success rate | Screws (n) | Success rate |

| Miyawaki et al | 63 | 84.1 | 61 | 83.6 |

| Cheng et al | – | 93.3 ∗ | – | 77.1 ∗ |

| Liou et al | 32 | 100 | – | – |

| Fritz et al | 18 | – | 18 | – |

| Park et al (2005) | 8 | 100 | 22 | 86.4 |

| Motoyoshi et al (2006) | 80 | 88.8 | 44 | 79.5 |

| Park et al (2006) | 124 | 96.0 ∗ | 103 | 86.4 ∗ |

| Chen et al (2006) | 43 | 86.0 | 16 | 81.3 |

| Tseng et al | 27 | 96.3 | 18 | 83.3 |

| Herman et al | 49 | 61.2 | – | – |

| Kuroda et al | 61 | 91.8 | 18 | 77.8 |

| Wiechmann et al | 90 | 86.7 | 43 | 55.8 |

| Motoyoshi et al (2007) | 100 | 84.0 | 69 | 87.0 |

| Chen et al (2007) | 263 | 88.2 ∗ | 96 | 77.1 ∗ |

| Total | 958 | Mean: 89.0 ± 10.0 | 508 | Mean: 79.6 ± 8.7 |

| Weighted by number of screws | Mean weighted by number of screws: 87.9 ± 7.6 | Mean weighted by number of screws: 80.4 ± 8.5 | ||

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses