Interprofessional collaborative practice (IPC) is paramount to the future of oral health education. As such, it is critical that today’s health care education continues to expand its curriculum to promote oral health as an essential component in the IPC approach to women’s health. This article explores models that can be implemented using an IPC framework to foster better approaches in the delivery of care to female patients.

Key points

- •

Oral disease is among the most prevalent health problems, and discrepancies that exist regarding the health of women compared with the health of men.

- •

Five key concepts for women’s oral health using an interprofessional collaborative framework include wellness and prevention, biologic applications, selective disease awareness, behavioral health, and interprofessional health team members’ roles.

- •

An interprofessional collaborative team approach increases awareness among oral health care providers, along with obstetrician/gynecologists, regarding the significance of oral health during pregnancy.

- •

The oral health care provider is central to an interprofessional collaborative framework in identifying victims of intimate partner violence, as most injuries are facial and intimate partner violence exposure results in poor health.

- •

Providing interprofessional collaborative models involving both oral and overall health care professionals enable patient-centered care with patients becoming more empowered in decision making.

Introduction

The US Surgeon General issued a report calling attention to the “silent epidemic” of dental and oral diseases suffered by millions of children and adults throughout the United States. The report called for the development of a National Oral Health Plan that would “improve quality of life and eliminate health disparities by facilitating collaborations among individuals, health care providers, communities, and policymakers at all levels of society and by taking advantage of existing initiatives.” As a result, there is now an emphasis on examining the relationship of poor oral health and its influence on systemic disease. The latter lends support for an interdisciplinary collaboration of health care professionals including the oral health care provider, in comprehensive patient care to eradicate dental health disparities and health disparities in general.

The above collaborative effort has driven a model for innovative interprofessional collaborative (IPC) practice with respect to the oral and overall health of women. Women engage with a wide array of providers across their lifespan, often interacting more frequently with health providers compared with men; therefore, women’s health can be an ideal area in which to pursue further IPC strategies. The US Department of Health and Human Services, Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA), Office of Women’s Health in 2013, commissioned a report that provided recommendations to improve women’s health education across 5 specific health professions programs: medicine, oral health/dentistry, baccalaureate nursing, pharmacy, and public health. Both women’s health and IPC practice are top priorities in health education, and improvements may contribute to dramatic health benefits across the population. This article provides the reader with several examples of IPC frameworks/models designed to provide oral health care practitioners skills to enhance their role within the interprofessional team approach to the care of the female patient. The authors chose several important health disparities that have both oral and systemic manifestations that can be approached using an IPC paradigm.

Women’s Overall Health Needs

The Institute Of Medicine mandated that there was a need to integrate dentistry with medicine and the health care system as a whole to provide greater research support of an oral-systemic health connection. These changes in health care delivery and the reports on new health care models have helped shape the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act, signed into law in 2010, which proposes to improve and promote “A Healthier Nation,” encompasses the ideals of interprofessional collaboration. It has recreated health care for all by addressing the quality of health care, the costs, and, most important, the advent of access to care for all.

The hypothesized “Triple Aim” as suggested by Donald Berwick, MD, 12 has the potential to remedy the significant expense of health care in the United States, improve outcomes, and increase the value of the health care dollars spent. The Triple Aim model of health care can have a significant impact on women, especially with the increase in Medicaid and Medicare benefits. The Centers for Medicare and Medicaid estimate that 18 million women will find insurance coverage that fits their needs in the marketplace. It is well known that women are more likely than men to require coverage, particularly during the reproductive years, and have a greater out of pocket cost; therefore, they may be unable to pay because of a concomitant wage discrepancy compared with their male cohorts. As a result of the Affordable Care Act, women are now eligible to receive not only preventive coverage for wellness visits but also examinations for specialty needs, that is, obstetrician/gynecologist (OB/GYN) visits, without requirement of a referral from their primary care doctors. This concept also creates an opportunity for professions to collaborate in providing optimal comprehensive health care that is inclusive of not only medical health needs but communicative roads toward the inclusion of oral health, treatment, and prevention.

The above concept has the potential to close the gender gap between men and women with respect to awareness of health needs that are quite separate in physiology and treatment strategies based on the disease entity. Several research groups propose different health attitudes across genders and have hypothesized a gender gap in health reporting. For instance, according to Bogner and Gallo, women are more likely to interpret symptoms associated with depression and low well-being as signs of emotional problems and hence get psychiatric help. This finding suggests that women perceive symptoms in different ways compared with men, so that they also seek more medical care. Hibbard and Pope found that women also report higher interest and concern about health than men do. The most recent studies suggest that health matters are more salient among women that they value health more than men do and that they have more responsibility in caring for ill family members. Such findings are consistent with the idea that women pay more attention to health than men do.

Women’s Health and Oral Health

Documentation continues to list oral disease as one of the most prevalent health problems and discrepancies in the health of women compared with men. As such, the oral health care component of the IPC model for women’s health is of great interest not only to women of reproductive age but to those in midlife and the elderly. Issues such as oral health changes caused by cardiovascular disease, sexuality, domestic violence, and disease prevention are all health disparities that poor oral health can impact/exacerbate. Experts in women’s health define the discipline of IPC as a product of cultural, social, and psychological factors in addition to biology. An IPC model for women’s health and men’s health can empower both the patient and their providers by identifying a comprehensive health plan that increases disease prevention and reduces health costs in the community they treat.

The approach to a new paradigm of oral health as part of overall health and well-being formed the basis for a 2011 expert panel in Washington DC to design a broad curriculum that melded dentistry, medicine, pharmacy, nursing, osteopathic medicine, and public health. A framework was crafted to develop core competencies for an interprofessional educational collaborative (IPEC) with a common goal for an interdisciplinary approach to total patient health. This expert panel defines interprofessional teamwork as “the levels of cooperation, coordination and collaboration characterizing the relationships between professions in delivering patient-centered care and interprofessional team-based care … and shared responsibility for a patient or group of patients.” The report from this panel defines 4 broad domains of competency: values and ethics, roles and responsibilities, interprofessional communication, and, most importantly, team-based care. The competencies are framed around the concept that health care should be patient/family centered, community/population oriented, relationship focused, and process oriented.

Community Models that Apply Oral Health Within an Interprofessional Collaborative Framework

The impact of IPC teamwork on the health needs of women is exemplified in the community models described below. The utilization of IPC frameworks in each model described integrates the interdisciplinary voices of both health care providers and patients to reinforce comprehensive health habits and empower better decision-making strategies for the health and well-being of women. The health issues discussed include the care of pregnant women, women who have experienced domestic violence/intimate partner violence (IPV), and women with chronic diseases in their elderly years.

Interprofessional collaborative model for oral/overall health during pregnancy

It is estimated that 6.5 million women in the United States become pregnant each year. The physiologic changes that occur during pregnancy caused by hormonal changes are necessary to support and safeguard the developing fetus and prepare the mother for parturition. These systemic changes can also affect the woman’s oral health. Dental problems not only cause pain and discomfort but also can be a risk factor for preterm delivery and low birth weight babies. Although there are standardized guidelines for health care professionals providing prenatal care, studies do not show that most health professionals providing prenatal care incorporate oral examinations as part of standard prenatal care. As such, the IPC team approach is paramount among the OB/GYN and other health professionals (eg, dentists, dental hygienists, physicians, nurses, midwives, nurse practitioners, physician assistants) to provide pregnant women with appropriate and timely oral health care, which includes oral health education. Based on this principle, numerous health care organizations have fostered efforts to promote oral health for pregnant women. The American Academy of Pediatric Dentistry, the American Academy of Pediatrics, the American Academy of Periodontology, the American Academy of Physician Assistants, the American College of Nurse-Midwives, the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, and the American Dental Association (ADA) have issued statements and recommendations for improving oral health care during pregnancy. An expert panel was convened to develop an Oral Health Care During Pregnancy Consensus Statement through a Development Expert Workgroup Meeting in 2011 convened by HRSA’s Maternal and Child Health Bureau (MCHB) in collaboration with American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists and ADA and coordinated by the National Maternal and Child Oral Health Resource Center. The implementation within this statement would bring about changes in the health care delivery service to women during pregnancy and thereby improve the overall standard of care. Box 1 describes the key points of the 2012 Consensus Statement.

- •

Assess pregnant woman’s health status and when to consult with prenatal health professional.

- •

Advise pregnant woman about oral health care and safety of dental treatment during pregnancy.

- •

Work in collaboration with oral health care professionals.

- •

Provide support services (social services) to pregnant women.

- •

Improve health services in the community.

- •

Assess pregnant woman’s oral health status.

- •

Advise pregnant women about oral health care.

- •

Improve health services in the community.

Based on the above approach, a community model was developed to encourage an IPC framework that examines oral health during pregnancy.

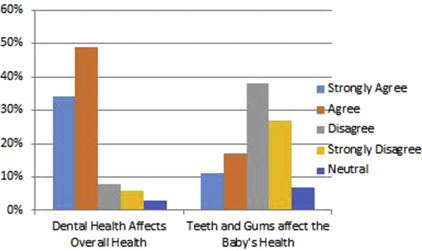

Model

A pilot study called An Interprofessional Education Approach to Increasing Access to Health Services for African American Women at Risk for Preterm-Low Birth Weight Babies (funded by the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation Center for Health Policy, Meharry Medical College, Nashville, TN) was designed to increase access to health services and improve oral health/overall health through an IPC approach. The women in the project were seen in the Meharry Dental School, Meharry Center for Women’s Health Clinics (OB/GYN, Meharry Centering Pregnancy), Matthew Walker Community Health Center, Meharry 1919 Clinic, and one private OB/GYN office. The target population was African-American women at risk for preterm low birth weight babies. The participants were recruited from the centers listed above and administered a validated survey to assess their awareness, knowledge, and attitude regarding oral health as it relates to adverse pregnancy outcomes ( Tables 1 and 2 ). A total of 159 surveys were collected with completed data analyzed on 146 participants (95%). The study concluded that the stronger the participant’s perception that their dental health affects their overall health, the more strongly they agreed that their teeth and gums would affect whether their baby is healthy ( Fig. 1 ). The results of the data analysis also suggested that insurance status, household income, and type of insurance impacted participants’ perceptions of regular dental check-ups, of dental health on overall health, and the impact of their oral health on the health of their baby. The IPC team (dentist, dental hygienists, OB/GYN physicians, maternal fetal medicine physicians, nurse midwife, nurse practitioner, social worker, behaviorist, nutritionist, physician assistant, and other health care providers) participated in training workshops and seminars and shared values of delivering the message of preventive care to pregnant women to optimize birth outcomes. The goal was to instill in the pregnant patient the importance of seeking dental care as part of their prenatal care (Thompson and Farmer-Dixon, 2015).

| The information that you provide will help us to identify ways in which we can better take care of your oral health in an effort to reduce your chance for adverse pregnancy outcomes. Please answer questions about your feelings and experiences. There are no right or wrong answers. Your answers will be strictly confidential. Please do not write your name, or any other identifiable information on this form. Thank you for your help in this important effort to improve your overall health. | |||||

| Instructions: For each of the following questions, please check the appropriate answer or circle the number that indicates your level of agreement or disagreement. | |||||

| General Information | |||||

|

|||||

| Agree | Strongly Agree | Disagree | Strongly Disagree | Not applicable | |

| About the Health of your Mouth | |||||

|

5 | 4 | 3 | 2 | 1 |

|

5 | 4 | 3 | 2 | 1 |

|

5 | 4 | 3 | 2 | 1 |

|

5 | 4 | 3 | 2 | 1 |

|

5 | 4 | 3 | 2 | 1 |

|

5 | 4 | 3 | 2 | 1 |

|

5 | 4 | 3 | 2 | 1 |

|

5 | 4 | 3 | 2 | 1 |

|

5 | 4 | 3 | 2 | 1 |

|

5 | 4 | 3 | 2 | 1 |

|

5 | 4 | 3 | 2 | 1 |

|

5 | 4 | 3 | 2 | 1 |

|

5 | 4 | 3 | 2 | 1 |

| Access to the Dental Clinic (Meharry Dental Clinic or Matthew Walker Dental Clinic) | |||||

|

5 | 4 | 3 | 2 | 1 |

|

5 | 4 | 3 | 2 | 1 |

|

5 | 4 | 3 | 2 | 1 |

|

5 | 4 | 3 | 2 | 1 |

|

5 | 4 | 3 | 2 | 1 |

|

5 | 4 | 3 | 2 | 1 |

|

5 | 4 | 3 | 2 | 1 |

|

5 | 4 | 3 | 2 | 1 |

|

5 | 4 | 3 | 2 | 1 |

|

5 | 4 | 3 | 2 | 1 |

|

5 | 4 | 3 | 2 | 1 |

|

5 | 4 | 3 | 2 | 1 |

| General Information continued | |||||

|

5 | 4 | 3 | 2 | 1 |

|

5 | 4 | 3 | 2 | 1 |

|

5 | 4 | 3 | 2 | 1 |

|

|||||

|

|||||

|

|||||

|

|||||

|

|||||

| Demographic Information | |||||

|

|||||

|

|||||

| Thank you for your participation. | |||||

| Variables in Equation | Regression Coefficients | P Value |

|---|---|---|

| Question 1: Perception of Regular Dental Checkups | 0.064 | .426, NS |

| Question 11: Perception That Dental Health Affects Overall Health | 0.519 | .000 a |

| Question 30A: Insurance Status | 0.009 | .907, NS |

| Question 35: Yearly Household Income | 0.028 | .743, NS |

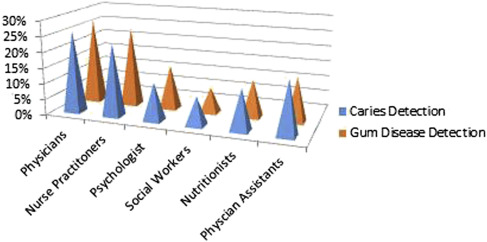

The results of this pilot study suggest “there is a relationship between oral health during pregnancy and overall health.” The IPC team, however, felt that education was lacking in familiarity with dental caries detection/gum disease and the role they could play in addressing oral health care needs within this patient population (physicians <30%; nurses ≤25%; physician assistants ≤17%; Fig. 2 ). IPC dialogue and education are still needed to build strong partnerships for patient-centered care in the management of oral health during pregnancy.

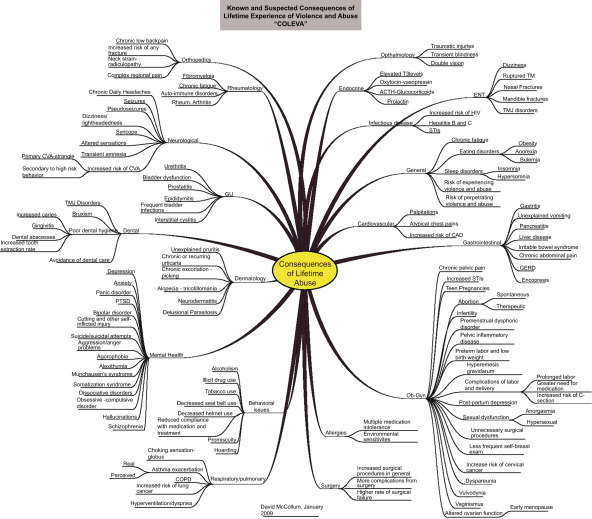

Interprofessional collaborative model for intimate partner violence identification/intervention

Violence and abuse is a serious global public health epidemic. A multicountry study by the World Health Organization found that 25% to 50% of women interviewed reported physical assaults that resulted in injuries and, as a result, have poor health and want to commit suicide. Studies propose a strong statistical association between IPV and adverse health outcomes. As such, violence and abuse have serious long-term medical consequences that last long after the initial trauma with a higher utilization of health services compared with matched cohorts who were not abused ( Fig. 3 ). Within the United States, health care invests billions of dollars yearly treating the consequences of abuse—too often without addressing the underlying causes. Numerous health care bodies (AMA, Institute of Medicine, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, ADA) recommend that all patients be asked routinely about abuse. Early diagnosis of IPV-related injuries would significantly improve the health of victims and save billions of dollars in health care costs.

Violence/Abuse Oral Health/Interprofessional Collaborative Paradigm

The gold standard for identifying an IPV-related injury is the patient’s self-report, and, therefore, the diagnosis can be challenging. The health care sector in general has identified and cared for victims of violence and abuse after the fact and are often in a quandary with respect to “igniting the process,” that is, identify and intervene in IPV and domestic violence patient populations. Within specialties, there are protocols but no commonly agreed on written guidelines for reasons such as litigation and personal experience. With the above in mind, a solution requires that various health providers work together using an IPC approach to not only recognize the epidemic but also integrate a common language of guidelines that can be used uniformly in all health care settings to identify victims and provide intervention.

IPV is a frequent cause of facial injuries in victims between the ages of 18 and 64 with 75% of cases resulting in injuries to the head, neck, or mouth. The residual effects of scars, facial asymmetries, damage to dentition, loss of masticator function, and psychological wounds persist to remind injured women the level of control by the perpetrator. With greater than 50% of adults and children visiting the dentist, oral health care provides a pivotal point of contact for IPV victims. Few reports, however, specify the causes or patterns of orofacial injuries in victims with IPV-related injuries using benign tools that encourage identification. A paucity of studies have addressed health and social problems with regard to the interprofessional model and how the oral health care provider can be a significant link in this interdisciplinary chain of identifying and preventing future injuries in victims. The following are examples of community approaches using an IPC framework with oral health as a major link in the chain of identifying victims of violence and abuse for referral/intervention.

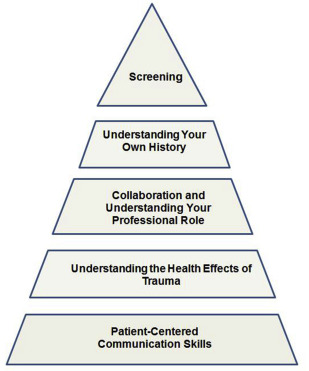

Model 1: Trauma-informed care approach

Raja and colleagues suggest an oral health model to provide a framework for identification and referral of patients exposed to traumatic events. Their concept of trauma-informed care developed from experiences by oral health care providers that treat patients with a history of traumatic events at one point only but lack the tools for monitoring the survivors they identify over a longer period. Dental patients with a history of traumatic experiences are more likely to engage in negative health habits and to display fear of routine dental care. Although not all patients disclose a trauma history to their dentists, some patients might. The trauma-informed care pyramid provides a framework to guide dental care providers in interactions with many types of traumatized patients using behavioral and communication skills as well as understanding the health effects of trauma and understanding how the provider’s own trauma-related experiences can influence treatment strategies within an IPC framework. Fig. 4 depicts this approach, which is built on a foundation of patient communication, health effects of trauma, and the need for IPC collaboration. This pyramid can be universally applied in an IPC framework across all health disciplines.

Model 2: From family violence to health: an oral health approach at Dalhousie University

At Dalhousie University in Canada, dental and other health faculty crafted an IPC module that features the role of dental health professionals as central in the identification of victims of abuse. The model hypothesizes the need for dental health care providers to work collaboratively with their medical, social, and legal colleagues to identify and eradicate domestic violence and IPV. This is approached from a predoctoral perspective first followed by interdisciplinary communication via interdisciplinary focus groups. Outcomes measurements are based on qualitative parameters in which the provider becomes aware of clinical presentations of violence and abuse within the oral cavity and its effect on victims, that is, “What is the role of oral health in family violence? How might health professionals work together to allow for a better health-related quality of life in the community of victims.” Quantitative risk predictors include a Likert scale approach with mean score measurements that allowed a better understanding of other health professional roles/ways to complement each other’s approach to this problem and work in a health team environment that embraces cross-professional understanding for total patient care. Cross-discipline continuing education reinforces the IPC framework with regular follow-up on the outcomes measured within the interdisciplinary sphere of their health arena by feedback analyses.

Model 3. Interprofessional collaborative model of violence and abuse survivors: early and long-term outcomes

Women experience more IPV than men; 4.8 million rapes and greater than 2 million injuries are enough to require multiple forms of health care (emergency room, dental care, hospital stays, and physical/psychological therapies). The health care sector traditionally cares for victims after the fact due to the induced physical and mental health injuries. As such, the main precedence for the health care sector to address this dilemma is to develop best practice approaches that are not only team based but also aligned for rapid response to prevent further collateral damage. Wilson and Websdale crafted a paradigm “Domestic Violence Fatality Review Team” (DVFRT) the purpose of which is to provide strategies that prevent future injuries, ensure safety, and hold perpetrators and the system responsible. This approach is unique because of the diversity of their team membership and more importantly because of the knowledge, experience, commitment, and goal to eradicate this chronic and sometimes fatal public health issue. The DVFRT holds the professionals, agencies, and judicial system accountable and prepares an in-depth report that is disseminated through publications, conference presentations, training, and interdisciplinary educational modules. Outcome measurements include homicide surveillance data that can examine patient demographics with respect to exposure to health care, such as, oral health and medical records, ethnicity, culture, gender, and the perpetrator’s relationship to the victim. Within the United states, several regions in the east and west have used the DVFRT reports as a cursory screening tool that alerted several health and social agencies to rethink their interventional strategies and compliance protocols, which were outdated and in need of interdisciplinary revision. Many states are now using DVFRT members to formulate new professional guidelines using oral health care providers as a strong link in a chain of survival for victims of violence and abuse. Challenges, however, do remain, as the “silo” paradigm is still quite alive. Drawing on the disciplines of oral health, other health specialties, criminal justice, social services, and health policy advocates, these teams uncover basic knowledge about causation, risk, and prevention and then collectively recommend best practice patterns that offer better services and interventions to reduce future injuries and death of victims.

Model 4: Facial injuries and health consequences as risk predictors for intimate partner violence exposure: Interprofessional collaborative intervention in a Tennessee community dental center

Tennessee is the fifth in the nation with respect to the number of women who are murdered each year from abuse. Although white (non–African American [non-AA]) victims accounted for as much as 80% of victims “who reported the incident,” AA women were 3.4 times more likely to be victims compared with their non-AA cohorts. Tennessee loses at least $10 million per year in paid work time and $33 million in health care costs because of IPV, whose identification often carried out, at least in part, in an emergency room setting. Meharry Medical College (MMC) School of Dentistry in Nashville began to frame an IPC approach that uses facial injury location and questionnaires as risk predictors for identifying women with present or past exposure of IPV and uncovering those who would benefit by the health provider’s awareness of exposure to this harsh life event, how it manifests itself with poor health, and how to prevent future injuries. The School of Dentistry group composed of oral health care providers and behavioral scientists are characterizing the correlation among exposure of IPV-related injuries with specific health outcomes that affect female victims (ages18–64). The group has contrasted (1) physical findings, that is, injury location (head, neck, and facial [HNF]) versus other injuries; (2) patient responses to an IPV screening questionnaire (Partner Violence Screen [PVS]); and (3) patient responses to a general health questionnaire to characterize significant health disparities secondary to exposure of IPV in women who visit the Oral Surgery Clinic at the MMC School of Dentistry. Preliminary data support HNF injuries and positive response to the PVS screen to be statistically significant as predictors of a present or past IPV injury etiology ( P <.001) as supported by previous studies. Significant differences exist with respect to health disparities between IPV-positive/IPV-negative cohorts ( Table 3 ). IPV-positive AA women, when compared with their non-AA IPV-positive cohorts, have statistically significant differences in health consequences ( Table 4 ). The results of this pilot study are the first to identify the prevalence of IPV positivity in female AA versus non-AA dental patients at MMC School of Dentistry. HNF injuries and positive response to the PVS are statistically significant as predictors of a present or past IPV injury etiology ( P <.01). Significant differences exist with respect to health consequences between IPV-positive/IPV-negative. AA women when compared with non-AA cohorts have statistically significant differences in poor health. These preliminary results suggest the potential application of this protocol in screening programs to not only identify victims of IPV but also monitor their overall health and intervention to prevent future injuries in this health-poor community. We are working with our medicine and behaviorist colleagues to work out a system for communicating how well our intervention is succeeding in this patient population with respect to improvement and eradication of their health consequences (personal communication).

| Independent Variable | IPV (PVS+) | Non-IPV (PVS-) | P Value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Relative Frequency | Percentage | Relative Frequency | Percentage | ||

| HNF injuries | 28/40 | 70.0 | 7/38 | 18.4 | .001 |

| Anxiety | 25/40 | 62.5 | 7/38 | 18.4 | .001 |

| Swollen/painful joints | 15/34 | 44.1 | 2/30 | 6.7 | .001 |

| Fatigue/tiredness | 12/34 | 35.3 | 11/30 | 36.7 | .001 |

| Difficulty hearing | 8/34 | 23.6 | 1/30 | 3.3 | .001 |

| Memory loss | 9/34 | 26.5 | 3/30 | 10.0 | .001 |

| Chest pain | 7/34 | 20.6 | 2/30 | 6.7 | .001 |

| Vaginal/pelvis pain | 3/34 | 8.8 | 0/30 | 0.0 | .001 |

| Heart palpitation | 26/34 | 76.5 | 1/30 | 3.3 | .002 |

| Upset stomach/heartburn | 20/34 | 65.0 | 8/30 | 26.7 | .002 |

| Difficulty concentrating | 20/34 | 58.8 | 6/30 | 20.0 | .002 |

| Stress/posttraumatic stress disorder | 25/40 | 62.5 | 13/38 | 34.2 | .003 |

| Independent Variable | P Value | |

|---|---|---|

| Non-AA (n = 21) | AA (n = 13) | |

| Upset stomach/heartburn | .290 | .001 |

| Difficulty concentrating | .152 | .002 |

| Loss of appetite | .363 | .003 |

| Difficulty sleeping (insomnia) | .297 | .003 |

| Difficulty hearing | .094 | .003 |

| Bladder infection | .549 | .037 |

| Heart palpitation | .006 | .170 |

| Back pain | .028 | .858 |

| Memory loss | .019 | .869 |

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses