Fractures of the mandible are common. While diagnosis is usually straightforward, there are some occasions when signs and symptoms are subtle, particularly if there are associated injuries. Restoration of the occlusion is central to good outcomes. Both the presence and absence of teeth can complicate treatment. Early return to function is important to avoid complications of the temporomandibular joint apparatus and maximize patient satisfaction. This chapter will review the etiology, diagnosis, and management of fractures of the mandible, excluding fractures of the mandibular condyle, which will be covered elsewhere.

Etiopathogenesis

Fractures of the mandible can occur as the result of high-energy or low-energy trauma. In the presence of marked atrophy of the mandible, secondary to tooth loss or intrabony pathology (e.g., cysts, tumor), the causative trauma may not be noticed by the patient. In the case of high-energy trauma, the potential for other injuries must be remembered, particularly the cervical spine, upper airway, maxilla, and brain. Assessment and management of patients with mandibular injuries should always take place within the context of the Advanced Trauma Life Support (ATLS) principles established by the American College of Surgeons and accepted around the world.

Pathologic Anatomy

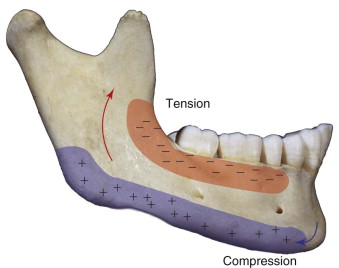

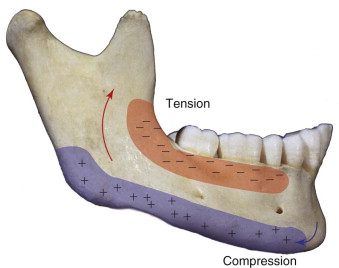

The mandible is a U -shaped bone that articulates bilaterally with the temporal bones through the temporomandibular joints (TMJs). During function of the intact mandible, both TMJs have to move. When the mandible is fractured, the muscles acting on the mandible are able to displace the fragments in a horizontal and vertical plane. The forces generated give rise to areas of tension and compression as described by Champy ( Figs. 37-1 and 37-2 ). An appreciation of the areas of tension and compression can be utilized to provide functionally stable fixation. The inferior alveolar nerve runs through the mandible from the lingula to the mental foramen and is at risk of damage both as the result of the injury and during fixation of the fracture. The position of the nerve changes with growth of the mandible and loss of alveolar bone secondary to tooth loss. Any altered sensation of the inferior alveolar nerve distribution must be noted at the time of the initial examination. The occlusion of the mandibular teeth with the maxillary teeth can be used as a guide to reduction of fractures. The teeth can also be used as a source of fixation (maxillomandibular fixation [MMF]). In the pediatric mandible, the presence of unerupted teeth can limit the placement of rigid fixation, and unerupted teeth can act as areas of weakness predisposed to fracture. This is particularly seen with unerupted third molars (wisdom teeth). With tooth loss, atrophy of the alveolar process can occur. If extreme, this can dramatically reduce the bony volume of the mandible, making it susceptible to fracture from minimal trauma and making it difficult to apply fixation. The position of the branches of the facial nerve must be appreciated if a transcutaneous approach to repair is being considered.

Pathologic Anatomy

The mandible is a U -shaped bone that articulates bilaterally with the temporal bones through the temporomandibular joints (TMJs). During function of the intact mandible, both TMJs have to move. When the mandible is fractured, the muscles acting on the mandible are able to displace the fragments in a horizontal and vertical plane. The forces generated give rise to areas of tension and compression as described by Champy ( Figs. 37-1 and 37-2 ). An appreciation of the areas of tension and compression can be utilized to provide functionally stable fixation. The inferior alveolar nerve runs through the mandible from the lingula to the mental foramen and is at risk of damage both as the result of the injury and during fixation of the fracture. The position of the nerve changes with growth of the mandible and loss of alveolar bone secondary to tooth loss. Any altered sensation of the inferior alveolar nerve distribution must be noted at the time of the initial examination. The occlusion of the mandibular teeth with the maxillary teeth can be used as a guide to reduction of fractures. The teeth can also be used as a source of fixation (maxillomandibular fixation [MMF]). In the pediatric mandible, the presence of unerupted teeth can limit the placement of rigid fixation, and unerupted teeth can act as areas of weakness predisposed to fracture. This is particularly seen with unerupted third molars (wisdom teeth). With tooth loss, atrophy of the alveolar process can occur. If extreme, this can dramatically reduce the bony volume of the mandible, making it susceptible to fracture from minimal trauma and making it difficult to apply fixation. The position of the branches of the facial nerve must be appreciated if a transcutaneous approach to repair is being considered.

Diagnostic Studies

A good clinical examination remains the mainstay of diagnosis of mandibular fractures. The patient should be evaluated for the presence of derangement of the occlusion, altered sensation of the inferior alveolar nerve distribution, and step-offs in the dentition.

While improved access to computed tomography (CT) scanning has increasingly led to this technique being adopted as the gold standard for assessment, most fractures can be diagnosed on panoramic (Panorex, Orthopantomogram) radiographs. Posteroanterior (PA) radiographs and reverse Towne radiographs can help to diagnose condylar injuries. Where CT facilities are unavailable, lower occlusal radiographs can show subtle fractures involving the lingual plate in the symphyseal region. Periapical films may be required for dentoalveolar fractures. The mechanisms of injury leading to mandibular fractures can also cause injuries to the cervical spine, and imaging of the cervical spine should be considered, particularly in patients with a history of altered consciousness or distracting injuries.

If available, previous dental models can be helpful in establishing the preinjury occlusion if there are multiple and/or comminuted fractures.

Treatment/Reconstructive Goals

The goals of treatment of fractures of the mandible are:

- 1

Restoration of the preinjury occlusion

- 2

Early return of function

- 3

Acceptable cosmesis

In the dentate patient, restoration of the premorbid occlusion is crucial. Questioning of the patient about his preinjury occlusion is crucial, and dental models, if available in cases where the occlusion is not obvious, can be valuable in helping to determine the occlusion.

Reduction of the fractures may be open or closed. In closed reduction, the occlusion is used as an indirect guide to the adequacy of the reduction. Fixation of the fractures is usually required, although some undisplaced fractures may be managed conservatively, particularly in children. Fixation may be external or internal ( Box 37-1 ).

| External Fixation | Internal Fixation |

|---|---|

|

|

MMF , maxillomandibular fixation.

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses