Unilateral condylar hyperplasia (CH) is an uncommon pathologic entity with a wide spectrum of clinical manifestations that results from the overgrowth of one condyle. Lack of consistent terminology has contributed to the confusion with this diagnosis, but the common underlying feature is hypertrophy or hyperplasia of the mandibular condyle. Depending on the age at onset, and rapidity, and duration of the condylar growth, facial asymmetry and, associated malocclusions are common. CH is usually self-limited, and after cessation of growth, orthognathic surgery may be needed to correct the resultant asymmetry. Condylectomy is indicated if growth is rapid and causes functional or psychosocial problems. The purpose of this chapter is to review the etiopathogenesis, pathologic anatomy, diagnostic studies, and treatment options for correction of unilateral CH and its associated manifestations.

Etiopathogenesis

CH is a rare disorder characterized by excessive unilateral growth of the mandibular condyle. Although the precise etiology is uncertain, it is generally agreed that one of two processes occur: either excess growth of one condyle or continued unilateral condylar growth after completion of skeletal growth. Trauma, infection, hormonal disturbances, and a genetic predisposition have been implicated in the pathogenesis of CH. Common to all cases of CH, the pathology occurs within the temporomandibular joint (TMJ). Manifestations of CH are not limited to the mandible and may involve the maxilla and even the orbits. Malocclusion is common, and TMJ pain and dysfunction may also be seen. CH has been described in all ethnicities and both sexes with a slight female predilection.

Although the onset of CH can vary widely, it generally begins in early adolescence and ceases in the second and third decades; though condylar growth has been found to continue into the 50s and 60s. Histologic analysis of affected condyles has shown increased width of the overlying fibrocartilaginous layer with undifferentiated germinating mesenchymal cells, islands of chondrocytes in the subchondral bone, and large masses of hyaline cartilage. Once the hyperplastic growth has ceased, the histologic appearance of the condyle is normal.

The spectrum of facial asymmetry associated with CH depends on three factors: (1) age at onset, (2) duration, and (3) degree of abnormal growth. Obwegeser and Makek categorized CH into three groups based on the primary direction of mandibular growth (vertical or horizontal). They described hemimandibular hyperplasia as asymmetric enlargement of the condylar head and neck, mandibular ramus, and body up to the symphysis with elongation and bowing of the inferior border of the mandible. In cases of early onset, compensatory vertical maxillary growth can result in canting of the occlusal plane. In contrast, if condylar growth was rapid, an open bite on the affected side could also be seen. The second group, described as hemimandibular elongation, was characterized by lateral deviation of the mandible and chin without vertical lengthening of the ramus. The third category was a combination of the two. With the advent of three-dimensional imaging, it appears likely that CH represents a continuum with varying degrees of both vertical and horizontal growth components.

Pathologic Anatomy

The pathologic anatomy of CH is ascertained from the clinical examination, supporting imaging studies, and history of the asymmetry ( Table 81-1 ). Progression of the asymmetry is often slow and may not be clinically apparent to the patient until clinical signs of TMJ dysfunction or malocclusion are noted.

| DIAGNOSIS | ONSET | CLINICAL FINDINGS | IMAGING FINDINGS |

|---|---|---|---|

| Condylar hyperplasia | 13-30 years |

|

|

| Condylar tumors: osteochondroma, osteoma, chondroma, osteoblastoma | 40.5 years |

|

|

| Torticollis | Congenital |

|

|

| Condylar hypoplasia/degeneration | 1st-6th decades |

|

|

| Condylar fracture | Any |

|

|

| Craniofacial syndromes: hemifacial microsomia, hypomelanosis of Ito | Congenital |

|

|

Clinical Examination

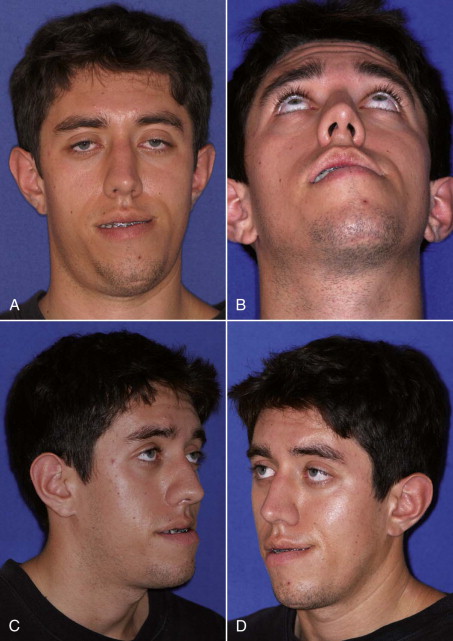

The most salient information is obtained from clinical evaluation with the patient in repose and animation. Anatomic components are assessed from the frontal, oblique, and profile views, with additional views obtained as needed. Evaluation of the patient from the basal (worm’s eye) and cranial (bird’s eye) views can provide additional information about the location, magnitude, and three-dimensional characterization of the asymmetry. Examination of the patient during dynamic function, while speaking and smiling, provides additional information about the soft tissue response to the asymmetry.

Clinical examination begins with the upper third of the face. Varying degrees of orbital dystopia may be seen in patients with CH, depending on the magnitude of the asymmetric growth and the age at which the growth began. Patients with hemimandibular hyperplasia can have associated orbital dystopia because of distortion of the middle and anterior cranial fossae ( Fig. 81-1 ). The level of the orbits is important to consider in planning treatment because the interorbital line, a line drawn tangent to the supraorbital rims, is commonly used as the horizontal reference for measuring maxillary occlusal cant.

Examination of the mid-face and maxilla, in repose and smiling, will further reveal associated maxillary asymmetries, which occur in up to 50% of patients with CH. The maxillary dental midline should be noted. Malar and maxillary asymmetry (projection and yaw) are best assessed from the basal view. Determination of the cant of the labial commissures and occlusal plane is aided by having the patient bite on a tongue blade ( Fig. 81-2 ). This provides a useful horizontal reference plane and can help determine the degree and location of the asymmetry. Smile analysis provides important information about the location and appearance of the asymmetry during dynamic function. A posed smile is voluntary and reproducible. Asymmetric function of the lips during smiling should be differentiated from skeletal asymmetry. Characteristics of an attractive smile, more so for females than males, include absence of visible buccal corridors, adequate exposure of the maxillary teeth, and gingival display above the incisors and premolars. There should be approximately 2 to 3 mm of gingival exposure above the premolars. The amount of gingival display in patients with accompanying maxillary asymmetries is important in determining whether the deficient side should be down-grafted or the elongated side should be impacted ( Fig. 81-3 ).

Condylar hyperplasia is most evident in the lower third of the face, where abnormal chin shape and position are obvious ( Fig. 81-4, A and B ). Bowing of the inferior border of the mandible and deficient width and projection of the mandibular angle are features commonly seen in these cases. Right and left oblique views will further disclose the difference between the mandibular angles ( Fig. 81-4, C and D ). Patients should be queried about which side they believe is more attractive.

A class III malocclusion is frequently associated with CH and midline deviation away from the affected side. A posterior open bite may be present (also on the affected side), and dental compensations consisting of lingual tipping of the mandibular premolars and molars on the contralateral side are common.

TMJ range of motion in patients with CH is largely normal, but approximately 25% complain of pain and dysfunction. Pain and dysfunction are commonly seen in the contralateral TMJ, probably because of compression from growth of the affected joint.

Pathologic Anatomy

The pathologic anatomy of CH is ascertained from the clinical examination, supporting imaging studies, and history of the asymmetry ( Table 81-1 ). Progression of the asymmetry is often slow and may not be clinically apparent to the patient until clinical signs of TMJ dysfunction or malocclusion are noted.

| DIAGNOSIS | ONSET | CLINICAL FINDINGS | IMAGING FINDINGS |

|---|---|---|---|

| Condylar hyperplasia | 13-30 years |

|

|

| Condylar tumors: osteochondroma, osteoma, chondroma, osteoblastoma | 40.5 years |

|

|

| Torticollis | Congenital |

|

|

| Condylar hypoplasia/degeneration | 1st-6th decades |

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses