The most common site of all mandibular fractures is the condylar or subcondylar region, where 9% to 45% of mandibular fractures occur. The volume of debate about diagnosis and management of injuries to the temporomandibular joint (TMJ) sheds light on the difficulty associated with managing and repairing these complex injuries.

Etiopathogenesis/Causative Factors

The etiology of subcondylar fractures mirrors that of most facial trauma. In adults, the most common causes of subcondylar fractures of the mandible are motor vehicle accidents, interpersonal violence, work-related incidents, sporting accidents, and falls. In children, the most common causes are falls and bicycle accidents, although motor vehicle accidents also play an important role.

Pathologic Anatomy

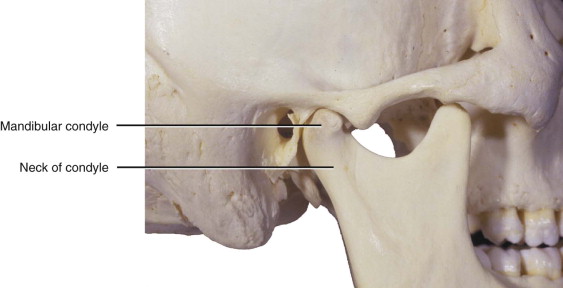

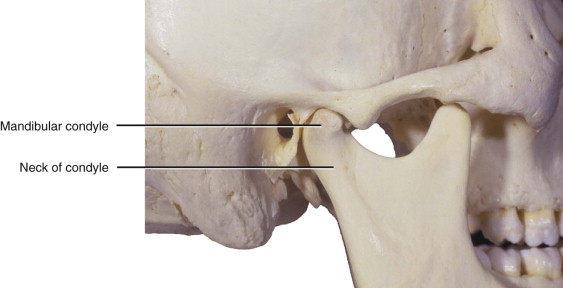

Subcondylar fractures of the mandible are defined as fractures below the level of the most inferior point on the sigmoid notch ( Fig. 38-1 ). Depending on the circumstances, condylar neck fractures may be treated as subcondylar fractures; displacement and malocclusion in the setting of a long condylar neck (the ability to place at least two screws in the segment) would qualify. Historically, two systems have been developed for the classification of subcondylar fractures: the Lindahl system and the MacLennan system ( Boxes 38-1 and 38-2 ). The main objectives of these classifications systems are to describe the relationship of the condyle to the glenoid fossa and the relationship between the fractured proximal and distal segments. The condylar head can remain in the fossa, can be dislocated out of the fossa either medially or laterally, or in rare cases can be dislocated into a fractured fossa. Fractured subcondylar segments can be nondisplaced (hairline fracture); alternatively, the proximal segment may be displaced either medially or laterally relative to the distal segment. Most of these fractures will be described as closed fractures unless they are associated with deep facial lacerations.

The Lindahl system classifies subcondylar fractures according to their anatomic location and the specific relationship between the fractured condyle and the glenoid fossa. The anatomic location of the fracture is described first. The most superior fracture is in the condylar head, which means that the fracture probably lies in the capsule of the temporomandibular joint; the second is a fracture in the thin neck of the condyle. The most inferior fracture lies in the subcondylar region below the anatomic neck and extends to the inferior portion of the ramus.

Relationship of the condylar segment to the mandibular fragment :

- 1

Nondisplaced.

- 2

Deviated: angulation of the condylar head without dislocation of the fractured segments.

- 3

Displaced with medial or lateral overlap. The fractured condylar head lies either medial or lateral to the distal segment, with overlap. A medial position is more common because of the attachment and traction of the lateral pterygoid.

Relationship between the condylar head and the glenoid fossa :

- 1

Nondisplaced.

- 2

Displaced: the condylar head remains in the fossa, but the joint space is altered.

- 3

Dislocation. The condylar head lies completely outside the anatomic fossa. This position requires rupture of the capsule.

-

Type I fracture, nondisplaced.

-

Type II fracture, deviated. Angulation without overlap or separation. Greenstick fractures are included in this category.

-

Type III fracture, displaced. This fracture displays overlap between the proximal and distal segments.

-

Type IV fracture, dislocated. The condylar head leaves the capsule and lies outside the glenoid fossa. The location could be medial, lateral, anterior, or posterior.

Pathologic Anatomy

Subcondylar fractures of the mandible are defined as fractures below the level of the most inferior point on the sigmoid notch ( Fig. 38-1 ). Depending on the circumstances, condylar neck fractures may be treated as subcondylar fractures; displacement and malocclusion in the setting of a long condylar neck (the ability to place at least two screws in the segment) would qualify. Historically, two systems have been developed for the classification of subcondylar fractures: the Lindahl system and the MacLennan system ( Boxes 38-1 and 38-2 ). The main objectives of these classifications systems are to describe the relationship of the condyle to the glenoid fossa and the relationship between the fractured proximal and distal segments. The condylar head can remain in the fossa, can be dislocated out of the fossa either medially or laterally, or in rare cases can be dislocated into a fractured fossa. Fractured subcondylar segments can be nondisplaced (hairline fracture); alternatively, the proximal segment may be displaced either medially or laterally relative to the distal segment. Most of these fractures will be described as closed fractures unless they are associated with deep facial lacerations.

The Lindahl system classifies subcondylar fractures according to their anatomic location and the specific relationship between the fractured condyle and the glenoid fossa. The anatomic location of the fracture is described first. The most superior fracture is in the condylar head, which means that the fracture probably lies in the capsule of the temporomandibular joint; the second is a fracture in the thin neck of the condyle. The most inferior fracture lies in the subcondylar region below the anatomic neck and extends to the inferior portion of the ramus.

Relationship of the condylar segment to the mandibular fragment :

- 1

Nondisplaced.

- 2

Deviated: angulation of the condylar head without dislocation of the fractured segments.

- 3

Displaced with medial or lateral overlap. The fractured condylar head lies either medial or lateral to the distal segment, with overlap. A medial position is more common because of the attachment and traction of the lateral pterygoid.

Relationship between the condylar head and the glenoid fossa :

- 1

Nondisplaced.

- 2

Displaced: the condylar head remains in the fossa, but the joint space is altered.

- 3

Dislocation. The condylar head lies completely outside the anatomic fossa. This position requires rupture of the capsule.

-

Type I fracture, nondisplaced.

-

Type II fracture, deviated. Angulation without overlap or separation. Greenstick fractures are included in this category.

-

Type III fracture, displaced. This fracture displays overlap between the proximal and distal segments.

-

Type IV fracture, dislocated. The condylar head leaves the capsule and lies outside the glenoid fossa. The location could be medial, lateral, anterior, or posterior.

Diagnostic Studies

Panoramic radiographs and Towne projection radiographs are effective methods of evaluating the subcondylar region of the mandible. However, computed tomography (CT) is currently the state of the art for detecting subcondylar fractures of the mandible. Three-dimensional reconstructions of CT data offer the surgeon invaluable information about the position of the fractured segments, thereby allowing the most accurate planning of fracture management.

Treatment/Reconstructive Goals

The goals of treating any type of trauma are to restore pain-free, premorbid form and function. With respect to subcondylar fractures of the mandible, the goal is restoration or maintenance of facial symmetry and posterior mandibular height. Treatment should be completed without injury to the parotid gland or the facial nerve and, preferably, without obvious scarring. Ideal restoration of function after treatment of a subcondylar fracture includes re-establishment of maximum mandibular movements: a maximum incisal opening (MIO) of 40 mm without deviation, lateral excursive movements of greater than 5 mm to the right and left, and the absence of signs or symptoms of temporomandibular disorder.

Specific Treatment and Techniques

Surgical Anatomy to Consider

The facial nerve exits the skull from the stylomastoid foramen and passes obliquely inferiorly and laterally until it enters the parotid gland. The common facial divisions of the nerve are the temporal, zygomatic, buccal, marginal mandibular, and cervical divisions. The branches most at risk during a transfacial approach to the subcondylar region are the buccal and marginal mandibular branches; those most at risk during an approach to the TMJ or an intracapsular fracture are the zygomatic and temporal branches.

The confluence of the superficial temporal vein and the maxillary vein is called the retromandibular vein. This vascular structure can be the source of substantial bleeding deep to the ramus and the neck of the condyle because it descends just posterior to the ramus of the mandible through the parotid gland. This vein is lateral to the external carotid artery.

Closed Management

Closed management is performed more than any other type of management because of its ease and long history of use. It is indicated for very specific subcondylar fractures, two of which are greenstick fractures in pediatric patients and nondisplaced fractures that do not “fall back” under anesthesia in adults. In addition, closed management is indicated for the treatment of any patient who refuses surgery as an option. The technique can be applied variably: as a liquid diet (as in the situation with greenstick fractures in pediatric patients), as maxillomandibular fixation (MMF) with arch bars and wires, or as fixation with arch bars and elastic bands. Likewise, elastic bands may be used either in a light, guiding fashion or in a heavy fashion, in which case they are very similar to wire fixation.

Although closed management may still be commonplace, it cannot be considered the state of the art. It has even been shown that treatment by MMF may be associated with a higher incidence of temporomandibular dysfunction postoperatively than seen with other types of treatment and that closed treatment may not prevent further displacement of the fractured subcondylar segments. However, closed management can avoid the risks associated with general anesthesia, facial nerve injury, parotid injury, and scarring and can also shorten the duration of soft tissue swelling after the injury.

Open Reduction with Internal Fixation

Indications

Zide and Kent presented the absolute and relative indications for open reduction of mandibular condylar fractures ( Box 38-3 ). Since their presentation of the clinical standard, many improvements have been made in rigid internal fixation and endoscopic application to craniofacial fractures, and these improvements have allowed expanded indications for open reduction and internal fixation (ORIF) of subcondylar fractures. More recent studies have focused on the complications associated with open and closed treatment of subcondylar fractures of the mandible ( Box 38-4 ).

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses