Oral and maxillofacial surgeons use in-office anesthesia techniques on a daily basis more than any other specialty outside anesthesiology. Despite the magnitude of the number of patients who receive deep sedation and general anesthesia in oral and maxillofacial surgeons’ offices every year, the mortality is low, attesting to the skill and safety vigilance of the specialty. Nevertheless, complications are inevitable and urgent or emergent issues need to be anticipated. Therefore, competence in airway evaluation and management of the difficult airway are essential skills for the oral and maxillofacial surgeon.

Difficult or failed airway management during untoward events accounts for most anesthesia-related morbidity and mortality, and there is no one test to determine a patient’s risk of airway compromise while undergoing general anesthesia . Instead, multiple considerations must be taken into account when evaluating and treating each patient. Because airway compromise can lead to rapid decompensation of the patient, thorough evaluation and competent knowledge of how to approach a difficult airway allow swift action when complications in airway management occur, potentially alleviating a life-threatening situation.

What is a difficult airway?

There is no one accepted definition of a difficult airway, but instead the difficult airway generally comprises a set of factors including inadequacy of ventilation using a facemask, inability to visualize the vocal cords with a laryngoscope, difficulty or inability to intubate with standard endotracheal tubes, or the need to use surgical means to establish an airway. The level of difficulty may be altered by the patient’s health status, airway anatomy, or the surgical procedure that is being performed. The goal for the oral and maxillofacial surgeon is to evaluate the difficult airway thoroughly preoperatively and correlate these findings with a potential difficult airway to prevent complications during anesthesia.

Airway evaluation

Because of the number and variety of procedures that are performed in close proximity to the airway, many patients undergoing oral and maxillofacial surgery present special challenges with anesthesia and airway protection. It is imperative, therefore, that any patient undergoing nonemergent anesthesia in an office or operating-room setting should have a complete history and airway physical examination to identify and attempt to prevent any airway compromise. Important questions include difficulties with anesthesia in the past, family history of difficult anesthesia, and a current list of all medications being taken. If there is a history of prior anesthetic problems, the oral and maxillofacial surgeon should request anesthesia records to identify which airway management techniques were used and if the results were optimal for the patient’s treatment. Other factors that may lead to difficult airway management and are important to include in the preoperative evaluation include a history of sleep apnea, snoring, or head and neck abnormalities .

Many preoperative physical examinations have been developed to predict the possibility of a difficult airway. Individually, these tests may not be sensitive or specific enough to use independently, but in combination they may be used to quantify a patient’s risk of undergoing anesthetic procedures . These tests include the Mallampati classification, thyromental distance, sternomental distance, and maximum vertical opening (MVO).

Mallampati score

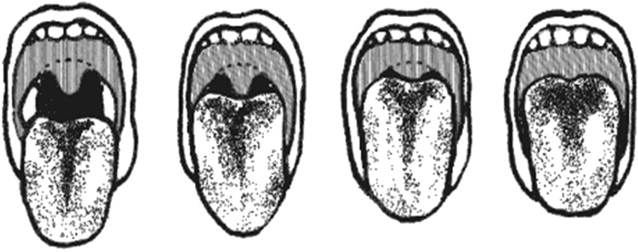

The Mallampati classification system was developed to relate the oropharyngeal space with the ease of direct laryngoscopy by rating the shape of the palate and the displacement of the tongue . This test also assesses if the MVO is large enough to permit intubation. To perform the test, the examiner observes the patient at eye level and asks the patient to open the mouth maximally and protrude the tongue without phonating. The examiner then classifies the airway according to the structures that are visible in the pharyngeal area. In a class I airway the soft palate, fauces, uvula, and tonsillar pillars are visible; in class II the soft palate, fauces, and uvula are visible; in class III the soft palate and base of uvula are visible; and in class IV only the hard palate is visible ( Fig. 1 ). A Mallampati score of III or greater indicates the potential for a difficult intubation and mandates additional consideration. Tuzuner-Oncul and Kucukyavuz evaluated difficult intubations in 208 oral and maxillofacial surgery patients and concluded that a Mallampati score of III or IV related to a sensitivity of 59% and a specificity of 83% for the prediction of difficult intubation.

Thyromental distance

The thyromental distance is believed to be an indicator of the ability to displace the tongue during attempted direct visual laryngoscopy (DVL) and is therefore a marker for the amount of mandibular space available . The thyromental distance is measured with the patient lying supine with the head fully extended and the mouth closed. A ruler measures the straight line distance from the thyroid notch to the lower border of the mentum. A distance of 6.5 cm or less is a predictor of a difficult airway as it is usually seen in patients with retrognathia or a short neck . This creates the inability to visualize the larynx during tracheal intubation ( Fig. 2 ). This test can be performed simply at the bedside without a ruler by estimating the number of fingerbreadths between the thyroid and the mentum. Three fingerbreadths or more is usually consistent with the ability to visualize the larynx during DVL ( Fig. 3 ).

Sternomental distance

The sternomental distance is classified as an indicator of head and neck mobility. It is measured with the patient’s head in full extension from the sternal notch to the bony menton ( Fig. 4 ). During airway evaluation a patient who has less than 12.5 cm sternomental distance may not have the neck flexibility to be placed in the proper position for ventilation or oxygenation . The proper alignment about the atlantooccipital joint when the neck is extended places the axes of the larynx, pharynx, and mouth so they are almost parallel: the so-called sniffing position ( Fig. 5 ). This sniffing position increases the success rate of DVL and the ability to establish a secure airway .

MVO

Because the oropharyngeal airway is generally the main access point for ventilation in an emergency, an interincisal distance of less than 30 mm is considered to add potential difficulty to airway management. Trismus, infection, tumors, and temporomandibular joint (TMJ) disorders are encountered by the oral and maxillofacial surgeon regularly and can severely limit the MVO. Once general anesthesia has been induced with muscle relaxation, patients who have a condition in which pain limits the ability to open will have an increase in MVO. On the other hand, when a true mechanical obstruction exists, the practitioner must be prepared with alternative airway options, as even paralyzed patients may not open their mouth sufficiently for placement of a laryngoscope.

Airway evaluation

Because of the number and variety of procedures that are performed in close proximity to the airway, many patients undergoing oral and maxillofacial surgery present special challenges with anesthesia and airway protection. It is imperative, therefore, that any patient undergoing nonemergent anesthesia in an office or operating-room setting should have a complete history and airway physical examination to identify and attempt to prevent any airway compromise. Important questions include difficulties with anesthesia in the past, family history of difficult anesthesia, and a current list of all medications being taken. If there is a history of prior anesthetic problems, the oral and maxillofacial surgeon should request anesthesia records to identify which airway management techniques were used and if the results were optimal for the patient’s treatment. Other factors that may lead to difficult airway management and are important to include in the preoperative evaluation include a history of sleep apnea, snoring, or head and neck abnormalities .

Many preoperative physical examinations have been developed to predict the possibility of a difficult airway. Individually, these tests may not be sensitive or specific enough to use independently, but in combination they may be used to quantify a patient’s risk of undergoing anesthetic procedures . These tests include the Mallampati classification, thyromental distance, sternomental distance, and maximum vertical opening (MVO).

Mallampati score

The Mallampati classification system was developed to relate the oropharyngeal space with the ease of direct laryngoscopy by rating the shape of the palate and the displacement of the tongue . This test also assesses if the MVO is large enough to permit intubation. To perform the test, the examiner observes the patient at eye level and asks the patient to open the mouth maximally and protrude the tongue without phonating. The examiner then classifies the airway according to the structures that are visible in the pharyngeal area. In a class I airway the soft palate, fauces, uvula, and tonsillar pillars are visible; in class II the soft palate, fauces, and uvula are visible; in class III the soft palate and base of uvula are visible; and in class IV only the hard palate is visible ( Fig. 1 ). A Mallampati score of III or greater indicates the potential for a difficult intubation and mandates additional consideration. Tuzuner-Oncul and Kucukyavuz evaluated difficult intubations in 208 oral and maxillofacial surgery patients and concluded that a Mallampati score of III or IV related to a sensitivity of 59% and a specificity of 83% for the prediction of difficult intubation.

Thyromental distance

The thyromental distance is believed to be an indicator of the ability to displace the tongue during attempted direct visual laryngoscopy (DVL) and is therefore a marker for the amount of mandibular space available . The thyromental distance is measured with the patient lying supine with the head fully extended and the mouth closed. A ruler measures the straight line distance from the thyroid notch to the lower border of the mentum. A distance of 6.5 cm or less is a predictor of a difficult airway as it is usually seen in patients with retrognathia or a short neck . This creates the inability to visualize the larynx during tracheal intubation ( Fig. 2 ). This test can be performed simply at the bedside without a ruler by estimating the number of fingerbreadths between the thyroid and the mentum. Three fingerbreadths or more is usually consistent with the ability to visualize the larynx during DVL ( Fig. 3 ).

Sternomental distance

The sternomental distance is classified as an indicator of head and neck mobility. It is measured with the patient’s head in full extension from the sternal notch to the bony menton ( Fig. 4 ). During airway evaluation a patient who has less than 12.5 cm sternomental distance may not have the neck flexibility to be placed in the proper position for ventilation or oxygenation . The proper alignment about the atlantooccipital joint when the neck is extended places the axes of the larynx, pharynx, and mouth so they are almost parallel: the so-called sniffing position ( Fig. 5 ). This sniffing position increases the success rate of DVL and the ability to establish a secure airway .

MVO

Because the oropharyngeal airway is generally the main access point for ventilation in an emergency, an interincisal distance of less than 30 mm is considered to add potential difficulty to airway management. Trismus, infection, tumors, and temporomandibular joint (TMJ) disorders are encountered by the oral and maxillofacial surgeon regularly and can severely limit the MVO. Once general anesthesia has been induced with muscle relaxation, patients who have a condition in which pain limits the ability to open will have an increase in MVO. On the other hand, when a true mechanical obstruction exists, the practitioner must be prepared with alternative airway options, as even paralyzed patients may not open their mouth sufficiently for placement of a laryngoscope.

Other factors to consider in anesthesia evaluation

Along with the preoperative tests that objectively evaluate a difficult airway, the oral and maxillofacial surgeon must also consider the overall body habitus of the patient and note any congenital or pathologic conditions that could influence and alter airway management ( Tables 1 and 2 ). The obese patient requires special consideration during airway evaluation; the overweight patient has a decreased functional residual capacity, desaturates oxygen stores rapidly, and may have difficulty with mask ventilation . Obesity is also associated with a decrease in posterior airway space, which increases the risk factors for obstructive sleep apnea . In a clinical review of the management of difficult airways, Langeron and colleagues found that in obese and morbidly obese patients (body mass index [BMI] calculated as weight in kilograms divided by the square of height in meters >30 kg/m 2 and >40 kg/m 2 , respectively) the risk of oxygen desaturation during induction of anesthesia and the risk of difficult intubation are increased significantly.