The mid-face is a complex anatomic region consisting of the maxilla and its multiple complex articulations with the adjacent upper and lower facial skeleton. The maxilla helps form the oral cavity, orbit, and nasal cavity; connects the cranial base with the occlusal plane; and allows proper anterior projection of the face. The maxilla along with the rest of the mid-face consists of multiple thickened buttresses running vertically, sagittally, and transversely that provide support for the underlying air-filled sinuses. The buttresses are protective against superior forces but are vulnerable to frontally and laterally directed forces.

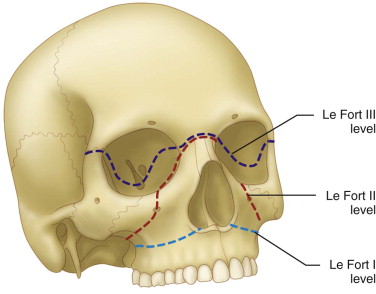

René Le Fort famously characterized the types of fractures occurring in the mid-face with force directed anteriorly. It is rare that fractures obey the classifications set forth by Le Fort. Classifications do, however, serve as a guide for systematic diagnosis and subsequent treatment ( Fig. 41-1 ).

Etiopathogenesis/Causative Factors

Le Fort fractures rarely occur in isolation but, instead, are frequently seen in conjunction with other facial fractures. Patients may also have lacerations and orthopedic or neurologic injuries. As with other facial fractures, they are most common in young men aged 16 to 40 years.

Pathologic Anatomy

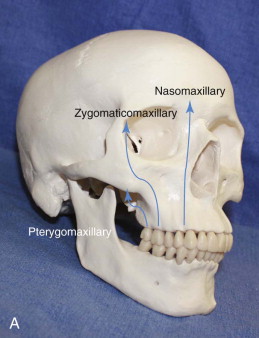

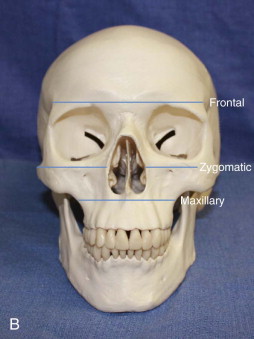

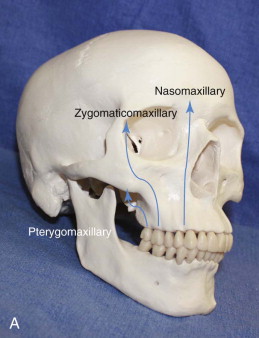

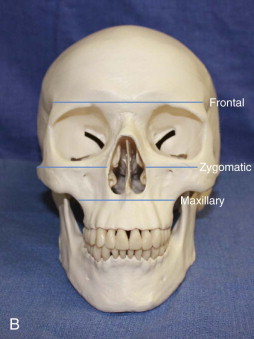

Le Fort fractures involve multiple bones of the mid-face, including the maxilla, nasal bone, lacrimal bone, ethmoid, palatine bone, vomer, sphenoid, and zygoma. The maxilla is the largest bone involved in these fractures and actually consists of two bones that are fused at the midline and serve to attach the skull base to the lower part of the face. It has articulations with the frontal, lacrimal, nasal, inferior concha, vomer, sphenoid, ethmoid, palatine, and zygomatic bones. Each maxilla consists of a body and frontal, zygomatic, palatine, and alveolar processes. Through its articulations with the rest of the mid-face, the maxilla helps form three of the vertical buttresses of the face. The nasomaxillary buttress includes the lateral piriform rim and, superiorly, the frontal process of the maxilla and the maxillary process of the frontal bone. The zygomaticomaxillary buttress runs from the frontal bone superiorly along the lateral orbital rim, including the zygoma and zygomatic process of the maxilla. The pterygomaxillary buttress includes the pterygoid plates of the sphenoid and maxillary tuberosity and establishes posterior facial height along with the mandibular condyle-ramus unit ( Fig. 41-2, A ). The horizontal buttresses are the frontal, zygomatic, maxillary, and mandibular buttresses. The frontal buttress consists of the superior orbital rim, and the zygomatic buttress consists of the zygomatic arch and body of the zygoma extending to the inferior orbital rim. The maxillary buttress consists of the palate at the level of the maxillary alveolus ( Fig. 41-2, B ).

Pathologic Anatomy

Le Fort fractures involve multiple bones of the mid-face, including the maxilla, nasal bone, lacrimal bone, ethmoid, palatine bone, vomer, sphenoid, and zygoma. The maxilla is the largest bone involved in these fractures and actually consists of two bones that are fused at the midline and serve to attach the skull base to the lower part of the face. It has articulations with the frontal, lacrimal, nasal, inferior concha, vomer, sphenoid, ethmoid, palatine, and zygomatic bones. Each maxilla consists of a body and frontal, zygomatic, palatine, and alveolar processes. Through its articulations with the rest of the mid-face, the maxilla helps form three of the vertical buttresses of the face. The nasomaxillary buttress includes the lateral piriform rim and, superiorly, the frontal process of the maxilla and the maxillary process of the frontal bone. The zygomaticomaxillary buttress runs from the frontal bone superiorly along the lateral orbital rim, including the zygoma and zygomatic process of the maxilla. The pterygomaxillary buttress includes the pterygoid plates of the sphenoid and maxillary tuberosity and establishes posterior facial height along with the mandibular condyle-ramus unit ( Fig. 41-2, A ). The horizontal buttresses are the frontal, zygomatic, maxillary, and mandibular buttresses. The frontal buttress consists of the superior orbital rim, and the zygomatic buttress consists of the zygomatic arch and body of the zygoma extending to the inferior orbital rim. The maxillary buttress consists of the palate at the level of the maxillary alveolus ( Fig. 41-2, B ).

Le Fort Classifications

Le Fort I

Le Fort I fractures result from a force directed above the dentoalveolar segment of the maxilla. The fracture generally courses from the piriform aperture posteriorly through the anterior and lateral wall of the maxillary sinus, the maxillary tuberosity, and the pterygoid plates. The fracture also often includes the nasal septum and it may disrupt the septal cartilage. The mobile segment includes the entire dentoalveolar segment and palate, including the palatine bone and the lower third of the pterygoid plates. The lateral and medial pterygoid muscles often remain attached to the pterygoid plates and maxillary tuberosity and pull the segment posteriorly and inferiorly. The patient may have an anterior open bite ( Fig. 41-3 ).

Le Fort Ii

A Le Fort II fracture results from a somewhat more superior force directed at the nasal bones. The pyramidally shaped central mid-face is separated from the rest of the facial skeleton and skull base. The fracture line extends from the nasofrontal suture through the nasal and lacrimal bones to the zygomaticomaxillary suture along the orbital floor. The fracture then continues along the zygomaticomaxillary suture inferiorly to the maxillary tuberosity and through the pterygoid plates. The fractured segment includes the entire maxilla, the nasal bones, the medial third of the orbital rim, the nasal septum, the palatine bones, the dentoalveolar segment, and the inferior portion of the pterygoid plates.

Le Fort Iii

With a force directed at the level of the orbit, a Le Fort III fracture can occur and result in craniofacial disjunction. The fracture passes through the nasofrontal region along the medial orbit through the superior and inferior orbital fissures and then along the lateral orbital wall through the frontozygomatic suture. The fracture then extends through the zygomaticotemporal suture and inferiorly through the sphenoid bone and pterygomaxillary fissure. The zygoma, maxilla, palatine bones, and nasal bones, including the entire septum, are separated from the cranial base.

Diagnosis

After initial resuscitation and stabilization of the trauma patient, a complete head and neck physical examination is performed as part of the secondary survey. The patient’s head and neck are inspected for asymmetry, laceration, ecchymosis, and discharge from the nose or ears. For detection of mid-face fractures, the examiner should systematically and bimanually palpate the frontal bones, including the supraorbital rims and the nasofrontal suture. Evaluation should then proceed along the lateral orbital rims and zygoma, including the zygomatic arch. The maximum incisal opening is noted, and the intraoral examination includes assessment of the maxillary vestibule, zygomaticomaxillary buttresses, and palate. The maxillary and mandibular arch should be evaluated for occlusal step-offs and malocclusions. One should assess for mobility of the maxilla at the three Le Fort levels by pulling forward on the anterior aspect of the alveolar process while palpating the nasal bridge and zygomaticofrontal sutures with the opposite hand.

Radiographs are obtained to confirm the clinical findings. Computed tomography (CT) is now the most frequently used technique for identifying fractures in the mid-face. A directed maxillofacial CT scan with fine cuts (1 mm or less) should be obtained. In addition to axial views, coronal and sagittal views are required to assess the orbits and nasoethmoid region.

Certain radiographic patterns are very helpful in properly diagnosing Le Fort fractures. In all three levels of Le Fort fractures, a pterygoid plate fracture is seen. The finding of a pterygoid plate fracture unilaterally or bilaterally should alert the clinician to the possibility of a Le Fort fracture ( Fig. 41-4 ). Each Le Fort fracture level has one unique fracture different from the other two levels. For Le Fort I, a fracture is seen through the lateral aspect of the piriform aperture. Only Le Fort II includes a fracture of the inferior orbital rim and zygomaticomaxillary buttress. Le Fort III fractures are the only level to contain fractures of the lateral orbital wall and zygomatic arch. Again, combinations of different levels bilaterally or even multiple levels on each side only complicate the radiographic diagnosis ( Fig. 41-5

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses