Introduction

Sharing resources through distance education has been proposed as 1 way to deal with a lack of full-time faculty in orthodontic residency programs. To keep distance education for orthodontic residents as cost-effective as possible while retaining interaction, we developed a “blended” interactive distance learning approach that combines observation of Web-based seminars with live postseminar discussions. For the 2009-2010 academic year, a grant from the American Association of Orthodontists opened access to the blended learning experience to all orthodontic programs in the United States and Canada. The specific aims of this project were to (1) measure programmatic interest in using blended distance learning, (2) determine resident and faculty interest, (3) determine the seminars’ perceived usefulness, and (4) elicit feedback regarding future use.

Methods

Participants in this project were expected to (1) read all assigned articles before viewing a recorded seminar, (2) watch a 1 to 1.5 hour recording of an actual interactive seminar on a Web site, and (3) participate in a 30-minute follow-up discussion immediately after watching the recorded seminar either with a faculty member at the participating institution or via a videoconference with the leader of the Web-based seminar. The residents and faculty then completed surveys about the experience.

Results

Half (52%) of the 63 orthodontic programs in the United States fully participated in this project. The blended approach to distance learning was judged to be effective and enjoyable; faculty members were somewhat more enthusiastic about the experience than were residents. Most residents were not adequately prepared for the seminars (only 14% read all preparatory articles in depth); this impacted their perception of the effectiveness and enjoyability of the experience ( P = 0.0016). Prepared residents reported a greater ability to learn from the seminars ( P = 0.0035) than those who did not read, and also indicated that they were more likely to use the seminars again ( P = 0.0018). Despite feedback regarding the need for technologic improvements of the recorded seminars, such as better editing, more frequent slides, quicker pace, and improved sound quality, most residents and faculty agreed that they would like to use this approach to distance learning again.

Conclusions

Blended distance learning is an acceptable method of instruction that allows residents to access various experts, supplement traditional instructor-led training, and ease the strain of current faculty shortages. The content of the recorded seminars needs to remain evidence-based, and some technologic aspects of the recordings should be improved.

Interactive small-group discussions are accepted as the gold standard for the highest levels of graduate education, which includes postdoctoral dental specialty programs. Interactive discussions challenge graduate students to think critically about concepts presented in assigned readings. Despite their effectiveness, not all orthodontic programs have the faculty or the resources to support this type of small-group seminar interaction. Sharing resources through distance education has been proposed as an alternative method for graduate orthodontic education. As with other instruction, interaction is a key component in distance education; researchers and practitioners agree that interaction increases learning satisfaction in distance education courses.

To keep distance education for orthodontic residents as cost-effective as possible while retaining interaction, a “blended” interactive distance learning approach was developed that combines observation of Web-based seminars with live follow-up discussions. Prior studies have assessed the effectiveness of this approach, and the findings were positive. Participants in this blended learning project were expected to (1) read all assigned articles before viewing a recorded seminar, (2) watch a 1 to 1.5 hour recording of an actual interactive seminar on a Web site, and (3) participate in a 30-minute follow-up discussion immediately after watching the recorded seminar either with a faculty member at the participating institution or via a videoconference with the leader of the Web-based seminar.

For the 2009-2010 academic year, a grant from the American Association of Orthodontists opened access to the blended learning experience to all 63 orthodontic programs in the United States. Canadian schools, also offered access, chose not to participate. The specific aims of this project were to (1) measure programmatic interest in using blended distance learning, (2) determine resident and faculty interest, (3) determine the seminars’ perceived usefulness, and (4) elicit feedback regarding future use.

Material and methods

The protocol for this investigation was reviewed by the Institutional Review Board at the University of North Carolina and declared exempt under regulations covering education-based research. Twenty-five interactive seminars in 4 topic sequences that are part of the didactic curriculum for orthodontic residents (Growth and Development, Advanced Diagnosis and Treatment Planning, Advanced Biomechanics, and Sequellae of Treatment) were recorded during actual classroom sessions at the University of North Carolina or at Ohio State University. At both schools, 2 hours were allotted for these seminars so that there would be ample time for discussion, and the expected duration was between 1.5 and 2 hours. As previously described by Miller et al, all recordings were made and processed at the University of North Carolina. All orthodontic programs in the United States were initially invited to use the educational materials via mail and e-mail; nonresponding departments received follow-up phone calls to further increase participation.

An evaluation of the perceived usefulness of this didactic method and an assessment of interest in using it in orthodontic residency education were the primary objectives of this study. Residency programs were designated as “fully participating” if they requested a registration code, at least some seminars were watched, and a follow-up survey was completed. If a residency program initially requested a registration code but did not either report using the seminars or complete a survey, it was classified as having “limited interest.” If a program made no attempt to participate in the project despite repeated invitations, it was classified as having “no interest.”

Faculty and residents were surveyed after viewing the recorded seminars. The surveys were developed through consultation with experts in survey design and based on previously published research. Participants were e-mailed the surveys through SurveyMonkey, an online distribution software. To encourage candid feedback, e-mail addresses were not linked with individual responses. Perceptions regarding recorded seminars, reading materials, technology, and postseminar discussions were measured on a 7-point Likert scale (1, strongly disagree; 7, strongly agree).

Results

Interest

Just over half (n = 33, 52%) of the 63 US graduate orthodontic programs fully participated in this project. Ten (16%) registered for participation but did not use the teaching materials, and 20 (32%) never responded to repeated e-mail and telephone invitations to participate.

Of the 256 residents and 42 faculty who participated, 80% of the residents and 83% of the faculty completed the surveys that provided feedback on their experiences. Participants included first-, second-, and third-year residents, with 39% in their second year; 80% were required by faculty to view selected seminars. A majority (55%) of the residents were in programs lasting 33 months or more. The Fisher exact test showed no relationship between the length of the program and the level of participation ( P = 0.55).

Selection and use of recorded interactive seminars

The distant faculty were free to use any or all of the recorded seminars with their residents. Twenty-nine percent of program faculty required the residents to view all components of the Growth and Development sequence, and 23% required viewing of the Sequelae of Treatment sequence. Most programs did not require residents to watch all components of any sequence. Residents reported that they most frequently watched seminars about Growth and Development (83%) and Biomechanics (39%).

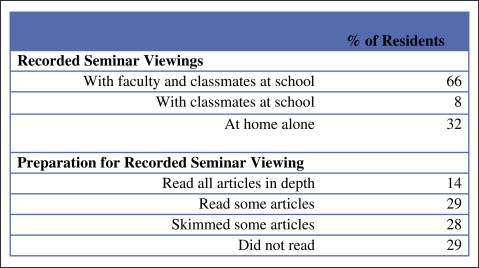

Although it was strongly suggested that they should use the teaching materials as described above, they could be used as the distant faculty wished, and the suggested protocol often was not followed. Most residents (66%) reported watching the recorded seminars with their classmates and professor during the day. Many residents (29%) reported not reading any articles before watching the recorded seminar; only 14% read all articles in depth ( Fig 1 ).

Postseminar discussions

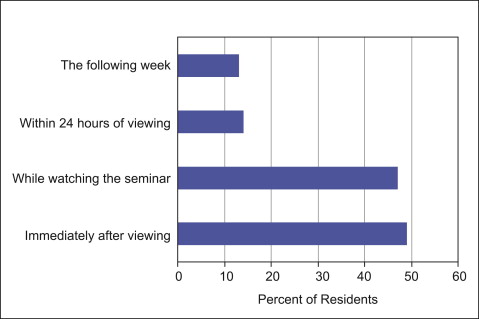

The majority of residents (73%) participated in postseminar discussions with faculty regarding the content in the recorded seminars viewed online. Seminar-related discussions were led by either faculty members from participating programs, the author of the seminar (William Proffit, Henry Fields, and others), or a combination of both. Eighty percent of the residents participated in a live discussion about the content of the seminars with their own faculty member. An equal number of residents had postseminar discussions led by the author of the seminar (9%) or participated in a combination of discussions led by the author of the seminar and their own faculty member (9%). The timing of these discussions varied ( Fig 2 ).

Perceptions

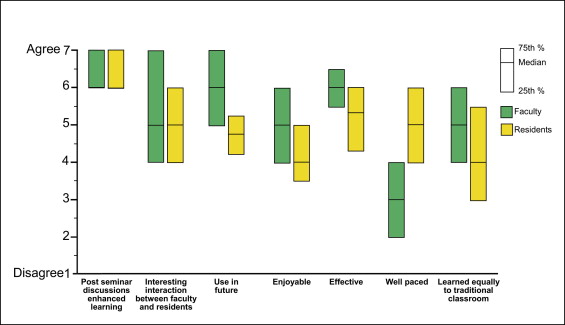

Faculty and resident perceptions of the learning experience are graphically represented in Figure 3 . Both residents and faculty were generally positive. However, faculty rated the experience on average as more enjoyable and effective than did the residents. The faculty also were more positive about using the materials again in the future. More faculty than residents thought the recorded seminars were too slowly paced. Both were close to neutral about whether residents could learn the materials from the recorded interactive seminars as well as they do in a traditional classroom. Forty-seven percent of faculty strongly agreed that the seminar content was appropriate for residents. The majority of faculty (56%) agreed that using distance learning would lessen their teaching burden. The postseminar discussions were rated highly positive by both faculty and residents.

Perceptions of the technology as rated are shown in Figure 4 . Residents strongly agreed that they were not distracted from learning because of the technology. Both faculty and residents agreed that the video clarity was acceptable, but the faculty were less positive about the sound quality. Both groups strongly agreed that having the capability to stop, rewind, and skip sections of the seminar was beneficial to the learning experience, and also strongly agreed that more extensive visual aids to supplement the discussion between the seminar leader and the live participants would be beneficial.

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses