This article discusses the management of the facial gingival margin before and after tooth removal. Important factors including diagnostic assessment, wound healing, bone resorption and remodeling, gingival thickness, and gingival margin are reviewed, and key procedures suggested. Gingival thickness can have a major influence on the maintenance of the facial gingival margin over the longer term.

Diagnostic assessment

Clinical observations are used to evaluate a patient’s facial appearance. For the esthetic implant restoration, 4 critical areas to document in the initial evaluation include: (1) the smile line and incisor show at rest; (2) the length of the incisor that sets the ideal location of the facial gingival margin; (3) the bone morphology under the gingiva; and (4) the thickness of the patient’s gingiva.

The smile line sets the vertical location of the incisor edge of the maxillary central incisors. Typically the exposure of the central incisor at rest with the lips relaxed and apart is 2 to 4 mm, depending on the patient’s age and gender. As the patient ages he or she tends to show less maxillary tooth at rest. The clinician notes the location of the incisor edge and then may need to fabricate a setup with the ideal location of the incisor edge. This is one of the critical factors when determining the ultimate position of the facial gingival margin.

The length of the central incisor sets the ideal location of the gingival margin. The central incisor is typically 10.5 to 11.0 mm in length. Once the planned, ideal incisor edge position is known, then the ideal location of the facial gingival margin can be established by using the standard 11-mm tall central incisor to apically identify the ideal position of the facial gingival margin.

Diagnostic assessment must also include the quantity and shape of the bone at the crest of the planned implant site. The horizontal projection of the crestal bone and its height will set the stage for the location of the facial gingival margin of the planned implant restoration. If the bone is not sufficient then the facial gingival margin may be apical to ideal, and also may not project forward to simulate root form eminence of a natural tooth in the esthetic zone.

The thickness of the gingiva will be predictive concerning the long-term vertical movement or lack of movement of the facial gingival margin. In the patient with thin gingiva, underlying bone remodeling and apical resorption of the crestal bone will lead to gingival recession. The patient with thick gingiva will have less apical movement over time as bone remodels. It may be important to convert the thin gingiva over an implant site to thick gingiva to slow the process of gingival recession as bone continues to remodel over time.

The critical points mentioned can be combined with 4 additional basic observations of wound healing. These 4 wound healing keys will affect the clinical choices made by the surgeon and restorative dentist as concerns which adjunctive therapies are used when restoring a missing tooth in the esthetic zone of the maxilla.

Keys to remember:

- 1.

Thin bone resorbs over time. The labial bone over an anterior maxillary tooth is usually less than 1.5 mm thick, and may be less than 1.0 mm thick. There is evidence that the natural progression of labial bone thickness is for it to decrease up to 1.0 mm after the implant is placed. If thin bone resorbs then the implant’s surface may become exposed to the soft tissues, with subsequent recession and loss of esthetic appearance.

- 2.

Thin gingiva recedes over time. If the final crown is placed on an anterior maxillary implant with facial gingival margin perfectly located, then subsequent gingival recession will adversely affect the appearance of the patient. In the patient with thick gingiva bone, remodeling apically will result in pocket formation with minimal recession. However, in the patient with thin gingiva bone, remodeling in the apical direction will result in gingival recession and lengthening of the tooth with a poor esthetic result.

- 3.

Allograft particles are resorbed as bone formation occurs, with decrease of the graft volume. Bone resorption of grafts can result in flattening of the crest and an unnatural appearance with loss of the natural root eminence. This point is important to consider when immediately placing an implant into an extraction site, with a gap between the labial surface of the implant and a thin labial cortical plate of bone. If allograft is used and the labial bone resorbs, which is expected, combined with allograft volume thinning, then the ultimate appearance of the site is flat. The use of a relatively nonresorbable material may prevent the development of a flat ridge.

- 4.

The remodeling of bone through healing of a bone defect follows a defined course, which can be minimally affected by grafting. When the clinician recognizes this process then different approaches to the site can be utilized to “mask” bone remodeling and thinning.

Evidence to support the aforementioned keys

Bone remodeling occurs in the crestal region after tooth removal. Block and Kent demonstrated in a dog model that bone will remodel and thin in the crestal area when no graft material is placed in a fresh extraction socket. When particulate hydroxyapatite was placed into the fresh extraction sites, ridge form was maintained. However, histologic evidence showed that the bone remodeled in a very similar pattern, mimicking the normal extraction site healing. Bone was not preserved by the grafting process, only the presence of the nonresorbable material maintained ridge form. This result supports the use of a sintered bovine material, which is relatively nonresorbable as a graft, between the labial surface of an implant and intact thin labial bone, anticipating bone resorption but maintaining the appearance of root form eminence by the presence of the sintered xenograft.

Bone remodeling is a natural process after surgical procedures as well as after tooth removal and implant placement. Cardaropoli and colleagues showed that from the time of abutment connection, a mean loss of bone height at the facial and lingual aspect of the implant amounted to 0.7 to 1.3 mm ( P <.05), whereas no significant change was noted at proximal sites. A mean reduction of 0.4 mm of the labial bone thickness was observed between implant placement and the second-stage surgery.

Evidence to support the aforementioned keys

Bone remodeling occurs in the crestal region after tooth removal. Block and Kent demonstrated in a dog model that bone will remodel and thin in the crestal area when no graft material is placed in a fresh extraction socket. When particulate hydroxyapatite was placed into the fresh extraction sites, ridge form was maintained. However, histologic evidence showed that the bone remodeled in a very similar pattern, mimicking the normal extraction site healing. Bone was not preserved by the grafting process, only the presence of the nonresorbable material maintained ridge form. This result supports the use of a sintered bovine material, which is relatively nonresorbable as a graft, between the labial surface of an implant and intact thin labial bone, anticipating bone resorption but maintaining the appearance of root form eminence by the presence of the sintered xenograft.

Bone remodeling is a natural process after surgical procedures as well as after tooth removal and implant placement. Cardaropoli and colleagues showed that from the time of abutment connection, a mean loss of bone height at the facial and lingual aspect of the implant amounted to 0.7 to 1.3 mm ( P <.05), whereas no significant change was noted at proximal sites. A mean reduction of 0.4 mm of the labial bone thickness was observed between implant placement and the second-stage surgery.

Can we predict bone resorption or the lack thereof?

There is no evidence on how to predict bone resorption of the labial bone after tooth removal. When there is less than 1.0 mm thickness of labial bone then the clinician should expect some of its loss. In such situations, grafting a relatively nonresorbable material may be indicated. If there is extremely thick bone, for example, greater than 1.5 mm thickness, the clinician may believe that this bone will not resorb; however, there is minimal evidence in the literature to support this claim. The author always expects bone to resorb to some degree, and tries to perform adjunctive procedures to anticipate its resorption and a resultant flatter ridge form.

Do Existing Bone Defects on the Labial Surface Affect Gingival Position?

Kan and colleagues looked at this question in a small sample of patients, and concluded that as the size and shape of the labial bone defect increased, there was a greater incidence of gingival recession above 1.5 mm. 8.3% of V-shaped defects, 42.8% of U-shaped defects, and 100% of large-shaped defects had greater than 1.5 mm of gingival recession.

When a tooth is removed and a facial defect exists, the clinician may graft the defect. However, the material chosen must perform several tasks, the first of which is to promote bone formation within the extraction defect to later support an implant. The second is to achieve minimal resorption to promote preservation or recreation of the normal convex ridge profile. Allograft is often chosen because of its reported success with bone formation within 4 months of placement. However, at 4 months and over time, further bone remodeling will often occur with a resultant flattened ridge. In the critical esthetic defect, additional onlay application of a relatively nonresorbable material such as anorganic bovine bone may be necessary to recreate the desired ridge form. Another solution when smaller ridge form corrections are needed is the conversion of thin gingiva to thick gingiva with the placement of a connective tissue graft.

What is the Effect of Gingival Thickness on Maintenance of the Facial Gingival Margin Over Time?

It was noticed as early as 1969, and confirmed, that patients with thin gingiva have gingival recession after osseous surgery around teeth. Patients with thicker gingiva had pocket formation without gingival recession after osseous surgery, simultaneous with crestal bone resorption.

Kan and colleagues reported a series of patients who had subepithelial connective tissue grafts placed under their gingiva on the labial surface of implant sites to change the patients’ thin gingiva to thick gingiva. This conversion resulted in less gingival recession over time. Although this was a relatively small series of patients, this observation has been confirmed by the author. Kan states: “facial gingival recession of thin periodontal biotype seems to be more pronounced than that of thick biotype. Biotype conversion around both natural teeth and implants with subepithelial connective tissue graft has been advocated, and the resulting tissues appear to be more resistant to recession.” Based on these observations, if a tooth in the esthetic region has thin gingiva at the crest, a connective tissue graft should be placed under the gingiva to convert it form thin to thick, resulting in thickened tissue with a better appearance. It also provides the restorative dentist with sufficient tissue to mold and sculpt with prosthetic manipulation.

Implant design may contribute to the ability of clinicians to maintain the position of the facial gingival margin. It is well accepted that a flat, butt joint between the abutment and implant will result in a 1.0-mm dimension inflammatory zone. This zone will adversely affect bone and its movement away from the inflamed area of tissue, resulting in 2 to 3 mm of bone loss from the implant/abutment interface. To circumvent this phenomenon, manufacturers have medialized the interface utilizing internal connections of the abutment to implant, resulting in an average of 0.5 mm crestal bone loss. Of importance, this lack of bone movement in the apical direction results in preservation of the bone around the implant. Bone preservation is circumferential with maintenance of the facial crestal bone, with subsequent less gingival recession because the crestal bone is maintained over time.

Papilla are directly influenced by the underlying bone. If the bone on the adjacent tooth is within 5 to 6 mm of the contact area of the teeth, papilla will usually be normal in appearance. If the crestal bone on the adjacent tooth has undergone resorption then the papilla may be blunted with significant defects noted. The facial gingival margin is not directly influenced by the interdental bone unless the bone loss around the tooth before its removal and the bone levels on the adjacent teeth have been compromised prior to tooth removal.

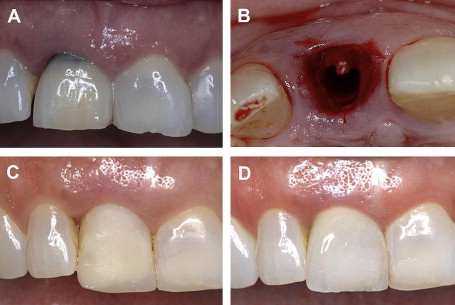

The facial gingival margin level will also be influenced by the methods used immediately after tooth removal. In an clinical trial supported by the National Institutes of Health, it was found that placing an abutment immediately on the implant at time of implant placement at the same time as tooth removal resulted in more facial gingival tissue preservation as compared with a delayed procedure. Patients in the delayed group had the tooth removed and the socket grafted. After 4 months elapsed, the implant was placed with a provisional restoration. In this group the facial gingival margin was 1 mm more apical compared with the immediate provisionalized group. The immediate provisionalized group had the tooth removed with immediate implant and provisional crown placement. The immediate provisionalized group had 1 mm more coronal tissue than the delayed group.

Based on the foregoing discussion, an algorithm for treatment can be formed ( Figs. 1–4 ).

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses